Discord has split the state Supreme Court, damaging its productivity and reputation for fairness

Using bitingly personal language, the seven justices of the Wisconsin Supreme Court spent much of the current term arguing over, among other things, when and whether they could be forced out of cases before the court.

Given how few cases have actually been resolved as the term winds toward its August end, skeptics might ask a different question: When might they actually consider a few?

As both ideological and deeply personal disputes become increasingly public, the court’s members are issuing fewer opinions than any other Wisconsin Supreme Court in decades, according to their own statistics. The opinions they are working on, moreover, appear destined for release in a spastic flurry at the very end of the term.

Meanwhile, a long-term trend continues unabated: Fewer and fewer citizens feel it’s worthwhile to even petition the high court for justice.

Well-chronicled verbal jousts among the justices — including comments that opposing arguments are “ridiculous,” “incoherent” or politically motivated — are not entirely new. They echo the very public battles Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson waged with other justices 10 years ago. This time, though, there is reason for more serious concern.

Former Justice William Bablitch, who retired in 2003 but still practices law, does not track the statistics but is well aware of the court’s inner workings. And he is blunt.

Acrimony “can’t help but be impeding the way the court is supposed to function,” he says. “The personality rifts are extensive and deep, and it seems sometimes the decisions are more an expression of will than law.”

The “acrimony certainly has to affect the way you listen to your colleagues,” he adds. “The conservative bloc, after being called name after name, cannot help but not listen as well to the liberal bloc, and vice versa.”

Not everyone agrees the court’s performance has suffered from the strife. Greg Pokrass spent almost 25 years as a Supreme Court commissioner before leaving in 2005. The level of acrimony was “pretty bad” then, he says, and appears even worse now. But “if someone were to say, ‘This is all bullshit and they are turning out crap,’ I would say, ‘No. I don’t think so.’”

Others see it differently. Prominent attorneys on both ends of the political spectrum use words like “sloppy” and even “horrendous” to describe recent opinions, and some justices themselves have openly speculated that political considerations are influencing what should be strictly legal issues.

Many attorneys declined to talk on the record, but veteran Madison attorney Lester Pines appears to speak for a broad segment of the Wisconsin Bar when he says, “We would like to think that judges on a collegial court can bridge whatever differences they have and focus on the legal issues before them.”

He adds: “We…want to believe that the arguments we are making are being considered on their merits and are not subject to personal disputes among justices on the court.”

There is worry, Pines admits, “that one justice might instinctively react to another and shut off debate of a legal analysis because of personal animosity.”

There was a time when observers attributed court conflicts to old-school misogyny. For her first 17 years on the court, Abrahamson was the only female justice. Today, there are more female justices — Abrahamson, Patience Drake Roggensack, Ann Walsh Bradley and Annette Kingsland Ziegler — than male. Gender, though, is about the only thing some of them have in common.

There are deep ideological differences, to be sure. Abrahamson and Bradley are the two liberal stalwarts, and the court’s longest-serving justices. According to data compiled by the Wisconsin Law Journal, they are also virtual clones. They agreed with each other in 98% of all cases in the 2008-09 term.

Roggensack anchors the other end of the spectrum. The conservative jurist, first elected to the court in 2003, concurred with Abrahamson in only 60% of decisions in the last term, according to the Law Journal, and in less than half of the torts and insurance cases. The court’s two newest and youngest justices, Annette Ziegler and Michael Gableman, sided with Roggensack 94% of the time, the Law Journal found, while David Prosser concurred with her 86% of the time.

Though perceived as increasingly liberal, Justice Patrick Crooks concurred with Roggensack almost as frequently as Prosser did — although not always on the same issues and certainly not on one that has consumed much of the court’s time and energy: recusal, which is when a judge must remove himself or herself from hearing a case because of perceived bias or a conflict of interest.

There are, in fact, numerous recusal issues that have proved to be uniquely divisive — partly because they raise very personal questions about judicial impartiality but also because they feed into broad ideological conflicts that starkly play out in judicial elections.

Recusal first became a high-profile issue when Ziegler ran for the court three years ago. She was pilloried — and eventually made the subject of a long, drawn-out ethics inquiry — for not, as a Washington County Circuit Court judge, recusing herself from pro forma rulings in cases that involved a bank for which her husband served on the board.

Apparently deeply stung, she later removed herself from a Supreme Court case involving the Wisconsin Realtors Association because the group had given her campaign $8,625. However, she declined to step aside in a different case involving Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, which independently spent $2 million supporting her election.

The two groups (as well as the League of Women Voters) eventually filed petitions with the court asking for clarification on when recusal is appropriate — something that, in turn, prompted lobbying by other organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University and a group known as Justice at Stake.

Both groups describe themselves as nonpartisan proponents of improving democracy and justice. But at a public hearing last fall, Prosser made it clear he thinks they have goals far beyond stricter recusal rules. He pointedly suggested that they are subtly pushing for appointed, rather than elected, justices — a goal most often sought by the left side of America’s legal community.

After quizzing the director of state affairs* for Justice at Stake about the group’s alliances with liberal organizations, Prosser asked whether it has any conservative partners and alluded to the fact that hedge-fund billionaire George Soros, a key supporter of liberal causes, provides funding to Justice at Stake through his Open Society Institute.

In response to a question from Wisconsin Interest, OSI issued a statement saying the organization does “not take a position as to which method of judicial selection — election or appointment — is best” but added that it is concerned about the influence of special interests and does include “merit selection” of judges and public financing as possible solutions.

Representatives of both the Brennan Center and Justice at Stake deny advocating for appointed jurists — although a look at Justice at Stake’s website as recently as late May gives credence to Prosser’s question.

The site featured a New York Times commentary written by former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who believes judges should be appointed based on merit, and only after they are on the bench for a time, take part in elections. It was entitled, “Take Justice off the Ballot.”

O’Connor has a long Republican pedigree, which demonstrates that the debate over elected-versus-appointed judges does not clearly break down along political lines. But liberal lawyers, aware that conservative judges often fare better with voters, are generally more apt to prefer appointments.

The issue has particular resonance in Wisconsin, where the three longest-serving justices are the most liberal, and have seen conservatives take over the court through elections in recent years. There is much more at issue than how justices get on the court, however. There are questions, also raised during recusal debates, about what they are doing once they get there.

A majority of justices — Prosser, Ziegler, Gableman and Roggensack — eventually sided with WMC and the Realtors on recusal, adopting a rule that endorsements, campaign contributions and independent ads cannot alone constitute grounds for removing a justice from a case.

The debate, though, brought to the forefront yet another contentious dispute — charges and countercharges that cases or motions are not being dealt with as quickly as they should be, and impeding the pursuit of justice.

During a recusal discussion last December, Abrahamson charged that some of her brethren were delaying the release of their written work merely because they didn’t like a dissenting opinion.

Roggensack was plainly incredulous. “What are you talking about?” she asked Abrahamson. “I have no idea what case you are talking about.”

The chief justice herself, Roggensack argued that day in December, had not only held a case for “month after month after month after month” but was making confidential inner workings of the court public in order to “pose for holy pictures.”

Roggensack added that as a result of Abrahamson holding a case known as State v. Allen, the court had received “repeated motions from other defendants in criminal cases.”

Allen, she said, “should have been decided back in April, before we left for the term last summer.”

“Well, speaking about revealing confidences…,” said Abrahamson.

“Well, you started it, kiddo,” retorted Roggensack. “I mean, you opened the door.”

Both Roggensack and Abrahamson were referring to cases involving recusal motions, but Bradley suggested that “other things” were also being held up. She declined an interview request, so it’s not clear what she was suggesting.

What is clear, though, is that the court’s deliberations have seriously slowed.

The median release date for opinions in the mid-1990s was April or May, according to statistics compiled by a lawyer deeply interested in the court’s workings.

Nowadays, it’s June — and the delays seem to be getting worse. The court, in the current term, had released a grand total of only eight opinions on civil and criminal cases by May 1, down from 19 at that point in the previous term.

In the last term, moreover, the court issued only 64 opinions in civil and criminal cases and only 87 total (including attorney discipline cases handled largely by court commissioners), according to court statistics.

As recently as 2004, by comparison, the court resolved a total of 141 cases (including discipline issues) through opinions. The year 2004 was particularly busy, but the court has never issued fewer than 100 opinions in any 12-month period, according to statistics going back to 1990.

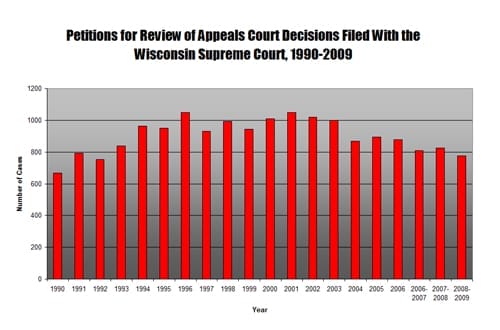

The court is simply taking fewer important cases. In calendar years 2001 and 2002, the court accepted around 70 petitions for review of Appeals Court decisions, for instance. In calendar years 2003 and 2004, they accepted more than 100. During the 2008-2009 term, the court granted only 47, according to its annual statistical report. There are many possible statistical measures, but all suggest similar decreases in productivity.

The number of petitions for review of Appeals Court cases filed, in the meantime, has also dropped steadily from more than 1,000 per year in calendar years 2000, 2001 and 2002 to 777 during the 2008-2009 term.

No one claims the justices are lazy. If anything, the justices are fully engaged in the cases they do take — maybe too fully, some suggest. They just don’t seem to be able to let anyone else have the last word.

“I think that many [Supreme Court opinions] have gotten longer — in my opinion way too long — and there is no question that the dissents and the concurring opinions have grown since I have been there,” says former Justice Janine Geske.

Verbosity creates practical problems. Long opinions with lots of dissents or concurrences (and myriad conferences) are time-eaters. Instead of clarifying the law, a long opinion can sprout all sorts of tendrils that muddle the import of the decision — and raise issues in unintended ways.

Lumping all the justices together in this regard would be unfair.

In the Wisconsin Law Journal article, Catherine Rottier, president of the Civil Trial Counsel of Wisconsin, said she was “pleasantly surprised” by the opinions of the newest member, Michael Gableman.

“He was unknown to most of us before joining the court. Whether you agree with the results or not, the opinions were well-crafted and easy to follow,” she added.

Other members of the court, conversely, needed 142 pages of dueling opinions in State v. Allen to essentially state that Gableman — whom Allen contended revealed bias against criminal defendants during his campaign against Louis Butler — could remain on the case. That’s 131 pages more than the Warren Court used to issue its landmark desegregation ruling Brown v. Board of Education.

The Allen opinions were notable mostly for name-calling. But Prosser used the occasion to further lament what the conservative justices seem to see as a liberal offensive to thwart the court’s conservative majority from exercising its judgments.

“The Wisconsin State Public Defender’s office has invited the entire defense bar to file recusal motions against one of the justices in criminal cases,” he wrote in reference to Gableman. “The number and savagery of the motions is unprecedented and amounts to a frontal assault on the court.”

Gableman is, of course, also the subject of a complaint filed by the Judicial Commission over a highly publicized commercial he ran that inaccurately suggested that Butler, when he was a practicing attorney, was responsible for the release of a defendant who went on to molest a child — a complaint that Gableman’s fellow justices must rule on.

The court is not merely divided on recusal issues or, perhaps, the fate of Michael Gableman, however.

“This is a deeply divided court, at a very philosophical level concerning how a state supreme court should function,” wrote Roggensack in that same Allen case.

The remark, it appears, was a less-than-subtle dig at Abrahamson. How a court operates is primarily a reflection of the chief justice, who controls a lot of the little stuff like scheduling and the length of conferences, and administrative minutia like who gets invited where.

It is the chief — who did not respond to interview requests for this story — who also sets much of the tone both administratively and in deliberations, those who have worked inside the court say.

Conservatives who have worked with Abrahamson concede she is smart, even brilliant. But their criticisms go beyond the age-old conservative lament that liberal jurists are too willing to discard legal precedent in search of end results they personally favor.

Bablitch, himself far from conservative, points to a long history of conflicts. Way back in the mid-1980s, the Milwaukee Journal quoted an unnamed justice as saying Abrahamson gave colleagues the finger in conference and ridiculed their opinions in her dissents. Long before Abrahamson was trading barbs with Prosser and Roggensack, she was locked in a public battle with Justice Roland B. Day. In 1999, four justices, including Bablitch, tried to convince voters to oust her — and failed. Abrahamson, who’s won four statewide races including an easy reelection in 2009, has been a durable voter favorite through it all.

Still, there has been consistent criticism of her management style. One lawyer who has worked in the court calls her style “toxic” and compared dealing with her to chewing tinfoil. In short, Abrahamson may be brilliant, but her critics say she doesn’t countenance other perspectives or much care about consensus or conciliation. She doesn’t look to the past, or precedent, so much as the future and opportunity, it is suggested.

The same lawyer remembers Abrahamson, more than once, gently ribbing a more conservative justice about something she didn’t agree with, saying something akin to, “Once you leave, don’t count on that one being around.”

She would say it like a joke, he said. Only it never much seemed like one.

Others on the court are not immune from criticism, and conservatives who are critical of Abrahamson can, of course, have agendas of their own. But such criticism has never been strictly ideological. Bablitch, after all, one of the four who publicly opposed her 11 years ago, was in some ways a legal soul mate.

A “good deal” of the responsibility for the acrimony, says the man who was a Democratic Senate Majority leader before he joined the court, “goes to her.”

Not everyone, to be sure, is critical of the court or its individual members. Chief Appeals Court Judge Richard Brown says, for example, that the cases the Supreme Court is reviewing are important ones.

“From my observation, it appears that, while there are a few exceptions, the Supreme Court is taking only those cases that have the potential for marking the trend of the law in Wisconsin — a law-declaring function. I don’t consider that to be a bad thing. I think it’s a good thing,” he says.

Some lawyers and judges, moreover, are not convinced that the court’s diminished caseload is necessarily a bad thing. Others, though, wonder openly what important legal issues are being ignored.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Roberts famously asserted that a judge’s job is to call balls and strikes. The truth is that judges also decide which pitches can even be thrown. On April 30, 2010, for instance, the Wisconsin Supreme Court announced it had accepted one new case. That very same day, the justices also denied review of 57 others — including one known as S.C. Johnson v. Morris, a case in which the Racine-based consumer-products maker successfully sued the defendants for taking part in a civil conspiracy to overcharge for transportation services.

Franklyn Gimbel, a former state bar president who represented one of the defendants on appeal, says he was “devastated” by the Supreme Court’s decision not to consider important Fifth Amendment and evidentiary issues at stake.

“All I know is I have been practicing law for five-oh — 50 — years, and if there was ever a case with extraordinary issues that should have been reviewed by the Supreme Court it was this one,” he says.

“I am concerned,” he adds, “that the internal strife may have played a role in the denial of the review of this case.”

Asked to elaborate, he says that Abrahamson and Bradley “are people, I have at least heard on the street, who are segregated” on the court. The liberal justices both indicated they wanted to take the case, but did not have the third vote they needed.

That sort of public dissent on denial of petitions — once rare — has in recent years become common. Abrahamson, in this term alone, had by May 1 publicly indicated that she wanted to take 33 different cases that were denied. When the balance of power was different in the 2007-2008 term, it was the conservative Roggensack who publicly dissented 28 times on denials of petitions.

Among the justices there are fundamental differences of opinion, it is clear, even regarding which cases to accept.

The trends are not abating. By the end of April, the last month for which statistics were available, the court had accepted roughly the same number of cases as last year but appeared to be delaying the substantive ones — the civil and criminal matters — for release until the very end of the term.

Meanwhile, the number of petitions filed for review of Appeals Court decisions by May 1 was down 6% compared to the prior term.

There could be a variety of reasons for that drop, everything from the increasing cost of litigation, to fewer appellate court decisions due to a rise in mediation, to better-reasoned decisions at the Appeals Court level that litigants are willing to accept.

Bablitch, though, raises another reason. “It is also possible that the acrimony on the court is causing the lawyers to give a second thought to whether they want to go up there and roll the dice,” he says.

Whatever the reason for the seeming loss of faith in the court, if Wisconsinites fear that justice is subject to politics and to personal grudges, they will turn their backs on it. That is why the court, while it should never pander to public opinion, is right to worry about it.

“I am not bashing Abrahamson,” says Pokrass, “but I think the chief is the one in an institutional way who has to be a conciliator and leader and keep the acrimony to a minimum.”

Mike Nichols is the President of the Badger Institute.

Any use or reproduction of Badger Institute articles or photographs requires prior written permission. To request permission to post articles on a website or print copies for distribution, contact Badger Institute President Mike Nichols at mike@badgerinstitute.org or 262-389-8239.

* title corrected from the published version