Climate change has been blamed over the years for the rise … and fall … and rise again of lake levels

John Swart says the lakefront property he has owned for 50 years on Windmill Beach in Oostburg, south of Sheboygan, has lost about 125 feet of beach over the past three years.

His neighbors — Ron DeTroye, his wife, Pamela, and their youngest son — have a waterfront home currently situated 15 feet from Lake Michigan. When the DeTroyes bought the property five years ago, they had about 200 feet of sandy beach, which is now mostly gone.

Across the lake, Michigan resident Dan Fleckenstein purchased a home with beachfront property on the Mission Peninsula in Grand Traverse County five years ago.

“When I bought this home, I was told its real value was the beach,” he says. “In fact, I was told the beach came with a house, which is lucky because my wife and I haven’t seen any sand in a couple of years.”

The same holds true on the eastern side of Michigan, where for more than 100 years Eric Tubbs’ family has owned property north of Port Sanilac on Lake Huron. Tubbs say he has witnessed wide fluctuations in Port Huron’s water levels throughout his lifetime.

“I’m pretty fortunate my house is built on a high bank,” he says, noting the current lake level is as high as he remembers it in 1986.

Climate change as culprit

The relatively recent rise in Great Lakes’ water levels has caused some homeowners, environmentalists and even journalists to sound the alarm that something terrible, unprecedented and potentially catastrophic is occurring.

In March 2019, for example, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel ominously reported that winter and spring precipitation will continue to increase until 2100, after which summer rains “should decrease by 5 percent to 15 percent for most of the Great Lakes states” because of climate change.

In January 2020, the newspaper reported that the past six years have been the “wettest on record,” causing rising lakes to “gobble up” the state’s beaches.

Contrast those reports with a two-part investigation the same newspaper published in July 2013, in which a 37-year-old member of Milwaukee’s South Shore Yacht Club claimed he had never seen water levels on Lake Michigan so low. The article’s author portentously added, “Nobody has.”

Later, the writer rhetorically asked, “So where did all the water go?”

His response? “This is not a story about climate change. It is a story about climate changed.”

And this: “An alarming piece of research in 2002 predicted a drop of about 4.5 feet in Michigan and Huron’s long-term average in the coming decades. … (but a 2010) study concluded Michigan and Huron’s average level in the coming decades is most likely to remain somewhere around a foot below the historic average.”

Instead, 18 years later, Great Lakes water levels are near record highs. And this past January, in a story about rising levels, a Journal Sentinel reporter wrote, “no one knows if this is the peak of Lake Michigan’s water levels, whether it will recede any time soon or rise even higher. Or if this is a new normal.”

No one? New normal? Not so fast.

‘Ignores science and history’

“The idea that the current high water levels in the Great Lakes must be directly and primarily attributable to human-caused climate change is presently popular, but it ignores science and history,” Jason Hayes, environmental director at the Michigan-based Mackinac Center for Public Policy, writes in an email.

“In the same sense, reporting that the current water levels are a new climate change-imposed ‘norm’ also ignores science and reality,” he asserts. “Let’s not forget that those who are today blaming climate change for high water levels often made the same frightening diagnoses and predictions in 2013, when water levels were at record lows.”

Even as early as 2008, researchers examining a century of water level data for lakes Michigan and Huron were concluding that the decline could signal climate change.

“Researchers in Michigan report new evidence that water levels in the Great Lakes, which are near record low levels, may be shrinking due to global warming,” Science Daily reported in January of that year.

“In the new study, Craig Stow and colleagues point out that water levels in the Great Lakes … have fluctuated over thousands of years. But recent declines in water levels have raised concern because the declines are consistent with many climate change projections, they say,” according to the report.

And in a floor speech in June 2013, U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) cited the then-low level of Lake Michigan and proclaimed, “What we are seeing in global warming is the evaporation of our Great Lakes.”

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources website, meanwhile, sticks to the facts: “Lake water levels can fluctuate naturally due to rain and snowfall, which varies widely from season to season and year to year.”

Although somewhat reassuring, it doesn’t take into account the very real threat of property damage and erosion wrought by high lake levels.

The natural cycles

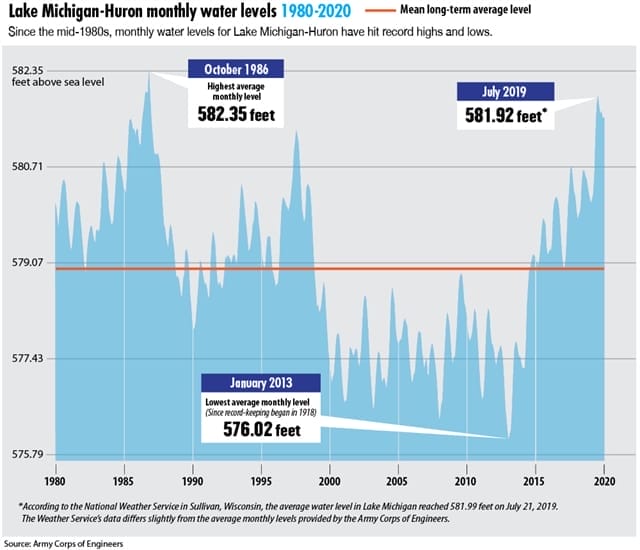

According to the Michigan Department of the Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, water levels in that state are the highest since 1986. Wave activity and heavy precipitation are causing erosion of properties that threatens houses and other buildings along the shorelines.

However, there’s plenty of evidence both anecdotal as well as historically and scientifically based suggesting that the Midwest isn’t transforming into a post-apocalyptic Waterworld.

“Although changes in water levels may be perceived as a problem for property owners, it is natural for lakes to go up and down in cycles that are decades,” the Wisconsin DNR says.

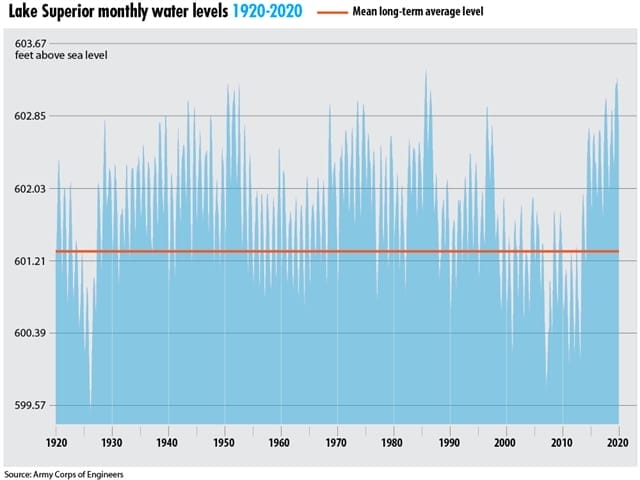

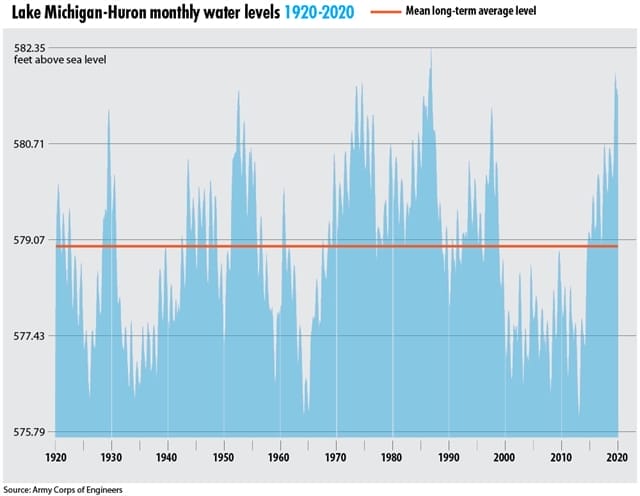

Ample historical data available from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Geological Survey display routine water level fluctuations, Hayes says.

For example, NOAA data from January 2020 shows the water level for lakes Michigan and Huron was 581.56 feet. “While very high, these levels were similar to the levels previously recorded,” he says, referring specifically to January 1860, November 1876, June 1886, July 1952, July 1973, June 1974 and July 1986.

Sediment core studies conducted by the Geological Survey in 2007 concluded the Great Lakes have experienced comparable fluctuation patterns from as early as 2600 B.C., Hayes notes.

Data shows pattern

The accompanying charts compiled from Army Corps data for the Badger Institute reveal a consistent pattern of fluctuations in Great Lakes water levels. In the past century, water levels on Lake Superior and lakes Michigan and Huron (hydrologically the same lake because they are linked by the Straits of Mackinac) correspond with anecdotal data from individuals possessing long family histories of life on the lakes.

In short: What goes up eventually comes down — and sometimes drastically so.

The long-term average monthly water level for Lake Superior ticks north of 601 feet above sea level. That, however, fluctuated from 599 feet above sea level in the 1920s to over 603 feet in the 1950s.

At an average of 579 feet above sea level, Lake Michigan’s level plummeted in the 1920s, 1930s, the mid-1960s and again in 2013; it rebounded each time. The record high was 582.35 feet in October 1986, while the level in July 2019 was slightly lower at 581.92 feet.

In January 2020, the Army Corps noted Great Lakes water levels were “above their long-term monthly averages” but predicted that Lake Superior would experience a 2-inch decline and water would rise an inch by mid-March.

Swart, who with his wife, Jackie, has lived full time at their lakefront home in Oostburg for 20 years, notes the historical record of Lake Michigan water level fluctuations.

“There’s a drawing from the Town of Holland from 1941 that has the lake levels from the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, and if the climate scenario is such that it goes back to those levels, we’ll be in trouble,” he says. “It was then two feet higher than it currently is.”

Tubbs concurs: “The water is absolutely higher, but if you live long enough, you’ll witness a lot of highs and lows. It wasn’t that long ago that Michigan was worried about low water levels.”

Bruce Edward Walker is Midwest regional editor for The Center Square. He has edited and written extensively on the environment and technology for more than 20 years. Wisconsin freelance writer Dave Lubach contributed to this story.

Related story: Environmentalism is a conservative value