By Mike Nichols

Research Assistance by Christian Schneider

Long before he became a prominent, well-paid lobbyist skilled in influencing lawmakers and helping direct big contributions to their campaign funds, Marty Schreiber was the acting governor of Wisconsin. He was also the person who, on Oct.

11, 1977, signed into law what was then known as Assembly Bill 664.

Only 38 at the time, the young governor was unabashedly giddy as he praised the legislation setting up the new Wisconsin Election Campaign Fund.

The new system of taxpayer-financed campaigns, he gushed in a letter to legislators, was “the most significant political reform measure implemented in Wisconsin since the Progressive reforms of the turn of the century.”

Supported by a $1 check-off on state tax forms, the fund was meant to supplant campaign donations to candidates from political action committees, ensure those of modest means had money to run and prompt “more competitive races.”

Stating that the day was “long past when candidates should be allowed to buy elections,” Schreiber also lauded new spending limits that, as the result of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling Buckley v. Valeo a year earlier, could be

imposed in races that included the public dollars.

The campaign fund was, in short, going to “fundamentally [alter] Wisconsin’s political system.”

And today?

The fund is, in the words of one elections observer, “dead as a doornail.” Legislators recently voted to fund Supreme Court races through a new “Democracy Trust Fund,” but the separate fund set up in 1977 still exists for everybody else, and dozens of candidates still take the taxpayer money.

Yet it does nothing to limit spending or promote competition and little, at best, to limit special interest involvement.

Thirty years after Schreiber’s paean to publicly financed campaigns, the fund hasn’t just failed to live up to its authors’ vision. It has, in fundamental ways, helped undermine it.

And still—despite the recent suggestion of the state’s most prominent elections expert, Government Accountability Board Director Kevin Kennedy, that legislators just get rid of the campaign subsidy—it has persisted in draining more than $1.3 million from the state’s general fund since 2002.

Marty Schreiber wasn’t the sole architect of publicly funded campaigns. The initial draft listed no fewer than 50 bipartisan sponsors, including a future mayor

of Milwaukee, John Norquist; two future governors, Tommy Thompson and Scott McCallum; a future congressman, Tom Petri; and a future ambassador, Tom Loftus.

It was Schreiber, though, using his so-called Frankenstein veto to cross out

words and sentences, who decided to fund it through the check-off that gave taxpayers the ability to direct their tax dollars out of the state’s general coffers to candidates.

Today, an analysis by Wisconsin Interest shows that virtually the only people who use the fund are either Assembly-seat challengers who have no chance of winning or incumbents in safe seats.

True to the original intent of the bill, challengers use the money about twice as often as incumbents, but they almost never prevail. And when they do there is little evidence it has anything to do with the use of tax dollars. Of the 129 challengers taking grants since 2002, only six have defeated sitting incumbents, and all of them did so in races with no spending limits.

Those spending limits that Schreiber extolled only come into play when both candidates accept public funding-–and nowadays that never happens. Of the 26 candidates who took taxpayer money in 2008, not one had an opponent who also used public dollars.

Schreiber’s vision of a lasting reform that would limit spending was, the statistic suggests, a pipedream—as was his vision of unfettered, real competition. Challengers who have taken the grant in recent years haven’t just lost. They’ve been pulverized.

Since 2002, the average vote for the 126 losers who accepted a grant was a paltry 39%. Mike McCabe, executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign and the man who labels the fund dead as a doornail, resists the conclusion that Schreiber’s vision was doomed from the start.

“It did pretty much live up to its billing for a decade,” he said. “It worked well for 10 years, and it can again.”

McCabe, a tireless advocate of public financing, notes that the $1 check-off was never adjusted for inflation. Grant amounts and spending limits that were adjusted initially have, meanwhile, been frozen since the late 1980s. Public financing, he says, simply

isn’t ample enough to be meaningful.

For example, today, Assembly candidates can receive no more than $7,760 and, when limits are imposed, spend only $17,250—about a third of what is usually burned through in relatively competitive districts.

