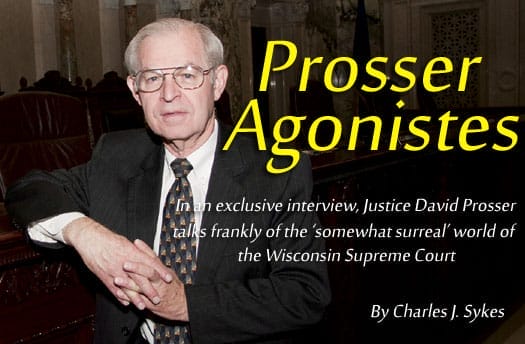

In April, David Prosser was re-elected to a 10-year term on the Wisconsin Supreme Court after a campaign in which he found himself at the center of the state’s tumultuous political divide. Unions and national liberal organizations targeted Prosser, seeking to turn what had been a sleepy re-election bid into a referendum on Gov. Scott Walker’s budget repair bill.

The day after the election, his opponent, JoAnne Kloppenburg, declared herself the victor despite having a mere 204-vote lead in the unofficial tally, only to see that lead overturned when uncounted ballots from heavily conservative Waukesha County gave Prosser a lead of more than 7,000 votes.

Prosser’s victory (after a lengthy and expensive recount) has not, however, quelled the increasingly heated and personal controversies on the court. In June, as justices argued over the fate of the collective bargaining bill, there was a physical confrontation between Prosser and Ann Walsh Bradley. Bradley accused Prosser of putting her in a “chokehold,” a charge disputed by other witnesses and by Prosser, who said that Bradley had initiated the confrontation and had charged him. After a lengthy investigation, a special prosecutor declined to issue any charges in the incident.

Because that incident was still under investigation by the state Judicial Commission at the time of this interview, we did not address that issue in what was otherwise a wide-ranging discussion on the campaign and the state’s high court. I sat down with Justice Prosser in mid-October at the offices of the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in downtown Milwaukee.

[Sykes] During the controversy over the collective bargaining bill you said you had lost confidence in the leadership of Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson. When did you lose that confidence?

[Prosser] The chief has been a divisive force on the court for many years. But she became more arbitrary when she gained a working majority on the court during the 2004-’05 term.

We live now in a somewhat surreal situation. The chief justice can be a brilliant judge and a skillful, visionary leader one day, but a petty, divisive troublemaker the next. In fact, this dichotomy sometimes appears several times during the same day.

Are you talking about substantive legal issues or personal pettiness?

Both. I have never worked in a situation like this. The chief justice is vested with a leadership position because of her seniority. I respect her for her intellect, her ability and her hard work; yet I often wonder what on earth she is thinking, either substantively in terms of the ramifications of her decisions on society, or professionally in terms of her interpersonal relationships with other members of the court.

You’ve been on the court for more than a decade. Has the level of civility gotten worse?

Most people are familiar with the case Brown v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court decision desegregating schools. Initially, the Supreme Court was not unanimous. There were divisions among the justices. Chief Justice Earl Warren persuaded his colleagues that there are some situations in which the court really must be unanimous. Sometimes the court has to present a united front because the issue being decided is vital to the entire country.

This unity approach almost never succeeds in the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Why not?

The chief justice believes that a justice need not ever surrender his or her individuality for the larger interests of the institution. There are times I think the court should speak with a united voice, even though I may not agree with the result.

The chief justice does not agree with this unless her view happens to be the majority view.

This disagreement is symbolic of the divisions within the court. In my view, the court, as an institution, is far more important than the prestige or batting average of any individual justice. Some of my colleagues may not see it that way. Some of my colleagues cannot stand to lose on any issue.

There are ways that justices can vigorously disagree with each other without becoming personal and petty in the way they discuss judicial matters or the way they write opinions. On almost all occasions, opinions can be written without questioning the intelligence or integrity of colleagues on the court. It is very rare that an issue is so critical that it justifies a public attack on a colleague’s integrity. Attacks of this nature damage the reputation of the whole court.

Obviously on a court the ability to disagree on the law and have civil relationships is crucial. But the court seems to have moved from trying to persuade one another to trying to destroy one another. Does that describe the situation on the court today?

Unfortunately, it does. And it has created a very difficult working environment. I’m not sure how to repair it, except for justices to do a lot of soul-searching and modify their own conduct.

Shortly after I was appointed [1998], the court approved open administrative conferences. The objective was to provide transparency and promote good behavior among the justices. Early on, it seemed to work pretty well, and I was happy to trumpet this Wisconsin innovation. Now, however, these conferences can be seen on the Internet, and the conferences have become a forum to highlight ideological objectives and to put down other members of the court. To see justices duking out political issues this way does not enhance the image of the court. The workings of the court may be overexposed.

Today there are people who believe the problems of the court should be addressed primarily by changing procedures or rules. Some changes would be useful. But it is hard to achieve a smooth operation when some members of the court have no respect for their colleagues and are prepared to do almost anything to prevail over them and discredit them. This is not an atmosphere in which it is easy to work together.

How would you describe the mood on the court, behind the scenes these days? Given everything that has gone on, how do you interact with one another?

Relations are relatively cordial in public but icy in private.

More than once, a word of greeting has not been acknowledged. To illustrate, the first day of the term, I saw Justice Bradley in the hallway and passed her and said, “Hi.” There was no response. The same thing happened with the chief justice.

I was leaving the Capitol one night and came to a doorway in the building just as the chief was coming in. She sort of gasped in surprise when she saw me. I said, “Hi, Chief.” There was no response. What I’m saying is that the person who calls me “Dave” in an open meeting may not speak to me when we are alone.

Should the chief justice be chosen on the basis of seniority? Should there be an alternative system for selecting the chief justice?

I think we are going to have to develop an alternative to the present system. People who dispute that conclusion have to remember that if I were determined to serve on the court as long as I could, I might eventually become chief justice by virtue of seniority. Then the defenders of the present system might say, “That’s crazy! That maniac should not be the chief justice.” We need to find a way to choose a leader who will work consistently with all members of the court and all members of the judiciary.

Another principle ought to be considered. Lord Acton taught us that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Frankly, the longer someone serves as chief justice, the more arbitrary that person is likely to become. The person may begin to see the court as some sort of personal institution and fail to distinguish self-interest from the court’s interest. I think there ought to be term limits for any chief justice.

Could you talk about the politics of recusals and how that has changed in the recent era?

It has become very clear that some litigants and third parties will target justices in an attempt to remove them from specific cases and change the composition of the court. This can be accomplished by engineering a public furor suggesting that a justice cannot be impartial.

Inside the court, the chief justice suggested that the court, as a whole, ought to be able to second-guess a justice’s decision on recusal and remove that justice from an individual case. Holy cow! In view of recent events, it is not hard to imagine how incendiary that power would be and how it could be abused. The threat that a majority of the court could vote to exclude a justice from decision-making would destroy personal relationships and create incentives to use the power for political purposes.

Four members of the court ultimately issued an opinion disavowing an ad hoc power of recusal. We had to overcome massive resistance. Such a blunt instrument is very different from a justice coming to me and saying, “Dave, I really don’t think you should sit on this case and here’s why.” I can respect that. That is very different from saying, “I have decided to remove you from this case.”

A lot of people have looked at the dissention on the court and said this makes a good case for making the judiciary appointive. Should we elect judges?

Yes, I think we should elect judges. I wouldn’t change the whole system. Part of the current problem stems from the guerrilla tactics being used by third parties to affect judicial elections. Their short-term objective may be to elect or defeat a particular candidate, but the longer-term objective, for some, is to discredit judicial elections generally and to push public opinion toward judicial appointments.

Some people argue that the case for judicial elections is simplistic and outmoded. But I like the general democratic theory that people should be able to choose their public officials and make them answerable to the public at reasonable intervals. Ultimate accountability is very, very important in state courts.

Justices regulate the bar and the practice of law. They make many rules. They have a tremendous impact in Wisconsin on individuals, families, the economy, public safety, education and virtually every area of life. Judges exercising great powers should be subject to periodic review by the people, just as the actions of individual citizens are often subject to review by the courts. Judges must have the independence to fearlessly apply the law, but they should never become disconnected from the citizens they serve.

Were you surprised during the campaign when you became the lightning rod and suddenly became a symbol of everything that was happening in the state?

I was shocked, but the shock wore off quickly. Two or three days into the demonstrations at the Capitol, a good friend of mine who is a nurse informed me that she was one of the demonstrators. She didn’t strike me as a typical demonstrator. She also gave me a piece of literature that was being handed out. It said that the two biggest enemies of labor in Wisconsin were Scott Walker and David Prosser. When I saw that piece of literature, I knew right away that something was up.

Before the campaign, you had a reputation as a conservative but independent judge. What was your reaction when you saw hundreds of thousands of dollars of television ads saying “Prosser = Walker”?

Well, I’m familiar with campaign distortion. The truth of the matter is that I had no clue of what was coming from the governor. My intent was to run on my record as a justice, which is a conservative record but not a record on the political fringe. I am at the center of the court. I believe strongly that the court should apply the law, apply statutes and contracts according to the written language, but also be very conscious of the implications of our decisions.

Suddenly, I was being painted as a puppet of the governor. The evidence provided was that he and I voted the same way 95 percent of the time when we served together in the legislature. Well, I was the speaker at the time. From my perspective, he was voting with me. I wasn’t voting with him (laughs).

The governor does his own thing. I respect him. I like a lot of what he has done. But we are different people and independent of each other, especially in court. My job is not to support the governor; my job is to follow the law.

[During the campaign, Prosser’s opponents ran ads attacking his handling of a case of sexual abuse by a priest in the 1970s when Prosser was a district attorney.] When the victim in the sexual abuse case called on your opponent, JoAnne Kloppenburg, to repudiate the ad, were you surprised that she refused to disavow the campaign?

No. I wasn’t surprised because she was part of a take-no-prisoners campaign. I don’t think she appreciated the damage that was being done to me personally or internalized how she would have felt if she had been in my position. This was a failure to connect in a personal way with a person who was going through the same campaign she was going through. So I wasn’t surprised, but I thought her response made her look bad and very cold.

The fact that the victims of the sexual assault came forward was so extraordinary and unexpected that it made me feel I could still win the election.

Was there a sense of vindication for you?

Oh, yes. Absolutely.

There was also an allegation that you had a secret meeting with the governor shortly after the election, which was part of the formal complaint from the Kloppenburg campaign. Were you satisfied with the way the investigation into that charge was handled?

That allegation was totally false.

I told reporters it was totally false — that it never happened.

When attorney Tim Verhoff was hired by the Government Accountability Board to investigate the many charges made by the Kloppenburg campaign, I went to Kevin Kennedy, the board’s executive director, and asked the GAB to investigate the specific accusation against me. He said he had not thought to do that but came around and said he would. Later, Tim Verhoff called me in. We had a good meeting. I answered every question he had. The accusation is discussed in the GAB report.

Unfortunately, the report does not come to a conclusion that rejects the accusation. The report does not indicate that the accuser was ever interviewed.

This is incredibly frustrating. These days, when a false accusation is made, it is seldom fully corrected. It remains out there: on the internet, in print, in people’s memory. How does a person restore his reputation after a false charge is made?

So where does someone go to get their reputation back?

I don’t know. I believe completely in free speech — that is the essence of our society. But somehow, before people make wild charges, they should understand that there will be a day of reckoning for them — that they will be discredited for knowingly making false charges. I’m not sure how to do that. For a public figure, a libel suit does not provide an answer.

I think over time a person like myself will be able to restore his credibility, so long as the truth has a chance to catch up. This is much more difficult when there is a new attack every week. I haven’t been able to see light at the end of the tunnel yet, because there is just one falsehood, one misrepresentation, after another.

In the end, do you think you’ll get your reputation back?

Yes.

Were there times during the campaign and afterwards where you thought, this is just not worth it?

(Laughing) More than once I thought to myself: “This is tough,” and “Can it get any worse?” On the other hand, I’m a fairly low-key guy. I’ve never been confused with Mr. Charisma. When I ran for Congress in 1996, I was beaten by a television news anchorman who drew more attention when he walked around with his dog than I did for anything I accomplished in 20 years of public life. So I wasn’t a celebrity over most of my political life.

Now, however, things have changed. People came up to me during the campaign and said, “I’m praying for you.” It happened all over Wisconsin. Even now, people stop me to wish me well and urge me to keep fighting. Today, for example, a man walked up to me in a McDonald’s on the south side of Milwaukee. He said he was a big supporter. We had a great conversation. These gestures mean more to me than I can ever tell you.

The day after the election, did you think you’d lost?

Let me say, Charlie, that my staff never told me before the election how far down I was. They did not level with me because they knew that really bad news does not help the candidate’s attitude. On the other hand, I’m not a total dolt. I knew it was a very tough election and that I could lose. It heavily depended on turnout.

On election night, as each precinct came in, we were up and down. At midnight, we were still ahead, but it was pretty clear when the calendar flipped over to the next day, that it was not likely we were not going to pull it out.

I’ve won elections many times, but I have lost elections, too. Twice. I know there is life after an election defeat. So I thought, “If it’s only 200 votes, anything can happen. The count can change.” So I really wasn’t that down as though it was all over.

What would have happened to the state of the law and the state Supreme Court if you would have lost this election?

It would have been a vindication of the worst kind of judicial politics. It would have been a total encouragement of the forces who want to take the Supreme Court in a radically different direction. It would have sent shock waves to the business community and the law enforcement community and the social conservative community in the state that the court would go in a very, very different direction.

I respected my opponent in the campaign as a very intelligent person. She’s argued before the Supreme Court and she’s done a good job. But there is an ideology driving her that makes her very different from me, and I think she would have been heavily influenced by the chief justice and Justice Bradley.

I really don’t mind if someone has a very different ideological perspective than mine if the person is open-minded and willing to listen — if the person is strong enough to be an independent thinker. But it must be very disconcerting for litigants to look at the court and be able to predict most of the votes before a case is argued. I like to be a little unpredictable and to look at each case independently.

Do you have any regrets?

Of course I have some regrets. I have a big enough ego to read the newspapers and the Internet. My goodness, I’ve been attacked editorially in The New York Times! How does a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice rate that attention? I’ve received communications from Russia demanding that I resign! When I was accosted by a television reporter and cameraman who jumped out in front of me from behind a corner, I obviously did not handle that well.

When I walk out of the Capitol and see scrawled on the sidewalk, “Prosser should be in jail,” or when I run into somebody and they literally scream at me and pursue me, yes, I have some regrets.

I would have more regrets if other people were not so generous and supportive and encouraging and if I did not think that in the end I will come out all right. I have one of the greatest jobs in the world, and I am not going to let a bunch of irrational haters drive me out of it.

Charles J. Sykes is editor of Wisconsin Interest.