Vol. 25, No. 1

Executive summary

The school reform debate in Wisconsin too often ignores the group most crucial to raising education outcomes in this state: teachers. Teachers are the professionals on the front line educating Wisconsin students. Yet traditional public school teacher compensation policies do not reflect that teaching is a professional career. The lock-step pay schedule used in most school districts considers only two factors to determine teacher pay: formal education and years on the job.

Merit-pay programs implemented in the United States have attempted to reform teacher compensation by giving teachers raises and bonuses tied to student performance. Such efforts have produced inconsistent results. This report recognizes the uneven results of teacher merit-pay programs, attributing their unevenness to the fact that teachers are motivated more by collaboration and student achievement and less by peer competition.

This study lays out a methodology to meet the dual goals of collaboration and competition.

The report also recognizes that the school building level is the most important unit of focus in education reform. A poor teacher in grade 10 for example, can quickly undo the work of a quality teacher in grade 9. Creating quality graduates demands consistently high-quality teaching throughout a school. Hence, the proposal in this study will incentivize the creation of quality school cultures that maximize the value of teachers rather than reward single success stories. It does this through three simple steps:

- Every five years, school leaders will choose a set of objective, measurable indicators by which their school will be judged.

- Schools that meet their targets will receive an additional $1,000 per enrolled student.

- The principal of the school will have significant flexibility on how to spend the additional money to reward and motivate teachers. For example, the funds could be used for teacher development or to provide differential pay to recognize the value or productivity of individual teachers.

Funding for the program would be available from a new categorical aid funded from future government revenues, and from private or philanthropic sources that seek to support successful schools.

A thorough review of teacher compensation in Wisconsin, the values held by Wisconsin teachers and citizens, and existing research on human capital management precedes the formal proposal. The review establishes context as to why Wisconsin teachers are paid the way they are and why the proposed reform is necessary, possible, and likely to positively impact student achievement in Wisconsin.

The shortcomings of Wisconsin’s education system cannot and should not be placed solely at the feet of teachers. The reform proposal that follows recognizes the value teachers bring to this state and seeks to give these professionals the tools and motivations needed to successfully educate the diverse body of Wisconsin’s K-12 students.

Introduction

The method by which Wisconsin pays teachers is out of date. It does not reflect the values of Wisconsin citizens, the factors that motivate teachers, or the diversity of Wisconsin students. This paper presents the case for the overhaul of the teacher compensation system used in most school districts. Further, the paper presents an example of an alternative to the current compensation system, one that provides financial rewards to high-achieving schools for the purposes of rewarding and motivating teachers.

There are plenty of good schools in Wisconsin, and there are plenty of struggling ones. Many Wisconsin students graduate prepared for productive lives; many Wisconsin students never make it to grade 12. Many parents are highly engaged in their children’s education; many are not. It follows that Wisconsin must have some excellent teachers and some that are subpar. Yet the compensation system used in most schools ignores differences between schools and differences between individual teachers.

Most school districts use a lock-step pay schedule to determine salaries for individual teachers. Under such a system, teachers are compensated not as members of a highly skilled, knowledge profession, but rather as cogs in an assembly line that possess the identical skill of delivering an identical commodity called “education” to Wisconsin students. The current pay schedule has nothing to do with actual performance and therefore misses the opportunity for principals to use compensation to influence student achievement.

Wisconsin citizens are engaged and passionate about K-12 public education. Polling done by the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute shows that Wisconsinites are more likely than the American public to pay attention to policy debates on education reform. Wisconsinites are also more likely to take a position on the worth of specific education reforms.1 Polling reveals that Wisconsin citizens support paying teachers in a manner that rewards high student achievement.

Public support for performance pay, however, has largely not translated into action. Most Wisconsin school districts continue to base teacher compensation not on performance but on time on the job and advanced credits earned. This system is different from not only what is used in the private sector but also what is used in other public-sector professions.

Economist Michael Podgursky and education professor Matthew Springer find that, compared with pay in public education, “even government civil services schedules are more flexible and market-based.”2

The rigidity of the lock-step pay schedule is less problematic for what it rewards than for what it leaves out. While experience and education credits earned are important inputs, they are only important to the extent that they contribute to the output of teacher effectiveness. Simply, there is more to a good teacher than credentials and longevity. Social skills, compassion, knowledge of the subject matter, ability to collaborate, and the ability to raise student achievement are all important.

But how should these things be measured? The problem of measurement has led to two common approaches to merit pay for teachers:

- Systems tied to standardized test scores

- Complex systems reliant on standardized test scores, classroom observations, peer review, and other soft measures

The few merit pay programs that have been implemented using the two listed approaches have produced uneven results.3 The results are predictable given the false assumptions on which uniform statewide or districtwide compensation reforms are based. First, schools are not all the same; they are unique organizations with diverse cultures. A compensation reform that raises achievement in one school should not be expected to work in all schools. Second, a good teacher can be successful for any number of reasons, many of which are difficult to quantify; research by economist Eric Hanushek finds no common teacher characteristics or teaching behaviors that consistently yield achievement gains.4

The framework presented in this report recognizes that individual teachers can be successful for any number of reasons, and more importantly that the quality of the school as a unit takes priority over the success of individual teachers. Hence, this paper argues that any meaningful reform of teacher compensation should have two key characteristics:

- It should provide substantial resources for teachers in schools that are most effective in improving student performance.

- It should give school leaders full discretion in how to use said resources to reward and motivate teachers.

Polling shows that Wisconsin residents want quality teachers and are willing to put forth the resources to get them. The values of Wisconsin citizens and teachers should be considered alongside existing research on teacher compensation and teacher motivation to develop a new, flexible model of teacher compensation that both encourages and rewards quality teaching.

This new, flexible model would tie a portion of school funding to school performance through the creation of a fund that provides substantial resources to reward and motivate teachers in schools that meet a set of measurable objectives based on the goals of their schools.

What Do Wisconsin Citizens Value in Teachers, and What Do Teachers Value?

All of Wisconsin has a personal stake in the teaching profession. Parents, taxpayers, and employers all experience the financial and social repercussions of public K-12 education. Data from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction show that in the 2010-’11 school year, 77,975 Wisconsin public school teachers earned a combined $6.2 billion in total compensation (see Table 1). It is a reasonable expectation that the wishes of taxpayers be considered when determining how this public investment is distributed.

Table 1 — Public Investment in Wisconsin Public School Teachers — 20105

Number of Public School Teachers | 77,975 |

| Average Salary Per Teacher | $52,130 |

| Total Spent on Salaries | $4,064,851,558 |

| Average Fringe Benefits Per Teacher | $26,688 |

| Total Spent on Fringe Benefits | $2,081,009,976 |

| Total Spent on Public School Teacher Compensation | $6,145,861,534 |

Note: Because of the rounding, multiplying the number of public school teachers by average salary and average benefits listed will not produce the totals listed.

Polling done by WPRI in 2008 and2010 provides insight into what Wisconsin citizens value in their teachers. First and foremost, the 2008 survey found, Wisconsin residents overwhelmingly believe the state needs to raise teacher salaries to attract more talent. Seventy-two percent of poll respondents supported raising salaries while only 23% opposed it.6 In addition, the majority favoring higher salaries held across ideology; Republicans, Democrats, conservatives and liberals all favor raising salaries. Wisconsin residents want effective teachers, and they seem willing to pay for them.

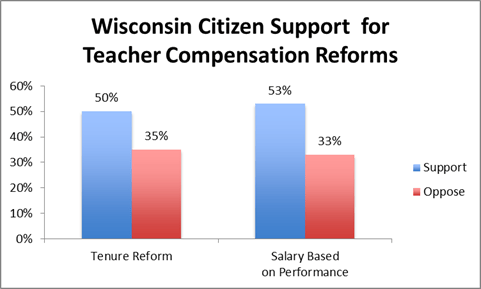

However, major elements of the current compensation system get low marks from the public. The 2010 Refocus Wisconsin polling data demonstrated that citizens believe in treating K-12 teacher compensation in a manner similar to other professions. Fifty-three percent of survey respondents say they support “basing a teacher’s salary, in part, on his or her students’ academic progress” while only 33 percent oppose it (See Figure 1). A similar percentage support reforming tenure by basing it in part on student performance.

Figure 17

The low support for tenure suggests a demand for accountability consistent with support for merit-based compensation. It would appear that Wisconsinites do not think a teacher should be able to remain a teacher regardless of performance.

Many individual teachers also find fault with the current dominant teacher compensation system. One 28-year-old teacher working under a merit pay system in a non-unionized Milwaukee charter school surveyed for this report stated:

“We give our students incentives, so why shouldn’t teachers have that dangling carrot?

Small businesses and Wall Street have merit through bonuses, so why can’t teachers? [Merit-pay] truly makes me work a little bit harder…”

When asked, “Do you favor tenure?” this teacher was even more direct:

“NO!!… Why should teachers earn tenure after only three years? …All workers should have performance standards.”

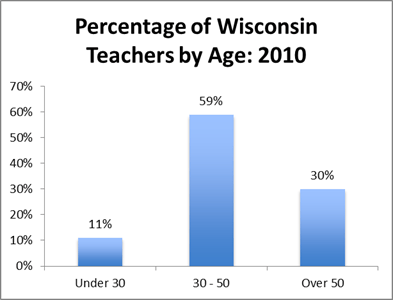

Recent events in Milwaukee illustrate why young teachers like the one quoted above might oppose tenure. In the summer of 2011, 354 Milwaukee Public School teachers received layoff notices. As required by the union contract, those most recently hired for their positions were the first to receive layoff notices.8 The seniority system has the effect of creating an unstable environment for new teachers; the message to young public school teachers is that skills, ambition, and effectiveness will not enhance job stability. Professional stability only comes from the one thing a laid-off teacher does not have: experience. Not surprising, a comparatively low percentage of public school teachers are under the age of 30 (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Wisconsin Teachers by Age: 2010

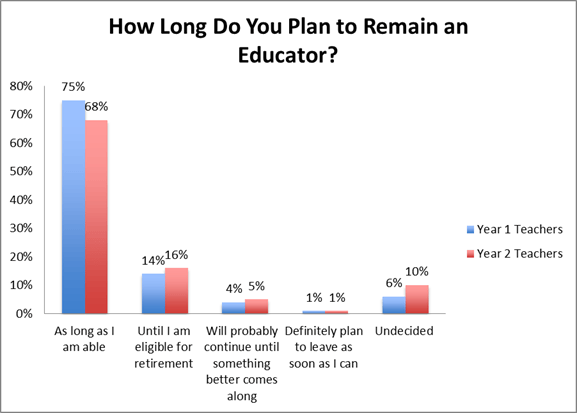

New Wisconsin public school teachers are eager to stay in the profession. Data from the Department of Public Instruction’s Wisconsin Quality Educator Initiative highlights the enthusiasm young teachers bring to the profession.910 DPI’s survey of first- and second-year teachers throughout the state shows that the vast majority want to remain teachers for the near and distant future.

As seen in Figure 3, 75% of young teachers surveyed indicate plans to stay in the teaching profession “as long as I am able.” Perhaps more telling, only 5% said they either planned to leave immediately or switch when something better comes along. The desire to remain in the teaching profession is in contrast to the career-hopping typical among many professions. A longitudinal study by the National Center for Education Statistics tracking the career status of college graduates from the class of 1993 found that by 2003, 35% of respondents who consider their job a career had at least one other career in the past 10 years.11 Just over 10% report never having a job they consider a career.

Figure 3

The desire for career stability is consistent with the commitment college students make in order to enter the profession. A Wisconsin student wishing to be a teacher must take and pass a pre-professional skills test (the PRAXIS), complete a core curriculum, complete coursework in their specialization, and finally student-teach in a classroom as a pre-requisite to state licensure. The exposure to the profession prior to licensure suggests that young teachers possess a level of awareness of the realities of being a teacher, including the salaries, prior to committing to the profession.

A review of teachers’ and citizens’ attitudes on education indicates that teachers are dedicated to their field, and that citizens want both accountability and the ability to reward excellence. These conclusions combined with the size of the investment in education illustrate the need for a new approach to teacher compensation that enables dedicated teachers to thrive, appeals to younger teachers, and gives principals tools to hold all teachers accountable for performance.

The Current State of Teacher Compensation in Wisconsin

Wisconsin teachers are primarily paid via a lock-step pay schedule that rewards two things: years on the job and credits earned beyond a baccalaureate. An example of the system used throughout Wisconsin is shown in Figure 4. A new teacher with a bachelor’s degree begins at $35,729 dollars a year, step one on the schedule. Each successive year of experience results in vertical movement of one step. A teacher in his or her 13th year, for example, would receive a salary of $53,930.

Figure 4 – Milwaukee Pay Schedule

Horizontal movement across the schedule is dependent on credits earned; 16 graduate credits, for example, would result in a first-year teacher making $37,391 compared with $35,729 for a first-year teacher with just a bachelor’s degree. When unions negotiate raises for their teachers, they are actually referring to increases in the salary amounts listed on the schedule. In addition to the across-the-board increases, teachers receive an annual raise based on an extra year of experience.

For example, the 2007-’09 MTEA contract raised MPS teacher salaries at each step by 2.5%. A first-year teacher in spring of 2007 with a bachelor’s degree, for example, was paid $34,008. A first-year teacher in the fall of 2007 received a salary 2.5% higher: $34,858. However, someone who was a first-year teacher in the spring of 2007 would also move up to step 2 (based on a year of experience) on the pay schedule in the fall of 2008 and be paid $36,404, an increase of 7%.

The roots of the lock-step schedule used in Wisconsin can be traced back some 90 years. Denver and Des Moines were the first large cities to adopt the schedule in 1921, and by 1950 it was used in 97% of American schools.13 Prior to that, teacher salaries were determined by school boards on a case-by-case basis.

The widespread adoption of this method of teacher compensation is the result of a 1944 endorsement by the National Education Association. The NEA was and is the country’s largest and most powerful teachers union. The organization endorsed the lock-step schedule in a report reviewing teacher compensation systems in 59 cities, concluding that it was a preferable alternative to an incentive system that allowed no clear way to ensure that teachers are getting what they deserve.14 The NEA was making the same criticism that opponents of teacher compensation reform make today: There is no agreement on the appropriate way to measure teacher effectiveness.

Both the lock-step schedule and the logic behind NEA’s 1944 endorsement of it are products of an era where the field of employee compensation was underdeveloped and tools for objectively measuring student achievement were lacking. These shortcomings no longer exist. Standardized testing for all K-12 students is federally mandated, and there are examples in both the private and public sector of improved ways to determine employee compensation.

Unlike much of the private and public sector, teacher compensation is not determined by productivity. Logically, a teacher who can teach larger classes, take on a larger course load, raise achievement levels of the most difficult students, improve the performance of peers through collaboration, teach more difficult subjects, or score higher on peer and principal evaluations is worth more to a school than a teacher who does none of these things. The lock-step pay schedule, however, does not allow for compensation to be aligned with relative value.

The lock-step pay schedule also assumes there is a single labor market for teachers. This is not the case. The various grades and subjects taught in school create numerous unique labor markets for different types of teachers. Demand for math teachers, for example, is far different from the demand for art teachers. In a world where ambitious, productive professionals can earn extra compensation, the lock-step pay schedule for teachers sets price ceilings for those in demand, and price floors for those who might be easier to find. The result is that some teachers are overpaid and some are underpaid based on their market and productivity.

As problematic is the existence of tenure or tenure-like systems that compensate poor teachers who are failing by any objective measure in an identical fashion to those who are excelling. Both tenure and the lock-step schedule hinder the attraction and development of talented teachers. The system is structurally designed to “satisfice.”

The term satisfice was, ironically, coined in 1956 by a former Milwaukee Public Schools student, political scientist Herbert Simon. It describes the tendency of people to make decisions that are comfortable enough to discourage a different decision, but still not optimal.15 Applied to the lock-step pay schedule, the promise of steadily increasing compensation tied to longevity encourages good and bad teachers to stay in the system. At the same time, the fact that all performance above the minimal threshold of job retention results in the exact same set of tangible benefits discourages teachers from reaching their full potential.

Research on teacher motivation suggests that factors beyond salary and bonuses should be included in an effective compensation system. Research by UW-Madison professor Allan Odden finds that collaboration and raising student achievement are primary motivating factors for teachers. It follows that teachers stuck in poorly performing schools are often lacking in motivation due to the low-performance levels of students entering their classrooms. A teacher in a low-performing school surrounded by low-quality and/or disheartened teachers who make just enough money to not leave the profession is unlikely to have constructive collaborations with other teachers. Similarly, the positive impact of collaboration with colleagues is only as good as the quality of the collaboration.

This is not the fault of individual teachers; it is the fault of a system specifically designed to discourage skill maximization. It is also part of the reason building a successful school culture is so difficult. A leader with little control over staffing and few tools for motivating staff is unlikely to build a successful school.

Monetary compensation is but one element that affects teacher job satisfaction. Incentives for encouraging teacher satisfaction and productivity must also include logistic supports such as making classroom materials readily available, proper placements, formal evaluation by supervisors, and opportunities for professional development and collaboration. Only when principals are empowered to give teachers the tools they need to be successful can the full potential of a modern compensation system be reached.

Newspaper stories of teachers reaching deep into their pockets for basic school supplies must become a thing of the past.16 Under a modern teacher compensation system, an effective teacher need not also be a martyr, just a good teacher. This can be accomplished in part by tearing down the formal barrier between teachers and school management. The pages and pages of work rules typical of Wisconsin teacher union contracts are not conducive to building an atmosphere of respect and collaboration between teachers and principals.

The issuance of layoff notices to teachers throughout Wisconsin has highlighted a significant fault line dividing the profession: age.17 A compensation system built to reward longevity has predictably created stark differences between teachers with longevity and those without it. As illustrated in Table 2, Wisconsin teachers 30 and younger make 55% less in salary and 51% less in total compensation than those 50 and over.

Table 2 – Wisconsin Teacher Compensation by Age: 2010

| 30 and under | 50 and over | |

| Average Salary | $37,688 | $58,426 |

| Average Fringe Benefits | $20,175 | $28,831 |

| Average Total Compensation | $57,863 | $87,257 |

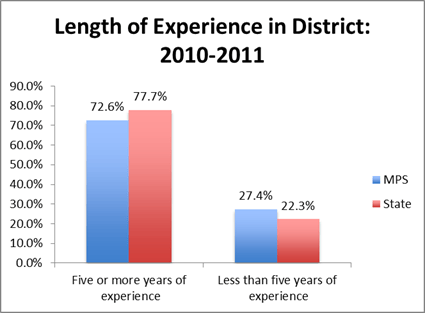

The age divide in the teaching profession is particularly important in MPS, where teachers are slightly less experienced than in the average Wisconsin district. In recent years MPS’s teaching corps has become less experienced, dropping from a high point of 80.1% of teachers having at least five years with the district in 2008 to 72.6% in 2011 (See Figure 6).18 The percentage reduction is attributable to the loss of 972 teachers with more than five years of experience and a slight increase (162) in teachers with less than five years of experience. The introduction of alternative teacher programs geared toward recent college graduates such as Teach for America has also meant an infusion of young teachers in MPS.

A recent vote on union concessions however suggests that changing teacher demographics in MPS has not yet translated to aggregate change in teacher positions on last-hired, first-fired staffing policies. Earlier this year, MPS Superintendent Gregory Thornton asked the MTEA to take concessions to reduce the number of layoffs in 2011 by 200.19 The layoffs, as stipulated in the MTEA contract, were determined by the seniority system and ensured that younger teachers would bear the burden of rejecting concessions. The MTEA conducted an internal poll that was cited as the rationale for the eventual rejection of concessions in favor of layoffs. Just over half of MPS teachers voted for layoffs.

The consequence of this lack of influence is highlighted anecdotally in a 2010 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel story on the perils of being a new teacher: It is difficult to keep a job, and even more difficult to keep a placement that puts a teacher in position to succeed. Reporter Erin Richards profiled several young teachers laid off from MPS.20 One 29-year-old teacher was eventually recalled but was moved to a different school in a different part of town to teach a different grade level. Another, a 24-year-old, changed careers rather than face the uncertainty of being recalled and placed. What is not known is the quality of either of these profiled teachers, or their value to their former schools. That is precisely the problem. Decisions to lay off and move these teachers were made without considering their value and potential.

Figure 5

Situations like these occur everywhere districts face staffing decisions. While districts like Beloit, Racine, La Crosse, and Madison avoided teacher layoffs in 2011, they were only able to do so because of retirements and resignations.21 Even if young teachers are not losing their jobs they are being moved around the district to fill vacancies caused by retirements and resignations. Such mobility makes it difficult for schools to build the “collegial work environments” so important to raising schoolwide performance.22

Say for example a principal has a strong, young math teacher who is critical to fulfilling that school’s mission. Now say the principal gets a letter from the district indicating that the school’s budget can support one fewer math teacher next year. Research in the field of Public Administration guides the manager to budget for performance and align inputs (available teachers) to maximize outputs (academic achievement).23 The logical next step would be an evaluation of teachers and the painful but necessary decision to lay off the lowest performing math teacher and rely more on the higher performers.