Senate candidates can receive up to $15,525 in public financing and, when limits are imposed, spend only $34,500.

Candidates for governor can receive up to $485,000 in public money, and spend about $1.1 million-–a pittance compared to the $32 million spent by Jim Doyle and Mark Green and outside interests in the 2006 gubernatorial election. The last gubernatorial candidate to take the money was Ed Garvey, who was blown away by Tommy Thompson in 1998.

It is “suicide” for candidates to accept the spending limits, says McCabe.

The low spending limits “killed public finance,” according to Gail Shea, a former Elections Board official.

Raising the spending caps among other proposed changes (for example, publicly funding state Supreme Court races, which the high court supports) could do much to save the program, advocates say. More and bigger public financing, the implication is, would help combat all the problems Schreiber wanted to solve.

A closer look at the history of the public fund suggests, then again, that expansion might only worsen them.

One of the things Marty Schreiber wanted to avoid was the specter of incumbents taking money from taxpayers while stocking their war chests for future campaigns.

“It is contrary to the intent of this bill to allow public funds to be used to build campaign surpluses,” Schreiber said in his veto message. “Furthermore, such a policy depletes the fund.”

He tried to make sure that “if a candidate received a $2,000 grant and had $3,000 left in his treasury after the campaign, he would return $2,000” to the fund.

Tax dollars taken from the fund by candidates have always had to be spent on

specific things like printing or ads—or returned. Even if the tax dollars were

properly spent, however, candidates in the early years had to repay the fund,

i.e. taxpayers, with their private donations if they had cash left over at the end

of a campaign.

Candidates didn’t like that, and elections administrators didn’t particularly like chasing them for the refunds.

To get more people to use the fund and accept spending limits (or perhaps just to give the upper hand to incumbents), a change was made. In 1985, then Sen. Lynn Adelman introduced an amendment that separated the taxpayer dollars from the private donations candidates collected-–something that Schreiber had feared would allow candidates to “use public funds to build campaign surpluses” through

“subterfuge.”

It was a prescient fear. After the amendment was adopted in 1985, candidates were free to spend tax dollars on ads or pencils and either save private contributions for their war chest or give them to somebody else—exactly what some bigger

fundraisers have done since.

Spencer Black, the longtime Democratic representative from Madison, has repeatedly taken the public subsidy while building up big surpluses in his campaign account. First elected to the Assembly in 1984, Black has been reelected a dozen times. Up until 2000 (when opponents just gave up and stopped running against him), he applied for the tax dollars almost every time he ran.

Records from the first few elections have been lost by the state, but he was given more than $18,000 in taxpayer dollars in 1992, 1994 and 1996 alone, according

to the Government Accountability Board (GAB). Those were years in which Black

built his campaign fund up from a surplus of $39,000 in 1992 to more than $100,000 by 1997.

Adelman, now a federal judge, declined to comment on his long-ago amendment. The GAB’s Kennedy says that the change reflected “the practical realities of keeping the fund viable.”

It was also, of course, counter to Schreiber’s founding vision—and not just in Black’s case. Black, who didn’t return calls from Wisconsin Interest, is far from alone in using tax dollars to campaign while using private donations for other things.

State Rep. Gordon Hintz of Oshkosh took more than $19,000 from the fund for races in 2004, 2006 and 2008 and ended his last campaign with a surplus close to $40,000. The Democrat has never had to comply with spending limits because his Republican opponents have always declined the money.

Indeed, Republicans take about one-fourth of the public funding that Democrats accept.

“I never check it off on my income taxes, and I don’t believe the government should be involved in funding any campaign,” said Julie Leschke, whom Hintz defeated in 2006. “In my opinion, it’s not ever a wise use of tax dollars. It’s too distant from taxpayers.

Taxpayers have no knowledge of who gets it and how it is used.” Mark Reiff, the Republican whom Hintz steamrolled in 2008, raised another issue: “Do we really want the public to be funding everyone’s whack-job ideas?” Hintz, for his

part, acknowledges the system could work better. But he stressed that the public fund does accomplish something: Any candidate who takes the full amount of public money available is barred from taking PAC money.

“Anytime that we can reduce the perception that outside special interests have a disproportionate influence on things, the better it is,” Hintz argues.

Left unmentioned is the fact that significant limits on PAC money already are imposed on all candidates in Wisconsin, not just those who take public dollars.

(For instance, Assembly candidates can accept no more than $7,760 from PACs and candidate committees.)

The public fund, meanwhile, has no legal authority to regulate issue ads or independent expenditures that started to dramatically affect campaigns in the

late 1990s. Nor does it address another common phenomenon of modern politics: incumbents funneling their contributions to other politicians or campaign committees even as they accept public dollars.

Black, for example, received $4,155 from the public fund on Sept. 30, 1996. This is the same year he gave a total of $4,775 in cash or in-kind contributions to other politicians or committees, including $1,200 to the Dane County Conservation Alliance—a special interest committee registered with the state.

On Sept. 30, 2004, state Rep. Mark Pocan accepted $5,574 from the public fund. According to his campaign reports, on that very same day he made a $1,000 contribution to the Unity Fund—the Democratic Party of Wisconsin campaign account that was used, at least in part that year, to support Democratic candidates at the national level.

Hintz received his most recent public funding, about $6,000, on Sept. 27, 2008. In the month that followed, he gave $1,000 to the Democratic Party of Wisconsin.

Pocan pointed out that politicians do sometimes receive campaign help from their parties, and recalled that the Unity Fund payment provided him with things like voter identification and access to phone banks. A review of his 2004 campaign finance reports shows no evidence that he received anything of value

in exchange for the $1,000 that year, however. If he did, according to GAB rules, the payment should have been listed as an “expenditure” rather than the way it

was, as a “contribution.”

Public campaign dollars are “separate money,” Pocan also said when asked about the Unity Fund, and his contribution to the Democratic Party was, therefore, “not part of the $5,500” he took that same day from the state.

Still, the simultaneous funneling of money elsewhere raises fundamental questions about whether some politicians really need public dollars-–and whether their use of those dollars, instead of making the system more competitive, has helped make it more byzantine, more sophisticated and more of an insider’s game.

Politics in Wisconsin is, at the very least, not a game for outsiders. Spencer Black hasn’t received less than 87% of a vote since 1992 and now has more than $146,000 in his campaign account.

In 2002, Republican Steve Nass accepted $7,013 in public funding and went on to beat Leroy Watson 87% to 13%. In 2006, the Whitewater-area representative took $5,963 and beat a self-described “naturist,” Scott Woods, 66% to 34%.

The average vote for the 47 winners who have accepted money from the fund since 2002: 63%.

If the fund helps anyone, it seems, it is incumbents, the legislators who have the power to make the laws and amend them. Or get rid of them, but don’t.

Lawmakers did make some key changes to the public financing system after the caucus scandal in 2001. But the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign’s McCabe and others argue it was a mere charade that insiders knew would never pass constitutional muster in federal court-–and didn’t. Getting rid of the fund, in

the meantime, has also proved impossible.

Testifying before the Joint Finance Committee earlier this year, Kevin Kennedy—despite his personal belief that public funding has a role in modern campaigns— encouraged budget-cutting legislators to “examine the

viability of this program in its current state.”

“If you are looking to take money away from our agency,” he says he told them, paraphrasing his own comments, “why don’t you take this money?”

It never happened.

Mere talk of the U.S. Supreme Court possibly overturning key provisions of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance legislation is, instead, spurring discussion of renewed public financing at the state level.

Legislators have passed the so-called Impartial Justice Act—that increases the check-off to $3 and directs some of that money to the new “Democracy Trust Fund” for state Supreme Court candidates. At press time, Gov. Jim Doyle was expected to sign the bill.

