UW-Madison finally grappling with how to tell the real story of its odious one-time leader

For years, I’ve wondered when and how the University of Wisconsin-Madison would deal with the odious history of its one-time president, the progressive icon with a building named after him on the campus, Charles Van Hise.

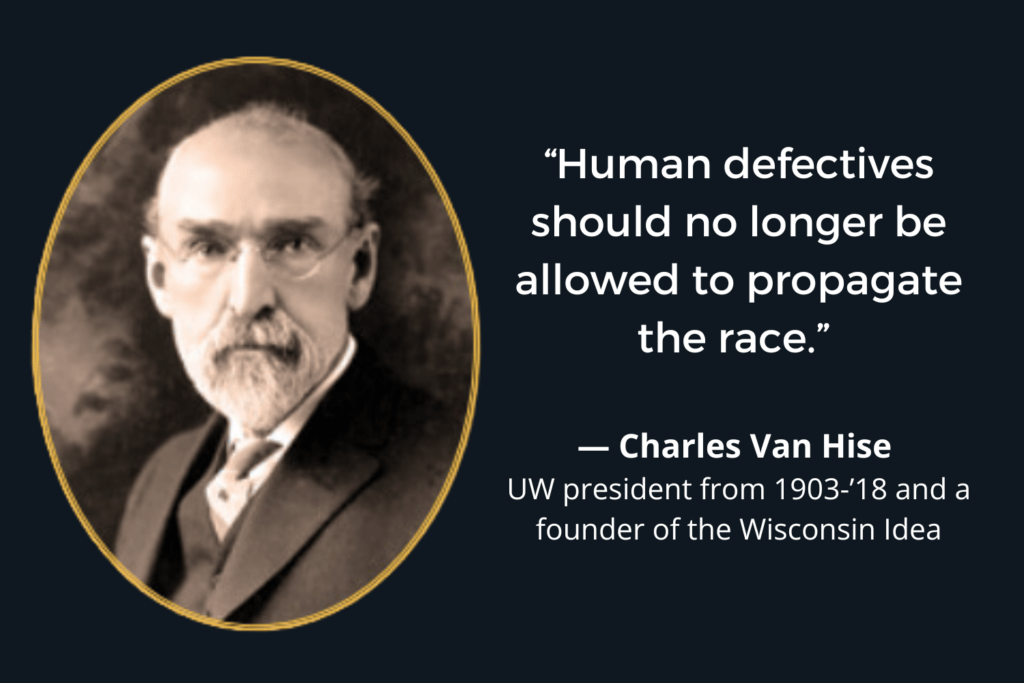

Van Hise was a eugenicist who wanted to rid the “race” of “defectives” so that future humans could have a “godlike destiny.”

“Human defectives should no longer be allowed to propagate the race,” he wrote in an essay, “The Conservation of Natural Resources in the United States,” published in 1910. “We should reach at least as high a plane with reference to human beings as with the defective animals.”

Years after Van Hise’s views were widely publicized, some at UW-Madison are apparently pondering whether to put up a plaque acknowledging the truth.

As Princeton’s Thomas Leonard, author of “Illiberal Reformers,” wrote in a piece for us here at the Badger Institute in 2016, Van Hise advocated for everything from involuntary sterilization to segregation in asylums or other institutions.

The UW-Madison president, according to Leonard, told a group of Philadelphians visiting Madison in 1913 that “we know enough about eugenics so that if that knowledge were applied, the defective classes would disappear within a generation.”

“Inspired by the slogan ‘sterilization or racial disaster,’ Wisconsin passed a forcible sterilization law in 1913, with the support of the University of Wisconsin’s most influential scholars, among them President Charles Van Hise and Edward A. Ross,” Leonard wrote.

Ross was an overt racist who, along with Van Hise, also pushed a so-called marriage statute. Together, according to a history posted on UW-Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences / School of Medicine and Public Health page, the laws authorized “involuntary sterilization of inmates of mental and penal institutions, and (required) verification that both parties to a marriage were not ‘epileptic, insane, or idiotic,’ nor carrying venereal disease — syphilis was assumed to be a disease of ‘degeneracy’ carried by the poor, foreign immigrants, African Americans, and otherwise marginalized people.”

Wisconsin sterilized around 1,823 “wayward, criminal, or defective” individuals from 1913 until 1963, 79% of whom were women, according to the same source.

Van Hise died in 1918 after a minor surgery, and Van Hise Hall was built shortly after the last Wisconsinites were forcibly sterilized by the state in the late 1960s. Like many of his progressive colleagues, he was anti-individualistic.

“Each should desire only what is right, and right must be defined as that which is best for the future of the race. In short, the period in which individualism was patriotism in this country has passed by; and the time has come when individualism must become subordinate to responsibility to the many,” he wrote in his “Conservation of Natural Resources” essay.

Referring to the Civil War, he wrote, “In the days of ’61 to ’65, a million men laid aside their personal desires, and surrendered their individualism for the good of the nation. Now, it is demanded that every citizen shall surrender his individualism not for four years, but for life — that he shall think not only of himself and his family, but of his neighbors and especially of the unnumbered generations that are to follow.”

It’s unclear what any plaque might say or whether one even will be installed. But The Daily Cardinal reported last February that a university Shared Governance Committee on Disability Access & Inclusion (CDAI) planned to propose placing a plaque in Van Hise Hall.

The paper reported that the plaque would need to be approved by both the UW-Madison chancellor and the UW system’s board of regents, among others.

Questions submitted Tuesday to university staff and a member of the CDAI committee were not answered by our deadline, so it’s unclear how far along they are in the process, what the plaque might say or how large it might be — though the answer to that last question seems obvious.

It should be large enough to tell the whole story of Van Hise’s abhorrent views and how the renowned progressive leader with utter faith in state government and its experts, but none at all in ordinary individual citizens, came to have them.

The man who spent part of his life trying to eradicate the freedoms and desires and plans of others, ironically, arrogantly pushed to impose his own “expert” opinions on the rest of Wisconsin — and he apparently was not one to take kindly to any dissent.

The “demand for transformation of the ideals of the individual, who has felt himself free to do with what he has as he pleases, to social responsibility, will be as great a change of heart as has ever been demanded by seer or prophet,” wrote Van Hise.

It’s unclear whether Van Hise saw himself as such a seer or prophet — though it certainly seemed so.

Van Hise went on in the same essay to promise that “the demand will be pressed in upon each man that he shall surrender his individualism as far as is necessary for the good of the race.”

As part of the cautionary tale of how arrogant “experts” can hypocritically push for collectivism or communalism as a way of thwarting the rights and freedoms of others — even to the extent of trying to literally eradicate them from the earth — that quote should be on the big plaque too.

Mike Nichols is the President of the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields