Hordes of Wisconsin government workers are employed to ‘check boxes’ for the feds

The official name of the state’s big job-training agency is the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development. But with the federal government issuing the paychecks for almost three-fourths of the department’s workers, a cynic might suggest that the United States Department of Workforce Development is more accurate.

Fully 71 percent of the 1,632 workers at DWD are paid with federal funds, part of a slow takeover of that state government agency.

The story is the same at other major Wisconsin agencies:

- 47 percent of employees at the Department of Public Instruction are paid by the federal government.

- 46 percent at the Department of Children and Families.

- 23 percent at the Department of Transportation.

- 19 percent at the Department of Health Services.

- 18 percent at the Department of Natural Resources.

All paid with federal funds, mostly in the form of federal grants.

And the federal presence in Madison is growing. Twenty years ago, there were 4,382 full-time equivalent employees in state government (not counting the University of Wisconsin System) paid with federal dollars, according to budget documents reviewed by the Badger Institute. Today, there are 4,987 — an increase of 14 percent, which represents more than 600 positions and tens of millions of dollars of additional annual spending.

Not all of those people, or those dollars, are delivering services to people — the unemployed, the poor and sick — or used directly to build highways or clean polluted waterways. A hefty chunk of that cash is going toward paying people to make sure rules are followed, audits are completed and paperwork is processed.

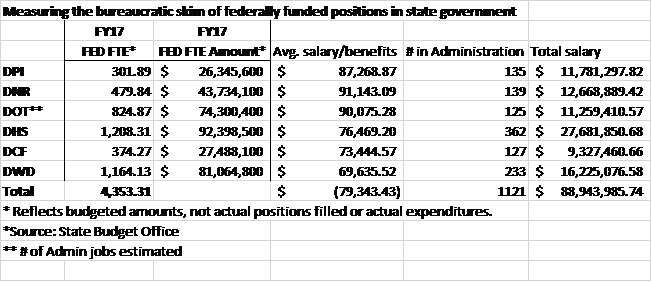

A Badger Institute analysis of the six departments listed above found that over 1,100 of their federally paid employees are engaged in administrative work, earning an average of $79,343 a year in salary and benefits, totaling almost $89 million.

“Whenever the federal government entices states to accept funding, the funds always come with rules and regulations which expand the bureaucracy, grow the size of government and increase costs to taxpayers, says state Sen. Dave Craig (R-Town of Vernon), chairman of the Senate Committee on Financial Service, Constitution and Federalism. “This has been seen most prominently in school funding, highway funding and Medicaid. However, the other more insidious problem with federally backed employees and programs is letting state officials off the hook from having to make tough budgetary decisions.”

The emphasis is not on achieving outcomes but on rules compliance and who gets credit for spending the money.

“Federal aid stimulates overspending by state governments and creates a web of complex federal regulations that undermine state innovation,” says Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., and editor of downsizinggovernment.org. “At all levels of the (federal) aid system, the focus is on regulatory compliance and spending, not on delivering quality public services. It is a triumph of expenditure without responsibility.”

For instance, a recent federal study found the Obama administratiion spent $7 billion on the nation’s schools through the School Improvement Grants program, meant to help needy students in low-performing schools, but the spending had no discernible effect.

Federal influence in Wisconsin

The federalization of Madison is, perhaps, not surprising in some areas like the UW System — which publicly boasts of trying to maximize federal grants for research — or in the Department of Health Services. The rise in Medicaid costs is a well-known phenomenon.

But given Wisconsinites’ preference for local government and local schools, they may be surprised at the extent of federal influence in the rest of state government. Which begs the question: At what point does a federal paymaster start taking de facto control of an organization in which it supplies cash for workers doing its bidding?

“Without a question, those positions are carrying out (policy) based on what the people in Washington want,” says state Rep. Joe Sanfelippo (R-New Berlin).

The federal intrusion into state government is setting off alarms across the country. Big federal programs like Medicaid and federal highway funding are turning states “into mere field offices of the federal government,” writes Mario Loyola of the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty.

A Badger Institute analysis finds that about one-fifth of the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development’s federally paid employees — 233 workers, earning an average of $69,635 a year in salaries and benefits, according to the state Budget Office — work at jobs simply administering the flow of those federal dollars and checking who does what for which federal program. Like a Beltway-based Santa Claus, they have lots of lists and are checking them a lot more than twice.

One example: DWD uses federal funds to pay for an administrative rules coordinator in the agency’s unemployment insurance division. That employee is responsible for coordinating the administrative rule-making process for DWD, including the drafting of administrative rules, submitting proposed rules to the Rules Clearinghouse and recommending to the top official at DWD priority areas for rules development.

Which DWD worker qualifies for a federal paycheck as opposed to a check paid out of state funds is determined by the program the employee works on and whether federal grant monies are available for that program, says DWD’s Communications Director John Dipko.

For example, one of the divisions within DWD is the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. DVR obtains most of its funds — nearly 80 percent — from the U.S. Department of Education. Only 21 percent of the division’s money comes from state coffers.

That translates into more than $65 million from the federal government and $17.6 million from the State of Wisconsin — a total of more than $82 million annually in federal fiscal year 2016.

It’s been that way for more than a decade, DWD spokesman John Dipko said.

Earlier this year, “DWD conducted a review of workforce-related programs and federal mandates in Wisconsin. Following that review, DWD requested relief from requirements that unnecessarily add cost to taxpayers and impact our commitment to making state government more efficient, effective and accountable to the citizens of Wisconsin,” Dipko said in an email. Changes would help streamline some data reporting and relax some reporting requirements to allow more innovation by the state.

The same pattern shows up throughout state government. There are 797 employees in the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. Almost half of the workers — 374 employees, or 46 percent — are classified as federal full-time equivalents and are paid with federal dollars. About one-third of those federal FTEs — 127 employees, at an average salary of $73,445 — work in administration.

Of those, there are 40 employees in the Bureau of Program Integrity in the department’s Division of Early Care and Education. One of their jobs: “Coordinate the review and analysis of federal regulations and state statutes to determine the need for administrative rules, manual materials and other materials.” Other jobs include coordinating new laws and revising existing laws to reflect the objectives of department initiatives and developing plans to minimize the risk of fraud and overpayment in child care subsidies.

The Department of Natural Resources is another of the state’s larger agencies, with 2,549 full-time equivalent employees. Of those, 480, earning an average salary of $91,143, are paid with federal funds — 18 percent of the total department workforce.

Administrative jobs abound

About 29 percent of the federally paid DNR workers — 139 — work in administrative or support jobs. For example, 41 work in information system or information management jobs. Another dozen work as policy/program analysts or administrators, six as accountants and another seven in the department’s legal shop. There are five FTEs in the department’s real estate section and four in its payroll and personnel department. There are two more federal FTEs in the department’s equal opportunity and visitor services offices.

Like other state agencies, whether DNR employees are paid with state funds or with a federal paycheck depends on the division or bureau they work in and, more specifically, whether the type of work they are doing “is federal grant-eligible or not,” says James F. Dick, the DNR’s communications director. “State-to-federal match requirements and variability in the amount of grant funds the department gets from year to year can also impact whether staff work is federally funded or state-funded,” Dick adds.

The Department of Health Services has nine major departments staffed by federally paid employees: Public Health, Medicaid Services, Care and Treatment Services, Quality Assurance, the Secretary’s Office, Enterprise Services, Office of Legal Counsel, Office of Policy Initiative & Budget, and Office of Inspector General.

The department employs 6,104 workers, of which 1,208 — or 19 percent — are paid with federal dollars. Many work on the big Medicaid program that provides health care for the poor. Almost 30 percent of the federal workers can be classified as performing administrative or support services, earning on average $76,469.

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation is one of the biggest agencies in state government — with 3,494 employees. Almost a quarter of them — 824 — are paid an average of $90,075 in salary and benefits with federal dollars, largely because of the massive federal highway funding to the state. DOT’s total budget is $5.67 billion — of that, $1.65 billion comes in as federal funds.

It’s unclear from records provided by the DOT how many of those federal FTEs are employed in managing the flow of funds from Washington, further illustrating how murky the bureaucratic waters are when trying to ascertain the administrative suck of federal funding. But a conservative estimate of 15 percent would mean about 125 people are so employed.

At the Department of Public Instruction, about 45 percent of 301.89 federal FTEs, earning an average of $87,269 annually, according to the budget office, appear to be involved in purely administrative work — accountants, grants specialists, administrators, attorneys and human resources personnel — not in classroom work.

Ted Neitzke, the former superintendent of the West Bend School District with more than 22 years in the education field and now head of a regional education agency, says the paperwork to administer federal grants in Wisconsin is overwhelming.

“DPI — they got a jillion people working there that are just checking boxes,” Neitzke says. “The paperwork — it needs to be checked 52 ways to Sunday. I can’t even imagine how many personnel they have whose sole job is just checking boxes,”

If current trends continue, even more Wisconsin government workers will owe their paychecks to the federal government. The danger is the steady creep of federal intrusion, warns the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty’s Center for Competitive Federalism.

“In the long term, it is critical to stop, and start reversing, the federal government’s slow takeover of Wisconsin’s budget and state agencies,” the center cautioned in a July 2016 report, aptly titled “Wisconsin not Washington.”

Craig agrees.

“The federal regulatory impact on state operations continues to be a driver of inefficiencies and spending increases at the agency level,” he says. “Disentangling our state from federal overreach is ripe for reform.”

Dave Daley is a reporter for the Badger Institute’s Project for 21st Century Federalism.

► Related story: Schools often hire high-priced specialists to deal with complex federal grant rules