The head of a school is not able to make this calculus due to the seniority-driven contract. Therefore, while ideally the principal would be held accountable for the performance of the school, it is nearly impossible to actually hold principals accountable because they are prohibited from making staffing decisions that are based on performance. The lack of power given to school leaders creates predictable results reflective of the state of Wisconsin education: stagnant achievement and an absence of accountability.

Effective professional development efforts in Wisconsin are also hampered by their lack of focus on student achievement. All Wisconsin teachers licensed since 2004 are required to have a professional development plan in order to advance their license from the initial educator to professional educator phase. According to DPI, a plan must include five components24 :

- Description of school and teaching, administrative, or pupil services situation.

- Description of goal(s) to be addressed.

- Rationale for the goal(s).

- Plan for assessing and documenting the goal(s).

- Plan to meet goal(s): objectives, activities, timeline, and collaboration.

Once a plan is put together, it is evaluated and approved by a committee that includes a peer, an administrator, and a representative from an institution of higher education. The components are permissive enough that there is no guarantee that it will deal with raising measurable indicators of student achievement. Professional development plans must only be aligned with two or more of the state teaching standards, none of which directly address student achievement.25

The creation of school-level teacher mentoring programs that establish the first few years of teaching as a training period preceding full licensure is one strategy to improve professional development in Wisconsin. Such a program can give a teacher support as well as a powerful reason to optimize performance. Polling by WPRI in 2010 shows that the majority of Wisconsin residents favor the creation of such a program, even when told it is expensive.

Prior to the passage of 2011 Act 10, the lock-step method used to pay Wisconsin teachers was subject to collective bargaining. Going forward, only teacher wages are subject to collective bargaining, leaving the salary schedule (or lack thereof) to be determined by individual school boards.26 Many districts negotiated contracts prior to the passage of Act 10 that will ensure the lock-step schedule’s survival for at least a few years. However, once the next round of negotiations occurs, there is opportunity for widespread reform.

Interestingly, the Wisconsin Education Association Council went on record in February 2011 (Prior to Act 10) as supporting compensation reform, writing in a press release:27

“WEAC acknowledges the current pay schedules are outdated as they base pay only on credits and years of teaching. The system was created this way to avoid discrimination; however, it should be modernized with a new system that links pay to the areas proven to impact and improve student learning and teaching performance.”

And:

“WEAC supports replacing the single salary schedule with career path alternatives that strive to achieve four main objectives, all structured to improve student performance:

- To attract highly talented people into the profession of teaching

- To retain talented educators

- To improve the teaching skills and knowledge of the state’s teachers

- To add to the collective body of knowledge about effective teaching practices.”

The ideas presented in the press release led to the formation of the Wisconsin Framework for Educator Effectiveness Design Team, collaboration between WEAC, DPI, and several other Wisconsin education organizations. The team’s preliminary framework for a new method of teacher evaluation was released in November 2011. The strength of the proposal is that it does call for teacher evaluations that are based in part (50%) on measures of student achievement, including some school-level data. However, the proposal also relies heavily on inputs in the form of a set of complex national teacher standards that take the focus off the ultimate goal of improving student outcomes. Nonetheless, the use of achievement data when evaluating school and teacher performance is a step in the right direction.

Wisconsin is also in the process of developing a new pupil testing system for statewide use. Replacing the antiquated WKCE (Wisconsin Knowledge Concepts Evaluation) testing system presents an opportunity to acquire richer and more complete feedback on student performance. This student data is an important element in a performance-driven teacher compensation system. Further, districts throughout the state are beginning to use value-added data that assess student growth rather than presenting a snapshot of student performance. In short, Wisconsin is on the verge of having much more sophisticated tools to measure student and teacher performance.

Also currently lacking in Wisconsin are data systems that track the performance of students after they graduate from grade school or high school. Ideally, students should be tracked as long as possible and schools should be held accountable for the success of their graduates.

Coupling a new compensation system with a student evaluation system that gives principals the data they need to evaluate teacher performance — and gives policymakers data to evaluate school performance — makes the implementation of a modern teacher compensation system timely.

However, the reform proposed in this paper is not dependent on a better testing system in Wisconsin. There is nothing preventing a principal from using evaluation tools such as diagnostic testing even if they are not required; such tests are already in widespread use in Wisconsin public schools at the discretion of school and district leaders. A 2009 survey by economists Mark Schug and M. Scott Niederjohn showed that 68% of Wisconsin districts use testing beyond the required WKCE.28

More important than the statutory changes and technological advances that make a modern compensation system logistically possible are the academic realities that make a modern compensation system necessary.

The academic achievement level of Wisconsin students as indicated by the National Assessment of Education Progress has been stagnant in recent years. The NAEP, unlike the WKCE, compares Wisconsin student achievement levels to students across the country. While Wisconsin scores average to above average in math and reading overall, the performance of minority students is at or near the bottom nationally.2930 The large achievement gaps between white and non-white pupils on the ACT and the WKCE similarly indicate that Wisconsin public schools are systemically failing to prepare whole demographic groups for future success.

Finally, the aging of Wisconsin’s teaching force necessitates a compensation system that attracts and retains young teachers. Only 11% of Wisconsin public school teachers are under the age of 30, compared with 30% over the age of 50. Data from the Wisconsin Retirement System show that teacher retirements doubled in 2011 as well (4,935 compared to 2,527 in 2010).31 Wisconsin needs to beef up its young teaching corps to replace the large number of retirees and baby boomers approaching retirement age. The proposed reform is designed to attract top college students to the teaching profession.

Logic of a New Compensation System

Under collective bargaining, attempts to reform teacher compensation systems are relatively rare. However, some districts and states have experimented with systems that compensate teachers in part outside of the lock-step schedule. Economist Michael J. Podgursky and education professor Matthew G. Springer give a thorough review of the limited attempts that have been made.32

In Denver for example, a program developed by the Denver Public Schools and the Denver teachers union gives teachers annual bonuses of up to $3,000 in exchange for increases in student performance. Participating teachers create two student growth goals at the start of the year. The goals must be based on measurable baseline data and must be measured against said baseline. If both goals are met, the teacher receives a permanent salary increase worth 1% of his or her current pay. If only one goal is met, the teacher receives a one-time bonus worth 1% of his or her current pay.

In Texas, the state sets aside $10 million for distribution to 100 high-poverty, high-performing schools. Schools that qualify must use 75% of the funds received on teacher bonuses. If a school receives $100,000 for example, $75,000 must be given to teachers as bonuses and $25,000 can be used for other purposes.

Florida has had a law requiring performance pay for teachers since 2002; its most recent iteration is called E-Comp. E-Comp bases a teacher’s salary in part on the academic performance of his or her students, and it provides a bonus to teachers worth up to 5% of their salary if their students are among the top achievers statewide on the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test.33 School districts are given flexibility to determine how student achievement is measured for the portion of performance pay that is used to determine salary.

All three of these systems have positive attributes; a reformed compensation system must be tied to achievement and must include flexibility. However, none of these offers the comprehensive reform that is needed in Wisconsin.

Defining Resources

Defining what constitutes a resource for a school is challenging. A resource from the point of view of a principal goes beyond money and includes teachers, facilities, and assessment strategies. While schools need some level of funding to cover fixed costs, increasing the financial resources available to schools does not ensure improved outcomes. The body of existing research concludes that spending is not correlated to achievement.34 University of Arkansas professor Jay Greene deems the belief that money is related to substantive improvement in student achievement “the money myth.” Greene points to research by Stanford economist Eric Hanushek finding that only 27 of the 163 methodologically sound studies on the connection between spending and achievement indicate a positive relationship.

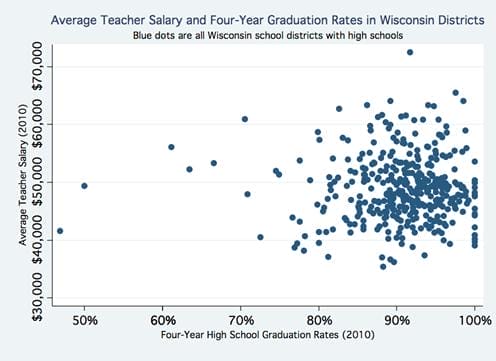

Figure 6 looks specifically at Wisconsin, plotting average teacher salaries (the largest component of school spending) in 2010 against graduation rates in all Wisconsin school districts with high schools. There is no evidence of any correlation between what a school district pays its teachers and the percentage of pupils who graduate. There are many low-spending districts that achieve above-average results. One example, New Lisbon, has a four-year graduation rate of 96% and an average teacher salary lower than 90% of the districts in the state. Meanwhile Racine graduates just 67% of its high school pupils in four years despite having an average teacher salary higher than 75% of districts in the state. Given that student performance is not considered when determining teacher pay in Wisconsin, the absence of a clear pattern in Figure 6 is not surprising.

The 2009 experience with the federal Race to the Top funding illustrates how financial carrots can alter the landscape of teacher compensation in Wisconsin. In an attempt to garner federal funds, the Wisconsin Legislature passed and Gov. Jim Doyle signed into law legislation removing Wisconsin’s longstanding prohibition of using standardized test scores to evaluate teachers. The law change did not result in Wisconsin getting a piece of the $4 billion plus distributed to states, but it did demonstrate the willingness of even the staunchest advocates for the status quo to reverse positions on teacher compensation in return for resources. There is no reason the same logic of rewarding change with resources cannot be deployed to reform longstanding teacher compensation methods.

Figure 6

School as the Unit of Focus

In most districts, all of the teachers are covered under the same contract, i.e., the same compensation system. This is a historical quirk, one that runs counter to what recent research would suggest; compensation should be based on the performance of individual schools within the district. A one-size-fits-all, districtwide compensation system has outlived its usefulness.

Take for example MPS. Under No Child Left Behind, the district is considered to be failing. Yet MPS boasts of having the highest-performing high school in Wisconsin, Rufus King.35 King is unique in that it has a selective admissions process, but there are also non-selective schools in MPS that are working. IFF, a Chicago based non-profit that donates to several Milwaukee schools, found in a 2010 analysis that 10.9% of public school students in Milwaukee are enrolled in 23 non-selective public schools that are meeting state standards.36

The unit of analysis necessary to maximize the impact of teacher compensation reform is the school. While quality teachers deserve to be rewarded even in failing schools, doing so will not lead to permanent academic gains. A student remains in a school for multiple years and is taught by multiple teachers; the work of an outstanding teacher can quickly be undone by the work of a poor one. A comprehensive compensation reform accepts this reality and provides tools for school leaders to build successful school staffs and incentives for quality teachers to flock to effective school leaders.

Focusing on the school is not meant to minimize the individual performance of outstanding teachers in struggling schools, but rather to recognize that students need a consistently high level of teacher performance to prosper academically. The key to creating a consistently high level of teacher performance is building a school culture that demands it. Education professors Kent Peterson and Terrence E. Deal summarize the importance of school culture thusly:37

“[A] positive school culture improves school effectiveness and productivity. Teachers and students are more likely to succeed in a culture that fosters hard work, commitment to valued ends, attention to problem solving, and a focus on learning for all students. In schools with negative or despondent cultures, staff have either fragmented purposes or none at all, feel no sense of commitment to the mission of the school, and have little motivation to improve.”

Building such a culture demands a strong school leader. UW-Madison professor Allen Odden concludes that teachers need to be strategically managed to build a culture of success.38 A far-reaching 2010 study of Chicago public schools concluded much the same thing: “Schools with strong school leadership were seven times more likely to improve in math and nearly four times more likely to improve in reading than schools weak on this measure.”39

The need for strong managers in public organizations is not a new concept. It was in 1937 that public administration experts Luther Gulick and Tyndall Urwich penned the acronym POSDCORB to describe the work of a chief executive.40 POSDCORB stands for:

- Planning

- Organizing

- Staffing

- Directing

- Coordinating

- Reporting

- Budgeting

A principal who is given authority to do these things can and should be held accountable for results. Efforts in the late 1990s to give MPS principals more autonomy did not spur lasting achievement gains because they were far too limited to allow for strategic management of resources.41 Take the earlier example of the MPS teacher laid off after being hired by a school. Giving principals the autonomy to hire staff is pointless if the new hire is arbitrarily moved a year later. Union contracts and tenure constrict MPS principals as they execute their tasks as executives. It is illogical to fault these principals for failing to raise achievement when they lack the tools to do so.

However, there are also indications that school leaders lack more than the tools to raise student achievement. Like teachers, a Wisconsin principal need not show a track record of raising achievement prior to obtaining a position. The prerequisites for an administrator license are completion of a higher-education program plus three consecutive years and 540 hours of classroom experience. Elected school boards do have power over principal appointments; ideally they would exercise a degree of quality control. However, high principal turnover in districts like MPS makes filling empty positions with quality talent difficult for even well-intentioned school boards.42 A modern teacher compensation system must consider the need to attract quality school leaders in addition to teachers.

Today, school board members, committees, the superintendent, voters via referendum, principals, teachers, aides, and others share the responsibility of POSDCORB in Wisconsin school districts. The task of management is spread thin enough that everyone has a legitimate reason why he or she cannot be held accountable for results. Consolidating responsibility and accountability at the school level is a necessary step to building a teacher compensation system that works. This concept is not new; it is the backbone of the charter school model where schools trade accountability for freedom. A modern compensation system will grant rewards to successful school leaders who give teachers the tools and motivations they need to raise academic achievement.

School leaders who raise student outcomes should be given substantial resources to reward and motivate teachers. The importance of teachers is obvious: They are the front-line employees delivering education. A specific curriculum, piece of technology, or well-equipped school is merely a tool that is useless without a quality teacher.

The concept whereby principals are given more authority over determining teacher compensation is generally referred to as a merit pay. Merit pay systems are rare and are generally viewed with skepticism by teachers. Much of the unpopularity of merit pay systems among teachers stems from the problem of measuring teacher quality. One veteran teacher surveyed for this report put it succinctly:

“I only favor merit pay if the system is a thoughtful, fair one…. I have yet to see any suggested system that appears comprehensive enough.”

The reservation expressed by that teacher is bolstered by the work of Eric Hanushek, an economist who has studied what makes successful schools. The underlying problem identified by Hanushek is that there does not exist a common set of characteristics that equate to teacher quality. He recently commented on this in an interview with Studentsfirst.org:

“For a long time, we’ve tried to find out what it is about schools that leads to higher achievement of kids and whether schools can be a good instrument in closing achievement gaps. That research has gone on now for over 40 years and my summary of it is pretty simple: Good teachers are the one resource that is important. Yet we don’t have any descriptors of what a good teacher is. While some teachers are much more effective than others, we can’t necessarily identify what it is about them — is it their experience, their training, their personality?”43

Hanushek identifies a vexing problem: Teachers are the front-line employees delivering education and obviously an important factor in determining student outcomes, yet there is very little evidence that identifiable commonalities among successful teachers exist. The inconsistent performance of a merit-pay system based at the teacher level is unsurprising given these conclusions.

Merit-pay systems that reward individual teachers with bonuses based strictly on test scores have not shown robust positive results. A comprehensive, three-year scientific study on merit pay in Nashville, called the Project on Incentives in Teaching, found that even the promise of large teacher bonuses (up to $15,000) for increased test scores failed to yield consistent student achievement gains.44 The study tracked the performance of students taught by two groups of teachers, one eligible for bonuses and one not. Little difference was found between the two groups as they affected student performance. This leads to the conclusion on the part of the evaluators that incentive pay “did not lead overall to large, lasting changes in student achievement.”

Evaluators found interesting reasons why the Nashville experiment was not successful. Surveys of teachers participating in the study showed that 80% of teachers agreed that the potential for bonuses “has not affected my work, because I was already working as effectively as I could.” This finding is in line with a conclusion that money is not the prominent factor motivating teachers.

A similar conclusion was reached by a National Center for Education Statistics survey of former public school teachers that indicated low pay is not a major reason why teachers leave the profession. More teachers cited school factors (9.8%), personal reasons (42.9%), and even contract non-renewal (5.3%) than salary and benefits (4.0%).45 For all of the consternation over teacher salaries, it seems ironic that salary and benefit levels do not drive many teachers away from the profession.

Education professors Allen Odden and Carolyn Kelley find that “helping students achieve and collaboration with colleagues on teaching and learning issues” are the primary factors motivating teachers.46 These findings as well as the Nashville results are why Odden recommends incentivizing achievement with bonuses at the school level and not the teacher level. School-level rewards can allow for collaboration among colleagues and competition between schools.

For example, without the labor market restrictions of seniority and tenure, teachers would naturally seek out schools that provide the work environments they desire. Similarly, school leaders motivated by the possibility of autonomy and resources in return for student achievement gains will seek out teachers who can deliver such gains. More importantly, giving successful schools additional resources in return for achievement gains through a per-pupil categorical aid encourages competition to enroll more pupils. While market forces may not motivate teachers to compete with each other, they do motivate schools to compete for quality teachers and successful schools to compete for additional students.

A carefully designed categorical aid distributed annually by DPI directly to schools solely on the basis of measurable achievement gains can stimulate competition and collaboration in a way that improves student achievement. To be effective such a system needs to:

- Measure success in a logical easy to understand manner

- Give principals reason to participate

- Reward and motivate teachers

The diversity of Wisconsin schools and students requires a system of rewarding teachers that accounts for the needs of the student populations and grade levels being served. The framework presented here uses test scores and other measurable variables to objectively judge performance but does so in up to three defined ways. Participating schools that meet their goals under the framework receive the categorical aid. While the model is a single approach to compensation reform, it is based on concepts that allow for limitless variation at the school level.

An accurate measurement of school success must go beyond a simple review of raw WKCE scores. While the scores are an indicator of how well students are performing on the WKCE, they do not yield information on how schools and teachers are impacting that performance. For example, a teacher may begin the year with a pupil well below average that is at grade-level by the end of the year. That teacher has made tremendous progress in that situation; however a raw test score will only show an average student.

A better measure of teacher performance is student growth scores where the specific impact of a teacher or school can be isolated and tracked over time. Equally important when evaluating teacher performance is consideration of attainment indicators such as high school graduation and future success.4748 While raising student test scores is important, it is much less important if that student does not graduate from high school. A higher achieving dropout is still a dropout. The proposed framework utilizes measurable indicators of success that are transparent to the public.

A Categorical Aid for Teachers in Successful Schools

The manner in which an organization — be it a school, government agency, small business, or large corporation — compensates its employees reflects the values of that organization. The salary levels, performance bonuses, quality of health benefits, day-to-day flexibility, and vacation time offered to employees are all forms of compensation used by employers to attract the type of person they believe will help make their organization successful. Yet public school leaders are generally restricted from using compensation as a tool to build a successful school culture. The following proposal removes this restriction by giving successful school leaders additional funds earmarked for teachers in the form of a new $1,000 per-pupil categorical aid.

Categorical aids are state education funds distributed outside of the school aid formula; they are used to fund specific initiatives such as the Student Achievement Guarantee in Education small class size program and are appropriate for this reform.49 The statewide student-teacher ratio in Wisconsin is 13.9, meaning an average classroom in a qualifying school would get $14,000 from this fund. A relatively small investment of $50 million in this program (1.17% of what is spent on education in the state equalization formula) could support teachers at 128 average-size schools serving almost 50,000 students.50

Participation in the categorical aid program would require schools to:

- Eliminate tenure and the lock-step pay schedule

- Meet a set of measurable academic goals

- Spend the $1,000 per-pupil categorical aid on teachers

Eliminating Tenure and the Lock-Step Pay Schedule

School leaders cannot be held accountable for the performance of their teachers if they cannot make hiring and firing decisions. Tenure systems (and their equivalents) limit the discretion of principals and are incompatible with this reform. The recent changes to collective bargaining in Wisconsin may very well make the need to forgo tenure in order to receive this aid a moot point; tenure is not in Wisconsin state law and will only continue at the discretion of individual school boards.

The lock-step pay schedule is also incompatible with a modern compensation system. It is not a system that recognizes results. Therefore, schools that wish to participate in the categorical aid program must forgo the lock-step schedule in favor of a compensation system based on a teacher’s relative value to the school. Other public-sector employers across Wisconsin have long used these approaches to determine employee compensation. There is no reason schools could not, too.

Theories of private-sector compensation could also be used. Instead of a formal schedule, an employer generally sets a base salary by conducting a job evaluation that considers what other private-sector employers are paying employees to fill similar positions. The employer then adjusts the base salary dependent on the relative worth of that employee to the organization based on the employee’s skills and performance.51

Local school boards play a central role in making these alternatives viable. While the categorical aid is distributed at the school level, districts must make districtwide changes or allow principals to make school-level changes to their tenure and pay systems for this reform to work.

Meeting a Set of Measurable Academic Goals

After making the necessary tenure and pay schedule reforms, a school seeking aid would enter into something similar to a charter contract. A principal must specify once every five years the set of objectives that the school will be measured against.

Below are examples of three categories from which schools could choose, as well as their goals and measurable indicators:

Category 1 — General Education Grade Schools

Goal: Prepare students for success in high school

Output indicators:

- 75% or more of pupils are scoring advanced/proficient on composite scores on the state standardized exam.

- 75% or more of pupils in the bottom 10% of the school are showing a composite score value-add above one grade level.

- 75% or more of graduates go on to graduate from high school in six years or fewer.

Category 2 — Value-Add Grade Schools

Goal: Get struggling grade school students back on track for high school success.

Output indicators:

- 75% or more of pupils in the school are showing a composite score value-add above one grade level.

- 75% or more of graduates go on to graduate from high school in six years or fewer.

Category 3 — High Schools

Goal: Prepare students for college or a technical career.

Output indicators:

- 90% or more of students graduate from high school in four years.

- 75% or more of students score above state average for their demographic group on the ACT and/or complete coursework in a technical skill that can lead to certification.

- 75% or more of students complete a professional program, technical school, join the armed forces, or obtain employment within four years of graduation, and/or graduate from a two- or four-year college within six years of graduation.

The output indicators are designed for two things: feasibility and measurability. Existing data tools should make all these indicators easily measurable. The use of easily measurable indicators ensures that the determination of school eligibility for funds is fully transparent to the public.52

Schools that make the required tenure and pay schedule reforms and meet their chosen objectives would receive the categorical aid on a per-pupil basis annually as long as they continue to meet objectives.

Spending the Per-Pupil Categorical Aid on Teachers

As mentioned, the proposed categorical aid must be spent on teachers. Substantial new funds for teacher compensation and development combined with autonomy for school leaders would significantly change the relationship between teachers and management.

First, it encourages proper placement and support of teachers. It is against the interest of a principal to put a teacher in a grade level or subject where he or she does not thrive.

Second, teachers with high-demand skills and proven track records can receive pay, supports, and flexibility far beyond anything allowed in current union contracts. Instead of being protected by work rules, teachers in these schools will be empowered by the skills and level of performance they bring to an organization.

The compensation packages teachers currently receive are capped both by the lock-step pay schedule and the lack of discretionary funds available for alternative forms of compensation such as bonuses, flexibility, release time, and professional development.

While school leaders need flexibility in distributing this money, it is a substantial amount and it must be spent on teachers. Under this reform, teachers in schools that are meeting academic goals will receive increased compensation.

The teaching profession itself can also benefit from this reform. Quality teachers will be in high demand by school leaders seeking to build organizational cultures that lead to success. It will be in the interest of schools seeking these funds (and the districts in which they reside) to make their work environments as attractive as possible to teachers. Simply tying substantial funding to the academic outcomes of schools greatly empowers those most able to impact academic outcomes: teachers.

Public and Private Funding

The money needed to pay for this program should come from a combination of private sources and public sources in the form of a new categorical aid created when increased government revenues to state government allow for growth in school aids.

Private sources of funds can be utilized through a tax-credit program where corporations receive an annual 100% tax credit for up to $500,000 donated to equalizing schools. The credit would work similar to private school tax-credit programs in Florida and Pennsylvania except the money will reward successful public schools instead of providing students a path out of unsuccessful ones.53

Donations could be made to the statewide fund or directly to an eligible school. Such an approach encourages businesses to engage directly with successful public schools in their own communities. While the tax-credit would result in a reduction in corporate tax revenues, the money would still be going directly to an essential public service.

The logistics of distributing funds to qualifying schools should be simple given the use of transparent, measurable indicators of success. Annually, DPI would send a check directly to a qualifying school.

Potential Obstacles

Visionary school leaders able to motivate their staffs to raise achievement are easier to imagine than produce. Fortunately there are organizations operating in Wisconsin tasked with creating the cadre of future leaders Wisconsin needs to make the proposed reform viable.

- Teach for America, which places high-performing college graduates in urban schools with the long-term mission of engaging them in educational leadership, had about 90 teachers in Milwaukee public, private, and charter schools last year.54

- New Leaders for New Schools, an organization founded by a Milwaukee native that trains promising young people to become principals, trained 32 leaders in Milwaukee between 2007 and 2011. While the organization recently stopped training new leaders in Milwaukee, it remains committed to supporting the young people who have been trained.55

Aside from these national organizations, there are no doubt hundreds of principals already operating in quality Wisconsin schools who can further improve their schools’ performance if given the tools to do so.

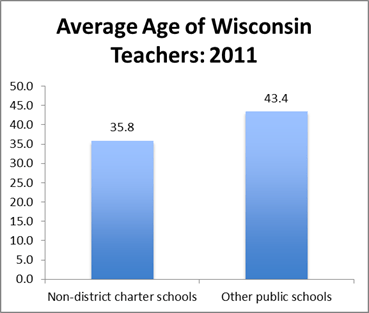

One thing that should not be a problem is finding teachers willing to forgo tenure and the lock-step pay schedule in exchange for the potential for additional pay, collaboration, and the satisfaction of teaching at a high-performing school. The example of non-union charter schools throughout Wisconsin shows that there are many Wisconsin teachers already willing to do this. Tellingly, the average age of teachers in non-district charter schools in Milwaukee is significantly lower than in other Wisconsin public schools (See Figure 7).

Figure 7

Conclusion

Wisconsin’s teacher compensation system is outdated, out-of-touch, and not designed to attract and retain top talent. Lessons from the public and private sector, advances in data systems, and the information available on teacher motivations should be the backbone of a new system that reflects the values of Wisconsin and the needs of teachers and students.

Current work in Wisconsin to create a new assessment system can be developed with the proposed framework in mind. Similarly, efforts being spearheaded by Gov. Scott Walker to create a school grading system should recognize the importance of attainment and measure success with variables that include graduation rates and future measures of success.56 If properly designed, a school grading system could complement if not supplant the presented categories for defining success.

The 2011 changes to collective bargaining make the implementation of the proposed reform possible, but the continued middling performance of Wisconsin pupils on key indicators makes the implementation of compensation reform necessary. Teachers are a school’s most valuable employees; it is time to recognize this by giving them access to substantial new resources in exchange for improving academic outcomes at the school level.

Goldstein, K. M., & Howell, W. G. (2010). Public Voices: Wisconsin’s Mind on Education. In W. Kozak (Ed.), Refocus Wisconsin (pp. 134-142). Hartland, WI: Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.

Podgursky, M., & Springer, M. G. (2007). Credentials Versus Performance: Review of the Teacher Performance Pay Research. Peabody Journal of Education, 82(4), 551-572. P. 552

Odden, A., & Kelley, C. (2002). Paying Teachers For What They Know and Do. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hanushek, E. A. (1994). Making schools work: Improving performance and controlling costs. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction 2011 PI-1202 Fall Staff Report All Staff File

WPRI. (2008). Opinions About Wisconsin Public Education Are Similar to 20 Years Ago. Thiensville, WI: Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.

Goldstein, K. M., & Howell, W. G. (2010). Public Opinion in Perspective – Wisconsin’s Mind is on Education Refocus Wisconsin. Hartland, WI: Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.

Herzog, K. (2011, June 29). Thornton reveals 519 layoffs, including 354 teachers, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

DPI. (2009). 2008-2009 Initial Educator Survey: Year 1 Teacher. Madison, WI: http://dpi.wi.gov/tepdl/pdf/iesurveytch1_09.pdf

DPI. (2009). 2008-2009 Initial Educator Survey: Year 2 Teacher. Madison, WI: http://dpi.wi.gov/tepdl/pdf/iesurveytch2_09.pdf

Choy, S. P., Bradburn, E. M., & Carroll, C. D. (2008). Ten Years After College: Comparing the Employment Experiences of 1992-93 Bachelor’s Degree Recipients With Academic and Career-Oriented Majors. Washington D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics.

2008-2009 Initial Educator Survey, DPI Wisconsin Quality Educator Initiative. Year 1 teachers n = 724, year 2 teachers n = 365

Sharpes, D.K. (1987). Incentive Pay and the Promotion of Teaching Proficiencies. Clearinghouse, 60(9), 406-408.

IBID

Simon, H. (1956). Rational Choice and the Structure of the Environment. Psychological Review, 63, 129-138.

Richards, E. (2011, August 20). Teachers, families bear burden of school supplies, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

DeFour, M., & Kittner, G. (2011, February, 24). Madison School District preparing hundreds of teacher layoff notices, Wisconsin State Journal.

Wisconsin Information Network for Successful Schools: http://www.dpi.state.wi.us/sig/.

Tanzilo, B. (2011, July 28). Teachers vote against concessions, Electronic, OnMilwaukee.com.

Richards, E. (2010, August 23). MPS layoffs a hard lesson for young teachers, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Author’s inquiry with the Beloit, La Crosse, and Racine Unified School Districts. October 12, 13, and 14 respectively.

Odden, A., & Kelley, C. (2002). Paying Teachers For What They Know and Do. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. P. 129.

Dresang, D. L., & Huddleston, M. W. (2009). The Public Administration Workbook. New York: Pearson Longman, p. 291.

http://dpi.wi.gov/tepdl/fqlpdp.html

Professional Development Plan: Initial Educator Toolkit. (2009) Wisconsin’s Quality Educator Initiative PI 34. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Wisconsin 2011 Act 10

Moving Education Forward: Bold Reforms. (2011). Madison, WI: Wisconsin Education Association Council.

M.C. Schug, & M.S. Niederjohn, M. S. (2009). “Value Added Testing: Improving State Testing and Teacher Compensation in Wisconsin.” Hartland, WI: Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.

http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/states/

Hetzner, A. (2010, March 24). “State’s black fourth-graders post worst reading scores in US,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

“Wisconsin Teacher Retirements Double in Wake of New Law.” (Aug. 31, 2011). The Associated Press.

Podgursky, M. J., & Springer, M. G. (2007). “Teacher Performance Pay: A Review.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 26(4), 909-949.

Florida Department of Education, Educator Recruitment and Professional Development Frequently Asked Questions: http://www.fldoe.org/faq/default.asp?Dept=131&ID=765#Q765

Hanushek, E. (1997). Assessing the effects of school resources on student performance: An update. Educational evaluation and policy analysis, 19(2), 141. And Greene, J., Forster, G., & Winters, M. Education myths: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

WTAQ. (2010). Newsweek: Rufus King Ranked WI’s Top Public High School. WTAQ. Retrieved from http://wtaq.com/news/articles/2010/jun/14/newsweek-rufus-king-ranked-wis-top-public-high-sch/

IFF. (2010). Choosing Performance: An Analysis of School Location and Performance in Milwaukee. Chicago, IL.

Peterson, K. D., & Deal, T. E. (2009). The Shaping School Culture Fieldbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. P. 11.

A.R. Odden, (2011). “Strategic Management of Human Capital in Education.” New York: Routledge.

Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., & Luppescu, S. (2010). Findings from Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Retrieved from https://blogs.uchicago.edu/uei/applied_research/findings_from_organizing_schoo.shtml

Dresang, D. L., & Huddleston, M. W. (2009). The Public Administration Workbook. New York: Pearson Longman, p. 67.

Gardner, J. (2002). How School Choice Helps the Milwaukee Public Schools. In A. E. R. Council (Ed.). Milwaukee, WI.

Hessel, K. (2011, July 5). MPS getting 39 principals as retirements soar, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

studentsfirst.org. (2011). Why an effective teacher matters: A Q & A with Eric Hanushek. Retrieved from http://www.studentsfirst.org/blog/entry/why-an-effective-teacher-matters-a-q-a-with-eric-hanushek#

Springer, M. G., Ballou, D., Hamilton, L., Le, V.-N., Lockwood, J. R., McCaffrey, D. F., . . . Stecher, B. M. (2010). Teacher Pay for Performance: Experimental Evidence from the Project on Incentives in Teaching Project on Incentives in Teaching. Nashville, TN: National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt University.

Table 6 NCES Teacher and Attrition survey 08-09.

Odden, A., & Kelley, C. (2002). Paying teachers for what they know and do: New and smarter compensation strategies to improve schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. P. 81.

Witte, J., Carlson, D., Cowen, J., Fleming, D., & Wolf, P. J. (2011). MPCP Longitudinal Educational Growth Study Fourth Year Report. SCDP Milwaukee Evaluation. Fayetteville, AK: University of Arkansas.

Wolf, P. J., Gutmann, B., Puma, M., Kisida, B., Rizzo, L., Eissa, N., . . . Silverberg, M. (2010). Evaluation of the Impact of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: Final Report. In US Department of Education. Washington D.C.: Institute of Education Science.

Kava, R., & Merrifield, L. (2011). State Aid to School Districts. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

The average Wisconsin school enrolls 390 pupils.

Burgess, L. R. (1989). Compensation Administration. Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Company. P. 230.

All output indicators dependent on future success will become required as they become measurable. For example, a high school seeking to receive funds through this program cannot meet the required indicator that 75% of its students go on to graduate from college in four years until four years after its first cohort of students graduate. Schools that do not develop systems to track graduates will lose their eligibility for this aid.

Campanella, A., Glenn, M., & Perry, L. (2011). Hope for America’s Children School Choice Yearbook 2010-11. Washington D.C.: Alliance for School Choice.

Richards, E. (2010, June 10). Program scores some victories amid struggle in MPS, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

http://www.nlns.org/Locations_Milwaukee.jsp#education

Walker, S. (2011, September 25, 2011). “Schools need more than money to improve,” Wisconsin State Journal.