Dane and Waukesha counties embody the bitter partisan divide in the nation

By Torben Lütjen

Editor’s note: How is it that American political parties, for so long shifting coalitions of interests, have become more ideological than the ideology-based parties of western Europe? That question brought German political scientist Torben Lütjen to the battleground of Wisconsin politics.

Lütjen, who teaches at the University of Düsseldorf and is a visiting scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is researching a book on the reasons behind political polarization. He’s concluded that of the more than 3,000 counties in the United States, Waukesha and Dane counties best showcase the realities of polarization. Wisconsin Interest is pleased to offer his preliminary observations.

Few people could be more poles apart than bloggers Lisa Mux and David Blaska.

Mux is a liberal from Waukesha County, which encompasses the western suburbs of Milwaukee. The conservative Blaska is based in the state capital of Madison. Mux thinks about moving to Canada or Germany for what she believes is their superior health care.

Blaska is convinced that “Obamacare,” which in most European countries would not qualify as a large-scale “government-run” social program, means just another step toward “socialism” — a word that he never hesitates to use when describing the policies of the Democratic Party.

Blaska blogs at ibmadison.com. He says that what he enjoys most about his writing is the heat and the controversy, especially when he antagonizes liberals. Mux blogs at bloggingblue.com. She doesn’t like conflict and is shocked by the hatred that often characterizes political debate.

Blaska, apparently, is from Mars, Mux from Venus.

Still, they have something in common, and it was Blaska who put me on to it. “There is someone in Waukesha,” he told me over lunch in March 2012, “that is just like me.”

What he meant was that Mux is part of a local minority just as he is. She is a liberal voice in the conservative heartland of Waukesha County, just as Blaska is a conservative voice in liberal Madison. They share the same fate of belonging to a somewhat exotic species of people who seem to have picked a strange place for their fight and mission.

Madison’s position as the center of liberalism and progressive politics in Wisconsin is hardly a secret; when conservatives call it Mad City or refer to it as “70 square miles surrounded by reality,” it is not with affection. Waukesha’s public recognition as the bedrock of the Republican Party is probably a more recent phenomenon, and liberals have their own choice nicknames for it. “Mordor,” referring to the burned wasteland from which all evil springs in J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic tale The Lord of the Rings, is perhaps the most memorable one I came across, except maybe for the somewhat more precise formulation of “Mordor with lawns.”

All of this wouldn’t be overly important if not for the fact that today there are many Waukeshas and Madisons in the United States: places that have become heavy strongholds for one party or the other. We owe much of that insight to Austin, Texas-based journalist Bill Bishop and his 2008 book, The Big Sort. In 1976, Bishop writes, just about 25 percent of Americans lived in counties where the winner of the presidential election won by a margin of more than 20 percent. In 2004, the number of Americans living in such “landslide counties” had basically doubled.

Forget the simple red states versus blue states map that is broadcast during presidential campaigns, showing a liberal America in the coastal regions and a conservative America basically everywhere else. This map is, of course, an oversimplification. States are huge, and even within heavily blue states, there are deeply red patches, and vice versa.

Where America is really segregated is in much smaller units: counties, communities and neighborhoods. And Wisconsin, this once so widely praised example of political consensus and a civil political culture, is a perfect example. In the recall election of 2012, 70 percent of all Wisconsinites lived in counties that qualify as “landslide counties.”

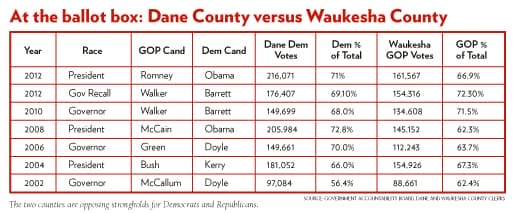

To put it in a nutshell: Three in four Wisconsinites reside in communities where one party dominates overwhelmingly and where the chances that their neighbors and colleagues share their worldview are very high. Unsurprisingly, Dane and Waukesha counties are leading the way here, too: Waukesha County went 72 percent for Scott Walker; Dane County, the epicenter of the anti-Walker protests, went 69 percent for his Democratic opponent, Tom Barrett.

Then again, why should it matter that the United States in general and Wisconsin in particular have become places of political strongholds? Why should we not be surrounded by those who mostly agree with us and turn our backs on those who hold opinions that we find, at best, painfully wrong? Why suffer from high blood pressure when we have the chance to live our lives untroubled?

It probably matters a great deal. A lot of evidence suggests that exposure to different viewpoints is essential to a healthy, functioning democracy. People who are subject to dissent, who are from time to time challenged in their beliefs, are simply more likely to take other positions more seriously.

Dissonant information creates ambiguity and ambivalence, and it makes us more aware that other viewpoints, as false as they appear to us, are no less (and sometimes no more) the product of human reasoning than our own. It definitely does not follow that we have to subscribe to the somewhat postmodern idea that, as a consequence, all ideas must be regarded as only “relatively” true or false; some reasoning can still be sounder than other.

But acknowledging that these ideas nevertheless stem from reasoning and that they are the product of specific experiences makes it harder to simply debunk them as either totally irrelevant or just downright evil.

There is reason to believe that America has become such a hotbed of ideological polarization because that kind of cross-cutting exposure is missing, and that the country has split into closed and radically separated enclaves that follow their own constructions of reality. This is true not only in the virtual world of partisan media but also here, in the physical world.

And when I say that without deliberation and dissent, we are in danger of perceiving the other side as evil, I am really speaking of a moral conceptualization of the political that partisans on both sides have now deeply internalized.

I remember a conversation with the owner of a popular bar on State Street in Madison — one of the places where the liberal heart of the Capitol beats — who told me about his drive to Milwaukee. It was right in the middle of the recall campaign. He had to drive through Waukesha County, became tired and pulled over. Suddenly he noticed all the “Stand with Walker” signs that were totally absent in his hometown. Before that moment, he had never paid much attention to the hill-after-hill suburban sprawl that is Waukesha County. And then he told me, more serious than joking, something that I think perfectly reveals the nature of the divide: “I felt dirty. When I had arrived in Milwaukee, I wanted to take a shower.” His feet had not even touched Waukesha soil (and never had before, as he frankly admitted), but he nevertheless felt “contaminated” by what he perceived as an alien, strange and even immoral place.

I heard such statements (this one clearly was the most stark) quite frequently when I talked to ordinary residents and political activists in both counties. Polarization is not only a consequence of deep divides over policy. In this case it was more a question of finding the other side bizarre and abnormal because of their lifestyles, the way they dress and speak, their tastes and their preferences. These are things not seemingly related to politics, but they are important for defining personal identity.

Yet, despite their profound estrangement, Dane and Waukesha counties, whose borders are merely 30 miles apart and separated only by sparsely populated Jefferson County, are not that different at all In terms of their demographics. Both are affluent, educated and predominantly white.

Most of the characteristics that helped us in the past to understand different political attitudes and ideologies do not contribute very much to explaining the depth of the division between Waukesha and Dane counties. And still, everybody visiting both places can see immediately how different they really are.

We may even leave aside the many stereotypes that nowadays are connected to the debate about the two Americas, although I do indeed suppose that the proportion of latte-drinking, New-York-Times-reading soccer-fans in Madison is higher than in Waukesha, which might in fact have a larger share of beer-drinking, country-music-listening NASCAR-enthusiasts.

More essential is the fact that life in these two places simply follows a different rhythm because of the way that public and private spaces are structured and interwoven with each other. In Madison, bikers and bike paths are everywhere, and if it were the only American city you ever visited, you would think that at least a fifth of all Americans drive hybrid cars.

In Waukesha County, SUVs and trucks are king, and seeing a cyclist must be a rare event, since I didn’t see one over a four-week period. Madison is densely populated, and many of its neighborhoods have their own centers with local stores, bars and restaurants. In the midsize cities of Waukesha County, such as Brookfield and New Berlin, a city center is absent, and I suspect not missed by its residents.

The only town with an urban setting is the City of Waukesha, the county seat and the only spot in Waukesha County where Democrats are close to competitive. James Wigderson, a conservative blogger who lives in the seemingly placid City of Waukesha, told me how other county residents don’t like coming downtown because they find the street system confusing and are afraid of getting lost. For those residents, the city is not a draw for shopping or entertainment.

When I told the legendary chairman of the Republican Party of Waukesha County, Don Taylor, a banking executive whose Waukesha State Bank is located in the middle of the city, that downtown Waukesha, with its cafés, art galleries and even one tattoo parlor, was similar to Madison, he replied: “Is that really true? Then it’s good I never go there, I guess!”

The truth is that the spatial structuring of a place is never an apolitical issue. It is the reason why land use is one the most debated issues in local politics and definitely the one that seems most illuminating to me in understanding the worldview of the cultural-political majority in each county.

Madison’s liberal political leaders love density. Much of their anti-sprawl attitude stems from serious and honest concerns about the environment. But it also follows an aesthetic ideal of a lively, vibrant city in which working and living are not so strictly separated, where people meet in public spaces and use public transportation and where real diversity can be found (although Madison, like every other hipster’s paradise, is in many ways one of the most homogeneous places imaginable).

No wonder that the creation of a light-rail system is a continuing dream of liberals in Madison, albeit one that seems not very realistic. In conversations I had with Madison liberals, Waukesha often served as the prime example of the negative consequences of unrestricted growth. It was hard to sort out in their criticism the line between policy disagreement and their subjective rejection of the suburban way of life.

“You can build whatever you want there,” a liberal member of the Dane County Board groused. “In suburbia, everybody is the same and nothing ever happens.”

Of course, residents of Waukesha County interpret their lifestyle as the exact opposite of uniformity: a celebration of American individualism. The many freeways and highways cutting through the county and the still remarkably dynamic development of subdivisions and yet another shopping mall are not only taken as proof of economic success but also as an affirmation of an individualistic lifestyle that offers both a maximum of freedom and a minimum of stress and inconvenience.

It is not surprising that sociologists have found that spatial configuration can deeply shape people’s attitudes about the way society should be organized. Whereas dense, urban environments often support the idea of togetherness and create a stronger awareness of how the interests of citizens — even when they are complete strangers — are intertwined, lower density/suburban environments support a more individualistic mindset.

It’s almost needless to say that the former experience creates higher support for the welfare state than the latter, even among those who are not direct beneficiaries of transfer payments.

Given the presence of the large university, the high number of state employees and Madison’s long tradition of being a laboratory of progressive politics, the city’s liberal leaning is self-evident and something of a self-perpetuating phenomenon for more than 100 years. Waukesha County’s conservatism, by contrast, is not only a more recent phenomenon, but seems also more in need of an explanation.

There are many possible reasons. But one thing that is specific about Waukesha County is its difficult relationship with Milwaukee, a relationship that is filled with extraordinary and mutual animosities. This city versus suburbia conflict is nothing special and can be found elsewhere. But there is reason to believe that this one is even more complicated, not only because Milwaukee is one of the most segregated cities in the United States with a long list of social problems that frighten suburbanites.

What is more important, I suppose, is that suburban Waukesha County is not the typical residential area from which people commute to the big city for work. Waukesha County’s economic success has transformed it into a politically and culturally exceptional place. Home to many small businesses, the county itself now supplies many of the jobs for its residents.

Driving I-94 during rush hour, one is surprised to see that there is actually heavy traffic in both directions, and in this case, intuition is supported by the data: Almost as many people now commute from Milwaukee to Waukesha County as the other way around. The extremely negative attitude that many people in Waukesha County have about the city of Milwaukee might, after all, be rooted in the fact that many of them lack any connection to the city itself.

The structure of a place cannot only shape political attitudes. It can also attract very different kinds of people, and I think that is what happened, too, over the last decades, as Waukesha and Dane counties appealed to different people from very different places.

