Family-owned for five generations, company thrives with its inclusive team approach and commitment to environment

ON THE FRONTLINES

Berlin — Brandon Hess runs a large sand mine in south-central Wisconsin, yet his two young sons don’t even have a sandbox in their back yard.

“I deal with it enough,” Hess says as he scuffs sand off his boots before swinging up into his pickup truck on a recent sunny spring day in the heart of the Badger Mining Corp. mine in nearby Fairwater. “The sand gets everywhere. It’s messy,” he joked.

But to Hess, the silky silica is also golden. It has run through the veins of his family for five generations and spurred a resurgent economic boon across Wisconsin’s Driftless Area.

The area — which spans Minnesota, northwestern Illinois, northeastern Iowa and Wisconsin, where it sweeps along its western side from Burnett County and into the south-central region — was never glaciated and holds a mother lode of sandstone. Because of the unique geology, experts say, the mineral deposits yield the best industrial sand on the planet.

Consumers often don’t realize that silica is in myriad common products — from toothpaste to glass to deodorant to bath tubs. It turns out that silica is also the ideal material for propping open fractures in shale made when “fracking” for natural gas and oil.

Around 109 million metric tons of silica sand were produced in the United State with a value of $8.23 billion in 2014. Of that, Wisconsin contributed 38.3 million tons valued at $3.15 billion — making the Badger State the nation’s largest producer of fracking sand.

That translates into thousands of jobs and 92 active industrial sand facilities in the state, mostly in western and central Wisconsin, according to the state Department of Natural Resources.

Badger Mining has long been one of the biggest and most successful of those companies.

Roots go back to 1800s

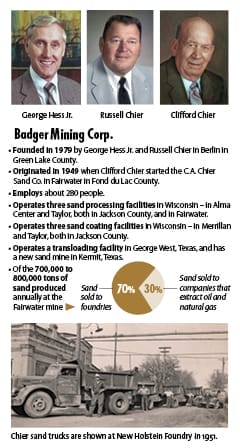

Brandon Hess’ grandfather, George Hess Jr., co-founded Badger Mining in 1979 with brother-in-law Russell Chier (pronounced “shire”). But the families’ mining legacy dates to the 1800s, when Russell’s grandfather, Michael, toiled in bank sand mines. He established his own mine in Berlin in 1900.

Michael Chier’s sons followed him into the business.

Son Clifford started his own operation, C.A. Chier Sand Co., in 1949, when he saw the opportunities created by foundries shifting from bank sand to silica sand for their castings. He purchased a burned-out sand plant in Fairwater, 20 miles south of Berlin, which was sitting on a large deposit of sandstone.

At the time, the mine encompassed about 20 acres. Today, the total mine — open pit, production facilities and, the largest chunk, reclaimed land — covers about 900 acres.

Clifford’s son Russell and son-in-law, George Hess Jr. (who married Russell’s sister, Sharon), learned the business from the ground up. Like Clifford, they saw opportunity.

When the Fairwater mine was purchased, hydraulic fracturing (now commonly called “fracking”) came into use. Sand was a key ingredient in the process, and over the years, it became clear the Upper Midwest’s sandstone silica was the perfect size, shape and hardness for the job.

With that market in mind, Russell Chier and George Hess Jr. purchased their next and largest mine — in Taylor in Jackson County. They purchased the land in 1978 and opened the mine in 1979.

While Wisconsin sand is the best in the world for fracking, there is one drawback. It’s far from the oil and gas fields, creating competition in places like Texas.

While Texas “dune” sand is inferior in quality for fracking and more of it needs to be used compared to Wisconsin’s sand, it is far cheaper — mainly because of the high cost of transporting sand from the Midwest.

“When they buy a ton of sand down in Texas that came from Wisconsin, it costs more to get it there than the actual cost of the sand,” says Mark Hess, who is George Hess Jr.’s son and Brandon’s father.

Badger Mining, as a result, operates a transloading facility in George West, Texas, and has a mine in Kermit, Texas, which will begin operating soon.

