Even Democrats favor a right-to-work law that would end compulsory union dues from unwilling workers

Back in the 1990s, Tiffany Koehler worked part time at a delivery service distribution center in Oak Creek making a modest hourly wage that shrank even further when somebody took a chunk out of her paycheck without asking and gave it to the union.

So she did something lots of workers have done over the years but that few, back in the old days, talked about. She started asking, “Well, what does the union do?” And why should she have to join?

The answer to the first question depends on whom you ask.

The Teamsters’ national website succinctly states its view: The union was organized more than 100 years ago for workers to “wrest their fair share from greedy corporations” and, today, “the union’s task is exactly the same.” Less polemical supporters say the union pushes for higher wages, better pensions and working conditions, and even provides invaluable training.

Koehler had another perspective. She thought the union protected slackers, doubted it really secured higher take-home pay and didn’t like the union’s political bent.

The answer to the second question — why she had to join — is cut-and-dry.

She had to join because this is Wisconsin, and Wisconsin — unlike much of America — is not a right-to-work state. If you work at a Wisconsin company with a “union shop,” you have no choice but to give the union a percentage of your check and become subject to its contract. Or else lose your job.

For years, this was just accepted as a fait accompli. Wisconsin has had labor unions since the bricklayers in Milwaukee organized themselves in 1847, and you don’t have to be a socialist (though many were) to acknowledge the benefits unions fought for and won: shorter workdays, workers’ compensation, higher wages.

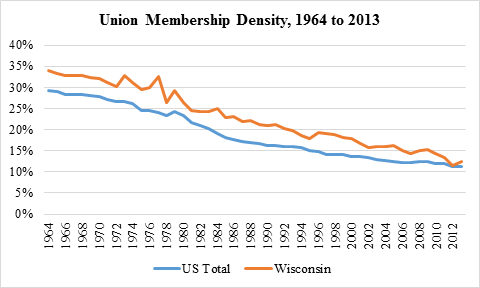

By 1939 — just four years after President Franklin Roosevelt signed the union-empowering National Labor Relations Act — union membership had grown to almost 30% of all non-agricultural workers in America. In Wisconsin, membership was as common as German lager. But, of course, beers and union membership slowly evolved into something much less stout.

Union membership has plummeted everywhere for decades. By 2014, it had fallen to 11.1% of all public- and private-sector workers in the country. The rate is slightly higher in Wisconsin — about 11.7%, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics — but still just a fraction of what it once was. Skeptics note that the percentage is even lower in the private sector, less than 7% in Wisconsin, and wonder why right-to-work legislation is even necessary.

Proponents counter that the numbers of workers and businesses impacted are still large. There were still 306,000 workers in Wisconsin’s public and private sectors who were union members, according to 2014 Bureau of Labor Statistics figures. And when you include workers who are not union members but are represented by a union contract — whether they want to be or not — that figure grows to 327,000 — 12.5% of the working population.

Sources: Barry T. Hirsch, David A. Macpherson and Wayne G. Vroman, “Estimates of Union Density by State,” Monthly Labor Review, 2001; Ohio University research calculations for WPRI

Almost 25 years ago, a Chicago labor lawyer by the name of Thomas Geoghegan wrote a trenchant book comically entitled, “Which Side Are You On? Trying To Be For Labor When It’s Flat On Its Back.”

Labor has been increasingly supine for a while but, a little north of Chicago, Wisconsinites are still largely for it, or at least sympathetic. Nearly six in 10 Wisconsinites (58%) still approve of labor unions, far more than disapprove (34%), according to a WPRI poll of 600 adults conducted by University of Chicago professor William Howell in January.

“Though there are important partisan disagreements, Wisconsinites on the whole are pro-labor and see value in unions,” says Howell. Support for unions is in Wisconsin’s genes, you might say.

“What’s interesting here is that, at the same time, most state residents — Republicans and Democrats alike — support right-to-work legislation,” he says. “The argument that workers should not be obligated to join a union in order to hold a job resonates broadly.”

They see the issue as a basic and simple one: No American should be required to join any private organization, like a labor union. More than three-quarters of Wisconsinites (77%) agree with that statement, while only 22% disagree — proof that many people who value the history of labor and are still supportive of unions are even more supportive of individual rights.

Indeed, even among Democrats — 85% of whom approve of unions — more than half (54%) say that they would still vote for right-to-work legislation.

Support for right to work among independents and Republicans is even higher — resulting in widespread support in all ideological corners of the state. All told, nearly twice as many Wisconsinites say they would vote for such legislation as against it (62% to 32%).

That said, folks on the right are a little easier to figure out on the issue. They generally see little value in unions and lots of value in right to work. Democrats are more complex. They love unions. Yet they are largely supportive of a policy that union leaders fear could destroy their movement.

Geoghegan, the labor lawyer — without alluding to right to work — put his finger on the explanation for the apparent paradox.

“Yes, there is a certain macho appeal” to unions, he wrote. “I loved being a labor lawyer, all the little pieces of stage business. Yet this was never the true appeal. … No, it was the appeal of stepping into some black hole in American culture, with all the American values except one: individualism.

“Labor thinks of itself consciously as American as apple pie. But it is not. Go to any union hall, any union rally and listen to the speeches. It took me years to hear it but there is a silence, a deafening Niagara-type silence, on the subject of individualism. No one is against it, but it never comes up. Is that America? To me, it is like Spain.”

Confusion and split allegiances on the left — the internal tug-of-war between a belief in the power of collective action and the American individualistic spirit — is palpable in a way it is not in the center or on the right. Nearly seven of 10 Republicans (69%), most of whom aren’t particularly enamored of unions anyway, say they would vote for right-to-work legislation if given the chance.

Still, that leaves over 30% on the right who are opposed. The top Republican of them all, Gov. Scott Walker, stated on Feb. 20 that he would sign legislation about to be introduced. But before that he famously called the push for right to work a “distraction” — a stance that flummoxed many supporters who watched him advocate for Act 10.

It’s impossible to talk about labor laws in Wisconsin without talking about Act 10, the budget-repair law that gutted the powers of public employee unions. Some conservatives see right-to-work legislation as a logical extension and, indeed, there is one key similarity.

While Wisconsin’s government workers had not been required to join unions prior to Act 10, they had long been required to pay the equivalent of union dues that were automatically deducted from their paychecks and handed over to the unions.

Act 10 ended that, and right-to-work legislation would similarly protect private-sector workers from being forced to pay union dues. But that’s where the similarities end. Act 10 virtually eliminated public-sector collective bargaining. In the private sector, labor rights are guaranteed under federal law. Nothing Wisconsin could do will alter that.

Private-sector workers in right-to-work states are free to negotiate everything they always have. The only difference: Rather than compelling workers to join, union leaders have to convince them to voluntarily pay dues — something business interests think will be difficult and something union leaders fear will exacerbate the ongoing decline of union membership in both America and Wisconsin.

There’s no question that over the last 150 years, unions have helped workers increase their wages substantially. That’s why the central argument of right-to-work opponents is that all workers in unionized workplaces should pay for the gains the union is responsible for. Otherwise, they say, non-joiners are just freeloaders.

But right-to-work proponents say we live in a markedly different world today. And not just because 24 states, including Michigan and Indiana, now have right-to-work laws. And not just because America now has the federal Occupation and Safety Health Administration, anti-discrimination laws, Social Security, pension plans and IRAs — all protections that have nothing to do with union membership.

WPRI polling shows that most Republicans and independents, in addition to seeing right to work as an issue of individual freedom, also believe right-to-work laws will attract businesses to Wisconsin and improve economic growth. To them, it’s simple common sense in a global economy where unions simply don’t have a monopoly on the labor supply the way they once did. Competition from cheap labor in other parts of the world, including right-to-work states in America, in short, makes capital investment in non-right-to-work states less likely. And it also gives American unions far less leverage over wages than they once had.

There are all sorts of other factors that businesses consider before investing, of course. But all other things being equal, businesses will tend to avoid investing in states where the perceived costs of unionization are relatively high. Right-to-work laws, conversely, help attract industry — and jobs — to a state. And that, goes the argument, is good for everyone.

Not everybody on the right agrees. John Gard, the former Assembly speaker, is perhaps the highest profile conservative opposing right to work. Gard, a lobbyist who represents the Operating Engineers Local 139, says there are more than 400 contractors in the state — most of whom use union labor — who oppose right-to-work legislation.

He argues that hardly anyone in Wisconsin believes right-to-work legislation should be a “top priority,” says few think they will personally benefit, and argues that right to work could eventually erode unions to the point where they will no longer be able to supply trained workers for business.

Unions such as the Operating Engineers — which includes heavy equipment operators, mechanics and surveyors among others — have a “very harmonious relationship” with the contractors they work for and “it is likely to be significantly disrupted” by right-to-work legislation, he argues. (See related story: The tiff over training.)

Gard’s other main argument is that businesses should have the right to enter into contracts with employee groups, and that government has no business intruding.

Too late, says Scott Manley, vice president of government relations for Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce. He points out that government intruded long ago by forcing companies to bargain with unions that were formed by virtue of a one-time vote requiring approval of only 50% of employees. Once businesses in unionized industries recognized union shops, he says, it became exceedingly difficult to ever reverse that.

“We are a membership organization as well,” Manley says of WMC, “and we have a recertification every year by members who decide if we are doing a good job and if they want to pay dues.” Right-to-work legislation, goes the argument, simply asks unions to demonstrate value instead of forcibly compelling membership.

While Gard says lots of construction and building trades contractors are opposed to right to work, WMC says 81% of its members support it, and the general populace — regardless of political affiliation — is solidly supportive as well.

The schism could have numerous explanations, but one in particular rings true. If you’re building a new home in Stevens Point or laying asphalt in Hudson, you don’t have to worry about a competitor in Mexico or India coming along the same way a manufacturer or a nonunionized tech-based business does. In a global economy, some folks have a little more motivation to control labor costs than others.

Union leaders such as Terry McGowan, president of the Operating Engineers, worry that right to work will drive down wages and argue that’s not good for anyone. And Act 10, though it was a very different animal, proved that changes in labor law could indeed weaken union ranks.

However, Richard Vedder, an Ohio University economist, suggests that union supporters have an unnecessarily bleak view of the future. Counter-intuitive as it might sound, Vedder raises the possibility that right-to-work laws might help labor in the long run.

Vedder points out that within the 19 states with right-to-work laws by 1980, the decline in union membership has been less pronounced than in the non-right-to-work jurisdictions. In two right-to-work states, Florida and Nevada, there was actually an increase from 515,000 union members in 1980 to 583,000 in 2013 — an 11% gain.

Clearly, population increases in those states, unrelated to right-to-work policies, are a factor in this growth. Moreover, dozens of factors impact differences in economic performance and population growth, including taxes, mix of industry, educational attainment, natural resource availability, regulatory policies, even climate. You don’t have to be an economist to know that people move to the Sunshine State because of, well, the sunshine.

But, Vedder points out, since goods and services are produced primarily from the use of labor, labor laws and regulations are potentially very important. And there can be economic benefits for everyone, including labor, from a union working harder to prove its worth. Vedder doesn’t believe that right-to-work laws should be considered “anti-union.” Rather, he sees them as pro-competition and pro-worker freedom.

Tiffany Koehler long ago left her unionized part-time job, and after a career working in the military and the nonprofit world, she recently ran for the state Senate seat vacated by Congressman Glenn Grothman. Koehler didn’t win the Feb. 17 primary. But the guy who did, Duey Stroebel, is also fervently pro-right to work — and is even willing to co-sponsor a right-to-work bill.

Capitol observers and most insiders had thought that right-to-work legislation would not be introduced until Stroebel, who does not have a Democratic opponent in the April 7 general election, is seated in April. But Republican legislative leaders say they are ready to move forward right now.

If they are able to assemble the votes and act quickly, the issue would, of course, move to the governor’s office.

And it is now clear that Scott Walker will not stand in the way of a fundamentally conservative policy change that even most Democrats favor.

Mike Nichols is president of the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.