Universities can cash in on faculty brainpower and inventions

The University of Wisconsin system earlier this month recommended downsizing its two-year branch campuses. That same week, Concordia University announced it is exploring downsizing or shutting down its Ann Arbor campus after recent downsizing at its Mequon campus. This comes after the closing of Cardinal Stritch University last year and a recent announcement by Marquette University of a $31 million budget cut by 2031.

The list goes on.

Alverno College just announced plans to cut 37 faculty and staff, while Northland College, Marian College, and St. Norbert have all faced financial challenges.

There is a crisis in higher education, brought about by costs and demographics. There are, however, ways for colleges to adapt, overcome and improve — if they’re willing to take advantage of technology and the brainpower already in-house. Perhaps it is time to innovate.

Fewer students

The “demographic cliff” contributing to the problem was foreshadowed by Nathan Grawe at Carleton College in his book “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education.” We can expect a decline in the number of college-aged students of as much as 15% in the coming five to 10 years.

More colleges and universities will need to close or downsize.

Increasing cost and questionable value

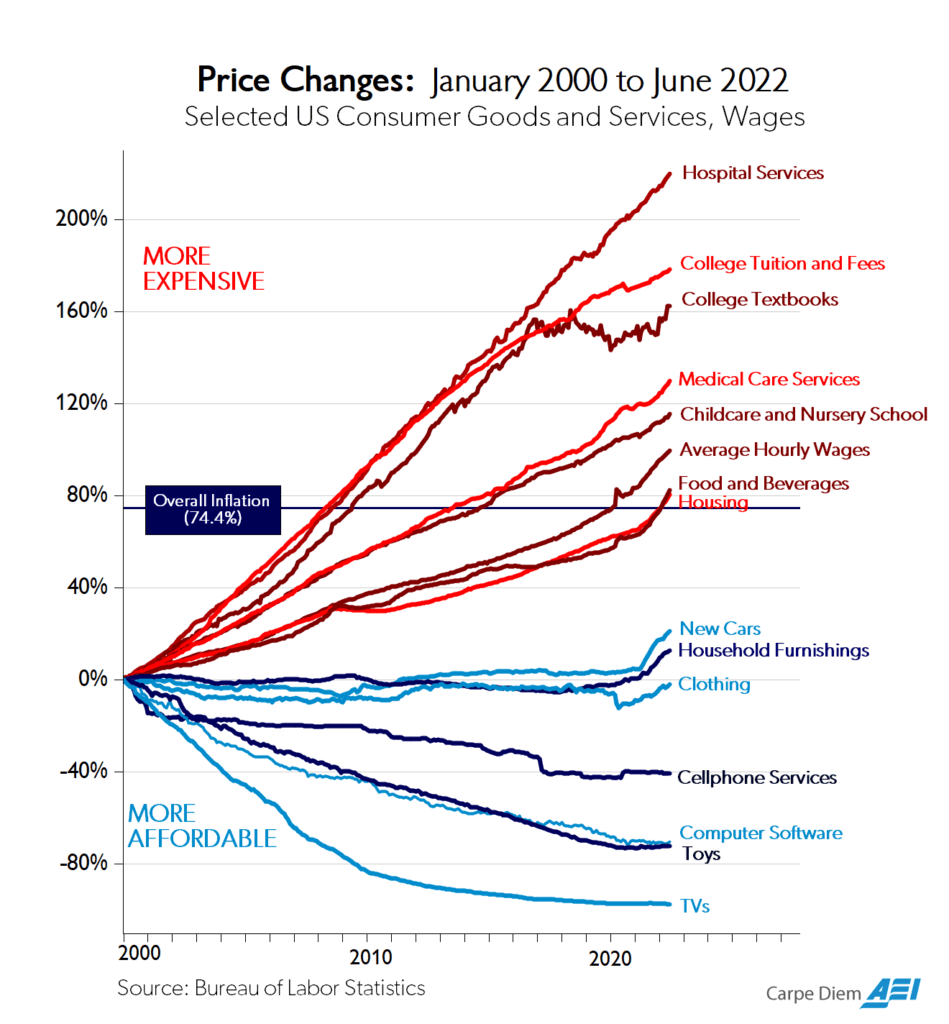

There has been a continuous increase in the cost of higher education since at least 1998, far outpacing inflation and matched only by the rising cost of healthcare (Fig. 1). Richard Vedder has argued that at least one contributing factor is the federal government’s increase in aid (especially Pell grants), which increases the demand for college and leads to both higher debt for students and higher tuition.

