Vol. 22 No. 5

Executive Summary

Like many states, Wisconsin is about to reduce its prison population through an early-release initiative as part of a strategy to address a state budget shortfall. While the details of the early-release plan are being finalized, it is expected that up to 3,000 inmates will be released from prison. Wisconsin currently houses 22,212 inmates in its state prisons. In addition, there are 71,407 offenders on either probation or parole. Unless changes are made in Wisconsin’s approach to probation and parole, it is likely that recidivism will offset any long-term savings.

Wisconsin’s criminal justice system is marked by a pronounced cycle of crime followed by incarceration followed by parole followed by repeated crime. Several statistics provide evidence of the revolving-door nature of the criminal justice system. In Wisconsin, 38.2% of offenders released from incarceration are convicted of a fresh crime within three years. Many of the offenders being incarcerated are on parole. In Wisconsin, approximately 25% of prison admissions were for offenders under active community corrections supervision at the time of their current offense. While the public likes to think that parole leads to rehabilitation, only 46% of the offenders leaving parole in Wisconsin in 2007 did so due to successful completion of their parole.

Clearly there is a potential payoff from efforts to reduce recidivism among offenders on probation or parole. A 2007 study by the Crime and Justice Institute estimated that properly executed rehabilitation and treatment programs targeted precisely at specific offender groups could reduce recidivism by 10%-20%. While such a reduction would tremendously benefit public safety, it would also save the taxpayers huge sums in avoided incarceration costs. For example, a 10% reduction in new crimes committed by active parolees over one year alone could save Wisconsin taxpayers an average of nearly $70 million in incarceration costs.

It is widely understood among criminal justice experts that new approaches to dealing with offenders in probation and parole are successful in reducing overall recidivism. Several states are ahead of Wisconsin in addressing recidivism in this population.

Wisconsin seems unprepared to reap long-term savings from its early-release initiative. It continues to operate a traditional system of dealing with offenders on probation and parole. The Department of Corrections employs a standard assessment tool to measure offender risk, which dictates the number of face-to-face contacts for each offender. However, recent studies are critical of supervision programs that place a heavy emphasis on the number of contacts to measure success. This, along with other research findings, calls for a shift in focus from simply measuring contacts to seriously reducing recidivism. Until probation and parole is focused on reducing recidivism, we should expect to see a continuation of the current revolving door at each end of Wisconsin’s correctional system.

In addition, research finds that reducing recidivism requires careful monitoring of the effectiveness of sentencing and treatment for specific offender groups. Wisconsin is currently ill-equipped to track effectiveness. While the Department of Corrections is pinning its hopes that its Integrated Corrections System will provide the necessary tracking, the system has been under development for several years and still is not fully functional. Even if this tracking system were in place, the Council of State Governments found that the Wisconsin Department of Corrections lacks the necessary capacity to analyze and translate the data. Without the ability to actively monitor and assess this data, it is unlikely that recidivism will be reduced.

This study recommends that Wisconsin make three fundamental changes in its approach to probation and parole. First, the system should recast its orientation to focus on reducing recidivism.

Second, Wisconsin should improve the state bid process for community corrections services and initiate performance-based contracts to oversee both public and private providers. Performance-based contracts would include precise benchmarks and outcome-based measures of recidivism and public safety.

Third, it should move away from a system in which the public sector is the primary service provider. In the public sector there will be few consequences suffered if recidivism is not reduced. Contrast this with a private-sector service provider for which remuneration could be directly tied to recidivism rates. It is logical that the private-sector provider has more incentive to actually reduce recidivism. The United Kingdom can serve as a model in that it has moved away from a predominantly public system to one in which both public- and private-sector providers service the needs of community corrections. This blend of public and private providers should be used in Wisconsin.

If these recommendations are adopted, Wisconsin stands a greatly enhanced chance of realizing a lower rate of recidivism and a savings to the taxpayers. If they are not, Wisconsin should expect that the early release of prisoners will result only in an increase in the number of offenders going through the revolving door that defines the current correctional system.

Introduction

Community corrections has its roots in local, community-based programming implemented by non-government organizations. Over the years, increased bureaucratic control, growing offender populations and burgeoning budgetary constraints have led to an increasingly “one size fits all” approach to community corrections management. This approach to offender management conflicts with the reality that these individuals come from a myriad of backgrounds and circumstances, and possess a wide range of needs. As such, the community corrections system struggles to provide meaningful interventions for the large number of people who come through the system each year. The time has come to make a careful assessment of the state of community corrections in Wisconsin and to implement needed reforms in the interest of public safety.

The Wisconsin probation and parole system is administered by the Wisconsin Department of Corrections (DOC) under the Division of Community Corrections (DCC). The DOC reported an average daily population of 71,407 offenders under community corrections supervision in fiscal year 2007-08, an increase of almost 6,000 offenders from 1998. This number includes 53,581 probationers and 17,726 parolees. The Division of Community Corrections currently has 1,248 agents assigned to the supervision of probation and parole, each shouldering a caseload of approximately 60 offenders.1 For purposes of this paper, use of the term “parole” shall refer generally to all forms of post-incarceration supervision, including “parole” and “intensive sanctions” under indeterminate sentencing, and “extended supervision” as part of a bifurcated sentence.

At 17,726, the number of parolees in Wisconsin is higher than the national average of 14,633 and promises to increase.2 Record levels of incarceration have turned into record numbers of offenders being released from incarceration each year. As of the end of February 2009, 22,212 inmates were serving sentences in Wisconsin, and almost all will be released to the community corrections system.3 In FY 2007-08, 95.5% of all offenders released from Wisconsin prisons were placed into some form of community corrections supervision.4

Tougher crime policies and Truth-in-Sentencing have necessarily contributed to Wisconsin’s mounting corrections population. From 1989 through 2008, prison populations increased by 254%.5 Correspondingly, expenditures for criminal justice and the DOC also continue to increase. Spending on adult corrections rose from $495 million general purpose revenue (GPR) in 1998 to $974 million GPR in 2008.6 The total proposed corrections budget for FY 2009-10 is nearly $1.3 billion (approximately $1.15 GPR).7

The Problem of Recidivism

Costs to Society and Threat to Public Safety

Based on DOC data, 38.2% of offenders released from state prison in Wisconsin commit a new offense within three years.8 Consider also that this rate does not include offenders returned to prison for probation or parole revocation, offenders who have not been apprehended for a new crime committed, or criminal convictions in other states or under federal law.

A prison sentence may keep individuals from re-offending while incarcerated, but research shows that prison alone will not reduce recidivism.9 It is for this reason that community corrections programs are vital to reducing rates of re-offending. Reducing recidivism must be the measure of success to which we hold Wisconsin’s community corrections system accountable. This not only requires that individuals be prevented from re-offending while under community supervision, but also that they receive the necessary interventions to refrain from re-offending once the period of supervision has ended. Studies show that an offender’s involvement in the justice system could provide motivation for a change in behavior, but the system must do its best to capitalize on the opportunity.10

An offender’s criminal past is the best indicator of future recidivism. An individual with one prior criminal offense will eventually go on to commit another offense approximately 39% of the time. A person with five prior offenses will go on to commit another offense 58% of the time. According to a study conducted for the Wisconsin Sentencing Commission, the number of individuals who recidivate as a percentage of the overall DOC population has steadily increased since 1980.11 Once an offender has entered the system, the opportunity presents itself to influence the likelihood of re-offense. While under corrections supervision, offenders could be required to participate in programs such as rehabilitation, job training, and treatment to reduce their likelihood of committing new offenses once released. The system must be committed, however, to implementing recidivism-reduction programs to meet offender needs.

The 2009-2011 Budget included a provision whereby certain non-violent felony offenders will be considered for early release from prison and placed under community supervision. This would further increase the number of offenders supervised under the community corrections system. This provision is intended to free up resources to focus on higher-risk offenders. While this might create short-term savings, without making the necessary reforms within the community corrections system to reduce recidivism, it will only create higher costs in the long run as the cycle of recidivism wears on. For this initiative to have long-term success, the community corrections system must be re-energized with the purpose of protecting public safety and putting a stop to the revolving doors of our correctional system.

Researchers at the Pew Center on the States have found that states have not increased spending on community corrections in proportion to the increasing number of offenders on probation and parole. Instead, resources are being heavily allocated to prisons. While probation and parole are less expensive than prison on a per offender basis, continuing to increase prison budgets without giving proper funding to community corrections may be a misguided approach.12 While more funding might be needed to improve the current community corrections system in Wisconsin, the long-term effects will lead to a reduction in the overall corrections budget.

