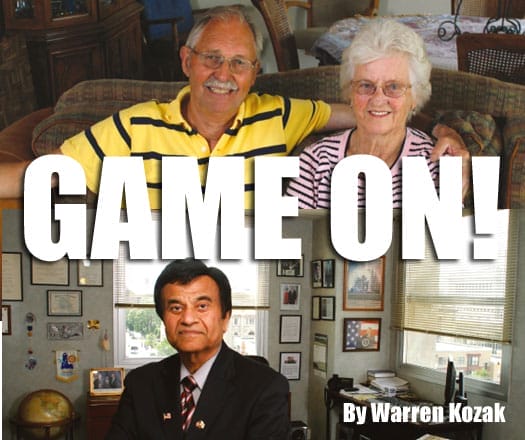

Immigrants like Peter Boscha and Yash Wadhwa understand that competition is the secret to American success

Here is one of life’s little mysteries: If you place two 4-year-olds in the middle of a block, they will, without prompting, immediately race each other to the corner. Michael Phelps never breaks records in the pool by himself. But line up five other swimmers next to him and Phelps smashes world times. And when two teenagers are idling at a red light, engines running and no cop in sight, it might be wise to get out of their way.

We see the impact of competition every minute of every day, yet few of us realize that the greatest consequence of competition has been its impact on the American economy. Competition has electrified it and pushed it past every other nation on earth. It can be as mundane as watching service improve and prices fall at your local grocery when a competitor opens up across the street. And it reaches to the highest echelons of American business — from Ford to Gates.

But as critical as competition is, few of us understand the first thing about it. We don’t know its origins, why it pushes us forward, why some people are more competitive than others or why artificial constraints on competition will stifle an entire population and leave an economy stagnant. To help explain all this, let’s look at two Wisconsin residents who have never met and come from very different worlds but who have one very important thing in common.

Peter Boscha was born in a small rural town in Holland in 1932. When the Nazis occupied his country, his education stopped at sixth grade. But Boscha had a dream that he could do more than work on a farm for the rest of his life. And he instinctively understood that his dream would not be fulfilled if he stayed in postwar Holland. So he took a chance and came to the United States with his girlfriend in the mid-1950s.

On the other side of the world and some years later, Yash Wadhwa had the same dream. Wadhwa was born in Delhi, India, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering. Like Boscha, Wadhwa knew that his native country did not offer the opportunities he desired.

After a series of grimy factory jobs, Peter Boscha learned how to build houses. He took a chance and bought some land, subdivided it, built homes and sold them. He developed a reputation for honest, good work, and he prospered in Racine. Wadhwa received an advanced degree here in the U.S. and took a job first in Buffalo, N.Y. In the early 1970s, he was transferred to Milwaukee, where today he is the head of Strand Engineering’s Milwaukee office, overseeing more than 100 employees.

Both men have raised families and been involved in their communities. Both men are considered success stories. And fulfilling one of this country’s truest beliefs in individualism, both men accomplished this on their own.

What Boscha and Wadhwa were defining, even though they may not have realized it at the time, was a reality that, on one level, is astoundingly simple. The United States — more than any other country in history — offers human beings the chance to express one of the most basic, even primitive human instincts, the chance to compete against others and the chance to win. Even though this concept sounds obvious, few nations throughout history have actually offered this common-sense equation to humankind.

Competition is innate in human beings. It comes naturally to us because it is in all of us. We are descended from hunter-gatherers who understood that if their tribe did not get the wooly mammoth before the other tribe, they would not eat and they would die. Males have always competed for the most desirable females. Darwin saw competition as a critical part of human evolution.

“Competition is a very powerful force,” said Patricia Tidwell, a psychoanalyst in New York who has studied competition, especially as it relates to females. “It causes us to perform better but it also gets us in the game. … It forces human beings to learn how to win and it ultimately makes people successful.”

We experience it throughout our lives. Whether it is on the playground or in basketball tournaments or comparing test scores in junior high school, these are lessons we learn early and ones that continue to play out through adulthood in work, business and personal relationships.

As a recent full page newspaper ad for Sprint reads, “Competition is the steady hand at our back, pushing us to faster, better, smarter, simpler, lighter, thinner, cooler.” Sprint should know. If it weren’t for the landmark court decision in 1984 that broke up the Bell System monopoly and allowed other phone companies to rise up and compete against each other, there would be no Sprint today — and we would be paying higher phone bills.

What motivates people like Boscha and Wadhwa to pick up and leave their homes for a far land where they don’t know the language or anything else? According to Tidwell, the first reason is a problem. “The very first people who came to America did so because they weren’t able to do what they wanted to do back there.”

For some, it was religion. For others, like Boscha and Wadhwa, it was opportunity. But the opportunities were not handed out at Ellis Island. These new immigrants had to learn everything from a new currency to laws and business practices before they could succeed. And up until the end of the 20th century, there were very few government or even private institutions to help them along the way.

But only a certain type of individual is willing and able to emigrate: a person with an adventurous streak and a competitive personality. And while they understand that in America, their chances of success were simply better than anywhere else in the world, they also know there is a catch. Success would be completely up to them. “If you are highly risk-averse,” said Tidwell, “you are not going to be a good competitor.”

Throughout history, there have been particular periods where thriving competition pushed people to do greater work. The Impressionists in the late 19th century learned from each other, but they were also competing with each other. The physicists in Germany and Hungary at the beginning of the 20th century were doing their own research, but they were all looking over their shoulders at each other, and everyone was watching Professor Einstein. The space race with the Soviets put Neil Armstrong on the moon within eight years of the first manned space launch.

But strangely, as human beings evolved and tribal societies matured into nation states, almost none of these man-created entities allowed for this very strong innate force to manifest itself in its natural way. In fact, they did the opposite. Barriers were set up through royalty, caste systems and variations on authoritarian rule — some benign, most not — that subverted free enterprise and competition. Thus, their natural potential could never be achieved.

The first person to formally recognize this and integrate it into an economic theory was an 18th century Scotsman named Adam Smith. Smith blended the two components, competition and economics, and in so doing had a profound effect on the future of the world. Smith’s lectures at Edinburgh were the framework for his book, The Wealth of Nations, first published in 1776.

In the same year, a group of men in Philadelphia designed another experiment called the United States. In this design, they opened up everyone and everything to compete through hard work and innovation.

It is for this reason alone that the U.S. gained some of its most profound and beloved leaders — men who came from extremely modest backgrounds. For every Roosevelt and Kennedy and Rockefeller that entered politics, there are many more Lincolns, Clintons, Ryans and Obamas. Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower were born on working farms.

Another example is the man who laid down the framework for our economic system, our first Secretary of the Treasury — Alexander Hamilton. Here was a man born to a prostitute, abandoned by his father in the Caribbean and left to his own very formidable devices. Hamilton rose through the ranks of the Continental Army, was noticed by Washington for his brilliance and daring, and was given huge responsibilities in the new government. He accomplished all of this without lineage — just sheer merit.

Such acts of self-definition are the stuff of the enduring American ethos. These are the Horatio Alger stories: the young men and women who come from nothing and eventually overcome great hardship and trial to become enormously successful. And of course, there are the immigrant stories that spread across the globe and created a self-fulfilling prophesy by fueling an even greater desire to go to America.

There are the classic immigrant stories such as those of Wadhwa and Boscha, and practically every family has one. They are our family stories, and you don’t have to go too far back to find them in your family tree.

When World War II ended, Peter Boscha was 13 years old and things had changed in his country. All of Europe, in Boscha’s mind, seemed to be self-limiting. America, on the other hand, seemed to be a place where his imagination could run wild. So Boscha began talking to his girlfriend, Linda, about leaving Holland for the United States.

Boscha still remembers the date and time of his redemption — it was a Saturday morning, at 11 o’clock. The mailman came to the door with one of the greatest gifts of his life: “The visa to the promised land.” That’s how Boscha still refers to the immigration papers that arrived from the U.S. Consulate.

On the other side of the world, Yash Wadhwa had the same dream. Wadhwa was well educated, getting a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering in Delhi. But throughout his adolescence, Wadhwa’s favorite activity was going to the American library in Delhi to read U.S. history books. He remembers the pictures of presidents up on the wall and would stare at them with awe. Just as it had to Boscha, this far off land seemed to beckon to Wadhwa. And like Boscha, Wadhwa recalls that in America, all things seemed possible — anything a person wanted to be, he could become.

In the late 1960s, India under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi moved closer to the Soviet Union. Rampant corruption, India’s crushing caste system and a multilayered government bureaucracy stifled business and competition. Like Boscha, Wadhwa’s parents were not happy about the idea of their son leaving home in search of new opportunity, but they also understood that the economic system in the U.S. offered him a better chance to maximize his potential. In 1969, Wadhwa enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh for an advanced degree in civil engineering and environmental engineering.

Both men adapted immediately to their new country, but they held on to important parts of their past. They married women from their home country — Boscha married Linda, and Wadhwa married Usha from his hometown. Wadhwa went directly upon graduation to a good job at the Larsen Engineering firm in Rochester, N.Y., in 1971.

He was transferred to Milwaukee eight years later. After 16 years at Larsen, he moved to Strand Engineering and is the head of its Milwaukee office and its 150 employees.

Boscha started at rock bottom — his first job was with J.I. Case in Racine in the late 1950s, where he hauled dyes and material on the factory floor. When an opening in the machine shop came up, he asked the foreman to consider him. When the foreman asked if he any experience, the bold young man simply replied, “Give me a chance and if I can’t do it, I’ll leave.” Boscha got the job.

Everything changed when Linda’s cousin needed a partner in his building business and offered Boscha the job. When Boscha went to his foreman and told him he was leaving, the foreman didn’t want to lose a good worker and told him he couldn’t go.

Boscha’s only comment was, “I didn’t come to this country to punch a time clock.” His boss looked at him and then leaned over and whispered: “You’re right. … Good choice.”

I asked various experts what impact competition has had on the U.S. economy. They all more or less agreed with Tidwell’s succinct definition: “It made it the dominant economy in the world. Period.” But she pointed out something that was equally important when I asked her if that was because competition was encouraged here in the U.S. “It’s not just that it is encouraged but that it is celebrated,” she said. And that comes across again and again in our national story.

As an example, Tidwell offers a man who sees someone else create widget number one. “He sees it and instead of just seeing a widget, he envisions an even better widget that can be made better and faster and cheaper. Basically, he thinks he can do it better and he wants his widget to beat the other guy’s widget.”

“Competition draws on people’s creativity,” observes Tidwell, “and that’s how things improve. Otherwise, everything would remain the same; there would be no advancement. Successful people figure out ways to win, and that is another example of how competition is directly tied to innovation.”

This is exactly how Peter Boscha moved from learning how to frame a house to the intricate business of buying land, subdividing it, dealing with town ordinances, building quality homes at affordable prices and selling them. Along the way, he also employed dozens of carpenters, plumbers and roofers. Yash Wadhwah had to figure out a way to beat other engineering firms bidding for contracts by providing it for less while still giving a quality product. “Competition,” says Wadhwa, “is everything. It is what causes us to do a better job for less.”

The positive side of this equation can be seen in the evolution from the A&P in the early 1900s to the Kohl’s Foods grocery chain following World War II to Costco and Sam’s Club today.

Practically every small town in Wisconsin had an A&P on its Main Street for the first half of the 20th century, and in most of these towns, it had a monopoly. After an Eastern European immigrant by the name of Max Kohl came to Wisconsin in the early part of the century, he introduced a more modern, better lit and larger store that was more pleasant to shop in. Produce, bakery and meats were fresher and better presented. Soon, Kohl’s surpassed the A&P.

Today, borrowing on that theme, stores like Costco and Sam’s Club offer customers even larger stores, broader selection and lower prices. In today’s challenging economy, that is what many customers desire. But all of these stores watched each other to improve and innovate. Throughout it all, the chief beneficiary has been the customer, although the heirs of A&P founder George Huntington Hartford, of Max Kohl and of Sam Walton did pretty well also.

Harry Truman once remarked that his job as president was, in many ways, far easier than when he was a young man working on his family’s farm. Even in the White House, Truman said, his greatest fear at night was imagining his father calling from downstairs at 4 in the morning to get up and start plowing. Here was the leader of the postwar free world, who faced down first Germany and Japan and then Stalin, yet he woke up worrying about the backbreaking work of running a horse-drawn plow.

But today that work ethic, once the standard, may not be pervasive. There are 44 million Americans who receive some form of food stamps. Unemployment benefits continue to be extended, which will cause some people to be less aggressive in their job hunts. The dirty factory job that Peter Boscha was glad to get when he first arrived in America was miserable work. But he learned something from it, and it gave him the opportunity to move up the ranks.

Certainty is the enemy of competition. This was made clear in the failure of the Soviet Union and most of the communist governments in the 20th century that sought to dominate the world economy: People do not work as hard when guaranteed an income. Human beings need incentives. “Why bother,” asked Tidwell, “if I get the same amount whether I work or not?”

Why indeed? But two decades after the fall of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites, some of those same practices have taken hold here in the United States. Union protection of jobs, teachers with tenure — jobs for life — and state workers with nearly free pensions work very differently than their neighbors who have to compete in the private sector.

Teachers, bus drivers, fire and police officers are very necessary and treasured parts of our society. But it is doubtful that the drive of a Henry Ford can be found within many in those ranks — the constant push for greater efficiency is just not there when a human being knows that his job will be there tomorrow no matter what. That “hand at your back, pushing us to faster, better, smarter” mentioned in the Sprint ad just isn’t there.

There have been critical points throughout this country’s history that changed everything thereafter. The Civil War, the Industrial Revolution, the Great Depression and World War II were four such periods. And we are living through one today.

One decade into this new century, Americans are no longer just competing with other Americans, they are in a flat-out sprint with billions of highly motivated human beings around the world who, for the first time, see the possibility of bettering their own lives. Globalization has driven our country and our world into hypercompetition.

So we stand at this divide and we hear the voices from our present and our past. If there is a force that could stifle competition and destroy what made this country productive, it comes from within. Americans have sometimes failed, but the mark of success is getting up and trying again.

When a 12-year-old loses a race, when a 15-year-old loses a soccer tournament, it might seem like the end of the world. It is, in reality, only the beginning. We often hear America compared to Rome — that the end of the empire is at hand. And there are leaders from our past — men such as Lincoln, Roosevelt and Reagan who had boundless optimism in this country, its potential and its future.

Peter Boscha and Yash Wadhwa heard this call in distant lands many years ago. Today, many years later, they believe in this country with all their hearts — and for good reason. America still has the most amazing toolbox ever assembled. It has a Constitution now in its 236th year and as fresh and strong as it was on its first day. It has a rule of law — not perfect, but as close as human beings have come to getting it right. It has spirit and charm and the awesome ability to renew and reinvent itself. And it has a competitive advantage that is still the envy the world.”

Warren Kozak is a former reporter for National Public Radio and has written for news anchors at ABC, CBS and CNN. His latest book is LeMay: The Life and Wars of General Curtis LeMay (Regnery, 2009). A longer version of this essay appears as a WPRI Report.