Of course, the other reason tuition is so expensive is that universities have spent too much on physical and administrative infrastructure that students have been enticed into paying for with a lifetime of long-term debt they can hardly grasp at a young age. We can’t eliminate or diminish the campus experience. The social and human experience of college is vital. But do we really need so many nice buildings and amenities for students who are looking primarily for an education and not for a country club experience they will be paying off for the rest of their lives?

Fig. 1

Many potential students are questioning the value of a four-year or graduate degree. And one report estimates that 45% of companies plan to eliminate the requirement for bachelor’s degrees for some positions. But the data do confirm that a college education is worth the investment. Salaries of college graduates are on average 75% higher than those of high school graduates.

Time to innovate and find creative solutions

So how do colleges and universities innovate?

Some universities already capitalize on the brainpower within their ivory towers to commercialize inventions. WARF at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has reaped hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties from Warfarin and from vitamin D and related drugs resulting from the research and innovation of faculty. The cancer drug cisplatin was discovered by faculty at Michigan State University, and it resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars to supplement tuition and philanthropy. Northwestern University has benefited from Richard Silverman’s research that produced the drug Lyrica.

Why not nurture and expand this alternative revenue source, especially for mid-sized universities that can’t afford the large technology transfer infrastructure of larger research-intensive universities?

That is the aim of CU Ventures, affiliated with Concordia University, and which I lead. CU Ventures has assembled an angel investor group comprising alumni and friends of the university who listen to pitches from startups connected to or affiliated with the university or its partners. They have invested more than $1 million in the last two years in eight spinout companies, with CU Ventures having equity or carried interest in all. These investments serve the sole purpose of supporting the educational mission of the university, with revenue going to scholarships and grants. Of course, like most angel and venture capital investments, the timeline for returns is long, five to 10 years, so this is an investment in the future.

The model is innovative and is an enticing potential third source of revenue for universities, tapping into the brainpower of faculty in a collaborative and mutually beneficial way, helping them take research to market while giving students applied learning experiences.

This model has been so successful (albeit still in early stages) that we are now looking to franchise it, forming a nonprofit called University Venture Affiliates (UVA) with Walsh College in Michigan. UVA aims to help universities across the Midwest form angel investor groups to invest in and support commercialization of the innovation coming from their faculty, staff, students and partners. This is a disruptive innovation in higher education that expands the technology transfer model of the larger universities and leverages free market principles.

Other types of innovation

Universities can also become more efficient in how they provide an education.

Some fear a loss of jobs from AI, but that should be no truer a threat than going from the abacus to the slide rule to computers to cloud computing, or from assembly-line manufacturing to robotics. Current thinking is that AI won’t replace teachers; it will leverage them, help them automate routine tasks, let them focus on higher-value interaction with students. AI teacher assistants could answer routine questions and handle routine tasks, allowing the teacher more time to address more complex questions, teach critical thinking as well as soft skills like communication.

This is happening now and is even being deployed via a spinout company from Concordia University, csiSIM.

In summary

The demographic cliff and the out-of-control increase in the cost of a college degree has led to decreased enrollment, decreased revenue and even closures. Universities that innovate will win the market competition for students and dollars.

The Ivy League and larger universities with big endowments, as well as large public universities, will survive as long as they make adjustments, but everyone else is subject to market forces and could be on the chopping block if they don’t adapt.

Daniel Sem, Ph.D., MBA, JD, is a visiting fellow at the Badger Institute.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields