Preferential contracts undermine the truly disadvantaged, and programs are prone to fraud

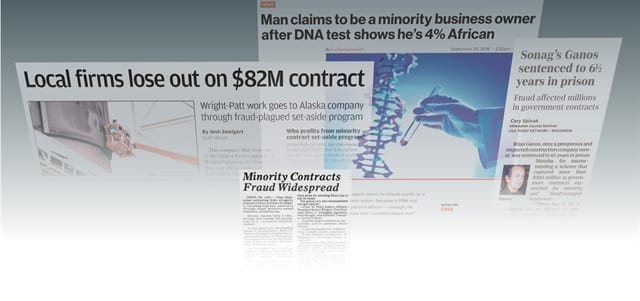

The merits of preferential set-aside programs are once again under scrutiny after the conviction last year of Brian Ganos, a successful Latino businessman in the Milwaukee area who illegally obtained more than $260 million in government contracts.

The Ganos case underscores what critics have said — and what decades of headlines about court cases across the country have proved — about the controversial federal, state and local programs: They’re often prone to fraud, which in turn hurts legitimate minority and disadvantaged business owners.

But the criticism doesn’t stop there. Some argue that the programs discriminate against minorities, drive up project costs through non-competitive bidding and can even stunt the development of smaller, disadvantaged companies.

In addition, some contracting agencies designate overly broad groups — women, for instance — as disadvantaged, even though it’s unlikely that all women are disadvantaged. As another example, the City of Chicago is considering taking set-asides a step further by designating businesses owned by gays and transgender people as disadvantaged.

Looming over all of this is the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1989 that, in effect, said set-aside programs were unconstitutional except under certain circumstances where discriminatory practices could be proven via so-called disparity tests.

But some observers doubt that municipalities and other agencies even bother to conduct such studies, which are time-consuming, expensive and prone to inherent thumb-on-the-scale bias.

“Set-aside programs tend to be cosmetic as well as almost an alliance between politically powerful and not particularly disadvantaged minorities on one hand and a guilty white liberal class on the other,” says Richard Esenberg, president of the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty.

“At the end of the day, they tend to benefit a relatively small group of favored market participants — benefits are not very diffuse,” he adds. “No one stops and asks if they really are effective.”

Case in point

Time and again over the years, headlines have chronicled concerns, questions about fraud and misrepresentation, and criminal charges and convictions. In Wisconsin alone, there have been multiple allegations — including the most recent case involving Ganos, the former owner of the now-defunct Sonag Company Inc.

The 59-year-old Muskego resident started out as a set-aside success story who legitimately used such contracts to build Sonag into a major player among local construction firms. Among other projects, the company worked on the Fiserv Forum and the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Co. office tower in downtown Milwaukee.

Over the years, Sonag also reportedly earned federal and military contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The company was so successful that it eventually graduated from the set-aside program.

But Ganos — a former chairman of the local Hispanic Chamber of Commerce who in 2005 was named a regional Hispanic businessman of the year by the United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce — apparently wasn’t ready to give up his seat on the set-aside train. Instead, he formed several shell companies with fake straw owners, thus allowing him to illegally keep benefiting from set-aside contracts.

In all, federal prosecutors estimate that Ganos netted $10 million to $15 million in profits — money that otherwise could’ve poured into the coffers of truly disadvantaged businesses.

Ganos was indicted by a federal grand jury in April 2018 on 22 counts related to fraud, conspiracy and money laundering. He pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud and another count of mail fraud in June 2019. Last December, a federal judge sentenced him to six and a half years in prison. Stephen Hurley, Ganos’ defense attorney, did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Inevitable fraud?

Set-aside programs are ripe for this kind of fraud, mainly because some verification processes allow businesses to self-certify as eligible, critics say. A good example is the federal Women-Owned Small Business (WOSB) programs.

In 2019, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that about 40% of the WOSB-certified businesses included in an audit sample were ineligible. The GAO also expressed concern about the reliability of third-party certification companies that some businesses hire.

Even worse, an audit of the program conducted in June 2018 by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), found 50 of 56 sole-source contracts — those issued without competitive bidding — did not meet the program’s criteria. (The SBA, which oversees most federal set-aside programs, has since proposed beefing up the certification process.)

In another instance, a 2019 GAO study found that 20 of 32 companies reviewed had used “opaque corporate structures” to conceal ownership and obtain set-aside contracts. The study was spurred by congressional concerns about companies that use complicated business structures to blur ownership lines when trying to obtain set-aside defense contracts.

“An inevitable byproduct (of set-aside programs) is corruption and fraud,” says Roger Clegg, general counsel for the Center for Equal Opportunity, based in Falls Church, Virginia. The conservative think tank studies issues of race and ethnicity and is devoted to opposing race-based decision-making at all levels of government.

“In programs that use racial preferences, I believe it’s very common on every level – federal, state and municipal – for companies to pretend to be black- or female-owned,” Clegg continues. “Furthermore, such programs increase project expenses because contracts aren’t awarded to the lowest bidders. For all those reasons, this kind of thing should stop.”

“The left thinks it’s racist to oppose racial preferences,” he adds, when asked if the organization ever gets accused of being racist for its opposition to set-aside programs. “It’s quite astonishing.”

Landmark court case

Set-aside programs have been controversial through the decades, uneasily rubbing elbows with the principles of equal protection under the law. That controversy culminated in 1984 when J.A. Croson Co., a plumbing firm, sued the City of Richmond, Virginia, arguing that its set-aside program was unconstitutional.

The case started innocently enough when Croson bid on a contract to provide urinals for the city jail. At the time, Richmond had an ordinance that required non-minority-owned contractors to subcontract at least 30% of a project to minority-owned businesses.

When Croson couldn’t find a suitable minority-owned subcontractor, the city threw out its bid. The company then sued. And in 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that essentially guides the structure of set-aside programs today.

Written by now-retired Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the ruling essentially said set-asides are constitutional only if they pass a “strict scrutiny” test — provide compelling proof that ongoing discrimination exists and that a set-aside program is the only remedy. That remedy must be “narrowly tailored” to cover only the specific group suffering from the discriminatory practices.

‘Sketchy’ disparity studies

To prove there’s a compelling need to use set-aside programs, government bodies that issue contracts must perform what’s called a disparity study. The Center for Equal Opportunity opposes such studies. In fact, Clegg says he does a daily internet search to find municipalities that are considering using them and then sends a form letter encouraging them to stop.

“Disparity studies sometimes can be kind of sketchy,” he says. Sometimes cities approach the companies hired to perform the studies and say they want to find disparity so they can use certain preferences to fulfill political agendas.

“So, these companies put their thumb on the scale to find disparities because that’s what their clients want,” Clegg says.

Furthermore, disparity studies — usually performed by only a handful of companies nationwide — often are hundreds of pages long and include a plethora of tables and charts, says George La Noue, an outspoken critic of set-aside programs. La Noue is a research professor of political science and of public policy in the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

“I just read one study that had 107 tables and about 13 charts,” he says. “As you can imagine, it’s extremely difficult for a typical city councilperson or state legislator to know how to analyze one of these studies. It takes a considerable amount of work to determine whether even the mathematics of the study are correct, not to mention other conclusions.”

Disparity doesn’t mean discrimination

La Noue also points out that just because a disparity exists, it doesn’t mean there’s discrimination that requires a set-aside remedy. As an example, he cites highly specialized work that perhaps only a few companies can perform. As such, awarding contracts to those companies might appear to be a disparity but wouldn’t qualify as discrimination against other businesses.

“And once a disparity is found, you have to find what causes it,” he explains. “But it’s very uncommon to identify the reason for the discrimination … the consulting firms will not go farther and identify the cause of the disparity. And without that, it’s hard to tailor a narrow remedy for it.”

La Noue also contends that many set-aside programs used nationwide aren’t narrowly tailored. But suing cities and other government agencies is a lengthy and extremely costly proposition that many contractors aren’t financially equipped to pursue. And there’s a reluctance to bite the hand that feeds, he notes.

“It takes real determination to actually sue a government agency that’s also a potential client,” he says. “You might win the lawsuit, but then it might perhaps be very difficult to get future contracts with that government body.

“As such, finding plaintiffs with both the resources and the determination to begin a lawsuit is rare. And that’s why many of these programs continue to exist today.”

Lawsuits brought against municipalities and the like often are settled out of court. The upshot: There’s no additional legal precedence set or judicial opinions issued, La Noue says.

No competition, no growth

Set-aside programs also can stunt the development of disadvantaged companies. By creating an environment where these companies aren’t held to the same standards as everyone else, they may not progress and grow in the same way they would if forced to compete, Clegg says.

“Take a minority-owned company that’s not required to submit competitive bids to get contracts, for example,” he says. “There’s no incentive for the company to improve to the point where it can submit competitive bids” without set-asides.

Observers also point out that preferential contracts can set up businesses for failure, in much the same way that affirmative action quotas at colleges and universities sometimes sent academically ill-equipped students to schools where they couldn’t keep up. In fact, some studies show that the failure rate of companies that graduate from set-aside programs is higher than the normal failure rate for small businesses.

Furthermore, as was the case with the Croson lawsuit, sometimes there just aren’t enough qualified companies to fulfill set-aside requirements. And because a set-aside program can’t magically conjure up eligible participants to compete, it instead creates a vacuum.

“And someone inevitably will try to fill that vacuum dishonestly,” Esenberg says.

Broad classifications

Another point to consider: Not all minorities are disadvantaged, La Noue observes, which raises the question of whether ethnicity, race or gender are appropriate categories to identify who is disadvantaged and who is not.

Even if people classified as, say, a racial minority truly are disadvantaged, they eventually can reach a point where they’re not. In some instances, that’s when companies graduate from set-aside programs, like Sonag did.

Graduation requirements vary widely on state and local levels; some impose time limits or income thresholds as criteria, while others have no graduation standards. Generally speaking, companies in federal set-aside programs graduate either after nine years in the program or when their average annual revenues in a three-year period exceed the small-business size standards developed by the North American Industry Classification System code.

“But in most programs, there is no graduation provision,” La Noue explains. “So, if a prominent professional athlete buys a construction firm and that athlete is African American, that business would qualify as a disadvantaged firm even though there’s no evidence it ever suffered from discrimination. Eligibility turns on the owner — doesn’t seem right, does it?”

Esenberg echoes La Noue’s sentiments, noting that it would be difficult to make a case that all women, for instance, are a disadvantaged class. “That one surely seems susceptible to challenge,” he says.

Classifying all gay business owners as disadvantaged — as the City of Chicago is proposing, led by Mayor Lori Lightfoot, the city’s first openly gay mayor — poses a similar problem. For such a proposal to pass constitutional muster, it would require evidence that discrimination is stunting the creation of gay- or lesbian-owned businesses.

“And I don’t really see any evidence of disadvantaged gay- and lesbian-owned businesses,” Esenberg says. “You wouldn’t be able to win that argument by saying there’s cultural prejudice against gays and lesbians.”

La Noue agrees, noting there’s no compelling reason to include those groups as disadvantaged even if there’s political interest in doing so.

Where’s the proof?

A similar proposal in Chicago 16 years ago to set aside city contracts for gays never gained traction. And interestingly enough, pushback came from both inside and outside the gay community, with critics arguing that all gay white men could hardly be considered disadvantaged.

Moreover, critics noted that it’s difficult to stop fraud stemming from people who pose as gays or lesbians. And if city contracts get set aside for gay white men, for example, that results in fewer contracts for truly disadvantaged business owners.

In a recent article in the Chicago Sun-Times, Chicago Ald. Walter Burnett emphasized that concern during a January meeting of the City Council’s Committee on Contract Oversight and Equity. “They (African Americans) are concerned this is another way for white males to get more contracts … that was the same concern that some African Americans had about white women being considered a minority,” he said. “And after that, we started getting fraud where white women were fronting for white males. We found a lot of corruption.”

Clegg concurs, noting that some set-aside programs end up discriminating against some groups — Asian Americans, for example — by giving preferential treatment to other groups. “All kinds of ironies result from this approach,” he says.

A possible remedy

So, what’s the alternative to set-aside contracts? Total transparency in contract bidding would reveal discrimination, Clegg says.

“It is very unlikely that in 2020, the only way to end race discrimination in contracting is through race discrimination in contracting,” he says. “When you think about it, awarding contracts is peculiarly amenable to correcting any problems through more transparency.”

This could be achieved by publicly announcing bid opportunities and then publishing all bids after a contract is awarded. If an African American-owned firm submitted the lowest bid but didn’t get the contract, for example, the discrimination would be obvious, he says.

“Either you submit the lowest bid or you don’t,” Clegg says. “This is a more narrowly tailored way to remedy discrimination than using racial preferences.”

Furthermore, if companies are discriminated against during the bidding process, the guilty parties should be punished, Clegg explains in the form letter that the Center for Equal Opportunity sends to government bodies considering set-aside programs.

In the end, Esenberg says, even though case law may continue to evolve, one thing is certain: Set-asides just aren’t the answer to ending discrimination.

“In my view, if you’re going to get past race, you just have to get past race,” he says. “But when you double-down on making race a category on which the government can act, you just wind up promoting backlashes and identity politics.

“My general thinking is that government just should not play a role in this,” he adds. “The most likely way to achieve that objective is by letting the market work.”

Ken Wysocky of Whitefish Bay is a freelance journalist and editor.

The history of government set-aside programs

Set-aside programs are designed to help small businesses owned by minorities and other disadvantaged groups gain footholds in markets where it’s difficult to effectively compete against larger competitors with more resources. This is accomplished by setting aside a certain portion of contracts that are awarded only to companies owned by minorities or disadvantaged people.

Set-aside programs for federally funded projects generally operate under the auspices of the Small Business Administration (SBA). In broad terms, eligible companies must be at least 51% owned and controlled by one or more socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, including African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans and other disadvantaged groups, such as women and service-disabled military veterans.

Almost all preferential contracting programs require business owners to seek certification as a Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) for federal procurement or Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise (MWBE) for state and local procurement.

The seeds for set-aside programs were sown decades ago. As far back as 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order that prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color or country of origin when awarding defense-related contracts. While not specifically a set-aside program, the policy marked one of the federal government’s first forays into boosting opportunities for various racial and ethnic groups.

That effort continued in 1953 with the creation of the SBA, which was tasked with helping small business grow. That mission evolved more toward helping disadvantaged business owners under the administrations of Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

In 1977, Congress approved a law that allowed the federal government, under the auspices of the SBA, to set aside a percentage of contracts for which just small businesses could compete. A year later, the SBA’s set-aside authority was expanded to include the now-familiar racial and ethnic preferences, based on the 51% ownership criteria.

In fiscal year 2018, the latest year for which figures are available, small and disadvantaged businesses were awarded $29.5 billion in federal contracts, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service released in September 2019. That included $9.2 billion in set-aside awards and $8.6 billion in sole-source awards, in which contracts are awarded without competition.

— Ken Wysock