Stats raise questions about gridlock and political posturing

Wisconsin lawmakers in both the Senate and Assembly are introducing record numbers of bills — well over 50% more than 10 or 20 years ago — despite dramatically decreased chances of ever seeing them made into law.

In both of the two most recent legislative sessions, legislators introduced just over 2,300 bills and saw less than 12% enacted.

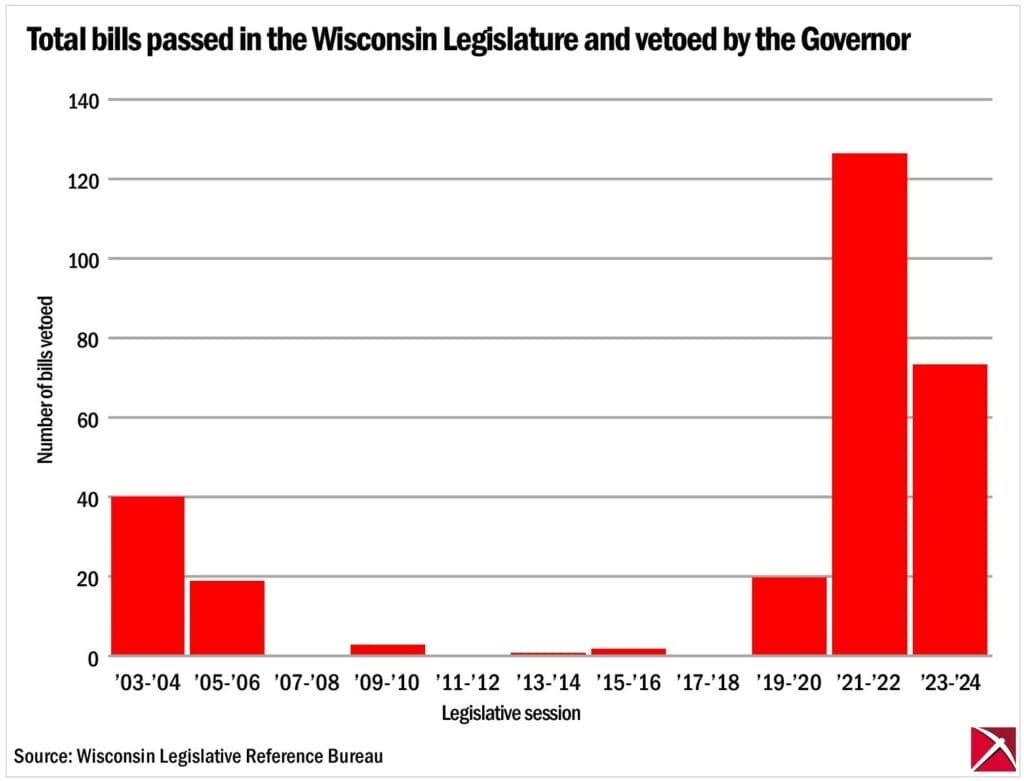

Gov. Tony Evers has vetoed more legislation than any other governor in at least two decades, almost 200 bills in total in the last two sessions.

But that is only a small part of the story. Legislators authored over 900 more bills in the just-ended 2023-24 session than in the 2011-12 session, for instance, and over 800 more than in the 2003-04 session. Roughly the same amount — 268 in the most recent session and between 243 and 289 in the earlier sessions — became law.

Conservatives who believe in smaller government often see minimal new legislation as a victory. But the high numbers of bills introduced and vetoed raise questions about legislative wheel-spinning, gridlock and political motivation.

For people who have made a living paying close attention to how these things work, the new gridlock is different. In his 21 years as a rules committee clerk in the Assembly, Bob Karius says he saw elected officials in even the most fractured state governments working with the other party to get things done.

“Given the way things are, the media and Governor Evers love gridlock,” Karius says. “He has the most anti-bipartisan staff and administration in the history of the state. They’ve almost chosen gridlock. That’s their game.”

Prior to Evers taking office in 2019, the Legislature could expect that 20% to 25% of the bills introduced (this includes “companion bills,” identical versions of one chamber’s bills introduced in the other chamber) would be enacted in any given session. Those numbers plummeted to 9.4%, 11.6% and 11.5% in the last three sessions respectively, according to numbers from the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau.

