“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

— First Amendment to the United States Constitution

On Jan. 21, Madison’s Capitol Square was gripped in the dark deep freeze of a lonely Friday evening. On the coldest day of the year, the state employees who remained downtown had retreated to the cozy warmth of the trendy boites for their after-work glasses of Chardonnay.

Huddled against zero-degree temperatures driven by a biting wind, 40 hardy souls clustered outside the State Street entrance to the Capitol, hoisting their hopes aloft in the form of homemade signs.

More daunting than the bitter cold weather, their objective was to amend the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution for the first time in its 220 years.

The Madison rally was one of 41 around the nation that day protesting a U.S. Supreme Court decision on its one-year anniversary: Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

No high court decision has so enraged — or energized — America’s left. At the Madison protest, fiery red-haired Green Party activist Ben Manski called it the worst ruling since Dred Scott enshrined slavery in 1857. It is a comparison made by opponents from Keith Olbermann to Florida firebrand Alan Grayson to Madison-based Progressive magazine editor Matthew Rothschild.

They are convinced that the Supreme Court has given “a green light to a new stampede of special-interest money in our politics,” as President Barack Obama said shortly after the decision was rendered.

The ruling overturned the McCain-Feingold campaign financing limits enacted eight years earlier, thus permitting corporations unlimited spending on not only issue ads but for supporting candidates for federal office if they did so independently of their campaigns.

Critics have coalesced behind a nationwide movement calling itself “Move to Amend,” with Madison as one of its epicenters. Member organizations include activist groups such as the Green Party, the National Lawyers Guild, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the anarchic Ruckus Society, the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, and People for the American Way.

They will gather in Madison for a national convention Aug. 24-28 to plot strategy. Kaja Rebane, a former co-president of the UW-Madison Teaching Assistants’ Association, is one of the national leaders. She says the coalition is promoting advisory referenda all across the country. It would ask:

“Should the United States Constitution be amended to establish that regulating political contributions and spending is not equivalent to limiting freedom of speech by stating that only human beings, not corporations, are entitled to constitutional rights?”

A version will appear on the April 5 ballot in Dane County.

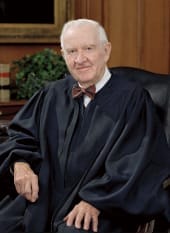

The movement takes as its touchstone the minority opinion of Justice John Paul Stevens: “In the context of election to public office, the distinction between corporate and human speakers is significant. Although they make enormous contributions to our society, corporations are not actually members of it. They cannot vote or run for office.”

“We want to clarify once and for all,” says Madison activist Grant Petty, “whom the Bill of Rights applies to — flesh-and-blood human beings, not fictitious legal entities whose sole original purpose was to facilitate business dealings.”

How about unions? “We don’t have a union personhood problem,” Rebane answers. “We do have a corporate personhood problem.”

The Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission case was decided by a 5-4 vote. At issue was whether a conservative nonprofit group called Citizens United could air a 90-minute movie critical of Hillary Clinton during the 2008 presidential campaign.

The Federal Elections Commission argued that doing so violated the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. The law, commonly known as McCain–Feingold, prohibits corporations from delivering political messages 30 days before a primary or 60 days before a general election.

During oral arguments, the Justice Department said that yes, even a 500-page book could be banned if any corporation was involved and it bore one line of candidate advocacy.

“The government claimed this power extended not only to for-profit corporations, but to non-profit corporations such as the Sierra Club, the NRA, your local Chamber of Commerce, or local humane society,” former FEC Commissioner Bradley Smith wrote on the Politico website.

That theory, Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. said in the majority opinion, “would allow censorship not only of television and radio broadcasts, but of pamphlets, posters, the Internet, and virtually any other medium that corporations and unions might find useful in expressing their views on matters of public concern.”

For the majority, the notion that “corporations aren’t people” and have no First Amendment rights just didn’t mean much when it came to the practicalities of free speech.

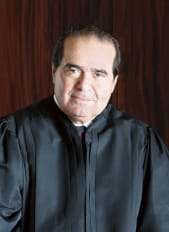

“Surely the dissent does not believe that speech by the Republican Party or the Democratic Party can be censored because it is not the speech of ‘an individual American,’” Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, explaining that an “individual person’s right to speak includes the right to speak in association with other individual persons.”

Scalia said that the First Amendment means what it says: “The amendment is written in terms of ‘speech,’ not speakers. Its text offers no foothold for excluding any category of speaker, from single individuals to partnerships of individuals, to unincorporated associations of individuals, to incorporated associations of individuals….”

This argument sails right by Mike McCabe of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign. “Our nation’s founders never said money is speech,” he cried out post-decision.

“They never said corporations are people. There comes a time when the actual words of the founders must be respected and honored.”

One might ask: If money is not speech, then why is McCabe begging for contributions? His website informs visitors: “Your donation…helps make our work for clean government and real democracy in Wisconsin possible…. There are three ways to give.”

Corporations make for swell boogeymen on our college campuses, in liberal towns like Madison and in Michael Moore movies.

In a statement to the left-leaning website Forward Lookout, Dane County Board chairman Scott McDonell warned, “Corporate interests may have infiltrated the Supreme Court and pulled the wool over Congress’ eyes.” Cue the Mission Impossible theme song.

“Their only stake is profit, irrespective of the interests of the citizens of Wisconsin,” says Petty, a UW-Madison meteorology professor.

Never mind that profit could very well be of interest to many citizens of Wisconsin — employers, employees, and retirement annuitants alike.

“There is a popular sense that corporations are evil and somehow have unlimited resources by virtue of their status as corporations,” says Marquette law professor (and Wisconsin Interest columnist) Rick Esenberg. “In fact, corporations are merely associations of one or more people formed to undertake a particular activity.”

It is surprising and a little discouraging that many news media voices are riding the First Amendment to deny that protection to others. John Nichols used the resources of Capital Newspapers Inc. to write on The Capital Times website that Congress should “amend the Constitution to fight corporate power.”

Chief Justice Roberts saw the irony. Such limitations, he wrote for the majority, “would empower the government to prohibit newspapers from running editorials or opinion pieces supporting or opposing candidates for office, so long as the newspapers were owned by corporations — as the major ones are.”

Do journalists have more First Amendment rights than the rest of us? If we don’t own a press, may we rent one? Justice Kennedy wrote that in an age of blogs and tweets, everyone is a journalist.

When all is said and done, the court’s decision is clouded by misconception.

Even President Obama claimed the decision overturned the prohibition against corporate donations to candidates enacted in Teddy Roosevelt’s day. That misstatement — by a Harvard Law School graduate, no less — prompted Justice Alito to mouth “Not true” during the 2010 State of the Union address.

Corporations are still prohibited from contributing directly to a candidate’s campaign, although, admittedly, their ability to spend independently compensates. The Supreme Court’s precedent for banning corporate independent expenditures dates back only to 1990’s Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce.

Too much money in politics? That did not bother Barack Obama when he unilaterally blew past public financing for his 2008 campaign so he could exceed its spending limits. The columnist George Will famously calculated that the $5.3 billion spent in the 2008 congressional and presidential election cycle was one billion less than Americans spend on potato chips per year.

“The First Amendment does not permit government to decide the ‘proper’ quantity of political speech,” Will wrote.

Nor does the biggest spender always win. Take the 2010 governor’s race in California. Meg Whitman lost the most expensive non-presidential race in U.S. history despite spending over $160 million to $40 million for the winning Democrat, Jerry Brown. Unions poured in another $28 million to independent expenditure groups on Brown’s behalf.

In Democratic New Jersey, incumbent Gov. Jon Corzine outspent his Republican challenger Chris Christie by a 3-to-1 margin — $23.6 million to $8.8 million — and still lost.

“In practice, Citizens United worked,” former FEC chairman Smith wrote in his Politico piece. “The elections of 2010 illustrate the benefits of a freer political marketplace. The campaign was one of the most issue-oriented in memory. More races were competitive than in any election since before the Federal Election Campaign Act was passed.”

The critics understand the difficulty of amending the U.S. Constitution, requiring, as it does, two-thirds votes in each house of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures. Over 10,000 amendments have been proposed since 1789; only 27 have succeeded.

“No one has any illusions that it will be easy, as anyone who experienced the heartbreak of the Equal Rights Amendment can attest,” editor Rothschild wrote.

Even more daunting, only four constitutional amendments have reversed Supreme Court opinions, “and most had to do with expanding rights, not restricting them,” observes UW-Madison political science professor Donald Downs.

Still, there may be latent public support for the amendment. An August 2010 Survey USA poll found that 77% of voters see corporate spending in elections as akin to bribery.

Nearly 80% of voters feel that corporations have an unfair advantage, according to a public opinion poll released in January by the Democratic polling firm Hart Research Associates.

Whether that translates to active support for a constitutional amendment is another question.

The movement to amend the Constitution poses a disturbing question: When did America’s political left become the enemy of free speech?

Before Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s Labourites seized the commanding heights of the economy. Those who support “Move to Amend” want to control a commodity much more valuable than coal. They’re wagering that citizens — “restive, frightened and easily manipulated,” Capital Times columnist Bill Berry called them — cannot be trusted to sift and winnow the truth for themselves without the careful ministrations of good progressives to regulate, ration, and redistribute political speech.

“This movement implies a distrust of citizens and wide-open free speech,” Downs agrees.

“I would put ‘Move to Amend’ in the ‘be careful what you wish for’ category,’” says UW-Madison journalism professor Robert Drechsel.

“Some of the very organizations supporting the effort — not to mention the foundation through which donations are to be sent — operate in corporate form,” he points out. “So do innumerable other ideological organizations and journalistic organizations. I can’t believe that Move to Amend’s supporters intend to put their own speech rights in jeopardy, but that could certainly be one outcome.”

David Blaska has been a Capital Times reporter, gubernatorial aide to Tommy Thompson and Dane County supervisor. Blaska’s Blog is a popular feature at TheDailyPage.com.