Local filmmaker links Wisconsin incident to origin of Republican Party

A heroic moment in Wisconsin’s history deserves a lot more attention, says Michael Jahr. So he’s making a movie about it.

“There are some stories that are so amazing, you say, ‘How could I have never heard that before?’” said Jahr, who — full disclosure — was my colleague at the Badger Institute until last year. Now he’s writer and director on a team making a documentary about the Joshua Glover episode, the time when a lot of Wisconsinites defied federal law to save a man from being dragged back into slavery.

Like all good memorials, this recounting has some lessons for us.

Glover’s story isn’t wholly unknown. Jahr said he’d read the plaque in downtown Milwaukee and ran across a gripping account at an estate sale. Murals at an I-43 underpass on downtown’s edge commemorate it. On Monday, Jahr and colleagues premiered the first version of their work on a particularly high-profile stage, the Republican National Convention.

It’s quite a tale. Glover was living in Racine in 1854, two years after he escaped slavery in Missouri, when a bounty-hunting posse found him and dragged him off to Milwaukee’s jail, intending to return him to bondage. Their warrant was based on the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law that bound officials and even citizens in every state, including those like Wisconsin that never were cursed with slavery, to refrain from helping fugitives and to cooperate with recapturing them.

In abolition-minded Wisconsin, “that was anathema,” said Jahr. “That was horrific.”

Racine abolitionists outraged by the bounty hunters’ abduction of a free man set off for Milwaukee by boat the next morning, bringing a sheriff to arrest the posse, and telegraphing like-minded Milwaukeeans, among them Sherman Booth, editor of an abolitionist newspaper. Booth rode through the streets shouting that a man’s liberty was at stake, drawing a crowd estimated at 5,000 to the jail.

When it became clear the crowd’s demands, that Glover receive due process and not be jailed over the sabbath, would not be met, men used a beam from a nearby construction site to batter their way into the jail, freeing Glover. “He was cheered, almost like a celebrity,” said Jahr, and was whisked away in a waiting wagon, first to Prairieville (now Waukesha), then after some weeks of being hidden from the still-prowling bounty hunters, on a boat to Canada and safety.

In Wisconsin, the matter wasn’t over. “There was great risk,” said Jahr, “not just for the underground railroad moving him along, but for the rescuers.” The Missourian claiming Glover as property sued Booth, who eventually was financially ruined. The rescuers’ criminal cases for violating the hated law volleyed back and forth between state and federal courts for years — Booth spent time behind bars — with the Wisconsin Supreme Court eventually discarding the federal Fugitive Slave Act in Wisconsin.

“This enraged the South,” said Jahr. “All these events in Wisconsin served to drive a wedge between North and South.”

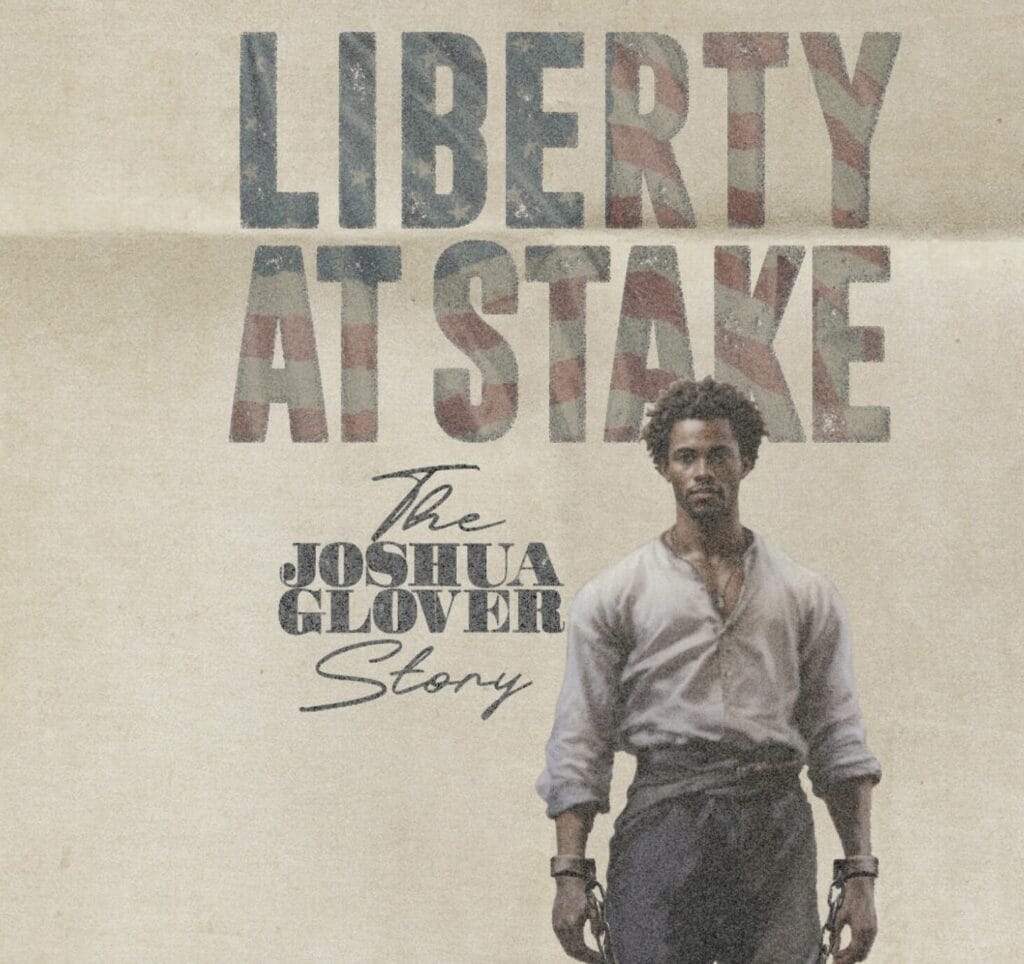

Jahr and his colleagues are looking to offer an expanded version of the documentary, titled “Liberty at Stake,” by next spring to broadcasters or educators. They wanted the 12-minute convention-length version — you can see it at Vimeo — ready by the time 50,000 visitors came to town “because it’s a Milwaukee story, a Wisconsin story,” as Jahr said. As Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson says in the documentary, it’s one with universal appeal.

“It goes to the heart of how passionate people were about freedom and what America was,” said Jahr.

That’s a key lesson: That the Civil War was fought on the understanding that for some states to deprive some Americans of their natural endowment of liberty was an injury to all. It could not remain a matter of if-you-don’t-like-slavery-don’t-own-a-slave — not just because the status of western territories was in question but because a federal law had conscripted Wisconsinites into what they saw as evil. The logic of slavery consumed every American’s liberty.

The second lesson: In a republic, the law has limits, and it’s up to citizens to hold government to account for violating them — by battering down a jail door or by Wisconsin Supreme Court justices daring to nullify a federal law.

A third lesson comes from what happened only nine days after Glover was freed: Booth and other abolitionists, politically homeless from the failure of smaller parties to challenge the dominant Democratic Party, “recognized, against the odds, that a new party was needed,” said Jahr. They met in a schoolhouse in Ripon to form one, dubbing it the Republican Party, and six years later, its candidate, Abraham Lincoln, won the White House.

Divided on other issues, “the one thing that unified them was their absolute commitment to the founding ideals of liberty for all,” said Jahr. In other words, Glover’s rescue couldn’t be a one-off.

In Wisconsin elections, “very quickly, they displaced the pro-slavery party,” said Jahr. “It really is a model for how a grassroots movement can influence politics and culture at large.”

To be sure, that influence led to a civil war. But it’s not too much to say that Wisconsin’s blow against slavery helped save America’s soul. It’s a moment worth remembering.

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields