Editor’s note: Christian Schneider, a WPRI senior fellow, spent nearly a decade running campaigns in Wisconsin. This story was written over the span of six months and is the result of dozens of interviews with campaign staff, consultants and Ron Johnson himself.

The day after Labor Day, Sept. 7, is cold enough to see your breath. The farmhouses around Oshkosh are already framed with trees dappled orange and red.

The parking lot at the Ron Johnson for Senate headquarters on Oregon Street is filled, as the campaign’s statewide staff has grown to 51. Visitors are greeted by a dog named Bourbon, a Shar-Pei owned by Kirsten Hopkins, Johnson’s principal fundraiser.

Staffers occupy the rows of cubicles. They all walk with sheaves of paper clutched in their hands, as if the fate of the campaign hangs on those sheets. Johnson’s son Ben and daughter Jenna, also working on the campaign, wander the halls. They are easily recognizable, given their ubiquitous position on televisions all over the state. Given, they’re not exactly “stars” per se, but this is Oshkosh — they might as well be Tom Cruise and Miley Cyrus.

Johnson, 55, a thin man who wears a constant look of purpose, is sitting at a large wooden desk in his office, getting ready to do a national interview with Sirius XM Satellite Radio. His spokeswoman, Sara Sendek, sits across from him with a pad in her hand. As he discusses pension issues with the host, he scribbles a drawing representing a sun, with lines shooting out of it.

The interview seems to be the standard Ron Johnson interview — he throws out statistics, while seeming a little short of breath. His hands shake a little. But then, Johnson is asked a question about health care, and the whole interview dynamic shifts.

He begins discussing daughter Carey, who was born with a heart deformation 27 years ago. At the time, her specific disease was considered to be 75% fatal. Ron went from doctor to doctor, searching for one who could perform the procedure to save his little girl’s life.

And it is golden. Suddenly, by talking about something from his own experience, Johnson has come to life. Like flipping a switch, he has gone from being a candidate to being a dad.

After the interview, we talk about his verbal flubs. Early on, his campaign had been hobbled by some of his public comments. During the British Petroleum oil spill debacle, Johnson had said “I’m not anti-Big Oil.” He called free trade “creative destruction,” implying that people had to lose their jobs to factories overseas in order to create new jobs here in America. He had said that “poor people don’t create jobs.” He expressed his opinion that people should be able to get their primary health care at Wal-Mart. And in an interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel editorial board, he said he believed sunspots were one of the causes of global warming.

I ask him about sunspots. He shrugs. “Sometimes you just say things,” he says. I ask him if he thinks reporters are purposely trying to trip him up now. “Absolutely,” he answers.

The conflict in Johnson is evident — he got into the race because of his disgust with smooth-talking politicians. But now, he’s struggling to become a plausible politician himself. People say they want an outsider, but once a candidate gets too outside, it harms their brand. (Ask Republican Delaware Senate candidate Christine O’Donnell, who had to buy an ad denying she is a witch.)

Johnson’s staff has been working with him on committing errors of omission rather than errors of commission. Nobody will ever criticize you for something you don’t say, they tell him. He is now aware that things he does say can cost him a million dollars’ worth of ads.

While the Sept. 14 Republican primary was a mere formality (Johnson scored 85% of the vote), the news following the primary proved to be a surprise. A Rasmussen poll conducted the day after the primary showed Ron Johnson up 51%-44% on incumbent Russ Feingold. The campaign had expected a post-primary bump, but not that kind of bump.

Seeing his numbers begin to slip, Feingold began to step up his attacks on Johnson. The first came in the form of a television ad Feingold ran featuring news footage from a Madison television station that investigated whether Johnson had gotten government assistance to start his business 31 years ago.

It includes a clip of Johnson saying he never lobbied for “special treatment or a government payment,” then shows headlines indicating Johnson received $4 million in “government” loans to aid his business.

At issue was a tool called industrial revenue bonds, which pay tax-free interest and consequently allow a business to pay a lower interest rate on financing secured from the private underwriting market. There is no government guarantee, no government money, and the taxpayers are never at risk — and Johnson’s company paid it all back on time.

To counter this attack, Johnson’s campaign contacted two former Wisconsin secretaries of commerce, Bill McCoshen (who served under Gov. Tommy Thompson) and Dick Leinenkugel (whose service under Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle killed his own chances of running for the GOP Senate nomination Johnson eventually won.) The two secretaries wrote a letter pointing out that IRBs aren’t “government aid,” as Feingold’s ad suggested.

This was one of the Feingold attacks that the Johnson campaign had anticipated. While it’s much publicized when a candidate hires a private investigator to dig up dirt on an opponent, more often a candidate will hire someone to investigate him or herself.

This steels the candidate for the negative information the opponent is likely to use. Johnson’s campaign did just this, so it already had a good list of the attacks Feingold was likely to launch.

In fact, the tricky part of running a campaign isn’t knowing what will be used against you, it is guessing when those things will be deployed by your opponent.

In July, deputy campaign manager Jack Jablonski assumed Feingold’s next negative attack would be on free-trade issues. The attack came, but not until mid-September, when Feingold began running ads accusing Johnson of supporting international trade agreements like NAFTA, which Feingold said cost Wisconsin 64,000 jobs.

In late September, the Johnson campaign heard that he would be attacked for his involvement in the Catholic school system in Green Bay and the Fox River Valley. For years, Johnson had donated millions of dollars to Catholic schools in northeastern Wisconsin, despite not even being Catholic himself.

When a bill came before the Legislature to lift the statute of limitations for people wanting to sue the church for sex crimes, Johnson opposed it. He thought that it would make Catholic schools a magnet for lawsuits that could bankrupt them. While Johnson supported tough criminal penalties for pedophiles, he didn’t want to see all the good work he was trying to do torn apart by lawsuits based on events from 30 years earlier. He also worried that such “window” legislation could harm other non-profits like the Boys & Girls Clubs.

On Sept. 28, a publication called Veterans Today published the video of Johnson’s testimony against the bill before the Wisconsin Legislature.

In the video, a bearded Ron Johnson, looking like a skinny Wolf Blitzer, reads through his objections to the bill — a bill, incidentally, on which the Democrat-controlled Legislature agreed with Johnson. It didn’t clear either house.

Nevertheless, the Johnson campaign took proactive measures to get ahead of the story. The left-wing blogosphere pounced immediately, posting “Ron Johnson supports pedophiles” entries everywhere. MSNBC host Keith Olbermann had a victim of pedophilia on the air to discuss his disgust with Johnson.

But Johnson’s campaign was ready. It issued a fact sheet on the allegations that communications director Kristin Ruesch had drafted back in April while working at the state Republican Party. Johnson called for full disclosure by the Green Bay diocese in any ongoing investigations. Calls were made to media outlets all over the state to explain why this was a non-story.

And it worked. A story by Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigative reporter Dan Bice rumored to be following the allegations never materialized. (Bice had done an article on the issue two months earlier.) The story faded.

But the campaign wasn’t out of the woods just yet — there was still material out there that could be used against Johnson. Running a campaign is very much like the movie Carlito’s Way — just when you think you’ve escaped, Benny Blanco from the Bronx returns to take you out.

And the left-wing blogs kept trying. Their next charge was that Johnson had once hired a sex offender in his plastics plant. Never mind that in Wisconsin, it is against the law to consider someone’s arrest or conviction record in a hiring decision. But because Johnson did hire this man, feeling he had been rehabilitated, that was used against him. (In any other circumstance, these same liberals would be all for giving ex-cons a second chance at employment.)

None of the attacks stuck. A Rasmussen poll taken on Sept. 29 had Johnson up by an eye-opening 54%-42% margin. The day before, he had issued two new ads — one featuring the candidate standing in front of a whiteboard writing down the number of lawyers that currently serve in the Senate (57), as opposed to the number of accountants (1) and manufacturers (0). In the initial ad shoot, the numbers were wrong, so the ad had to be re-shot and some CGI blurring added to correct the numbers.

The second ad was slightly more negative in tone. (Campaign rule: If your opponent is running a negative ad, it’s called a “negative ad.” If your campaign is running a negative ad, it’s called a “contrast ad.”) The ad criticized Feingold’s vote for the health care bill, noting that before the bill passed, 55% of Wisconsinites opposed a “government takeover of health care.”

(The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel labeled the entire ad as “false,” as it incredibly didn’t believe the bill amounted to “government health care.”)

It wasn’t a hard-core negative ad, though, and the health care bill is fair game under any circumstance. Jablonski said that, given Johnson’s big lead, the plan was to stay positive.

In that vein, the campaign also cut an ad with Johnson and his daughter Carey, discussing her heart problem. But it needed to be re-shot, because the campaign felt Ron didn’t deliver his lines with enough emotion.

The goal was to get a positive ad on the air featuring Carey, who, it was felt, “presents well on TV” (campaign-speak for “she’s hot”). Eventually, the ad was shelved altogether, as staff believed it didn’t pack the emotional punch they had anticipated.

Simple yet effective, Johnson’s ads were the envy of campaigns around the country.

Brad Todd, who produced the ad for OnMessage Media, said his competition isn’t the other candidate, but the ads that air directly before and after his campaign ad. “What you produce has to hold a viewer’s attention and look like it belongs with all the other ads on the air,” he said.

Soon, Johnson’s measured, disciplined campaign started to get national recognition. At the Washington Post’s “The Fix” blog, Chris Cillizza said Johnson “has run one of the best — if not the best — Senate campaigns this cycle.”

The Oshkosh Northwestern, Johnson’s hometown paper, called his campaign staff “brilliant.” The Washington Times said, “aided by a smart and savvy campaign staff, [Johnson] has refined his message and appearance.”

Feingold wasn’t helping his own case by stumbling into a few uncharacteristic missteps. For instance, one of the senator’s favorite talking points was that he has been outspent in every one of his Senate races. For this oft-repeated claim, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s “Politifact” feature deemed Feingold a “Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire,” as he significantly outspent challenger Tim Michels in 2004.

In an interview with the Journal Sentinel editorial board, Feingold complained about Johnson’s insistence that the 18-year senator was a “career politician.” “I think it’s a pretty sad thing for our society when somebody runs a campaign telling young people, ‘Don’t you dare go into public service, or you’re going to be mocked,’” Feingold told the board.

Of course, it was Feingold who, within weeks of joining the race, called Ron Johnson a racist, implied he was a communist sympathizer, and had fabricated his positions on a number of issues. So exactly who was keeping people from entering politics? Did Feingold expect a telethon for three-term U.S. senators?

Feingold even bumbled his television ads. On Oct. 1, he began running an ad bragging about his vote for the poisonous health care bill — a bill that, according to Rasmussen, 57% of Americans wanted repealed (46% “strongly”). At the end of the ad, two women urge Ron Johnson to “keep your hands off my health care.” As if people couldn’t figure out that a government takeover of health care is the ultimate “hands on” approach to medical care.

From watching the ad, one would get the impression that it was Ron Johnson who wanted to take over health care — the truth, obviously, was the exact opposite.

But that paled in comparison to Feingold’s next TV blunder. On Oct. 5, the Feingold campaign ran an ad accusing the Johnson campaign of “dancing in the end zone” too early. The video featured a clip of one of the most notorious moments in recent Wisconsin sports history — then-Minnesota Viking Randy Moss mooning the crowd in a playoff victory over the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field. (In an odd twist, Moss was traded back to the Vikings from the New England Patriots the very day the ad began running.)

As soon as the ad appeared, the Johnson campaign sprang into action, calling the National Football League offices. Since anyone who has ever watched an NFL game knows that footage of the games is copyrighted material, the Johnson campaign suspected Feingold hadn’t gotten clearance to use the clip in his ad. Indeed that was the case.

That very afternoon, Feingold had to pull the ad per an NFL directive. How ironic! Here was Russ Feingold — who had made a career of telling people what was permissible to put in television ads — having to cancel his own ad for using illegal material.

Feingold’s missteps helped Johnson stay ahead in early October: a “We the People” poll showed him up 49%-41%. But that didn’t necessarily mean all was well with the campaign staff.

The pressure was causing significant fissures within the staff. This is common with campaigns. By the end of the race, people who have been trapped in a headquarters for months can barely stand the sight of one another. Among the Johnson campaign staff, these divisions ran deep.

People began moving desks around to avoid one another. Some staffers appeared to be more concerned about landing a job with Sen. Johnson than doing the work they had been assigned. There was talk of firing troublesome staffers, but with a month to go, there was no time to train replacements.

The campaign was also fending off political consultants. Three months earlier, when Johnson was a long shot, the campaign had struggled to find help. Now, with the polls showing the candidate well ahead, consultants descended like locusts.

Undoubtedly, they had resume-padding in mind, wanting to share credit for the expected stunning Johnson win. If victory has a thousand fathers, the Johnson campaign was quickly becoming the Maury Povich Show of campaigns.

The campaign was also rebuffing national politicians who wanted to come to Wisconsin to campaign for Johnson. But since Johnson was running as the anti-politician, he turned almost all of them down.“You name the national Republican figure, and we told them there were better places they could be,” said one staffer.

One state senator called to tell the campaign it could improve Ron’s numbers by buying an ad in a political leaflet printed in a Milwaukee-area conservative activist’s basement. Other state legislators, despite never having run a competitive race, called on a daily basis to offer advice.

But even with all of these sudden pressures from the outside world, the campaign had to deal internally with its most daunting task of all: Johnson had to get ready to debate one of the U.S. Senate’s most capable orators, Russ Feingold.

The constant drumbeat of negative stories during September created a schism within the campaign staff. Ruesch and Sara Sendek, the public relations team, wanted to keep open lines of communication with the press. They felt that’s what they were there for — to deal with reporters and hopefully head off more negative stories.

Campaign manager Juston Johnson and Jablonski, on the other hand, had a different philosophy. Johnson (who’s unrelated to the candidate) indelicately described his preferred strategy as “don’t ever f@#*king talk to the media. For any reason. Ever.”

They figured the press was going to write unflattering stories about Johnson no matter what, so there was no sense in giving them more material. And their best bet was taking Ron’s message directly to the voters, via television ads.

“The press is worse than the Feingold camp,” said Jablonski. “We spend a lot of time worrying about the press, and almost no time worrying about Feingold.”

This discussion continued up until Oct. 22, when Johnson arrived in Milwaukee for the third and final debate with Feingold. Johnson and Feingold appeared on stage at Marquette’s new law school, took some photos together, and settled into their seats.

It was an uncomfortable 20 minutes before the debate would actually begin — during which time Feingold smiled and joked, and Johnson sat and stared straight ahead.

Once the debate began, it was clear that it was going to be monumentally boring. This was the best-case scenario for Johnson. Feingold had the chance to stir things up, but chose to keep the debate restrained.

Johnson did an adequate, if unspectacular, job of answering questions. In the weeks leading up to his first two debates, he had been through endless hours of often confrontational debate prep with his staff. For this debate, he was told not to refer to the “Bush tax cuts.” He uttered the term once, but then when it came back around, he said the letter “B” before stopping himself and saying “the 2003 tax cuts.”

(When asked later about how he felt about his staff telling him what specific words to use, he pursed his lips and said, “It’s annoying.”)

As the debate moved on, it became clear that this wasn’t a contest between Ron Johnson and Russ Feingold. It was a debate between Feingold and the voters of Wisconsin. Feingold tried to convince the audience that the health care and stimulus bills he supported were to their benefit. Polls showed that the public strongly disagreed. Johnson’s presence was almost superfluous.

At the end of the debate, one stunning fact was clear: Feingold knew he was going to lose the election. But he was going to lose like a man.

After the 90-minute debate, Ruesch and Sendek retreated to their holding room, where Sendek furiously banged out a press release. Johnson, his brain freed of debate facts and linguistic rules, strode out into the night to speak to 400 GOP loyalists at Serb Hall on Milwaukee’s southside. But first he had a message for one of his staffers:

“That was hard.”

In early April of 2010, Michelle Litjens, chairwoman of the Winnebago Republican Party, found some local guy who was thinking of running for the U.S. Senate. She brought him to a meeting of conservative operatives in Madison. He didn’t even know he was supposed to speak, and patched together a few talking points in the car on the drive down.

When Litjens introduced businessman Ron Johnson, people rolled their eyes and checked their watches as he ambled through his reasons for running. There were already a few people thinking about running for Senate, even Wisconsin political legend Tommy Thompson.

The last thing Wisconsin needed was another rich guy to serve as fodder for the Feingold political machine. Just who did this thin-faced, white-haired guy think he was?

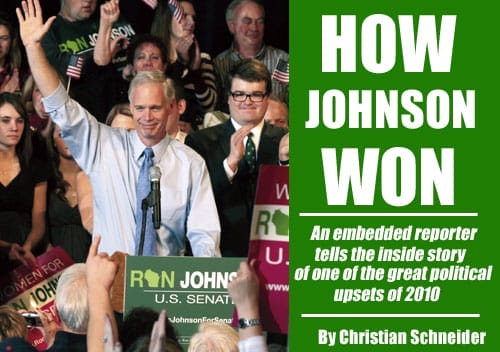

Six months later, everyone found out. He was Ron Johnson, Republican senator from Wisconsin. Just months ago, Johnson had decided to run because he abhorred politicians — now he had become a plausible one himself.

On election night, Democrats suffered a bloodbath. Republicans won more than 60 seats and regained control of the House of Representatives. In the Senate, the GOP picked up six seats, short of the number needed to take control.

Yet many of the states where the GOP gained seats (Illinois, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, North Dakota, and Indiana) routinely elect Republicans statewide; Wisconsin hadn’t elected a GOP U.S. senator since 1986.

National media darlings like Marco Rubio and Rand Paul sailed to election, but did so in seats previously held by Republicans. Ron Johnson’s pickup stands alone as perhaps the most stunning GOP victory in 2010.