Even failed and troubled ones like the Job Corps training centers are nearly impossible to shut down

Here’s a bizarre tag team for you: liberal Democrat Tammy Baldwin, the Madison darling of the left wing, teaming up with uber-conservative North Woods Trump supporter Sean Duffy to take down an administration plan to ax a rural job training program.

U.S. Sen. Baldwin and then-Congressman Duffy were the state’s political odd couple. Poles apart ideologically, the two found common ground in the one area on which all politicians seem to close ranks: federally funded jobs for voters back home.On paper, the Trump proposal in May was a no-brainer: Close nine low-performing Job Corps centers operated by the U.S. Agriculture Department — including one in northeastern Wisconsin — and transfer 16 other centers to the U.S. Labor Department, a better fit for a job-training agency.

The 25 rural centers targeted were Civilian Conservation Centers (CCC), a subset of the Job Corps run by the Ag Department’s Forest Service. The Labor Department operates the remainder of the 123 Job Corps centers across the country.

Part of sweeping changes in the Trump administration’s 2019 budget, the proposals would cut as many as 1,100 federal employees — and, to boot, would help reform and restructure a long-troubled Job Corps program that costs taxpayers $1.7 billion a year.

Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue made his case: Too many of the 25 CCC job centers were underperforming.

There was resistance from the start. The Job Corps has been a favorite of liberals going back to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s anti-poverty programs in the 1960s. The uproar was immediate and loud, and Baldwin helped lead the fight.

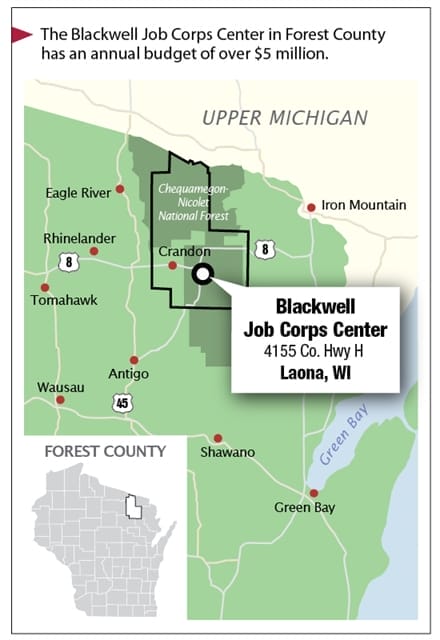

Laona center targeted

One of the centers on the chopping block was the Blackwell Job Corps Center in Laona in Forest County. Baldwin, with a political base in the Democratic strongholds of Madison and Milwaukee, saw the political calculus: Stopping the Blackwell closing would help her with voters in Trump country in the North Woods.

The surprise was Duffy, long a deficit hawk and proponent of a balanced budget. Closing nine facilities in a problematic federal agency and reducing the federal payroll should have been right in his wheelhouse.

But 55 of those targeted federal employees were in Duffy’s district, which covers most of northern Wisconsin. Shutting down Blackwell would hurt the “blue-collar recovery” in the Badger State, the Wausau congressman argued in a statement to Wisconsin Public Radio in June.

The Baldwin-Duffy tag team took different approaches: The senator introduced legislation to block the closures and signed onto a bipartisan letter of opposition to the secretaries of labor and agriculture, while the congressman lobbied the White House itself.

“I’m working with the administration directly on this because there is a greater chance of success,” Duffy explained in his June statement. The congressman, who resigned on Sept. 23, did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Baldwin.

The concerted outcry worked. In June, after a month of protests, the Trump administration reversed its decision.

Politics appears to have played a part in the backtracking: Many of the centers set to close were in states carried by Donald Trump in 2016, including Arkansas, Kentucky, Montana, North Carolina and Wisconsin. And those centers were in rural areas, bastions of his support.

Audits expose ineffectiveness

Unquestionably, the Job Corps’ objective is laudable: Give poor kids, teenagers in foster care and youths with difficult home lives free vocational training. At the Job Corps centers, disadvantaged youths learn skills at taxpayer expense with the aim of getting them jobs as carpenters, welders, masons, construction laborers and health care workers. The rural CCC centers train youths as first responders to natural disasters such as wildfires and for other jobs in rural areas.

The free vocational training for the nearly 50,000 students in Job Corps programs — with about 3,000 at CCC centers — is not free, though. U.S. taxpayers pay between $15,000 and $45,000 per student trained, according to estimates.

Whether taxpayers are getting a good return on their investment is highly questionable. Government audits over the past decade have skewered the program as ineffective and unsafe for too many students and raised questions that positive performance reports by the agency itself were the result of cheating.

Even President Barack Obama saw the need for reform, with his administration closing three underperforming Job Corps centers, including one in Florida where a student was hacked to death by other students in 2015.

Last year, a Labor Department inspector general report savaged the entire program. “Job Corps could not demonstrate the extent to which its training programs helped participants enter meaningful jobs appropriate to their training,” the audit concluded.

Private contractors working for the Job Corps did not provide students with effective help in obtaining jobs: More than half of the random sample of graduates in the audit were placed in jobs similar to their previous work, including some who returned to their old jobs, the report found.

“Finally, Job Corps contractors could not demonstrate they had assisted participants in finding jobs for 94 percent of the placements in our sample,” the report continued. “Participants either found jobs through their own efforts or without clearly documented contractor assistance.”

The inspector general noted that the Job Corps paid contractors $50 million over a two-year period for transition services. “But we found insufficient evidence demonstrating they had provided the services required by their contracts,” the report concluded.

That highly critical study followed similar audits over the years, including one in 2011 that found that the Job Corps placed graduates in jobs unrelated to their training, found jobs for them that required little or no training — such as fast-food cooks and dishwashers — and “in general overstated the success of its job placements.”

Some of the data in the 2018 study is horrendous.

Job placement failures

The inspector general’s office followed the careers of more than 230 students trained in the Job Corps and found that five years after graduating, trainees were earning a median annual income in 2016 of just $12,105, or around the poverty level. By comparison, the median annual income for individuals without a high school diploma or equivalency degree was $26,988.

Fifty-four percent of the graduates saw no improvement in the types of jobs they landed after the training, the study found. It cites as an example a fast-food cook who took Job Corps carpentry classes for nearly a year and then could only find a job as a pizza waiter. Five years later, the graduate was working at a convenience store earning $11,000 a year. “Job Corps reported this as a successful graduation and placement,” the study noted.

The study is replete with similar findings of Job Corps students returning to their same employer after graduation. A retail store cashier spent 310 days in the Job Corps learning how to lay bricks, graduated and then returned to the same store as a stock clerk — again, listed by the Job Corps as a successful graduate and placement, the study said.

Year after year, inspector general reports and audits by the government’s General Accounting Office (GAO) have pointed out serious mismanagement at the Job Corps.

A GAO study last year found more than 13,000 safety and security incidents involving students from July 2016 to June 2017, with 48% of the incidents involving drugs and assaults. Twenty-one students died in 2016, with two of them homicides, the study noted. The GAO found over 49,000 safety and security incidents since 2007, including 265 deaths.

U.S. Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.), who as head of a congressional committee on education and the workforce, has been a sharp critic of the Job Corps. She supported Trump’s original closure plan, calling the changes “an important first step in reforming the program so that it actually works.”

“The failures of the program do a disservice to students, staff and the American taxpayers who pay for the programs,” Foxx said on the House floor in June.

“There is ample documentation about the systemic deficiencies in Job Corps, and over 30 different government reports and audits have raised concerns over the safety and security of participants,” she added.

Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute and editor of DownsizingGovernment.org, agrees that the training centers are ineffective. “They’ve never worked very well or at all,” he says. “Federal auditors have always been a bit dubious of them.”

Edwards co-authored a 2011 study that found multiple, overlapping federal employment and training programs — 47 in all — and concluded that federal job training laws were more “political symbolism” than any genuine help. “The programs provide only marginal benefits at best,” the study found.

Its bottom line: Politicians support such training to look as though they are helping, whether the programs work or not.

Supporters value Blackwell

The news in May that the Trump administration planned to close the Blackwell center in Laona hit the area hard.

“Blackwell has a budget in excess of $5 million,” says Mark Ferris, president of the Forest County Chamber of Commerce. Much of that money is spent locally by the center’s students and 50-plus employees, he says. The center, which opened in 1964, has a capacity for 127 students.

“In a county of our size, 9,000 people, a facility such as Blackwell is very important,” adds Ferris, who owns the Little Pine Motel in Hiles. The announcement prompted some staff and students to leave, he says.

Craig Wolfretz, the center’s acting director, confirms the departures, saying the August enrollment was 61 students. “That is down from May,” he says.

He also acknowledges that some employees left recently but said that was due to planned retirements. Asked for the current staff total, he said, “I really cannot comment any further.”

Wolfretz emphasizes that keeping Blackwell open is important, both for its students and the local economy. “The key point is the validity of Job Corps,” he says. “The opportunity it provides youth to obtain training … the positive impact it has on the community.”

In June, when Blackwell learned of the administration’s reversal, staff members shared the news via intercom to students in the five dormitories.

The students were “super excited,” says Lorie Almazan, a guidance counselor at Blackwell for the past 17 years. “Then they knew they wouldn’t get kicked out of their dorms.”

In the Job Corps, students learn at their own speed, depending on the career and the pace students set for themselves. A graduate can spend 18 months or more in the program.

Almazan is cautiously optimistic that the reversal will hold, noting that the feds’ official statement used the phrase “for the time being” on keeping the centers open. “There was no guarantee,” she says.

Programs hard to cut

The failure to close Blackwell and eight other underperforming Job Corps centers as a way to save money echoes the administration’s losing skirmish two years ago to scrap a $300 million Great Lakes Restoration Initiative — a battle also lost because of blowback from Republican members of Congress.

Arguing that the program was duplicating state efforts and could be eliminated without hurting the environment, Trump budget-cutters included the Great Lakes initiative as part of $2.6 billion in cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The proposed cuts sparked an intense lobbying effort to save the initiative that included Democrats, environmentalists, bureaucrats, and tourism and outdoor groups. And joining them? Mike Gallagher, Glenn Grothman and Jim Sensenbrenner — three Republican congressmen from Wisconsin who in the past have lamented the ballooning federal deficit.

President Ronald Reagan ran into a few buzz saws himself trying to reduce federal agencies during his two terms in the 1980s. “A government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth,” Reagan quipped. “Government programs, once launched, never disappear.”

Copy down that quote and send it to the bruised budget-cutters in the Trump administration trying to shut down underperforming Job Corps centers.

Dave Daley is longtime Wisconsin journalist.