Shortly after November’s presidential election, America’s pundit class was flush with theories about how President Obama could win every battleground state but one, despite presiding over four long years of an anemic economic recovery. Exit polls provided more evidence of what many conservative Latinos had feared for years: The GOP can’t find genuine and tangible ways to connect with Latino voters, and the party may fade into irrelevance as a result.

Take Rudy Garay, an El Salvadorian immigrant and self-described independent voter who lives in Milwaukee. This past summer, he played in a five-on-five soccer tournament where he and his family enjoyed free skirt steak and beverages, compliments of the Obama 2012 campaign. He didn’t think much about it at the time, but remarked that he couldn’t imagine Republicans running such an event. “They’re just not around,” he said with a shrug.

I asked Garay for his first impressions of the word “GOP.” He said, “I see a party grounded in religious [family] values, but they come off anti-immigrant and anti-student.” Asked to elaborate, Garay said that Republicans claim they’re about families, but promote enforcement policies that tear them apart. What can the party do to make things right?

“They should be thinking about creating more opportunities for immigrants,” Garay told me.

He hit on one of the keystones absent in the GOP Hispanic outreach plan — the party’s actual outreach. There is none. It’s reflected in GOP policies and embedded in GOP language. Even in areas where Republican policy is overwhelmingly popular in the Hispanic community — school choice, for instance — Republicans don’t even know how to promote it to minorities.

If you’re explaining to low-income Latinos that the greatness of school choice comes from its “free market” principles like “competition” and how they need to escape “big government education,” you might as well be Charlie Brown’s teacher. They won’t understand it, let alone give Republicans credit for pushing it. Hispanics don’t care about a free market education; they care about having parental rights in their children’s education. They want a say in curricula. They want a safe school environment.

This leads to the second keystone of how the GOP can rebrand itself to the Hispanic community. If you want to change the Hispanic perception of the GOP as just a bunch of white guys promoting the interests of wealthy businessmen, then you need to do something about what Hispanic children are taught in school. The foundational blocks of education need to be depoliticized so children can learn the non-empirical sciences such as history and literature in an unbiased environment.

Republicans have their work cut out for them, but there is a path to securing Hispanic votes.

As far back as the 1960s, Democrats have enjoyed high voter turnout ranging from 56 percent to 85 percent among Hispanics in presidential elections. These results have persistently puzzled a Republican Party that still firmly believes what Ronald Reagan said long ago: “Latinos are Republican; they just don’t know it yet.”

In 2004, President George W. Bush received 44 percent of the Hispanic vote, the highest level of support of any Republican presidential candidate on record. In 2008, that number dropped like a brick to 31 percent. In 2012, Republicans fell even farther, to 27 percent. The downward spiral had prompted the Wall Street Journal to ask, “How many other nonwhite groups can the GOP lose and still consider itself a national party?”

Although immigration isn’t the only issue that cost GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney Hispanic votes, it would be naive to think that the notion of “self deportation” wasn’t repellant to Hispanic support. For context, let’s review how Ronald Reagan’s 1980 convention platform addressed immigration. It reads:

“Republicans are proud that our people have opened their arms and hearts to strangers from abroad, and we favor an immigration and refugee policy which are consistent with this tradition. We believe that to the fullest extent possible those immigrants should be admitted who will make a positive contribution to America and who are willing to accept the fundamental American values and way of life.

“At the same time, United States immigration and refugee policy must reflect the interests of our national security and economic well-being. Immigration into this country must not be determined solely by foreign governments or even by the millions of people around the world who wish to come to America. The federal government has a duty to adopt immigration laws and follow enforcement procedures which will fairly and effectively implement the immigration policy desired by the American people.”

The talk of open arms and open hearts in Reagan’s convention platform is reminiscent of the glory days when Reagan conservatives recognized the historic contributions of immigration as a source of strength and stability for our great nation.

Contrast this with the words of Kris Kobach, an immigration advisor for Romney’s presidential campaign, who said, “We recognize that if you really want to create a job tomorrow, you can remove an illegal alien today.”

While immigration reform needs to be a starting point for the GOP, history has shown that granting amnesty is unlikely to win Republicans a majority of Hispanic voters any more than it helped Reagan’s successor. As columnist Peggy Noonan wrote in the Wall Street Journal:

“In fact, solving immigration is important politically to the GOP because it would remove an impediment to reconciliation. But immigration reform itself probably won’t result in any electoral windfall for Republicans. Mexican-Americans strike me as like the Irish who came to America in the great wave from 1880 to 1920. They saw the Republicans as snobs and establishment types, saw the Democrats as scrappy and for the little guy, and cleaved to the latter party for a good long while.”

Noonan is right. The GOP needs to look at the immigration quandary as a gateway issue, not an endgame. It alone will not stop the bleeding, but at least it opens the door to connect with an increasingly important voter bloc.

Working on immigration is great, but Latinos need to see Republicans in the community doing good things. Conservative nonprofits — particularly those with deep pockets — should invest in conservative Hispanic groups willing to do the legwork in the community: keeping neighborhoods safe and helping parents get their children into choice schools. Yes, school choice is an indispensable part of making gains among the next generation of Hispanic voters.

Shortly after November’s election, National Review Online writer Heather Mac Donald wrote a piece entitled, “Why Hispanics don’t vote for Republicans.” Although she provided no definitive conclusion, her message was clear: Latinos vote Democratic because they’re on the dole.

“Hispanics are for big government because they’re hooked on government help,” as she put it. Mac Donald didn’t think much of the emerging thinking on immigration reform either: “If only Republicans relented on their Neanderthal views regarding the immigration rule of law, the message will run, they would release the inner Republican waiting to emerge in the Hispanic population.”

She is both right and wrong. Transforming Hispanics into Republicans isn’t as simple as a tweak in government policy. But it’s misleading to say Hispanics are for big government because they’re hooked on government help.

Consider a study by the Pew Research Center showing that the preference for big government declines with each generation of Hispanics. The report states, “Support for a larger government is greatest among immigrant Latinos. More than eight in 10 (81 percent) say they would rather have a bigger government with more services than a smaller government with fewer services. The share that wants a bigger government falls to 72 percent among second-generation Hispanics and 58 percent among third-generation Hispanics.”

The aim of welfare liberalism — what conservatives commonly identify as liberalism — is to use government to emancipate people from the fear of hunger, unemployment, ill health and a failure to flourish in an industrial age, according to the Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. If this view of modern liberalism were truly adopted by the Hispanic community, we wouldn’t see a growing preference for smaller government with each subsequent generation.

I would suggest to all the Mac Donalds out there that it’s important to know whom you’re reaching out to if you want to change their voting behavior.

I looked at five decades of voting trends in presidential elections for clues. First, fluctuations in Hispanic voting patterns correspond to a candidate’s personal appeal. Second, Republicans have never reached more than 44 percent of the Hispanic vote in any given presidential election. Although there have been notable shifts in Hispanic voting patterns for Republicans, the general range rarely breached the 25 percent to 40 percent range. In the last election, Romney shot for 38 percent of the Hispanic vote but was lucky to get 27 percent.

Hispanics tend to support individuals who “get them.” My grandmother, a Texan of Mexican-American descent, was a longtime Democrat until George W. Bush came along. He was a fellow Texan who could speak Spanish and held traditional Christian values. For her, that connection was enough. For the first time ever, Lucia Rodriguez cast a ballot for a Republican. Not every Republican candidate can be from Texas or speak Spanish, but Hispanics need a point of connection.

As to my second and more important observation, the GOP can no longer be satisfied with a modest goal of 38 percent of the Hispanic vote. The question must be asked: What are the GOP’s long-term plans to grow the Hispanic vote?

To begin with, the GOP needs to know its opponents.

Consider Voces de la Frontera, a Latino worker rights group active in Wisconsin politics. Voces has filed two substantial lawsuits against the state — one against statewide redistricting and the other against requiring voter identification. Legal prowess aside, Voces’ ground game is nothing short of impressive: The group has one leg planted in Milwaukee and the other in Racine. These are two areas with dense Hispanic populations.

With the help of the teachers union, Voces has considerable influence in the Racine Unified School District and has an active youth arm called YES (Youth Empowered in a Struggle). In January, YES caught media attention in Racine for advancing a student “bill of rights” seeking, among other things, to establish a right to protect their schools from privatization (school choice), to “equal power dynamics in the classroom,” “a school environment where all teachers and staff have the right to collectively bargain,” and the right to resolve issues “by mediation” instead of using the police — a right they describe as the “restorative justice model.” Sounds like some pretty advanced stuff for a group of high school students, right?

Unfortunately, student activism hasn’t translated into student academic achievement in the Racine district. The high schools where YES are most active (Horlick, Case and Park) are classified by the state Department of Public Instruction as failing to meet expectations — the lowest of the five categories in assessing academic achievement. Horlick, Case and Park scored lower than 27 other Racine schools, but the consolation — if the School Board allows it — is that they get to use a restorative justice model to resolve school fights.

Just as revealing is YES’ support of collective bargaining for teachers. It suggests that the lobbying of the teachers union is shaping student opinion.

To attract Hispanic voters, conservatives need to couple community visibility with education reform. Traditionally, school choice has been sold on the merits of fostering competition and leading to academic gains. A study by economist Caroline Hoxby, then with Harvard University, now with Stanford, found that voucher schools helped improve the educational productivity of public schools.

In her 2003 book, The Economics of School Choice, Hoxby said, “Overall, an evaluation of Milwaukee suggests that public schools have a strong, positive productivity response to competition from vouchers. The schools that faced the most potential competition from vouchers had the best productivity response. In fact, the schools that were most treated to competition had dramatic productivity improvements.”

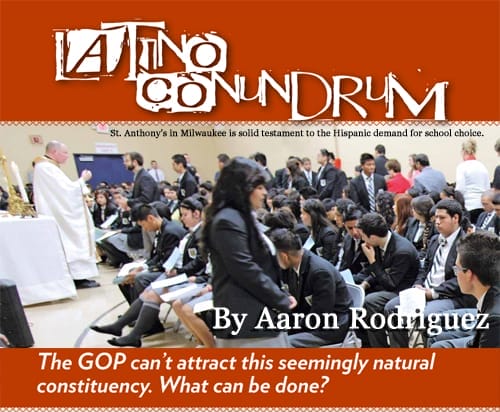

The improvements have not gone unnoticed. The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program has become an indispensable resource for the Hispanic community in Milwaukee. St. Anthony’s School in Milwaukee, a partner in the school choice program, grew from 400 to 1,400 students in just seven years. The school enrollment is almost entirely Latino, and it is now the largest choice school in the country. Of the 1,650 current students, 99 percent enroll via the school choice program. St. Anthony’s striking enrollment growth is not happenstance; it’s a solid testament to the market demand for school choice in the Hispanic community.

Polling conducted by the American Federation for Children, a national school-choice advocacy group, showed that 91 percent of Latinos in Arizona, Florida, New Mexico, New Jersey and Nevada support vouchers or scholarship programs for their children. Wisconsin Republicans should take note.

Choice schools are vitally important to the Latino community.

According to OpenSecrets.org, the National Education Association — the largest teachers union in the country — spent 91 percent of its 2008 political contributions on the Democratic Party, which strongly opposes school choice. In the same year, the American Federation of Teachers — the second largest teachers union in the country — spent 99 percent of its political contributions on Democratic candidates.

Here is my question: Can parents reasonably expect their children to learn about American history and American government without hearing the political biases of dues-paying members of these labor unions?

I think not.

Consider the collective bargaining battle in Madison last year. I spoke with a parent whose child was attending Victory School for the Gifted and Talented in Milwaukee. The parent said that on two occasions her child came home asking about Gov. Scott Walker.

A second-grade foreign language teacher at Victory reportedly asked her second grade class for a show of hands to see whose parents had planned to vote for Walker in the recall. On another occasion, the teacher reportedly told the class she would protest in Madison because the governor wanted to cut her pay. Surely, the reader is wondering why a foreign language teacher is conducting a political survey of second graders. One might also think that 7-year-olds are a bit young to understand the intricacies of collective bargaining.

I contacted Victory School for comment. The school would not put me in contact with the teacher, but sent me a copy of school policy that states: “Political advertising/advocacy shall not occur in school buildings or upon school premises during work hours in the presence of students.”

The notion that unions influence how teachers practice their craft appears to be a very well-kept secret. I’ve consulted “philosophy of education” essays produced by the world’s best academic minds. They endlessly scrutinize the philosophical problem of how a single public school system can address multiculturalism borne of a pluralistic society (for instance, Robert Fullinwider, Public Education in a Multicultural Society), but appear entirely unaware that the ideological leanings of labor unions could shape classroom instruction.

Consider Mexican-American studies taught in Tucson, Arizona. At the request of a student, Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal sat in on an ethnic diversity class in Arizona and witnessed a teacher talk about the oppression of people of color by “Caucasian power structures.”

According to Huppenthal, the teacher distilled America’s history as a conflict between civilizations where race became an overarching theme. What had not gone unnoticed was a poster of Che Guevera on the classroom wall, which, to Huppenthal, romanticized the well-documented violent history of Cuban Communism.

Former Gov. Tommy Thompson, meanwhile, has talked of his schoolteacher wife banned from the teachers lounge. Her crime? Being married to him. Such experiences don’t exactly scream coexist.

I interviewed Kenosha high school teacher Kristi Lacroix, who became an overnight sensation after appearing in a pro-Walker ad describing the Democratic-driven recall as “sour grapes.” For being on the “wrong” side of the union issue, she says she was regularly humiliated, harassed and intimidated by her union colleagues.

In a phone interview, she gave me at least 15 examples of repercussions characterized as disinvites by colleagues, a double standard in the application of school rules, intimidation and shunning. She said the tactics sent a clear message to colleagues that joining her in civil dissent would translate into similar treatment.

I asked Lacroix if she thought liberalism was actively taught in the classroom. Her retort, “They don’t need to. It’s embedded in the curricula.” She said it showed up even in math word problems where kids were asked to solve problems involving the redistribution of wealth.

Admittedly, it is easy to second-guess any curricula. Generally, the areas of controversy tend to lie less with the empirical areas of learning like math and science and more with the interpretive fields like history, the social sciences and the humanities. Whether liberalism seeps into government curricula is certainly subject to debate, but labor unions have a vested interest in this fight.

The GOP can try to curtail the influence of teachers unions across the country, but there’s no guarantee that such reforms will make government schools a more politically neutral environment for learning. In a society as pluralistic as ours, it makes sense that Americans should have the parental liberty to choose their own schools using their own taxpayer dollars.

The Hispanic community needs that choice. In the words of the great economist Milton Friedman, “We believe, and with good reason, that parents have more interest in their children than anyone else and can be relied on to protect them and to assure their development into responsible adults.”

Let Hispanic parents choose their children’s schools, and the GOP will see a change in how Latino voters view the Republican Party. Reversing the downward trend in the Hispanic vote may just be that simple.

Aaron Rodriguez contributes to El Conquistador, a Milwaukee Latino newspaper, and blogs atThe Red Fox.