Special needs students are left behind because of inequitable allocation of federal resources, administrators say in survey

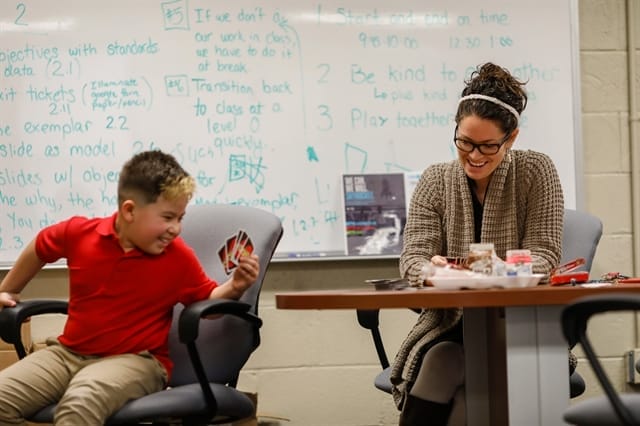

Playing the card game Uno with a small group of special education students isn’t usually one of a principal’s normal duties. But for Julieane Cook of St. Martini Lutheran School on Milwaukee’s south side, these “sensory breaks” — where she and students play board games, practice social skills and work on occupational therapy — are a vital part of the children’s routines.

Because St. Martini cannot hire enough special education teachers and none are forthcoming from Milwaukee Public Schools, which oversees federal funding for special education programs, Cook takes time away from her administrative duties to work twice a day with six to eight special education students.

“I’m also coaching all the teachers as much as I can to provide (special education) support,” Cook says.

The situation at St. Martini points to what private school principals say is the inequitable allocation of resources to disadvantaged and disabled schoolchildren under current law, affecting potentially thousands of Wisconsin children who attend private schools and are legally entitled to those services.

Funding for programs that benefit those students flows through several federal programs, primarily Title I and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. Federal law obligates state and local public school agencies to provide a “free appropriate public education” to those children.

Some children are placed in private schools by public agencies because the private school may offer services not available at the public school. If so, the child’s education is publicly funded. But even when parents choose to put their disabled children in a private school, a portion of their funding can be provided through IDEA under a formula to be worked out at the local level.

As for Title funding in private schools, federal law requires that eligible students in private schools receive “services or other benefits that are equitable to those provided to eligible public school children, their teachers, and their families.” As with IDEA, those services “must be developed in consultation with officials of the private schools.”

But many private school principals surveyed recently by the Badger Institute say the system is not working and may even be detrimental to their students.

About 62 percent of private school principals say in the survey that federal regulations sometimes prevent their students from receiving services they need in the way they desire, and 43 percent say some of their students who are legally entitled to those services are not receiving them.

“It is the students with the greatest needs that suffer,” says Jean Vander Heiden, principal of All Saints Grade School in Denmark in Brown County.

The answer, they say, is not necessarily more funding. What is needed is more communication and an improved process that better allocates funds and focuses on the needs of students, the survey shows.

Principals want federal role reduced

In fact, the less federal involvement the better, principals say in the survey.

About 59 percent say the federal government’s role in education should be reduced or eliminated, and 72 percent say at least some federal education grant money is wasted.

The Badger Institute survey was conducted from Jan. 22 through Feb. 19 and was sent by email to 562 private school principals or administrators statewide. Of those, 164 completed the survey, a 29 percent response rate.

Under federal law, private schools do not directly receive federal funding. Rather, funding for disadvantaged and disabled students who attend private schools flows through the “local education agency,” or LEA, a public school district or group of districts in which the private school is located.

That means, in most cases, special education teachers and others who work under federal programs are employees of the public school district and overseen by public school officials, not the private school. Private school officials may have little say over when or how often a special education or Title I teacher visits their schools.

“It would be nice if we could just deal with our funds directly,” says Denise Ring, principal at Aquinas Schools in La Crosse. In dealing with federal funding, she says, school officials often feel as though they’re “bothering someone” for more information on the amount or cost of services.

Over 28 percent of principals in the survey complained that their current public school district makes it difficult for them to access federally funded services for their students; 70 percent indicated they had experienced difficulty in the past.

Asked why they experience difficulty:

• 16.5 percent say, “We are a religious school and public school officials think federal funds should not or cannot be used to serve our children and teachers.”

• Another 16.5 percent say, “Public school officials don’t want to share the federal funds they receive.”

• Another 9 percent say, “Public school officials are ignorant about our right to ‘timely and meaningful consultation,’ ” citing federal law.

“Overall, the dialogue with the public school is decreasing,” says Steve Zangl of All Saints Catholic School in Berlin in Green Lake County.

One solution: Create a separate local education agency responsible for overseeing distribution of funds to private schools. That idea was introduced early in last year’s state biennial budget process but was excised and never reached the floor of the Legislature.

Justin Moralez, state director for the American Federation for Children, says the group plans to reintroduce the idea in the next budget cycle. While the bill would not mean more direct funding for private schools, it would allow for a more streamlined approach, better communication and more control, he says.

“Instead of running through the pipeline of the public school district,” Moralez says, private schools would receive the money they’re entitled to directly from their own LEA.

While most survey respondents say they are generally satisfied with their relationship with the local public school district, the vast majority — nearly 82 percent — say private schools need more flexibility and control over how their students and teachers are served by these programs.

In the survey, 58 percent of principals say the public school district oversees the federally funded staff who work in their school, while 30 percent say private school officials are allowed to do so under the auspices of the public school district. Twelve percent say they use a third party contracted by the public school district.

“It feels like a big huge bureaucracy we’re not familiar with,” says Meghan Smyth, director of education at Madison Community Montessori School in Middleton in Dane County. “There seems to be an assumption that every family that attends a private school is well-off and has access to outside services, but that’s not the case.”

In addition, private school principals need more training and education in how the system of federal school funding works and what their rights and responsibilities are, advocates say.

Federal law requires public school districts to meet with private school officials in a “timely and meaningful manner” on funding, but many private school principals say they only meet with their public school district’s special education director once at the beginning of the school year — before funding is even set. That leaves them uncertain of how much funding will be available for the year or how many students they will be able to serve.

Sharon Schmeling, executive director of the Wisconsin Council of Religious and Independent Schools (WCRIS), says it’s up to the private school principals to follow up with public school districts if they’re uncertain.

“If they’re (the public schools) not reaching out in a timely manner, you should be giving them a call,” Schmeling says.

To help, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction in December contracted with WCRIS to serve as the state’s private school ombudsman to work with private and public school districts to monitor and enforce Title services.

“The hope is that through good education and collaboration, we can help prevent disputes by educating the private schools on what they’re entitled to and also working with DPI to educate the public school districts,” Schmeling says.

Another idea is to create a system of portability in Title programs, in which the funding follows each student. Currently, the amount of Title I funding, the largest Title program, is assigned to a school based on its percentage of low-income students. Under a portability concept, funding would accompany the individual student, regardless of which school the student attends. This “financial backpack” option was proposed for the federal Every Student Succeeds Act but was removed before its passage in December 2015.

Portability proponents say it would reduce state and district-level administrative burdens, fix school funding inequities caused by Title I regulations and create competitive incentives for schools to better serve kids. Opponents say it would sap much-needed dollars from poorer public schools and give them to students to attend private schools or public schools in wealthier neighborhoods.

Lauren Beckmann, principal of St. Robert’s Grade School in Shorewood says the federal funding system leaves some children out.

“I understand the formula and limits to funding, but it feels like it’s not in the best interest of our students,” she says.

Julie Grace, a graduate student studying communications at Marquette University, is an intern at the Badger Institute.

► Read the survey