Unique leadership structure

Keeping the business in the family has been a priority for Badger Mining. Yet, unlike a lot of family-owned operations, the company uniquely incorporates non-family members into its top tier of decision-makers and does not equate family status with automatic employment.

It operates under a philosophy of collective management and is led by a four-member advisory team, rather than a CEO or president. Two on the team are family members, two are not and each holds the same power. Helping the advisory team is an eight-member leader group, also made up of family and non-family members.

Mark Hess, who is on the four-member team, says every employee has a voice. A large display in the lobby at the Berlin headquarters includes photos of nearly every employee, many of whom have been with the company for three decades or more.

“When you come in the front door and you look up on the wall and you see all the associates of Badger Mining, that’s really who Badger Mining is,” Mark Hess says. “It’s not the four or eight people that are supposedly the ones in charge. It’s really all the people out in the plant making Badger what it is.”

That team approach began with Clifford Chier. He was known for sitting down with his lunch pail in the mining plant on Fridays with all the workers and hashing out the week’s events and seeking the miners’ ideas.

Russell Chier and George Hess Jr. continued the tradition, although the ritual morphed into an after-work case-of-beer and bottle-of-brandy affair.

Friday evening beer and fish fries at the local tavern with Russell Chier and workers weren’t uncommon, either, longtime employees say.

At one point in the company’s history, it tried the traditional top-down, CEO model, but it was short-lived. The owners opted for the team approach.

“That’s actually the way Cliff operated back when he was at the plant,” Mark Hess says. “It’s really a way for us to get back to our roots and operate the way we had ever since the beginning.”

“Nobody is going to be given anything (only because) they’re in the family,” he adds. “They have to earn any position that they would get.”

Six percent of the current Badger Mining workforce are third- and fourth-generation family members. The company understands, though, that it has to grow and plan for the future. Many of its approximately 280 employees are in their 50s and 60s.

A fifth-generation potential employee is now an eighth-grader, says Deanne Bremer, a Fairwater operations coach and a fourth-generation Chier.

The company has a summer program for high school family members interested in the business. They shadow employees in all facets of the operation to see what interests them most.

Environmental stewardship

While Badger Mining’s business model and culture have drawn praise, landing the company on several “best places to work” lists, the nature of its work has drawn criticism.

Mining operations often cause consternation among neighbors who fear water and air pollution, health concerns or noise and traffic issues. Some environmental groups oppose natural resource mining for many of the same reasons and because they view it as stripping and permanently damaging the land.

Silica sand mining ventures get a black eye for their connection to oil and gas drilling, says Nick Bartol, Badger Mining’s government and public relations specialist.

“We’re not the prettiest industry; we realize that,” he says. “So we try to be good neighbors. We donate quite a bit to our local communities. We are heavily regulated, and we strive every day to remain in compliance.”

Some mine operations are “environmentally irresponsible,” but Badger Mining has a commitment to the community and good practices, says Mark Hess.

“You can wreck the environment by going in mining, but there are ways you can effectively mine and do it in an environmentally friendly way,” he says.

The company uses “geomorphic reclamation” practices to restore the land after sandstone has been extracted, Bartol says. For instance, slopes and valleys are created in the mine for water to flow into. “We always say we are just a small time in that piece of land’s life,” he adds.

Sara Joyce, quality technical assurance leader and a 34-year employee, says that philosophy dates to the early days of Badger Mining. “We reclaim the land to better than or close to what it was before,” she says.

Mining is a heavily regulated industry in Wisconsin. Badger Mining has earned the DNR’s Green Tier designation for its operational practices, given only to businesses that exceed regulatory requirements and implement rigorous environmental management systems.

Brandon Hess, like his father before him, spent his childhood in the sand mines and appreciates the natural beauty of Wisconsin. They are part of who he is.

“The idea (of the company’s reclamation system) is that 150 years from now, you couldn’t even tell we were here,” he says. “I have a passion for that.”

Betsy Thatcher of Menomonee Falls is a freelance writer and a former Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter.