Innovative, unconventional — and inexplicably made to operate on 60% of what other public schools get

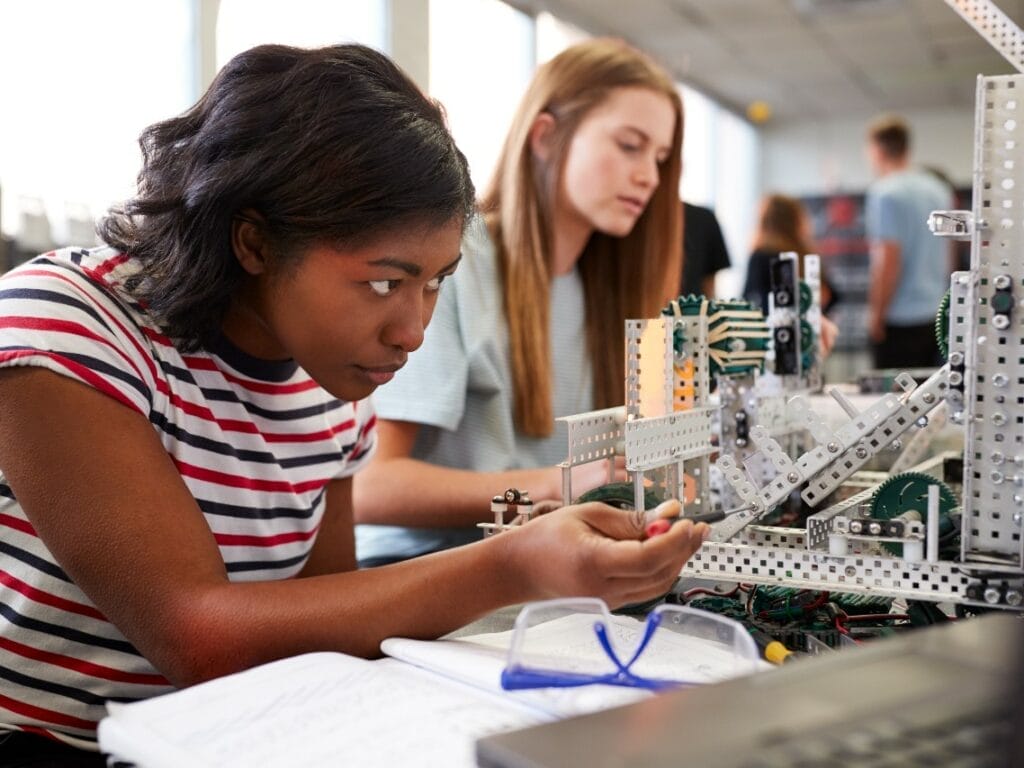

As you watch four kids in a low-ceilinged basement space soldering parts for the underwater robots they’re building, a teacher stopping in but not directing everything, it strikes you that this does not look much like a public high school.

But Pathways High School, on Milwaukee’s near west side, is a public school, despite appearances and vibe.

It’s just that, as an independent public charter school, Pathways is in the part of Wisconsin public education that’s underfunded.

It’s also in the innovative part, the unconventional part.

“Typical education, typical school is very linear,” said Franz Meyer, whose title, “impact director,” defies linearity. “At Pathways, that’s not how we work.”

Everything’s a project: “Kids come to a class, and we say, ‘What is compelling about this topic to you and how are you going to make it relevant? What is the product that you’re going to make around this thing, around this concept?’”

Electrifying a motorcycle becomes science and math and social studies lessons, with feedback from Harley-Davidson engineers. There’s a murals project where kids work with community groups. Meyer describes one project with an environmental nonprofit, Milwaukee Water Commons, where students scaled its Branch Out Milwaukee tree-planting campaign to small vacant lots.

“A lot of things in our culture today are focused on, like, what do you individually want?” he said. “What we’re asking our kids to do is think about how do you create the community that you want to be a part of.”

“This school really supports self-advocacy,” said Mariel Vang, who is in her first year as a high-schooler, “so if you want something to happen, you tell teachers. You communicate and collaborate with other students. … And if you have a good plan, it works out, it will happen.”

And if not, it’s try, try again, because figuring out what didn’t work is part of learning. Students were bustling around because it was Exhibition Day, a thrice-yearly chance to show projects to family and community. At other times, students must present a defense — bringing their work for critique by outside experts, such as those Harley engineers. Students are not necessarily expected to pass. They are expected to learn from the critique, to use it to master the material.

And to master adult life: Meyer’s title refers to the school’s “impact year,” an optional fifth year not meant as remediation but as a chance to take college classes for free at the school’s charterer, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, or at Milwaukee Area Technical College, while being coached on how to thrive in college. “A guided onramp to adulthood,” Meyer called it.

The school was founded by four parents, said Julia Burns, one of them, “who believe strongly that potential is being squandered in traditional public schools.” They wanted personalization, one-on-one instruction, creativity. When they approached a school district about chartering them, they were told it wouldn’t work, so they went independent, becoming a public school independent of any district.

And it does work after all. Pathways now dwells in a former church on Wisconsin Avenue — a statue of Jesus had to come off the front, since it is a public school — so, besides the classroom building, there’s vast space in what is now called “the great hall” where students were moving around displays for Exhibition Day. One kid strolls with a guitar, polishing a Beethoven motif.

It works, all the moving and doing, the mix of children from the central city and Wauwatosa’s Highlands, 22% with some sort of special education need. According to Burns, Pathways High students with disabilities performed better than 94% of the students with disabilities in the state in the 2021-2022 school year.

It works, not putting square pegs into round holes but getting children to calculate the precise shape of hole to make.

“One of my boys, who is the hardest sell when it comes to school or anything educational or traditional,” said Beata Abraham, mother of two students, “he came home, and he said to me something that brought tears to my eyes. He said, ‘I feel like they get me here and they let me be who I am.’”

It all works — provided the fundraising keeps up.

The school, a public school, gets $9,200 per pupil from taxpayers, the funding Wisconsin offers to all charter schools. There is no additional funding for facilities. By contrast, the average district public school in Wisconsin spends about $15,300 per child, the latest “total education cost,” according to the Department of Public Instruction.

Why the gap?

“The interesting thing about that is people think, ‘Well, you can survive on that because you might have less compliance, or you might have less overhead,’” said Kim Taylor, Pathways’ director. “None of those things are true. In charter schools, there’s actually much more oversight and much more compliance.”

It just has to happen with about 60% as much money as other public schools. This makes no sense. And it puts a limit on how many Wisconsin children can access such a personalized education, how many educators can offer one.

“Until we get to funding parity that is the same as what district schools would get, we’ll constantly be playing catch-up,” said Burns.

“In order for more schools like Pathways High, more innovative models that address the needs of diverse students, the state Legislature needs to get to funding parity for these schools. Bottom line.”

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields