Paperless Future

Overtaken by the Web and battered by the recession, Wisconsin’s 32 dailies are in a world of hurt.

By Marc Eisen

If you’re a deep-pocketed business executive in a flourishing industry, you gather at the richly appointed Fluno Center on the UW-Madison campus for your deep-thought conferences. More modest enterprises and nonprofits send their execs to the UW’s shop-worn Pyle Center for their soul-searching. This, of course, was the proper setting for a worried group of newspaper executives on March 28, 2008.

The good news was that they weren’t squirreled away in a dining room at Denny’s out on the Interstate. Given the parlous state of newspaper economics, this might have made more sense. Their papers might have split the cost of the $5.99 “Grand Slam” breakfast special.

“We’re in a time of decline,” Stephen Gray of the American Press Institute told the 60 or 70 people present. “It’s a time of fear, depression, even despair.” Yes, fear, depression, even despair. Nobody was shocked by Gray’s words, because everybody knew they were true.

The newspaper world, Wisconsin’s included, was one big car crash, with bodies strewn all over the road. Revenue was hemorrhaging like blood from a ripped artery. Readers were fleeing the scene of the accident.

Gray’s pitch, based on the research of the American Press Institute’s “Newspaper Next” project, was to not abandon hope. That news operations could remake their business in the next three to five years if they stopped thinking of themselves as “newspapers” but as online news and information purveyors who assiduously kept in touch with the needs of their advertisers and readers.

As benign as Gray’s message seems, these were radical words for newspaper people. Dailies had long functioned as imperious quasi-monopolies for local print advertising, exacting kingly tribute from the captive advertising of Realtors, car dealers and classified clients. Many newspapers – including my own, the alternative Madison weekly Isthmus – prided themselves as gatekeepers deciding what important matters should be brought to the public’s attention. Now, guys like me were getting their comeuppance.

Gray finished his presentation around 4 in the afternoon, leaving 30 minutes for questions and discussion, and here’s where things got strange. Nobody said anything. Not a word. Not a question. Dead silence from ad directors, publishers and the odd editor. It was so quiet you could hear a lid closing on a coffin.

So, what does the future hold for newspapers? “Oh, nobody knows anything,” Jim Baughman, chair of the UW-Madison journalism school, breezily told me nine months later. “Having studied the history of change in communications technology, I know that a lot of people put their chips on the wrong number.”

There was nothing breezy about Bill Johnston’s tone when he echoed Baughman’s assessment. “No one can tell what the future will bring,” the publisher of the Wisconsin State Journal said. “Who knows what the president’s stimulus package is going to do? Or if money will start flowing again? There are so many unknowns out there…. I have no clue.”

No, check that. Johnston does have a clue, and he’s honest enough to say what everybody else in the newspaper industry knows in their bones is true: “Revenue will certainly not return to where it was five or ten years ago…. There’s no doubt about it: We aren’t going to see those days again.”

Of course, the real question is, how many daily newspapers will be left in five or ten years? Or two years, for that matter?

Newspapers face “catastrophic problems,” as Mark Potts wrote on his “Recovering Journalist” blog. Their death “will come sooner than later,” Adam Reilly predicted in The Boston Phoenix. David Carr, the always entertaining media columnist for The New York Times, may have summed up the situation best: “Clearly, the sky is falling. The question is how many people will be left to cover it.”

Just as Gutenberg’s movable press broke the monopoly of monkish scriveners, the web has undermined the authority of old-form media titans like newspapers. To cite just one example, the free listings of Craigslist have all but destroyed the lucrative lock that newspapers had on paid classified advertising. Readers and businesses can now create their own customized online media worlds. The carnage has been extraordinary for newspapers.

2008 was the worst year in newspaper history. Publicly traded newspaper stocks suffered an average decline of 83%. Eight publishing companies dropped more than 90%. (And you thought the S&P 500’s decline of 39% was stomach turning.) The best performing newspaper stock, The Washington Post’s, lost 52% of its value.

