Wisconsin stumbled early getting shots into arms. Here’s what happened.

Back in early January, Marty Garofalo was a man on a mission: Get a COVID-19 vaccination for his wife. STAT.

“I wasn’t as concerned for myself as I was for Terry Lee, who has a compromised immune system and asthma,” says the 66-year-old Menasha resident, a retired clinical researcher for a papermaking company.

But like so many Wisconsinites during the early stages of the vaccine rollout, Garofalo faced a bewildering maze of dead ends as his hunt progressed.

“It was frustrating because no matter where I went or who I tried to contact, no one had an answer,” he says. “The default comment always was, ‘When it’s ready, we’ll contact you.’ ”

Then completely by chance, Garofalo hit the jackpot. A friend in Appleton saw comments Garofalo had posted on a media Facebook page about his vaccine-search travail and told him about a medical group that was taking appointments. After numerous phone calls, Garofalo finally got through and secured appointments for him and Terry Lee, 72.

The couple received their first dose on Jan. 21 and their second on Feb. 11.

“We got lucky,” Garofalo says. “If my friend hadn’t seen that post on Facebook, I might still be waiting. My friend now has a very expensive bottle of wine.”

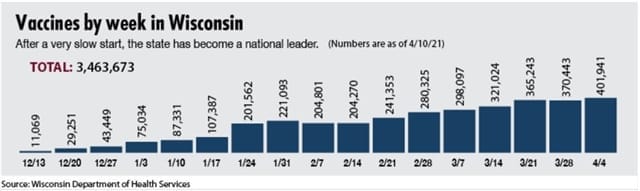

Garofalo’s experience was not unique during the problematic launch of the COVID-19 vaccination program in Wisconsin. In early January, the state ranked last among the 12 Midwestern states and 44th overall in terms of percentage of doses administered. Gov. Tony Evers and his administration faced criticism for its seeming paralysis.

However, by the first week in March, Wisconsin ranked first in the nation in percentage of vaccine doses administered, at 92% of all doses received. As of April 9, Wisconsin ranked second, having administered 3,367,885, or 86.56% of the vaccines the state had received.

What went wrong during those early months, and how did the state rebound? There were easy targets for blame in the early going: the federal government, the state government, a failure of coordination and communication between the state and local agencies. Or a patchwork quilt of websites rather than a centralized clearinghouse for vaccine sign-ups.

And last, but certainly not least, a shortage of vaccines. Demand swamping supply created havoc and frustration for untold numbers of Wisconsinites and forced many, like Garofalo, to fend for themselves.

Building a plane while flying it

To get at the root causes means avoiding the usual, simplistic political blame game. The Badger Institute reached out to nearly 20 officials at various institutions, agencies and organizations, including the state Department of Health Services, universities, county public health departments and hospitals/medical facilities.

Many declined to talk, most notably officials for DHS, whose spokesperson repeatedly declined interview requests, saying staff was too busy.

But those who agreed to speak described what it was like to build a vaccination center network of hospitals, pharmacies, clinics and local health departments, from more than 1,000 in early January to more than 2,000 as of March 18.

Every organization that wanted to be a vaccination center went through a registration process with DHS. Every week, DHS waited to find out from the federal government how much vaccine it would receive. When vaccine requests outstripped supply, DHS used criteria developed by the State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee (SDMAC) to allocate vaccines.

The Moderna vaccine is shipped directly to vaccinators, while the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, which requires ultracold freezer storage, is distributed to eight regional hospital hubs for dispersal.

It sounds straightforward, but it’s not. Andrea Palm, former DHS secretary who is now President Joe Biden’s nominee for deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, compared it to building an airplane while flying it.

“I think that’s an apt analogy,” says Dr. John Raymond, president and chief executive officer of the Medical College of Wisconsin. “This is a huge, complex task that’s really unprecedented for this generation in terms of mobilizing resources and overcoming logistical challenges very quickly.”

Raymond calls the state’s slow start a fair criticism. And while the federal government should get some credit for helping to expedite development of vaccines, he says, it failed to provide adequate coordination and communication at the state and local levels. Creating a standardized scheduling app for all states, for example, would have been better than having the states build their own websites, he says.

In addition, when the state announced in January that people 65 and older were eligible for the vaccine, health care systems like Ascension Wisconsin, Aurora Health Care, Froedtert Health and ProHealth Care, among others, appeared from their social media posts and comments to be at varied levels readiness and supply. Eligible patients in some systems were contacted within days to schedule their vaccine, while others, like Garofalo, heard nothing from their system for weeks or even months.

Refrigeration bottleneck

The character of the vaccines posed logistical problems at the start. The Moderna vaccine must be stored at temperatures between 36 and 46 degrees. The Pfizer vaccine requires ultra-cold freezer storage — between minus 112 and minus 76 degrees — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

During the first several weeks of the vaccination program, Wisconsin received and administered significantly more doses of the Pfizer vaccine, unlike higher-performing states such as West Virginia, Raymond says.

In addition, DHS had to develop a system to track who is vaccinated and how to contact them for second doses. Training and certification of vaccinators probably added several days to setting up each clinic, he says.

“I think it’s the professional thing to do … you need personnel on site that can administer doses in a way that’s consistent with utilizing a very precious resource,” Raymond says.

Vaccination sites also had to accommodate social distancing as well as provide sufficient parking and adequate snow and ice removal to keep elderly people safe.

“We shouldn’t be apologizing for having all these mechanisms in place,” Raymond says. “All of these challenges were huge.”

‘Last-mile’ issues

Fluctuating amounts of vaccine shipped from week to week on the federal end and a lack of control over vaccination scheduling on the local end presented some of the biggest challenges to the logistics of “last-mile” delivery, Laura Albert says.

Albert is a professor of industrial and systems engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her specialties include public-sector operations research, including vaccinations.

“It’s really, really hard — a pretty massive technical challenge,” Albert says. “Just a slight blip in vaccine production leads to fluctuations in what gets delivered.”

People who cancel or don’t show up for their vaccinations, or who make multiple appointments and don’t cancel the others when they get their shots, only add to the uncertainty, she says.

There also have been some problems with websites. In early February, for instance, the Washington/Ozaukee Public Health Department website crashed after receiving 45,000 hits in a single hour from users jockeying for just 500 appointments. A couple of weeks later, the website stopped taking appointments because the vaccine wasn’t available.

Dr. Jonathan Temte, associate dean for public health and community engagement at the University of WisconsinMadison School of Medicine and Public Health, contends that underfunded public health agencies contributed to the slow rollout. Wisconsin ranks 46th in per capita funding for public health, according to DHS statistics.

“When you talk about taking on vaccinations for all the adults in the country over a short period of time, you have to have the resources to do so,” he says. “But our state, county and municipal public health departments are all underfunded. If those institutions were better staffed and better funded, it certainly would help … but there just isn’t enough bandwidth there.”

Supply chain deficiency

Doug Fisher, director of the Center for Supply Chain Management at Marquette University’s College of Business Administration until his retirement in 2019, expressed both personal and professional criticism of the vaccination distribution system.

Fisher registered for a vaccination at multiple sites — his health care provider, the City of Milwaukee and a grocery store chain. None could tell him even approximately when he might get a shot.

“It’s totally frustrating — like it’s tax season and no one can get a 1099 form,” he says. “And I know I’m not alone.”

Based on three decades as a supply chain expert, Fisher says the state would have benefited from calling on corporate executive and military officials with that kind of expertise. “I don’t get the impression that this was done,” he says. “Government administrators aren’t supply chain experts … they don’t seem to be able to execute things well.

“If this was packages coming late for Christmas, I wouldn’t care so much,” he adds. “But the vaccine is the Holy Grail for stopping the virus.”

Any endeavor overseen by government inevitably invites political criticism. State Rep. Joe Sanfelippo (R-New Berlin) was sharply critical early on because he said the Evers administration put politics over vulnerability in deciding who should get vaccinations first.

“It’s just ridiculous to be so mired down in bureaucratic red tape and politically correct ideas about who should be first or second in line and so forth, rather than focusing on vaccine distribution,” Sanfelippo says. “I’ve never seen a more inept group of people with such an immense responsibility fall on its face the way this administration has.”

The rebound

Since the initial rollout, vaccinations are on the upswing. As of April 14, 38% of Wisconsinites, or 2,214,114 people, had received at least one vaccine, according to DHS data. And more than 25% of the population had completed the program.

The state has received substantially more vaccine doses in March than it received per month in January and February, as Moderna and Pfizer continue to ramp up production.

And local vaccination sites continue to open, perhaps most notably in Milwaukee. City health officials in late March designated North and South Division high schools as large, long-term, walk-in sites for underserved residents who live within 10 specific ZIP codes.

Raymond thinks the vaccine supply-demand imbalance could be resolved by May, especially because a third vaccine, produced by Johnson & Johnson, received emergency use authorization. Unlike Moderna and Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson is equipped to manufacture the vaccine without a lot of ramp-up time, he says.

Since we spoke to Raymond, the CDC on April 13 recommended J&J pause distribution of the vaccine to study blood clots that developed in a handful of women days after receiving their shots.

Regardless of the approach Wisconsin took at the start, officials have tried to do the right thing, Temte says. “And at the end of the day, it blows me away that 19% of the state’s population (at the time of the interview) now has at least one dose of vaccine,” he says. “I never would’ve thought this could be possible a year ago.”

Mixed emotions

When the rollout began, Kathy Cowan began looking for a vaccine immediately. A biking accident in June 2020 left her husband, Mark Fischer, paralyzed from the chest down.

“We were told many times that getting COVID would kill him,” Cowan says.

But Fischer wasn’t eligible because he won’t turn 65 until August. Cowan, 61, of Grafton, refused to accept it. She frequently visited a local hospital and made calls that led to nothing.

Then on Valentine’s Day, the boyfriend of Cowan’s daughter, Katie Fischer, told her the Madison pharmacy where he worked had leftover doses and that his parents were willing to give up their doses for Kathy and Mark.

“We were so touched by what they did,” Cowan says.

Like the Garofalos, Cowan still is frustrated about what she went through. She knows of other people with no underlying health issues who got vaccines before her and her husband. But both families agree the vaccination program is a major undertaking.

“Sloppy is the word I’d use,” says Cowan. “But I know they’re trying and that this is all brand new. The only silver lining in all of this is that maybe by the next pandemic, they’ll have figured it all out.”

Ken Wysocky of Whitefish Bay is a freelance journalist and editor. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.