Claims that the streetcar swayed major development decisions in downtown Milwaukee are off track

At a press conference last fall, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett announced that in the three years since city officials approved the $128 million streetcar project, a.k.a. The Hop, assessments of properties within a quarter-mile of its 2.5-mile route have jumped nearly 28%, to about $3.95 billion. That compared with a 13.4% increase citywide.

During the press conference, held at a Hop station at the corner of North Broadway and East Wells Street, Barrett said the streetcar was the catalyst behind the $862 million surge in valuations within the defined areas since 2015.

“You can call it causation, you can call it correlation,” he said. “I call it investment. Because what we are seeing and what we have experienced since we first passed the file that created the streetcar is a nearly 28% increase in valuation of properties located within a quarter-mile of the streetcar.

“What does that tell me?” he continued. “It tells me that there’s keen interest in economic development along the streetcar line. It’s something we anticipated, something we had hoped for and something we had planned for as well.”

With a construction crane and concrete pillars visible behind Barrett at the site of the BMO Tower development and with streetcar tracks nearby, the optics were picture perfect. But Barrett’s assertion was anything but, a thorough examination reveals.

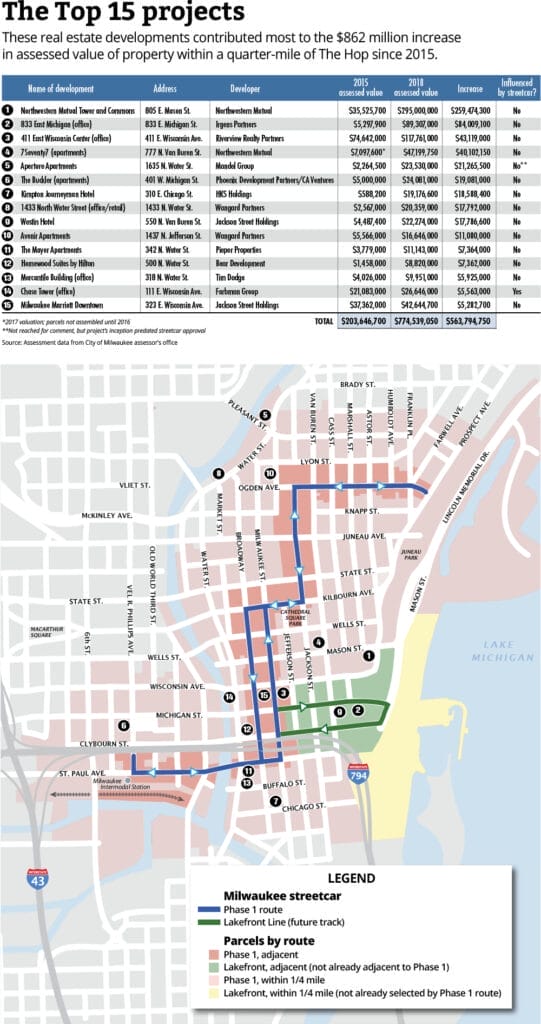

To test Barrett’s claim, the Badger Institute reviewed the 15 real estate projects that contributed most to that $862 million valuation increase. In all, those 15 large projects — which featured either new construction or significant renovations to existing buildings — generated nearly $564 million of the gain, or 65%, based on figures provided by the city assessor’s office.

The review was followed by interviews with all but one of the 15 developers. The result: 14 of the developers — whose properties generated over $558 million of the $564 million increase — say The Hop did not influence their projects. (See map and chart at the end of article.)

In some cases, in fact, the projects were in the planning stages or already underway before the streetcar was approved in 2015.

The bottom line: The Hop had no influence on almost two-thirds of the $862 million increase in property valuations since 2015. And the vast majority of the remaining third was spread over hundreds and hundreds of smaller properties throughout downtown that arguably could not have been affected much, if at all, by The Hop.

The mayor’s office did not respond to emailed requests for comment about the Badger Institute’s findings.

(Since the press conference last fall, the city assessor’s office has revised the overall property assessments in the defined areas to about $3.99 billion, which amounts to a three-year valuation increase of $907 million, or 29.35%. The change does not significantly alter the Badger Institute’s findings.)

Long-running controversy

The Hop, which began running in November 2018, has been a lightning rod for controversy since Barrett first proposed it more than a decade ago.

Consisting of five electric-powered streetcars, The Hop runs from the Historic Third Ward between the Milwaukee Intermodal Station, 433 W. St. Paul Ave., and Burns Commons, at East Ogden and North Prospect avenues.

Passengers ride for free during the first year, thanks to a $10 million sponsorship by Potawatomi Hotel & Casino.

Two federal grants funded about half of the streetcar’s construction costs, and another $59 million is expected to come from three tax incremental financing districts.

The streetcar’s future has been clouded because planned expansion of the route is largely dependent on federal funding, which never is a sure thing. In addition, a key component — the proposed $122 million Couture high-rise apartment project near the lakefront on East Michigan Street — remains in limbo.

Plans for The Couture include a transit concourse through which The Hop would pass on its as-yet-unbuilt Lakefront Line. The Couture’s developer, Barrett Lo Visionary Development LLC, still is waiting for U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development officials to approve a guarantee for the project’s construction loan.

Moreover, The Hop’s ridership already has faltered. After better-than-expected numbers in November and December, ridership fell sharply in January to 49,501, compared to about 76,000 during its first two months, a 35% drop. Ridership figures from February and March weren’t compiled, thanks to a glitch in an automatic passenger-counting system.

No influence cited

It’s no surprise that the property with the biggest three-year valuation jump is the Northwestern Mutual Tower and Commons at 805 E. Mason St., with a $259 million increase. Northwestern Mutual officials confirmed the obvious: The project was in the works well before The Hop was approved, thus nullifying any potential impact on the decision to build.

The same is true for another big-ticket development, the 833 East Michigan office tower, whose property valuation rose $84 million. But developer Mark Irgens, owner of Irgens Partners and who expressed support for The Hop while speaking at Barrett’s press conference, says the streetcar didn’t affect his decision to build the tower. Ditto for his decision to build the $132 million BMO Tower now under construction at 790 N. Water St.

“Public transportation, and transportation infrastructure in general, is really important to our business,” Irgens told the Badger Institute. “With respect to the streetcar, I’m very positive about it … I think it’ll be good for downtown as it expands and goes to more destinations.

“But to be truthful, the BMO and 833 projects were not affected by the streetcar,” he admits. “We made those decisions based on our assessments of market demand and working with tenants that wanted to sign (rental) pre-commitments with us.”

On the other hand, Irgens says, many tenants view the streetcar as a nice amenity — but not so nice that they’re willing to pay higher rent to occupy a building located right on The Hop route, rather than occupy one a block or two off the route with lower rent.

“I give the city a lot of credit for having a vision and taking a risk with the streetcar,” he says. “As it expands, I think it will be a much more impactful system.”

Developer Stewart Wangard, owner of Wangard Partners, says the streetcar did not influence his decision to develop two properties on the northern end of downtown: the 1433 North Water Street building (the site of the old Laacke & Joys sporting goods store) and the Avenir Apartments/retail building at 1437 N. Jefferson St. The three-year valuation increases for the properties were $17.8 million and $11.1 million, respectively.

Nonetheless, Wangard says he supports The Hop, and public transportation in general, provided it runs on time and is cost-effective. “I do think the Hop will benefit us in the long term,” he explains. “But the current route is too short to meet the needs of someone who wants to get around the city on a regular basis.

“It won’t realize its full potential until the terminus at Michigan Street is completed … that’s the big link between business and tourism,” he adds. “Until they finish it out, it’ll be nothing more than a novelty.”

Tim Dodge, majority owner of Hanson Dodge, an advertising agency in the Third Ward, says the streetcar didn’t prompt him to don a developer’s hat and renovate and add onto a building at 318 N. Water St. The building now houses Hanson Dodge and other tenants. The property’s valuation increased $5.9 million.

“The Hop did not influence our decision,” he says. “I don’t think anyone looking to make multimillion-dollar real estate investments is looking to The Hop for (their project) to be successful.”

But like others interviewed, Dodge sees potential value, provided the route is expanded. “If you don’t do that, it’s worthless,” he says. “Either you’re all in or you’re not.”

Lured by other factors

John Mangel, chief executive officer of Chicago-based Phoenix Development Partners, says The Hop had no impact on the decision to turn the old Blue Cross Blue Shield building at 401 W. Michigan St. into The Buckler apartments. (Another Chicago-based developer, CA Ventures, partnered with Phoenix on the project.) The property’s valuation increased $19 million.

“Our project started way before the streetcar was even considered,” he says. “Quite frankly, we just looked at The Buckler building as a property we could get out of the recession at a very low basis, plus we loved the location.”

Ditto for Riverview Realty Partners of Chicago, which spent $17 million on renovating the 411 East Wisconsin Center office building before recently selling it to Middleton Partners, another Chicago-based firm. The building’s valuation rose $43.1 million.

“The streetcar didn’t influence our decision,” says Jeff Patterson, president and chief executive officer. “But it’s definitely a good thing for that area … and as it gets completed, I think it will cause more residential development downtown.”

Keith Jaffee, president of Middleton Partners, says The Hop played no role in the company’s decision to buy the 411 East Wisconsin building from Riverview. “We just love Milwaukee,” he says. “We’re a Chicago-based company, but we just love the market there and want to continue to support it — grow our footprint there.”

Other real estate developers contacted by the Badger Institute also confirmed that The Hop did not affect their development decisions downtown, but they declined to comment publicly.

The outlier

One developer in the top 15, however, gave The Hop a thumbs up in terms of influence on development decisions.

Andy Farbman, chief executive officer of the Farbman Group, a Michigan-based commercial real estate developer, says the streetcar was somewhat of a factor in his company’s decision to renovate the old Marine Bank building, known as the Chase Tower, at 111 E. Wisconsin Ave.

Based in Southfield, a Detroit suburb, the company bought the building for $30.5 million in 2016. The property’s assessment increased $5.6 million since 2015.

“Our decisions to invest capital in an asset are based upon many factors,” Farbman said in an email. “We were certainly aware of the improvements being made in public transit, and it was an added bonus.”

Does mass transit in general affect Farbman’s real estate development decisions? “Yes,” he says. “All types of transit are important factors when deciding upon development and location. Much of the workforce that our tenants and prospective tenants are focused on retaining rely on all sorts of mass transit.”

A prominent downtown developer, Joshua Jeffers, agrees with Farbman, noting that The Hop has strongly influenced his decisions about real estate development downtown. While the owner of J. Jeffers & Co. doesn’t have projects in the top 15, he’s been a vocal streetcar advocate.

In fact, at the mayor’s press conference, Jeffers said that since 2011, when the initial route for the streetcar was proposed, his company has purchased, built or is in the process of building approximately $132 million worth of properties at six different sites, all directly on the streetcar line.

“So far, they’ve all been very high-performing investments, and I’m excited to see how they do going forward,” he said. “This is a huge milestone for Milwaukee.” Repeated attempts to reach Jeffers for comment were unsuccessful.

De-emphasizing the numbers

While Barrett declined to comment for this article, Department of City Development officials downplayed the interpretation of the assessment figures.

“When those numbers were published, the way they were received was a little different than how we intended it,” says Dan Casanova, economic development specialist lead. “The 28% increase was supposed to be a minor point, but it’s what everyone picked up on.

“Our intention is to track these numbers over time … and see if they change differently than the rest of the city or downtown,” he says. “We think the majority of the impact will come in one or two years when projects along the route break ground and come online,” he adds. “(Media) reports that (the increased valuation) was due to the streetcar … that wasn’t entirely the case for every project. There’s never a single factor for why a project happens.”

As an example, Casanova cites the Milwaukee Riverwalk as a public-infrastructure project that created value and demand for properties along the Milwaukee River. “But it’s not the only reason people want to live and work by the river,” he says.

Several developers interviewed also question why the city cast the net of its review of assessment increases a quarter-mile in each direction from The Hop’s route. Moreover, the city included the area around the unbuilt Lakefront spur in its calculations.

Casanova says that in urban-development circles, a quarter-mile is considered the standard distance that people are willing to walk to get to their destinations after disembarking from mass transit.

Great expectations

Looking ahead, city officials and others are making big predictions about the streetcar’s potential impact.

Consider a brochure from Milwaukee Downtown/Business Improvement District #21, an organization representing downtown businesses. Titled the “MKE Streetcar Development and Investment Guide,” it extols the economic development potential within a quarter-mile of The Hop’s current and future routes:

By 2030, the city expects 9,000 new housing units, a 63% jump; 13,500 new residents, a 55% increase; 1 million square feet of new occupied retail space, a 31% boost; 4 million square feet of new occupied office/hotel space, a 28% gain; 20,500 new jobs, a 23% increase; and $3.35 billion of new development.

Should all of that come to pass because of The Hop, whoever is mayor in 2030 will have a good reason to hold a press conference. And perhaps this time, the assembled media will pause to make sure the numbers touted actually support the rhetoric.

Ken Wysocky of Whitefish Bay is a freelance journalist and editor.