Overall, an astonishing $64.5 billion in newspaper value vaporized in 2008, as analyst Alan Mutter reported in his indispensable media blog, “Reflections of a Newsosaur.”

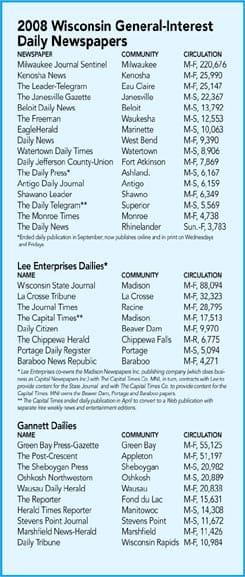

The bloodletting has ominous implications for Wisconsin’s daily newspaper industry, which began 2008 with 34 general-interest daily papers and ended 2008 with 32, as the Capital Times in Madison and The Superior Daily Telegram retreated to the web and twice-weekly publication.

The two biggest owners of state dailies – Gannett, which has 10 papers in Wisconsin; and Lee Enterprises, which owns or co-owns seven dailies – are among the most bloodied newspaper entities.

Gannett, the nation’s largest publisher with 85 dailies, including USA Today, laid off about 3,000 employees in 2008. Historically, Gannett papers have been cash cows, running profit margins from 20% to a whopping 40%. But the crunch has staggered even this legendary moneymaker. Ad revenue declined 23% in the fourth quarter compared to a year earlier. Gannett’s share value has plunged 90.1% over the past four years.

Lee’s stock is almost worthless, having declined 98% to pennies a share over the same four-year period. Journal Communications Inc., publisher of the state’s flagship daily, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, is mired in its own discombobulating stock plunge. (See sidebar.)

Layoffs and buy-outs became rife industry-wide. One tabulation counted almost 16,000 jobs lost in the U.S. newspaper industry in 2008, at least 200 among Wisconsin papers. (I left Isthmus as part of the paper’s retrenchment.) The cutbacks have come at exactly the same time workloads for remaining reporters and editors have kicked up with the need to expand web products.

Big surprise: News coverage is suffering.

Veteran investigative reporter Andy Hall attended the annual meeting of the Wisconsin Newspaper Association in late January in Green Bay. He was disturbed by what he heard.

“Wisconsin journalism is in big trouble,” he told me. “Editors described with some alarm the ways in which cutbacks are decreasing their ability to monitor local governments across the state.”

Hall heard editors talk about the large numbers of town, village and school boards going virtually uncovered in smaller communities across Wisconsin. “The problem has worsened as a result of the economic troubles,” he added.

The problem is even felt in Madison, where the number of reporters covering the Capitol and state issues has plummeted over the years. “We’ve really noticed it,” said Charity Eleson, executive director of the Wisconsin Council on Children and Families.

“The challenge from our perspective is that we work on issues that are complex, and the real value of a newspaper story done by a knowledgeable reporter is that he or she can help the public really understand what’s going on,” Eleson explained.

Her group has begun experimenting with videos and its own blog, “but it won’t compare to a thoroughly reported investigative story,” Eleson said with a sigh. “I’m 52. I’m part of the generation that grew up on newspapers. I like print. I realize newspapers have online versions, but it’s not for me.”

Eleson’s comments illustrate one of the central dilemmas newspapers face. Their most loyal readers, invariably older, are less likely to be web creatures, while younger readers have swung decisively to the web. The Pew Research Center, for example, found in December that 59% of Americans under the age of 30 chose the Internet as their preferred choice for news; only 28% named newspapers.

Count Madison Mayor Dave Cieslewicz among those grumpy baby boomers.

“What’s going on is scary to a guy like me,” he said. “I disagree with reporters and editors all the time, but we share a common language and a common set of rules and standards. I can call up and complain whether a story was worthy of page one or about what Dean Mosiman [the city hall reporter of the Wisconsin State Journal] wrote in his lead.

“But in the wild west of the Wikipedia world, where anyone can throw anything up on the web and see where it lands, you don’t have that professionalism,” the mayor said. “There is no editor challenging what a reporter has written. I really regret the weakening of standards.”

Cieslewicz, a fine writer himself, has begun blogging on the city’s website. He will probably get roasted for claiming web postings are unvetted (bloggers would argue that the back and forth of community comment is a better mechanism for ensuring accuracy than a gimlet-eyed editor). But Cieslewicz is on to something when he talks about the enduring importance of serious reporting of complicated topics.

Amateurs can’t do it.

Oh, sure, there’s a case to be made for the wisdom of crowds and the accretion of information online. But amateurs can’t do serious investigative reporting any more than they can remove a gall bladder or drop a new engine in a car.

Editors and reporters know this, and it drives them wild with despair. They know that their work remains critical to their communities’ wellbeing we and that their original journalism is still avidly consumed online. Above all, they know that good, solid reporting remains an extraordinary asset in an online world brimming with wheat, chaff, chaos and lunacy.

But the killer is that no one seemingly wants to pay for their work. Even worse, so-called aggregator news sites run by Google and Yahoo and popular sites like Drudge and Huffington Post wind up selling ads around the links to their stories.

The result has been predictable. While most newspapers remain profitable, plummeting revenue has triggered wave after wave of staff buy-outs and layoffs, taking an undeniable toll on newspaper quality. This is a problem.

John Morton, the dean of newspaper industry analysts, told me that he worries that many newspapers are hurting their chances for the web by reducing their news holes and slashing their newspaper staffs.

“In effect, they’re diminishing the stature of their brand name and their stature in the marketplace,” he said. “Those are their most valuable assets – and that’s what they need most to move on to the Internet, which is still very much in its infancy.”

If a successful business model is to be found online for newspapers, Morton warned, “what they’re doing now will make it more difficult to establish.”

Not all is doom and gloom. For all their travails, newspapers are starting to “get it” online. They’ve moved beyond just posting their stories (which was a struggle in itself), to shooting videos, blogging, offering interactive databases (how gutsy of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel to provide searchable health-inspection records for local restaurants) and presenting mixed-media stories.

In this new media world, you now find an old-school cop reporter and feature writer like the Wisconsin State Journal’s George Hesselberg shooting and editing a video about UW-Madison students watching President Obama’s inauguration.

In Appleton, Post-Crescent business writer Maureen Wallenfang’s “Buzz Blog” averages 689 page views per hour for her chatty items on local commerce, according to publisher Genia Lovett. On Friday nights, the paper’s sports staff sends text messages reporting prep scores to high school sports fans.

The Journal Sentinel has encouraged its sports writers and arts reviewers to blog. “You can put your reporter right in the center of a community of interest, whether it’s the Brewers, the Packers or the arts,” said managing editor George Stanley.

Visual arts critic Mary Louise Schumacher uses video and photo slideshows to discuss art exhibits. On fast-breaking stories like last summer’s floods, the paper taps into on-the-scene observers to round out coverage and provide details on its website, JSonline.com.

The Janesville Gazette has fully embraced the multi-platform approach to news coverage. Editor Scott Angus pointed to reporter Stacy Vogel is a case in point. Vogel will cover a night meeting in Edgerton or Milton, write up a one- or two-paragraph summary for immediate posting on the paper’s website, file her story for the next day’s paper, and tape a 30-second summary for WCLO, the radio station owned by the paper’s parent company. Some mornings she’ll be interviewed for a longer radio report put together by the paper’s multimedia editor. Or she’ll answer questions on talk-show host Stan Milam’s morning show.

The mantra of Angus and all the other editors and publishers is virtually the same: We cover our town better than anyone else, and if our paper is going to succeed in the new online media world, it’s because we provide authoritative coverage.

The problem is that online is proving a bust for newspapers. This may be the most dire news of all.

Newspaper websites like JSOnline and Madison.com tend to dominate their community’s online action. Nationally, The New York Times, USA Today and the Wall Street Journal host three of the most popular news sites around. But poke beneath the surface, and there is disappointment aplenty. Newspaper websites just don’t make much money.

They generated 7% of all newspaper ad revenue in 2007, according to Alan Mutter, the Newsosaur blogger (who’s a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and a former newsman). This is chump change, not even close to supporting an existing newsroom. Fans of the “paperless newspaper,” Mutter warns, “recklessly disregard the economic realities of the publishing business.”

These realities include the fact that the vast majority of online revenue is “upsells” to the web added on to a print-advertising contract. It takes “a tremendous leap of faith,” he says, to think these advertisers would stick with the website once the print product was shut down.

Mutter drills deep into the viewership data and is unimpressed with what he finds. “Young consumers, who represent the future of any media business, spurn newspaper websites,” he writes. Site visits don’t parse well either. They average only about 90 seconds a day at newspaper sites, and even worse after the conclusion of an avidly followed presidential election – about 27 seconds a day in December.

As wounded as newspapers are, Mutter concludes that the ones that still eke out a profit can’t afford to make the jump to online-only publishing. That is, not until fundamental online economics change, like charging for content.

Micropayments are the great dream of newspapers – that avid readers will willingly pay a nickel or a dime for a story, or $2 a month. In other words, salvation is an iTunes for pixel-stained wordsmiths.

Every few years this vision has re-emerged with almost a religious certainty as the road to prosperity. Most recently, Walter Isaacson writing in Time made the compelling case that newspapers have to stop giving away their best work.

Isaacson rightfully pointed out the paradox that we live in a world where kids think nothing of paying the cell phone company up to 20 cents to send a text message, “but it seems technologically and psychologically impossible to get people to pay 10 cents for a magazine, newspaper or newscast.”

He remains convinced that a “pay-per-drink” model can succeed if it’s simple and relatively painless to use. But skeptics don’t see it happening. With iTunes, of course, subscribers are buying a song they can play over and over again, while most newspaper stories, even the Pulitzer Prize ones, are seldom read more than once.

News stories, by their very nature, have a gnat’s lifespan. Who’s willing to pay for something so transitory when the web offers an unending supply of free new information?

Jim Baughman, the journalism prof, makes a beguiling argument that the very cacophony of web voices may rebound to the benefit to a smartly written and edited newspaper.

Information overload isn’t a new phenomenon in American history, he pointed out. In earlier periods of information glut, pioneering publications like Time magazine in the 1930s explicitly set themselves up as a guide to steer readers through the uproar of new media voices.

“Time wasn’t a historical accident,” Baughman said. “It was perfectly timed in it its original mission to tell the middle class ‘Here’s what happened last week. Here’s what you need to know.” It was a brilliant idea.

“This could be the salvation of American newspapers,” Baughman ventured. Newspapers could market themselves as a source for authoritative news and analysis – as a responsible guide through the web’s information funhouse.

“This is an argument that newspapers should make forcefully, even obnoxiously,” he said. “That’s exactly what Time did – it exploited the public’s anxiety over the information glut.”

Of course, readers were willing to pay for Time. Whether they would pay for any of Wisconsin’s 32 dailies is another question. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, with its commendably heavy investment in investigative journalism, is operating at a quality level unmatched by any other Wisconsin daily. Yet the paper is reeling financially, having frozen staff salaries and cut its dividend.

The bitter lesson is that quality doesn’t necessarily sell online. Not yet at least. Baughman acknowledged as much. “That’s my rosy scenario,” he said of the Time model. “My worst-case scenario: All newspapers disappear.”

Whoa! Really?

He amended his answer to say that he expected more newspapers to cut back from daily publication to three or so editions a week as they plot an eventual move to web-only publication. Other papers will simply wither away and die.

“Daily papers as we know them today may not be around in five or ten years,” Baughman said.

Of course, his first words to me were: Nobody knows anything about the future of journalism. Including me after 35 years in the business. But I have to wonder if the industry’s collapse isn’t even more imminent.

Marc Eisen, a freelance writer and editor, is the former editor of the Madison alternative-newspaper Isthmus.