It is important to note that both exhibit an extraordinary population dynamic: Many moved away; and even more — many more — moved in. This movement can by analyzed by using the data of the Internal Revenue Service, which tracks the migration patterns of Americans, or at least of those who file tax returns (which means the data encompass roughly 87 percent of the adult population). The patterns of migration that we find here are very different.

In the last 20 years, more than 85 percent of those who moved to Waukesha County came from a different county within Wisconsin, making out-of-state migration an insignificant factor. That most of the migration comes from Milwaukee is also not unanticipated.

However, the number of migrants from Milwaukee County is still impressive: Between 1990 and 2010, when much of the flight to the suburbs had already happened, more than 184,000 people moved from Milwaukee County to Waukesha County, accounting for more than half the total migration to Waukesha County.

Dane County’s migration pattern is a very different story: More than 40 percent of its new residents came from outside Wisconsin. Keep in mind that this does not involve the large student population, since most students do not file tax returns. The leading county from which Dane draws its new residents outside Wisconsin is Cook County, Ill., home of Chicago and one of the most populous counties in the United States. Given its proximity, that’s not a big surprise.

However, other counties over the years that rank high in out-of-state migration to Dane County are maybe more telling: King County, Wash.; Alameda County, Calif.; Middlesex County, Mass. These are also heavily populated counties, so maybe the migration to Madison is not out of the ordinary. But these are also heavy Democratic strongholds or “landslide counties” — affluent, highly educated and mostly located in the fastest growing parts of the nation. In short, Dane County gets many of its new residents from other “blue” counties whose demographic structures are similar to its own.

There is, I believe, indeed an element of residential segregation that explains how these places have become increasingly homogeneous. Certainly, people do not consult an election atlas to find out where they can mingle with other partisans. The “big sort” is more driven by lifestyle choices and tastes and preferences than by concrete policy issues.

Having spent several months in both Dane and Waukesha counties, I didn’t really need the numbers to know that this “sort” was happening, and more importantly, that it is likely to continue.

It was sufficient to talk to those who stand in opposition to the local majorities. True, some are natural contrarians who love going against the grain, who love being the troublemaker and who say that they wouldn’t want to live in a community where everybody thinks just like them. And I met others who dislike the political philosophy of their place but say that it seldom affects their everyday lives because they just avoid talking politics.

But many more, according to my impression, do indeed feel isolated, not taken seriously, and frustrated by what they perceived as the ignorance of those who hold power. And ignorance is not the worst of it.

I heard harassment stories that range from subtle social pressure to downright mobbing. These were people who told me that their cars were keyed because of Republican bumper stickers or who complained that their campaign signs were stolen by their neighbors. Every so often, it was hard to tell where harassment ended and paranoia began.

Some stories, though, bordered on hilarious. The leader of the Republican Party of Dane County tried during the first months of his chairmanship to keep his name out of the media for fear it would hurt his business. How he expected to publicly represent the party wasn’t exactly clear, and he became known as the “secret GOP chair.”

It seems, finally, like a vicious circle: Homogeneous places like Waukesha and Dane counties pressure political “minorities” — subtly or crudely — into silence and into retreat from public life. These outliers sometimes give up and just want to get away from a community where they feel reviled for their opinions. That decision, however, makes these places even more homogeneous — and so the cycle continues.

No wonder American politicians have become more extreme and less willing to compromise. Many of them are sent to Madison or Washington, D.C., by voters who live in an echo chamber and cannot imagine contrary viewpoints worthy of consideration. In such a climate, every compromise is deemed a weakness and surrender, when in fact compromise is what politics is all about.

So I conclude: As Waukesha and Dane counties drift apart, so does the nation.

SOURCES: U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY ESTIMATES, 2006-10

SOURCE: GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY BOARD, DANE AND WAUKESHA COUNTY CLERKS

The two counties are opposing strongholds for Democrats and Republicans.

Lütjen runs a research group in Düsseldorf funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. He has authored several biographies and writes essays for major German newspapers. He is currently a visiting scholar at UW-Madison.