Public-private hybrids underperform and are fraught with risk

Wisconsin has always struggled to attract venture capital. But this does not mean the solution is to involve state government, as Gov. Tony Evers has proposed.

Government-funded venture investing is a proven bad idea. The many experiments with state-sponsored funds have shown that government, even with all of its resources, doesn’t play the venture capital game well.

The existing data supports the conclusion that government-run funds generally make poorer investment decisions than private-sector venture funds. The United States venture capital system is the envy of the world, with returns of 25% or more per year, compared to the roughly 10% returns on publicly traded stock. It remains a largely private-sector operation unhindered by government, testimony to the value of our free enterprise system and the reason the U.S., at least for the time being, leads the world in innovation.

At 5%, the U.S. has by far the lowest level of government venture investment in the world, according to an analysis by the National Bureau of Economics Research (2010). Countries such as China, Canada, France and Germany are often at more than 50%. U.S. private venture capital consistently outperformed publicly funded efforts in other countries, the study said.

Consistent with the higher return of venture capital is the risk. Half of startups fail, and maybe a quarter roughly break even. Only one or two in 10 offers the 100 times or more return on investment that venture capitalists seek. Picking winners is the province of experienced investors with a track record of success, unfettered by the government’s poor decision-making, meddling and lack of expertise.

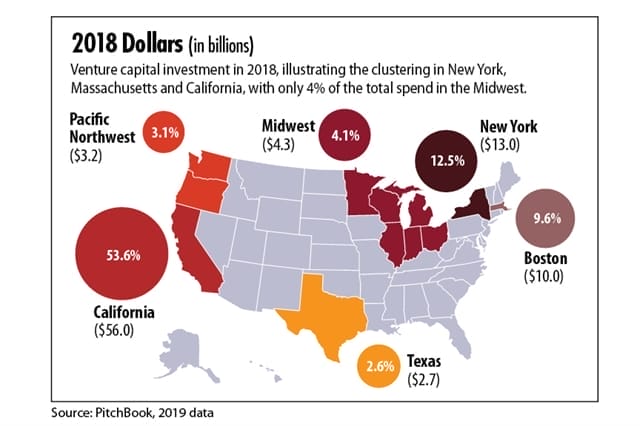

Those fund managers are clustered primarily in the Silicon Valley, New York and Massachusetts, where 84% of venture capital assets are under management, according to the National Venture Capital Association. In 2019, 1,473 venture capital deals were done in California, 525 in New York and 265 in Massachusetts. This compares to 91 in Illinois and 19 in Wisconsin.

State lags badly

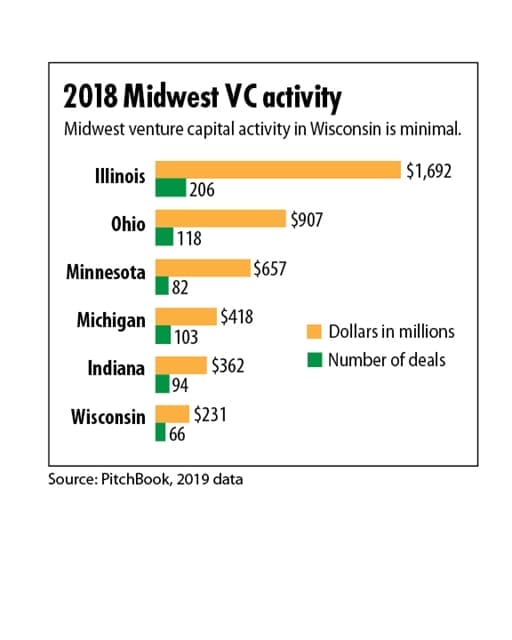

Wisconsin ranks at the very bottom of venture investing in the Midwest (see Figure 1) with $570 million in assets under management in 2019. California had $125.4 billion in that same year (see Figure 2 for the disproportion in all states).

Wisconsin has gotten better since 2001, when I moved back home to Milwaukee from San Diego. But there is still only one venture capital firm in all of Wisconsin — Venture Investors — that has the needed expertise and resources for capital-intensive investments, such as health care startups developing new therapeutics.

Many venture capital investors view Wisconsin — and all of the Midwest, for that matter — as a flyover between coasts, proximal to their home bases where they often invest with other resource-rich firms as a syndicate. Syndicates outperform individual investments with their checks and balances on investment decisions.

Wisconsin has few such venture firms that can make a $10 million to $15 million investment contribution to a syndicate. Fewer than 10 are capable of $2 million to $5 million for early-stage tech companies.

The Badger State does have some successes, such as the companies Promega, NimbleGen, Third Wave and Exact Sciences. But more often, we have firms that invest in less risky companies that already have revenue, such as Capital Midwest Fund and Baird Capital.

Republican legislators in June refused to budget $100 million for another so-called Fund of Funds called for by Gov. Evers. There was some support. Local venture firms would welcome new partners to syndicate with on larger investments, and some private venture capital professionals I have interviewed believe matching funds from the state would entice coastal firms to have a presence in Wisconsin. The reason the U.S. excels at venture capital, however, is the extent to which we emplace free markets with minimal government intervention. Government cannot attract the experts who know how to do this investing well because it cannot pay them what they earn in the private market –and they prefer to have the freedom to locate where the deal flow is.

Because of this reality, most proposals for publicly funded venture capital are designed to require matching from private funds, usually 2-to-1 private to public, with private fund specialists, not bureaucrats, making the investment decisions.

It is argued that the public money is a kind of economic multiplier or catalyst, to use a chemistry analogy, for the private venture capital market. (I am a chemist, by the way.) But to make this work without the catalyst “poisoning” the private-sector reaction is a significant challenge. The catalyst — government — cannot be involved in strategic investment decisions, even indirectly, if investments are expected to succeed.

Limited government involvement is articulated very well in Josh Lerner’s excellent book, “Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed, and What to do About It.”

Like Lerner’s recommendations, the Evers Fund of Funds plan proposed a 2-to-1 private-public match and the quasi-governmental Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. (WEDC) to help keep government at arm’s length.

In practice, such a structure is vulnerable to what economists call rent-seeking or what pundits call crony capitalism. Opportunists will look to curry favor with elected officials, fund managers and WEDC to tip the balance toward some individual or company.

Wisconsin has operated a smaller Fund of Funds, but it’s too soon to assess if it is working. So far, Madison-based Curate has provided the only successful exit.

An alternative to a public Fund of Funds (FoF) is a corporate-funded FoF, like Wisconsin’s new NVNG fund (nvngia. com). Ohio’s Cintrifuse FoF and Michigan’s Renaissance Venture Capital have reported relatively successful experiments as private funds. These remain experiments to be monitored, but at least they rely on the private sector and free markets.

Cautions for public-private Fund of Funds

Should Wisconsin lawmakers decide to create a larger publicly funded venture capital pool, I offer this advice:

• Match private and public funds, with the private funding dominant by a factor of at least 2-to-1.

• Provide oversight from a quasi-governmental organization like WEDC, but require all investment decisions to be made by experts in the free and private market, with no preference given to funds based on potentially subjective criteria from elected or appointed government officials.

• Keep the fund manager out of any discussions involving the funds to match or the selection of investments, other than to ensure compliance with statutory requirements and predefined matching criteria. These decisions should be largely formulaic, as is the case for the very effective QNBC system.

• Require diversity in syndication with at least two private firms to create the checks and balances that decrease the chances of poor investments and discourage rent-seeking and bias by government appointees. Discourage repeat investment by the same syndicates.

• Encourage syndication with investors from outside of Wisconsin to increase smart investment, bring funding into the state and prompt experienced coastal venture capital firms to open branches here. But minimal deal flow likely will remain a barrier so perhaps only smaller firms would consider branches in Wisconsin. Still, that would be a positive start.

• Require the demonstration of tangible economic impact, either by investing in startup companies incorporated in or with most of its employees in Wisconsin. This requirement should be reasonable and flexible, erring on the side of the success of the company and, ultimately, of the overall investment.

The private U.S. venture capital system’s support of worldchanging technologies has brought with it unprecedented economic growth, prosperity and well-being. Whatever we do to bring more capital into Wisconsin, let’s allow the free market to keep working its magic.

If we are to consider a public-private hybrid of this already proven system without considering the costs and potential dangers deviating from it, we risk poisoning the already small venture capital well in our state and wasting precious taxpayer dollars.

Daniel Sem is president of CU Ventures and dean of the Batterman School of Business at Concordia University Wisconsin in Mequon. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.