The new fund for Supreme Court races differs significantly from the Wisconsin Election Campaign Fund—the check-off alone is unlikely to provide anywhere near the money Supreme Court candidates could qualify for, up to $1.2 million apiece.

Indeed, the percent of people checking the box on their income taxes has decreased from a high of 20% in 1979 to less than 5% in 2008. Check-off programs alone simply don’t produce much revenue, meaning legislators who want to increase public financing would have to find cash elsewhere—and lots of it.

Wisconsin taxpayers, as a result, might need to kick in millions from the state’s General Fund for a single contested state Supreme Court race under the Impartial Justice Act—and they would be doing it at a time when public support for taxpayer-financed campaigns has diminished. A 2006 Wisconsin Policy Research Institute poll found that 65% of Wisconsinites oppose using tax dollars to finance political campaigns.

Back in 1977, a different governor, Marty Schreiber, lauded the sort of public financing that would allow candidates to compete “without relying on huge special interest contributions.” In 1978, he put his money—or lack thereof—where his

mouth was.

Schreiber and Lee Dreyfus, his Republican opponent in the 1978 gubernatorial race, both accepted tax dollars to campaign and the spending limits that came with

them. Schreiber also got trounced.

He gives no hint of regret.

“If the question is, ‘Did I hoist myself on my own petard by developing a process of campaign financing?’” he says, “there are probably a hundred reasons I lost that campaign.”

He resists the suggestion he was “naïve” back in 1977, saying he would not use that term.

“Was I a dreamer?” he asks instead.

He answers his own question by saying that, back then, he wanted to find a way to ensure that everyone who wanted to compete could compete.

“I had never projected,” he adds, however, “that a 30-second TV ad would be what it is.”

Perhaps he never envisioned either what would become of Marty Schreiber himself—and how different he appears after a couple decades as a lobbyist.

In 1988, Schreiber launched Martin Schreiber & Associates, a successful “public affairs consulting” and lobbying business. He and other individuals affiliated with the firm have contributed more than $73,000 to candidates and various committees since 2000.

They do much more than that, though. The firm promises to help clients “coordinate

media campaigns” and develop and manage PACs and conduit funds, which are pooled contributions from individuals, to achieve a group’s political objectives.

At least two clients—the Forest County Potawatomi Community PAC and the Wisconsin Beverage Association PAC—list Schreiber & Associates employees as either the treasurer or assistant treasurer.

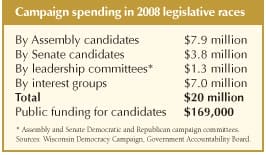

The impact of PACs, then again, often pales in comparison to money spent by so-called special interests elsewhere.

The Wisconsin Democracy Campaign notes, for instance, that the Potawatomi tribe reportedly funneled at least $1 million to the Greater Wisconsin Committee. The GWC, in turn, spent more than $4 million on issue ad activity that benefited Gov. Jim Doyle during the 2006 election.

Schreiber, for his part, declines to talk about the big-picture questions of whether the fund worked and can work again, whether it needs to be tweaked or discarded altogether. He simply says it is an issue he has not studied in some 30 years—a span of time in which campaigns have changed, perhaps, almost as much as Marty Schreiber himself.

Nowadays, Schreiber appears to question what the term “special interest” even means. “Anyone who has an interest different from anyone else’s has a special

interest,” he says.

Mark Reiff, like many Republicans, has come to the conclusion that “anyone who thinks they are going to keep special interest money out of politics is kidding

themselves.”

The best you can do is make sure everyone knows where money is coming from, and what it’s being spent on, he says.

After all, the U.S. Supreme Court is not inclined to quash the First Amendment rights of so-called special interests.

Perhaps the most lasting lesson of Schreiber’s grand experiment is this: Political campaigns are a complicated and unpredictable business, and noble efforts to reform them sometimes backfire or just plain fail to deliver on their high-minded promise.

At least until taxpayers, once and for all, stop checking off that little box.

Mike Nichols, whose columns appear in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel,

is a syndicated columnist and author.

Christian Schneider is a Senior Fellow at the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.