“I think there is a story of increasing polarization and the expansion of executive power,” Ryan Owens, a professor of American politics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says. “Everything is dysfunctional these days.”

Why then, if the chances for enactment are getting slimmer by the session, are lawmakers so bill-happy?

Many of the traditional calculations are still in play for lawmakers, Karius says. What party does the governor belong to? What is the makeup and the size of the majorities in the Assembly and Senate? Will special elections change that makeup, and what of the natural turnover from election to election? And, Karius says, it’s even a matter of something as elementary as whether the governor, the speaker of the Assembly and the Senate majority leader, regardless of their parties, can get along.

There is a subtler effect of gridlock, and it has more to do with the modern nature of politics, Owens and Karius say. Legislators in both parties who know their bills are going to be blocked have other incentives to force their political opponents, especially the governor or high-ranking members of the Assembly or Senate, to take positions on bills that send a clear message to voters. Introducing bills not only sends messages to constituents about a lawmaker’s positions on issues, it lets them know their representatives are actually doing something when they are in Madison.

“If you are in the majority and your majority is so big, how do you stand out?” Karius says. “There is a very real sense sometimes that if you aren’t passing bills, you’re not doing very well.”

In May 2007, the non-profit WisconsinEye Public Affairs Network began broadcasting the daily goings-on of legislative sessions. It might only be coincidental that the total number of bills introduced jumped by 9%, from 1,579 that session to 1,720 the following session, but Karius says the new medium’s impact in the Capitol building was immediate.

“You had lawmakers on the floor speech-making, wasting hours on the floor for the, like, 100 people watching it,” Karius says. “We had to tell them to cut it out.”

Now with the explosion of social media, lawmakers have further incentive to file bills to send messages and curry attention, Owens says.

| Session | Total bills introduced | Total enacted | Percentage enacted | Total vetoes |

| 2023-24 | 2,331 | 268 | 11.50% | 73 |

| 2021-22 | 2,307 | 267 | 11.57% | 126 |

| 2019-20 | 1,988 | 186 | 9.36% | 20 |

| 2017-18 | 1,999 | 367 | 18.36% | 0 |

| 2015-16 | 1,830 | 392 | 21.42% | 2 |

| 2013-14 | 1,648 | 383 | 23.24% | 1 |

| 2011-12 | 1,399 | 289 | 20.66% | 0 |

| 2009-10 | 1,720 | 403 | 23.43% | 3 |

| 2007-08 | 1,579 | 239 | 15.14% | 0 |

| 2005-06 | 1,967 | 489 | 24.86% | 19 |

| 2003-04 | 1,477 | 243 | 16.45% | 40 |

The Badger Institute reviewed statistics for both regular and special sessions provided by the Legislative Reference Bureau and clerks for both chambers for legislative sessions going back 20 years. The period includes split government on either end and eight years, from 2011-2018, when Republicans occupied the governor’s office and enjoyed majorities in the Assembly and Senate.

There was a time that the Assembly outran the Senate in the sheer numbers of bills filed. In 2003, Assembly members introduced 998 bills, more than twice the 479 introduced by Senate members. By 2021, just 91 bills separated the Assembly’s 1,199 and the Senate’s 1,108.

“You’ve got Assembly members being elected to the Senate and taking that mindset about the bills with them,” Owens says. “By 2012 the Senate and Assembly numbers start to match.”

The ascension of progressive Janet Protasiewicz to the state Supreme Court and the resulting liberal court majority has spurred an agreement between Evers and Republican leadership on new legislative district maps.

Karius says the Senate majority might shift to the Democrats in the near future. The Assembly majority could be Democrat in a couple of sessions. And with a volcanic presidential election this November, who knows which way voters will go in the 2026 gubernatorial race?

Regardless of the reconfiguration, Owens says the political polarization in the state isn’t going anywhere. Whether in a majority or minority, lawmakers have learned the lessons about legislation.

“So long as you have divided government, the enactment numbers are going to be low,” Owens says. “But with the pressure to be re-elected and the demands of social media, I think the introduction numbers are only going to increase.”

Mark Lisheron is the Managing Editor of the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields