The revolution came to Madison in February, but not the one you think.

Sure, Gov. Scott Walker’s efforts to roll back a half-century of labor legislation and the ferocious liberal backlash were earthshaking events. But the outcome of this epic struggle awaits a last act.

No such uncertainty marks the digital revolution. New media played a crucial role in both organizing the Capitol protests and in covering them. The digital future arrived on the wings of text messages, cell-phone photos, flip-camera videos, Facebook posts and Twitter tweets.

“It was a turning point,” says Dhavan Shah, a University of Wisconsin-Madison journalism professor. The protests against ending most collective-bargaining rights for public employees “demonstrated the potential power of social media as a mobilizing force. We’ve seen a season of that literally across the globe.

“The parallels aren’t as great as some people would like to think with what happened in Egypt,” he says, citing how the Twitter generation deposed strongman Hosni Mubarak. “But certainly we saw evidence of how information can move laterally between trusted networks of people rather than coming top-down from mainstream media or even from elite political bloggers.”

So how did the revolution play out? Consider the experiences of three players in the new-media order:

* Steve O’Neill, a former union organizer for the butchers, was checking Facebook and his labor websites early evening on March 19 when he was stunned to read that the state Senate had unexpectedly voted 18-1 to gut collective bargaining for public employees. Within 15 minutes, a fired-up O’Neill had left his Madison home and was surreptitiously climbing through a basement window to enter the supposedly locked-down Capitol.

“That night pretty much opened my eyes,” says O’Neill, 62, who notes his days as an avid newspaper reader are over. “I knew if I wanted to get timely, accurate information, I had to go online to find it.”

O’Neill says he came to Facebook “totally by accident” when he signed up to get the details of his 40-year high school reunion three years ago. Now he’s a convert: “It cuts out the middle man. You don’t have someone filtering your information.”

* If O’Neill was a reluctant convert, young people like Alex Hanna, 25, turned to social media within a nanosecond. As a leader of the Teaching Assistants Association on the UW-Madison campus, Hanna briefed his nearly 3,000 members through email, tweeted comrades to coordinate student speakers at a Joint Finance Committee hearing, texted other TAA leaders to plot strategy, used Facebook to promote major protests and, last but not least, set up the Defend Wisconsin website to post press releases, blog reports and a calendar of events.

Tech-savvy TAA activists like Hanna emerged as key leaders in the protest. But Hanna, who’s a sociology graduate student studying social movements and social media in the Middle East, is wary of the hype. He says that new media is simply a tool to be used in a broader political strategy.

And he doesn’t buy any comparison to the uprisings in the Muslim world. “Social media means something very different in an oppressive state,” he says. “Nobody got killed in Madison.”

* A thousand miles away, Charles Hughes, a UW-Madison doctoral candidate in history, was wired into the events in Madison even though he was in Washington, D.C., on a research fellowship.

“I member walking around the National Museum of American History getting first-hand reports on Facebook, a few on Twitter, even before the national news media was reporting the story,” he says.

“A lot of my friends were among the first people in the Capitol,” Hughes says, recalling their messages — everything from the mundane (“We need water”) to the tactical (“We need people here, in this room, right now.”)

“It was nice having this direct line into the action,” he says. “Even though I was on the East Coast, I felt part of the information network.” But the experience also left Hughes disconcerted with how the protests were portrayed by TV news. “They weren’t covering the story I heard from the people on the ground,” he says. “MSNBC was just as bad as Fox. For anyone hooked into the digital media world, they were just missing a whole lot of the story.”

And that brings us to the second front of the revolution: News coverage of the Capitol protests was transformed by the digital advance into the 21st century.

Like never before, non-traditional news sources helped drive the story’s at-times conflicting narratives. Partisans, activists, ordinary citizens and even pranksters were all enabled by digital media.

“We hold up our smart phones and say, ‘If it’s not happening here, you’re not reaching anyone under the age of 30,” says Brian Fraley, communications director of the conservative MacIver Institute.

“Social networks aren’t just for Justin Bieber fans,” he says. “They’re how people share their ideas and concerns about public policy. … Our philosophy is that we can’t control how people get information, so we put it out there on multiple platforms — Facebook, Twitter feeds, the Web.”

Time and again, non-traditional news sources such as MacIver and Media Trackers broke and publicized protest-related stories. As Shah, points out, those reports quickly became the fodder of mainstream news reports.

Talk show host Charlie Sykes (who is editor of this magazine) publicized the vile threat that state Rep. Gordon Hintz (D-Oshkosh) made to state Rep. Michelle Litjens (R-Oshkosh) — “You’re fucking dead” — on the Assembly floor. Sykes’ blog post garnered more than 200,000 hits and broke into the national news.

Another Sykes post — exposing a strong-armed union attempt to pressure M&I Bank to support the protesters — drew more than 250,000 hits after it was linked by Matt Drudge’s powerhouse site.

MacIver and UW-Madison law professor Ann Althouse, whose blog has a national following, both posted eye-opening videos of Madison doctors freely writing medical excuses for teachers who skipped work to protest at the Capitol.

Freelance photographer Phil Ejercito’s dramatic video captured Capitol protesters approaching mob-like behavior as they pursued state Sen. Glenn Grothman (R-West Bend) as he tried to enter the locked-down Capitol. Ejercitos’ 12-minute video, viewed more than 190,000 times on YouTube, shows archliberal state Rep. Brett Hulsey (D-Madison) stepping in and defusing the confrontation as he declares the conservative Grothman to be his friend and urging the hecklers to be “peaceful and respectful.”

In a footnote to the ridiculous, blogger Jack Craver, who posts as “The Sconz,” garnered more than 240,000 YouTube views for his serendipitous video of a failedDaily Show bit that featured a camel and Comedy Central’s John Oliver. Plans for Oliver to mimic whip-wielding Mubarak defenders (they rode camels through crowds of Egyptian protesters) came undone when the poor camel slipped on the ice and became entangled in temporary fencing on the Capitol grounds.

But the most notorious of all the acts of new media was prankster Ian Murphy, posing as billionaire conservative-activist David Koch, phoning a solicitous Walker to discuss the protests. The 10-minute call (the YouTube version has been cued up more than 800,000 times) prompted a liberal firestorm and wounded Walker politically. Shah says that new-media partisans of all stripes love to slice and dice unrehearsed comments like these to damage the other side.

“That’s the intent of the people collecting it,” he says. “They go in with the intent to embarrass.” As for the Walker call, Shad says, “You can pick out the embarrassing quotes, but the overall tone of the conversation — the governor managed it pretty well.”

Over at Isthmus, the Madison weekly I used to edit, the paper broke new ground by aggregating 140-character Twitter comments that became the heartbeat of the protests. The paper deployed CoverItLive blogging software to create a day-long stream of comments from activists, other media and its own reporters — up to two or three posts a minute — to provide live continuous coverage of the protests.

“People wanted to know what was going on every minute,” says Jason Joyce, the paper’s digital media director.

Joyce wasn’t exaggerating. Public interest in in the Walker budget repair bill —rife with national implications because of the dagger it aimed to the heart of the unions — was extraordinarily high. Reporters and editors had never seen anything like it.

“More than anything, the immediacy of the Internet and the crushing pace of this story fit each other really well,” says Jason Stein, a Capitol reporter with theMilwaukee Journal Sentinel. “This wasn’t a day-by-day, or even hour-by-hour story; many times it was a minute-by-minute story in which the public wanted to know what was going on in each of those minutes.”

Little WTDY, a Madison AM radio station, even web-streamed the audio of a crucial court hearing before Circuit Judge Maryann Sumi, expecting a few dozen listeners at best, according to reporter Dusty Weis. Well over 400 people clicked on, he notes, and they flooded the station with calls when a glitch briefly interrupted the feed.

The Journal Sentinel, with the state’s biggest and best newsroom, augmented its two-person Capitol bureau with up to four or five other reporters and did, as Stein puts it, “saturation posting” at the paper’s website, updating stories all through the day.

At one point, he says, he worked 22 straight hours.

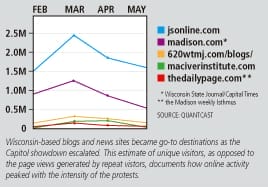

Local news editor Gary Krentz says a simple change on the paper’s website made it easier for Facebook and Twitter users to share Journal Sentinel stories. “That had an enormous impact on page views,” he says.

Viewership rose to big-storm levels, to even Packers-win-the-Super- Bowl levels. On the day when 14 Democratic senators fled the state to block to anti-union vote, page views at JSOnline hit 3.9 million, Krentz says. The day after the furiously contested state Supreme Court race ended in a seeming toss-up between incumbent David Prosser and little-known challenger Joanne Kloppenburg, the paper’s website peaked with a stunning 4.2 million page views, including almost 400,000 hits in a single hour.

“Interest was insatiable,” says Stein, who says he regularly fielded interview requests from national media outlets wanting to know what was happening in Wisconsin.

For an old-media creature like a newspaper, rising to the top of the online world was a rare moment of vindication of its work. Still, there’s little sign that success online did much to offset the hemorrhaging of revenue that has sent the newspaper into a tailspin. Financial statements for Journal Communications Inc. show that only about 7% of the daily paper’s revenue came from its interactive media in the first quarter of 2011.

The revolution in media is undeniable. In an influential essay published two and a half years ago, media critic Clay Shirky saw history in the making. He compared the explosive rise of new media — it has blown up the quasi-monopolistic economic model that sustained papers like the Journal Sentinel — to the upheaval unleashed by the introduction of movable type in the 15th century.

As Shirky recounts, Gutenberg’s supremely disruptive technology broke the Catholic Church’s monopoly on books. The Bible was quickly translated into contemporary languages. Literacy spread. Erotica appeared. The writings of Copernicus and Martin Luther rocked the established powers. Governments shuddered and toppled. All this came from Gutenberg democratizing the printed word.

Now we have the smart phones, social media and the worldwide web creating their own sweeping changes. If Shirky has it right, only in retrospect will true turning points be identified, a narrative constructed and sense be made out of the ever-morphing media revolution. Wisconsin may even get a featured chapter in its history.

Althouse, in an email discussing the protest videos posted by she and her husband, gets to the truth of the situation when she says “we were inventing and discovering as we went along.”

Althouse describes new media as an “emerging process” — something that MacIver’s Fraley would agree with. “You have to be flexible and play to your strengths,” he says of his group’s new-media strategy. “We don’t get to choose how people get their information.”

In breath-taking quick fashion, Fraley says the digital revolution began with dotcom publishing, shifted to the searched-based Web and then to email. “Now it’s social media — Facebook and Twitter. Two years from now it could be something that’s not even invented yet.”

That politics — or more precisely, the mechanics of politics — will betransformed by new media is obvious to everyone. Not so obvious is if politics itself will be changed.

“Social media won’t turn people out for something they’re not passionate about,” says Katy Culver, a faculty associate at the UW-Madison journalism school. “Twitter and Facebook are good about telling people about the ‘where’ and the ‘when,’ but the ‘why’ ‘is something is something they have to feel in their own mind.”

Her colleague Shah makes much the same point. Thanks to social media, “we’re more mobilized around the issues that concern us,” he says. “Participation seems to be spurred whether it’s voting or turning out for protests.”

But he and Culver differ sharply on the political impact of social media. Shah basically sees it as reinforcing the same polarized thinking that has gripped the country in recent years. Liberals and conservatives have stoked their ideological fires by following websites, listening to talk radio and watching cable news that reinforces their existing opinions. “Our social networks tend to be ideologically homogenous as well,” he says.

Culver says that both research and anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. Our social networks are more diverse, she says, because we fashion them not from our ideological fellow travelers, but from our family members, work colleagues and schoolmates.

But even if Culver is right about the diversity of our “friends,” the present tone of our politics would seemingly back up Shah’s interpretation. The rise of social media has had little impact on the polarization of American politics. No middle-of- the-road, “third way” movement has been texted into public consciousness.

If anything, the new technology has been deployed in the revival of a grand old creedal fight. Surging conservatives are rolling back 50 years of liberal Democratic programs in Wisconsin and even challenging the Progressive and New Deal shibboleths of earlier generations. New media has been conspicuously agnostic in this war, equally available to the left and right.

The irony is that the epochal rise of digital media may wind up triggering Gutenberg-like changes in our culture and economy, in the transmission and creation of news, and in the very nature of our intimate communications. But in the substance of our politics — well, not so much. At least for now.

Marc Eisen is managing editor of Wisconsin Interest

Photos by Eloisa Callender