Elections commission is confident that ballot tracking and barcoding will mean smooth and secure voting

If there’s any question come the early morning hours of Wednesday, Nov. 4, about whom voters have elected leader of the free world, there’s another query almost sure to follow:

Did the Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) and 1,850 local clerks do enough to ensure the integrity of the use of absentee ballots?

After the April primary, there were plenty of doubters expressing concerns about everything from lost absentee ballots to the possibility of ballot “harvesting” to fraud in the Badger State — one of very few key swing states that will decide the presidential election.

A record voter turnout here in the spring election drew national attention when it was learned that 144,185, or about 10%, of all the absentee ballots sent to voters, either were tossed out or never returned. Thousands more were requested but were never sent to voters at all.

The WEC responded with a 126-page report released on Sept. 1 outlining preparations for the Nov. 3 election.

“After the April election, we had some pretty major adjustments to make,” WEC Administrator Meagan Wolfe said in an interview in early September. “We had a lot to do on the front end for November. With our technology, cybersecurity and the human element — 1,850 local officials — we were able to address them. We Wolfe stressed that it was so important for people to act early.”

Tracking website, barcoding

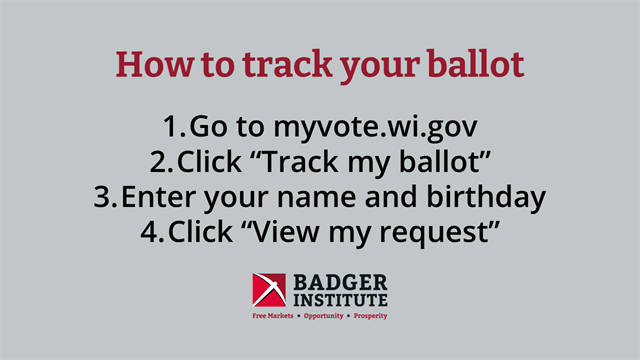

The two biggest adjustments were the creation of a ballot tracker called My Voter Info on the commission’s MyVote Wisconsin website and the use of intelligent barcoding on ballot envelopes to help clerks and voters track absentee ballots.

By requesting an absentee ballot on MyVote and registering, a voter is able to track the ballot in real time, from receipt of the ballot to its tally by a clerk, Wolfe said.

The commission did not have the authority to require all clerks to use barcodes, Wolfe stressed, and those clerks who do not use the state’s WisVote voter registration and election management system cannot take advantage of barcode tracking. Interest in using the system, which has had success in Colorado, increased significantly after the problems in April, Wolfe said.

One potential minefield — ballot harvesting — appears to have been sidestepped.

In June, Wolfe provided guidance to clerks that said, “A family member or another person may also return the ballot on behalf of the voter” — a stance that raised concern at the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty.

WILL sent a letter to Wolfe in June saying her recommendation conflicted with state election law that says absentee ballots “shall” be mailed by or delivered in person to the clerk by the person casting the ballot.

Harvesting has led to problems elsewhere. Election officials in North Carolina enacted reforms after they were forced to repeat a congressional election when they discovered partisans harvesting, or turning in, absentee ballots favoring the Republican candidate.

WEC member Dean Knudson, who in June failed to convince the commission to issue a statement condemning ballot harvesting, by September had backed away from predictions of harvesting in the presidential election.

Still, Knudson told Diggings he was strongly suggesting that, if possible, voters take advantage of COVID-19 precautionary measures in place at the polls and vote in person.

“We have a lot of ballot integrity safeguards, including voter ID in Wisconsin, more than there are in some other states,” Knudson said. “But there are more safeguards voting in person than there are voting absentee.”

Clerks expect crush

All told, between 1 million and 2 million Wisconsinites will cast an absentee ballot in November.

Wisconsin, unlike 10 other states, has resisted the pressure to mail ballots directly to all its registered voters.

The WEC did, however, commit as much as $2.2 million from a federal stimulus grant to send absentee ballot request forms and voter information to 2.6 million registered voters.

By the end of August, more than 1 million Wisconsinites already had requested absentee ballots.

The mailer with the absentee ballot application encouraged voters, who got their ballots as early as Sept. 17, to return them as early as possible.

Clerks anticipating a voter surge in November have, in the meantime, reported to the WEC that they ordered more absentee ballots early and have considerably increased the number of polling places where voters can drop off absentee ballots as well as vote in person.

By mid-fall, some fears about the November election process had abated.

In June, for instance, Knudson told The Center Square, a conservative news website, “If you think there’s no ballot harvesting in Wisconsin, buckle up because there most definitely will be.”

Less than three months later, he was no less adamant that people will be perfectly safe voting in person. But his views on the potential for ballot harvesting and other forms of fraud had softened considerably.

“Let me be clear about this,” Knudson said. “I have confidence in our process. It is very difficult to commit ballot fraud in Wisconsin. Not impossible, but difficult.”

In the weeks before an acrimonious presidential contest, confidence was high that all of the advance preparations will mean not only a more efficient but more honest and accountable election.

If that confidence isn’t justified, add the Wisconsin election to what almost certainly will be the most picked over and fought over presidential election of our time

Mark Lisheron is the managing editor of Diggings. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.