Lake Wobegon has nothing on the UW-Madison School of Education. All of the children in Garrison Keillor’s fictional Minnesota town are “above average.” Well, in the School of Education they’re all A students.

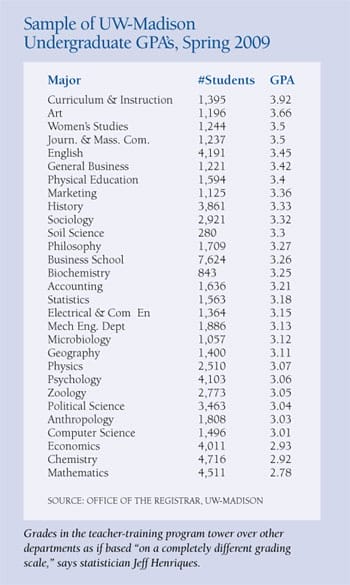

The 1,400 or so kids in the teacher-training department soared to a dizzying 3.91 grade point average on a four-point scale in the spring 2009 semester.

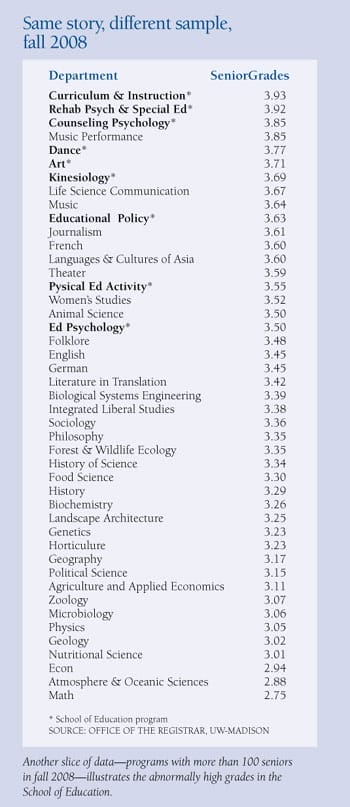

This was par for the course, so to speak. The eight departments in Education (see below) had an aggregate 3.69 grade point average, next to Pharmacy the highest among the UW’s schools. Scrolling through the Registrar’s online grade records is a discombobulating experience, if you hold to an old-school belief that average kids get C’s and only the really high performers score A’s.

Much like a modern-day middle school honors assembly, everybody’s a winner at the UW School of Education. In its Department of Curriculum and Instruction (that’s the teacher-training program), 96% of the undergraduates who received letter grades collected A’s and a handful of A/B’s. No fluke, another survey taken 12 years ago found almost exactly the same percentage.

A host of questions are prompted by the appearance of such brilliance. Can all these apprentice teachers really be that smart? Is there no difference in their abilities? Why do the grades of education majors far outstrip the grades of students in the physical sciences and mathematics? (Take a look at the chart below.)

More important, what is the real-world educational consequence of this training? Once they’re in classrooms of their own, do UW graduates grade their own students with a similar broad brush of excellence?

But I fret too much. Everything is fine. That’s what I was told by the leaders of the UW-Madison School of Education. Let’s hear their story.

Simply put, UW-Madison’s program is one of the best in the nation. It’s ranked #7 in the U.S. News and World Report annual assay of the nation’s more than 200 education schools. The all-important Curriculum and Instruction department is, in fact, #1 in the nation for teacher training, according to the magazine’s survey of education deans.

Prof. Gloria Ladson-Billings, who chairs Curriculum and Instruction, says educators in other states marvel over the quality of UW-Madison’s graduates. “They love hiring our students,” she says. “Our graduates stand out from the rest.”

The complaint that her school is soft and squishy on grades is quickly dismissed. Ladson-Billings doesn’t bat an eye as she tells me the grades are so good because the students are so smart.

Here’s the context to keep in mind, she tells me: It’s darn hard to get into UW-Madison in the first place, and then the School of Education weeds out applicants when they apply for admission as juniors.

“We’re highly selective,” says Ladson-Billings. “These students have already proven themselves and established a certain grade point. It’s a competitive process, and it pushes the low performers away.”

If I’m still harboring doubts, Ladson-Billings offers a presumed clincher: “We have people who love this field. They choose it. They’ve stayed the course. They’re probably going to be successful.”

Jeff Hamm, an associate dean for academic services, makes the same case. “Honestly, we’re trying to pick the best of the best. We’re not taking average students. They don’t get C’s,” he says.

I received a slightly different and perhaps more revealing explanation from graduate student Doug Larkin, who says grades aren’t really important because the School of Education focuses on student learning.

“We model for our students what we expect them to do with their students-to keep working with them until they produce high-quality work.”

He adds: “It’s our philosophy. Education is not a sieve. We don’t exist to sort students into grade categories. We work with them until they get it.”

Larkin put in 10 years as a high school physics teacher in Trenton, N.J., before heading to graduate school to prepare for teaching education at the professorial level. Why the career shift? “I hit the limit of change I could effect in the classroom,” he says. “I realized some of the problems we faced weren’t necessarily solvable by an individual teacher.”

Larkin talks about wanting to create “more positive social change” and how the achievement gap between white students and kids in poverty (“the education debt,” as he prefers to call it) is “a cumulative thing related to housing patterns, employment and social services.”

He makes no mention of what role bad teachers, dysfunctional families, or low expectations have in the performance of kids reared in poverty.

Politically, educators these days can be put in roughly two camps-“liberal traditionalists who rally around teachers unions and education schools” and “free-market reformers who believe [in] competition, choice and incentives,” as New Yorker writer Carlo Rotella recently put it.

There’s no doubt about the UW School of Education’s orientation. Its students are “very committed to social progress and to social change,” says Hamm. But the skeptic in me keeps wondering: What about educational excellence?

That question is the bone that progressive educators can never quite swallow and make disappear.

Harvey Mansfield, a professor of government at Harvard, complains that compressing all grades at the top makes “it difficult to discriminate the best from the very good, the very good from the good, and the good from the mediocre.”

He writes: “Surely, a teacher wants to mark the few best students with a grade that distinguished them from all the rest in the top quarter, but at Harvard that’s not possible.”

Indeed, concerns about grade inflation are hardly unique to UW-Madison. This is a topic that periodically roils the academic waters from coast to coast, often with an outright political subtext.

On the left, there is Alfie Kohn, the indefatigable defender of progressive public education. When he’s not denouncing high school honors classes, homework, testing, letter grades, award ceremonies and academic competitions, not to mention keeping score in high school sporting contests, he goes on at great length to deny that grade inflation even exists (which infuriates the statisticians who’ve studied the phenomenon). Kohn, who’s capable of marshaling great outrage when he writes about these topics, denounces any talk of grade inflation as a “dangerous” conservative plot.

Stuart Rojstaczer, who’s put together the most comprehensive database of grade trends at American colleges and universities, harrumphs that Kohn’s claims “ignore data and are without merit.”

Rojstaczer writes that “significant grade inflation is present virtually everywhere, and its rate of change in terms of GPA shift is about the same everywhere.” (He found that the average GPA rose from 2.93 in the 1991-92 academic year to 3.11 by 2006-07. Other data can be cited as well, but doing so would make your eyes roll back.)

When Rojstaczer and I exchanged emails, he told me that his research shows that “education schools seem to have the most lax standards of any schools in the country.”

Caitlyn O’Mara, 22, has the passion and enthusiasm you want in an apprentice teacher. The fifth-year senior sees the pros and cons of her training at the UW-Madison School of Education.

She loves the fact that she’s studied with the same cohort of 25 education students since her admittance to the teaching program. She also likes that every semester the program has her in an actual K-12 classroom. And she praises the support the School of Education offers her. In other words, the school does some things very well.

“But I don’t think we’re necessarily held accountable to the school’s high standards as much as we should be,” she says. “And I do think there are people who slide by, who may not go to class. I’m in a group that does not have a whole lot of that, but I can’t imagine it doesn’t happen.”

Earlier, O’Mara pointed to herself: “I know I’ve turned in papers that weren’t maybe as good as the person next to me’s, but I’ve gotten an A. Does that happen everywhere? Yes. Does it happen in the School of Education? Yes.”

For Lee Hansen, a retired economics professor at UW-Madison, that’s the fundamental problem with grade inflation: “If people are not stretched, they will not develop their talent to the fullest extent.”

And, hey, isn’t that the essential mission of education: to help kids realize the intellectual potential locked away in their hormone-crazed, easily distracted noggins?

Statistician Jeff Henriques argues that serious grading is indispensable to both teacher and student success in the classroom. He teaches introductory psychology and uses grades as a diagnostic tool.

“Grades are an indicator of what different students have learned,” he says. “I also use them as information on how good a job I’m doing as a teacher and to evaluate the changes I introduce into my curriculum.”

Only after I reviewed my notes and looked at their cool pixels on the screen did I realize how utterly commonplace Henriques’ observation was: Grades are a measure, umm, of success? Only in an era when just about everyone and their dog get an A would such a truism stand out as exceptional.

But it does.

Like Hansen, Henriques feels students respond to the challenge of tough grading. When he’s made it easier for students-for instance, by posting his lecture notes and slides online-he found they tested more poorly than when he peppered them with chapter quizzes.

“More and more, I’m coming to believe that we help our students the most if we really challenge them, if we push them to work,” says Henriques.

As for the School of Education’s approach to grading, Henriques pauses and politely offers: “I would say it’s not really helpful in distinguishing between students or in evaluating the curriculum if they try to make any changes.”

Earlier, when I emailed Henriques my interests in the story, he put on his statistician’s hat and compared the grades of senior education students to the grades of seniors in other programs-and found the bunching of the Ed School scores so extreme that they appeared “drawn from a different distribution from the rest of the university.”

Put another way, the ubiquitous A in Education doesn’t compare to an A in Chemistry or Mathematics or most other disciplines.

Another telltale discrepancy emerged in a comparison of ACT scores to the grades of UW System graduates over a three-year period. Not unexpectedly, Ed School grads had a higher GPA (3.6) than other graduates (3.3) at UW-Madison. Their aggregate ACT score, however, was lower compared to other graduates, 26.5 to 27.6. (System-wide, among the 13 UW campuses offering teacher training, the ACT spread between education and other graduates was even bigger.)

The higher grades/lower ACT scores of education students is one more reason to wonder if they are as smart as their grade point averages seemingly demonstrate or as their professors believe.

Grade inflation is the elephant in the room that academia would happily ignore. I was surprised at how many otherwise garrulous UW-Madison professors bit their tongues and faded into the woodwork when I asked them about it.

I also was blown off by a national educational group that agitates for improved teaching as part of a reformist agenda. And I came up empty-handed when I sought to interview education experts at Teachers College in Columbia University. The press person told me that the “two people [who] would make the most sense on this are not willing to say anything publicly about a competing institution.”

The reason for the conspicuous silence is probably this: Nothing is going to change.

Reality is that grade inflation is a logical product of university dynamics, as Valen Johnson, a biostatistician at the University of Texas and author of Grade Inflation: A Crisis in College Education, told me.

“Reforming the system isn’t in anyone’s interest,” he explains. “The faculty doesn’t want to assign lower grades because they’ll get more complaints, and their course evaluations will get lower, and fewer students will enroll in their classes.”

The bottom line is that tough-grading profs run the risk of being penalized in tenure and salary decisions, he says. Students, of course, “don’t want grade distributions to go down because it hurts their chances of landing a good job or getting into graduate schools.” As for administrators, “they certainly don’t want to deal with grade inflation, he says, “because if they do then both the faculty and the students get upset.”

The stalemated discussion usually plays out once a decade or so at UW-Madison. Concerns about grade inflation well up, op-eds are written, committees are formed, conferences are held, and nothing happens.

Johnson learned this lesson firsthand at Duke University in the 1990s when he spearheaded an unsuccessful effort to recalibrate student grade point averages to reflect the different grading policies of professors and departments. He did a book’s worth of research on grading patterns and found “incontrovertible evidence” that grading practices differ by academic field.

As you might guess, the humanities were the most lenient, and the natural sciences, math and economics the toughest in grading.

Johnson sees “deep philosophical divisions” producing the standoff. Traditionalists see grades as maintaining academic standards and providing a summary of student achievement. Liberals think praise and encouragement (and awarding good grades) will motivate students to do better. Hip postmodern professors, meanwhile, see grades as culturally biased and fatally tainted by false objectivity.

Out of this philosophical muddle emerges Curriculum and Instruction’s Lake Wobegonish world of A’s for almost everyone. When I asked Johnson if he sees things turning around, he dryly observed: “It seems at UW-Madison that grade inflation will now stop because grades really can’t go any higher.”

How this plays out with students, of course, is the real question. For all the A’s that are handed out in the School of Education, Caitlyn O’Mara isn’t sure that things are as topnotch as the classroom GPA would seemingly indicate.

There’s a curious refusal among students to confront one another, as if one opinion is just as good as another, she says. “We can’t have those honest discussions about inclusion and race, because there is a level of political correctness.”

She cites as an example: “Nobody wants to talk about why [K-12] grades can be predicted by socioeconomic status and racial status. We don’t have an open dialogue about that.”

Still, O’Mara praises what she says are “the fantastic ideas” she’s taught on incorporating social justice into her teaching. “But you walk into the classroom and you get kind of a reality check,” she admits. There may not be the time, resources or institutional support to pursue any of it.

“I go to my methods courses early in the week, then I teach in my practicum classes later in the week and I get the wind knocked out of me,” she says matter-of-factly. “What I read about is not what I experienced. I wasn’t prepared for the kind of challenges I meet in the classroom.”

Marc Eisen is a reporter and editor in Madison.

The UW-Madison

School of Education in brief

Dean: Julie Underwood.

Enrollment: 2,987, including 1,875 undergraduates (2008).

Staff: 637, including 139 faculty and 156 graduate students (2007).

Degrees granted: 561 bachelor’s; 242 master’s; 55 Ph.D.’s (2007-08).

Departments: Curriculum and Instruction; Counseling Psychology; Art; Educational Leadership & Policy Analysis; Educational Policy Studies; Educational Psychology; Kinesiology (includes physical education and occupational therapy); and Rehabilitation Psychology & Special Education. Dance is a separate program.

Research centers: Wisconsin Center for Educational Research; Minority Student Achievement Network; Center on Education and Work; and others.

Alumni: 44,450.