The Joseph Project addresses regional employment challenges with a free-market approach

Christopher Lane’s employment prospects were bleak. In 2015, the 45-year-old former felon lost a Milwaukee city government job when he was arrested on a charge that later was dropped. With a 20-year prison term for armed robbery on his record, Lane found his opportunities limited to temp work and side jobs.

Then a chance encounter rekindled his hope.

“I was going to see my probation officer when I ran into an old friend,” Lane says. That friend, Willie McShan, told him about the Joseph Project, an unusual partnership between an urban Milwaukee church, a handful of Sheboygan County manufacturers and a U.S. senator’s office.

The career placement project had helped McShan, 53, land a full-time job with Nemak, an automotive components manufacturer in Sheboygan. The position paid nearly $15 an hour, much more than he had been making at temp jobs. Better yet, it provided stability, benefits and opportunities for overtime.

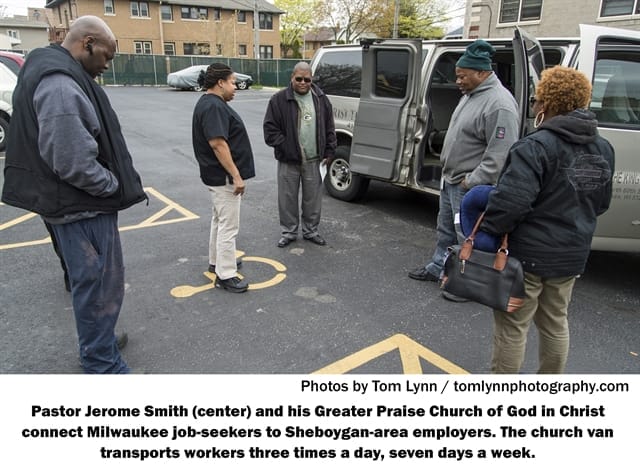

McShan connected Lane with Pastor Jerome Smith of the Greater Praise Church of God in Christ, at 5422 W. Center St. in Milwaukee. The church is the fulcrum in the partnership between employment-seeking Milwaukeeans and employee-hungry businesses in the Sheboygan area.

Pastor Smith starts by conducting a vigorous background check. Applicants who pass then must complete a week of preparatory workshops. Greater Praise partners with other area churches to offer job-seekers instruction on financial fitness, conflict resolution, spiritual well-being and stress management. Those who complete the coursework are guaranteed an interview with one of the participating businesses.

Although the course participation meant a week without pay, Lane decided it was too good an opportunity to pass up. “My heart said, ‘Try the workshop.’ ”

“It was very positive,” he says. “They keyed in on job interviews; they keyed in on good attitude.” The training was humbling, he adds, “because there were people whose circumstances were even worse than mine.”

The church plays another critical role in this intercommunity partnership. Three times a day, seven days a week, the church’s 13-year-old, 15-passenger van delivers employees from the Greater Praise parking lot to the Sheboygan manufacturing facilities of Nemak, Kohler Co., Polyfab Corp., Johnsonville Sausage and Pace Industries (in Grafton). Riders pay $6 round trip.

After completing the workshops, Lane interviewed with Johnsonville. He was hired in March as a sanitation technician and earns just over $16 an hour, plus a $1 hourly premium for working third shift. He also puts in a lot of overtime.

“It’s definitely a good experience,” he says. “The company looks out for their employees.”

Tackling two problems at once

More than 40 Milwaukee residents are working full time for Sheboygan-area companies through the Joseph Project. The first cohort of employees started work in October 2015. Dozens more are applying as word spreads.

The concept began to germinate last year as Orlando Owens, the southeast regional director for U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), wrestled with two different — and seemingly intractable — regional problems.

One was the high unemployment rate of African-Americans in Milwaukee. In 2014, just over 51% of working-age African American males in Milwaukee (ages 16-64) were employed, according to Marc Levine, professor of history, economic development and urban studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Of white males in that age group, 80% were employed.

The other challenge was a recurring refrain from outstate Wisconsin manufacturers: We can’t find enough people for our growing workforce. The problem is particularly acute in Sheboygan County.

The county is “growing economically faster than any other county in the state,” says Dane Checolinski, director of the Sheboygan County Economic Development Corp. (SCEDC). There are currently 3,300 unfilled jobs in the county, he says.

Owens recalls talking with an SCEDC representative about the human capital shortage when a light bulb went on. “I said, ‘Listen, man, I’m from Milwaukee. I have adults right now who are looking for work. So, if you’ve got all these jobs and we’ve got all the people, let’s make something happen.’

“So, they came down, did a presentation right here at the church with Pastor Smith and maybe three other pastors and more members of the faith community. After that, we went up there and took a tour of maybe three companies. From there, it just exploded.”

Pastor Smith sees the project as a common-sense solution. “Sheboygan had a problem,” he says. “They had more jobs than they had people. Milwaukee had a problem. They got more people than they got jobs. So, let’s fix both problems at once.”

Employers and workers both win

Anne Smith, corporate public relations manager at Kohler Co., describes the partnership as a “win-win.” Kohler so far has hired 13 employees through the Joseph Project, she says.

“The associates working at Kohler are doing well, and we are expanding the opportunity to additional area residents who are interested in employment with Kohler,” the company said in a statement.

Lakeesha Lofton is one of those employees. Lofton, 37, was looking for work when her stepfather told her about the project. He had gone through the workshops and landed a job at Kohler. Lofton followed his lead. She is now working 58 hours a week packing materials.

“It’s an opportunity to get your life together,” she says.

Rick Gill, president of Polyfab, says, “I’m just glad that people have taken this initiative. This would be difficult to do by ourselves.”

The SCEDC is so happy with the results that it is donating two vans to the Greater Praise Church, according to Checolinski. He notes that no company has dropped out of the project and that the employee retention rate is higher than when the companies did their own recruiting.

“I really, really love this program,” he says.

Checolinski offers three reasons the Joseph Project has been successful when other employment initiatives have failed: grass-roots recruitment, the project’s vetting and training process, and the incentive of a guaranteed interview for those who complete the workshops.

Owens agrees: “It’s an all-hands-on-deck approach that benefits everyone. We know that our individuals may have some bumps and bruises, so the best thing we can do is try to have them as prepared as possible.”

This relational, empowering, market-based approach is the key to effective engagement with people in need, says Bob Woodson, president of the Center for Neighborhood Enterprise, based in Washington, D.C. The Joseph Project derives its name from a 1998 book written by Woodson, “The Triumphs of Joseph: How Today’s Community Healers Are Reviving Our Streets And Neighborhoods.”

The Joseph Project “is resurrecting common sense,” says Woodson. It creates “an expectation that people will be agents of their own uplift.”

Differs from government models

Woodson cites several ingredients that distinguish the Joseph Project from government models:

- The leaders are in the same community as the people they’re serving.

- The leaders recognize that people aren’t seeking a safety net but an avenue out of poverty.

- The goal is not to get people comfortable with poverty but to get them out of poverty.

- The project is motivated by love. “This pastor’s love comes through,” Woodson says of Smith. “You can serve people without loving them, but you can’t love them without serving them.”

In an era when discourse on poverty and welfare issues often devolves into partisan rancor, the Joseph Project provides a model that transcends racial, regional, sectarian and political divides — all while providing opportunity and transforming lives.

“This model is trans-political, trans-ideological,” says Woodson. “The best ones are. That’s what the country is thirsting for.”

The initiative runs entirely on individual donations; it doesn’t accept state or federal money. The cost for paying drivers and maintaining the van averages about $6,000 a month, according to Pastor Smith. Contributions come from “the general public that sees the value in what we’re doing,” he says.

Lane is spreading the word to other job-seekers. “I say, ‘This is an opportunity you’re not going to see all the time. They don’t baby-sit you; they don’t hold your hand. They put it out for you to grab.’ The whole program is geared to let us take charge.

“This program is like a second birth, like a second hope,” he adds. “A lot of times you get stuck in dead-end jobs. This is a second chance.”

Michael Jahr is co-founder of the Better Yes Network, which connects and strengthens nonprofits that focus on personal and community restoration. He has written on policy issues for The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard and numerous other publications.