In 2007, the Crime and Justice Institute, in partnership with the National Institute of Corrections, released a white paper on methods to reduce criminal recidivism, authored by Judge Roger Warren of the National Center for State Courts. The paper estimates that properly executed rehabilitation and treatment programs targeted at the appropriate offenders could reduce recidivism by an average of 10%-20%, based on wide-scale research conducted on the subject. Some programs examined in these studies have achieved reductions in recidivism as high as 31%.13

In 2004, 62% of all state felony defendants had prior criminal convictions (and 46% had prior felony convictions). Nationally, around one-third of these defendants were on probation, parole or pretrial release at the time of their most current arrest.14 In fact, successful completion of probation in the United States dropped from 69% in 1990 to 59% in 2005.15

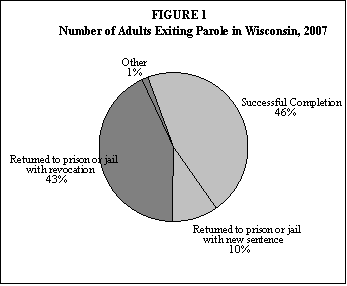

In Wisconsin, it is estimated that around 25% of prison admissions for new crimes are attributable to offenders under active community corrections supervision at the time of their latest arrest.16 Only 46% of offenders leaving parole in 2007 did so due to successful completion of the program, as shown in Figure 1. Most were returned to incarceration for revocation or new sentences.17

The Cost of Crime

The problem of recidivism comes with a serious price tag. The monetary costs of crime are easy enough to demonstrate, starting with those that rest on the shoulders of taxpayers. While Wisconsin shares the costs of criminal corrections with local and federal authorities, most of the burden falls to the state. According to 2007-08 figures, the average daily cost per inmate in Wisconsin was approximately $84 or $30,700 annually.18 Considering the current inmate population of 22,212, this adds up to almost $682 million per year in incarceration costs.

A snapshot of the Wisconsin prison population from July 2008 reveals that approximately 9% of inmates are admitted for violations of probation or parole.19 This accounts for $61.3 million in annual incarceration costs. Approximately 56% of the total prison population is made up of offenders who had at least one prior conviction at the time of their current offense.20 Thus, the cost of incarcerating recidivists in Wisconsin is over $381.8 million per year. This means that taxpayers are paying a total of $443 million annually to incarcerate repeat offenders and offenders who violated conditions of probation or parole.

Consider the 741 active parolees alone who were returned to incarceration in Wisconsin for committing new crimes in 2007.21 This translates to over $68 million in estimated incarceration costs attributable to offenders who recidivated in 2007 while under the supervision of the Wisconsin parole system.22

Because the costs of crime to victims involve so many non-monetary factors, they are not easily quantified. A 2005 report of the Wisconsin Sentencing Commission points to a study by Miller, Cohen, and Wiersema as “one of the seminal analyses of crime victimization costs.”23 The analysis uses the results of a national crime victim survey together with jury award figures to estimate categories including out-of-pocket expenses, lost wages, and non-monetary losses such as diminished quality of life. While the cost of violent crime can never be fully quantified by a dollar figure, the study provides compelling estimates of victim losses, a sample of which is shown in Figure 2.24

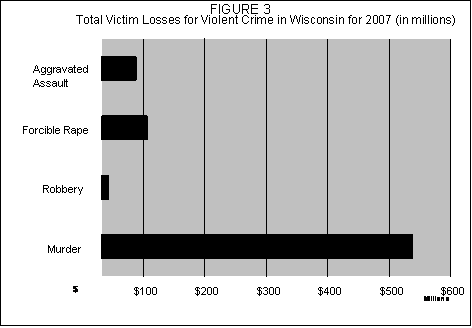

Wisconsin’s violent crime rate increased 23% between 2000 and 2007.25 Figure 3 estimates the total cost to Wisconsin victims for violent crimes perpetrated in 2007 in millions of dollars, based on the Miller, Cohen & Wiersema study at Figure 3. Combining all 16,290 cases of aggravated assault, forcible rape, robbery and murder, the estimated total cost to victims adds up to over $776 million dollars.

Even those who have never been victimized are saddled with additional costs to deter crime. Some examples from the Miller, Cohen & Wiersema study include private security expenditures, restriction of otherwise normal activity such as walking alone at night, lost productivity, and overall costs of maintaining the criminal justice system. 26

FIGURE 2

VICTIMIZATION COSTS BY CRIME

| Tangible Losses | Quality of Life | Total | |

| Fatal Crime (Rape, Assault, etc.) | $1,030,000 | $1,910,000 | $2,940,000 |

| Rape & Sexual Assault | $5,100 | $81,400 | $86,500 |

| Other Assault or Attempt | $1,550 | $7,800 | $9,350 |

| Robbery or Attempt | $2,300 | $5,700 | $8,000 |

| Arson | $19,500 | $18,000 | $37,500 |

| Larceny or Attempt | $370 | 0 | $370 |

| Burglary or Attempt | $1,100 | $300 | $1,400 |

| Motor Vehicle Theft or Attempt | $3,500 | $300 | $3,800 |

NOTE: All estimates in 1993 dollars.

Source: Miller, Cohen and Wiersema, 1996. “Table 2: Losses per Criminal Victimization (including attempts)”

Threat to Public Safety

While the monetary cost of crime is high, the cost to public safety is also of concern. The Wisconsin Office of Justice Assistance reported 176,155 violent and property crimes committed in 2007. Based on research showing that 62% of all felony defendants have prior criminal convictions, we can attribute an estimated 109,216 of these crimes to recidivists. Using a conservative estimate that 21% of all Wisconsin felony offenders were on either probation, parole, or pretrial release at the time of arrest, recidivists under active community supervision account for 36,992 violent and property crimes over the course of one year. A 10% reduction in crimes committed by recidivists would save Wisconsin from nearly 11,000 violent and property crimes per year.

Nowhere is the threat to public safety more apparent than in the analysis of violent crime statistics, which has been trending upwards in Wisconsin since 2004. 16,290 violent crimes were reported in Wisconsin in 2007, and many were a result of criminal recidivism.27 According to a 2006 Bureau of Justice study based on state felony defendants in the nation’s 75 largest counties, 56% of violent felons had at least one prior conviction; 36% of violent offenders were under community corrections supervision at the time of their arrest.28 These statistics provide insight into the number of criminal defendants who have already been through the correctional system at least once before.

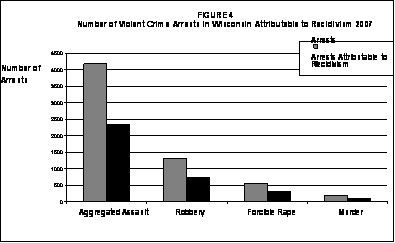

Assuming that the criminal histories of felony defendants in Wisconsin are comparable to these national figures, it is estimated that recidivism accounted for 3,488 of the 6,229 arrests made for violent crime in Wisconsin in 2007.29

As seen in Figure 4, that translates to approximately 2,336 aggregated assaults, 736 robberies, 313 forcible rapes and 104 murders in Wisconsin in 2007, over $3 million in estimated victim losses, without even accounting for the thousands of crimes reported for which an arrest is never made.

Even a 10% reduction in crimes committed by recidivists would produce tremendous benefits for the public safety. Based only on actual arrests made in 2007, a 10% reduction represents 417 aggregated assaults, 130 robberies, 56 forcible rapes and 18 murders in Wisconsin over the period of one year.

Pursuit of an Effective Community Corrections System

With high rates of recidivism continuing to plague correctional systems across the country, the issue has not gone unnoticed by policymakers and other stakeholders. A study conducted by the National Center for State Courts found that two of the most commonly voiced complaints of trial judges were high rates of recidivism and ineffectiveness of traditional probation in reducing recidivism.30 The study recognizes the urgency to reduce recidivism but also highlights the importance of community corrections in achieving this goal.

According to a recent article from The New York Times, researchers believe that “a focus on probation and parole could reduce recidivism and keep crime rates low in the long run.”31 An article in the Journal of Community Corrections similarly identifies probation and parole as key players in the pursuit of safer communities. Community corrections have the potential to utilize innovation and flexibility to promote the effective use of sanctions and resources.32

In May 2009, the Council of State Governments Justice Center released its report “Justice Reinvestment in Wisconsin: Analyses and Policy Options to Reduce Spending on Corrections and Increase Public Safety.” This report was developed upon request of Wisconsin policymakers to assist in the development of corrections policies to reduce spending and improve public safety. The report identifies revocations and recidivism as major drivers in the growth of the prison population and highlights specific weaknesses in the areas of community corrections and related treatment. The Council of State Governments (CSG) estimates that Wisconsin could save $2.3 billion over the next 10 years by implementing the appropriate policies and carefully targeting resources.33

What Works in Community Corrections

The community corrections system in Wisconsin is subject to increasing pressure to safely reintegrate growing numbers of offenders into society on a strained budget. Research indicates that supervision without treatment has no effect on rates of recidivism. Public safety goals are dependent upon improvements in factors such as substance abuse, employment, health, family relationships and accountability.34

In 2006, the National Center for State Courts asked state chief justices to rank sentencing objectives by importance. Included in this list was the promotion of public safety and reduction of recidivism through “evidence-based practices.”35 The use of evidence-based practices is widely regarded as the means to improving re-entry outcomes.

Evidence-Based Practice. There is broad agreement among experts that the principles of evidence-based practice (EBP) provide the framework for reducing recidivism through community corrections. These principles consider who and what should be targeted by a program, as well as how the program should address the needs of participating offenders. Other principles of EBP address the use of risk/needs assessment tools, motivation, and the integration of treatment with sanctions.

One of the most important principles of EBP calls for the accurate assessment of offender risks and needs. Treatment must then be carefully matched to an offender’s personal characteristics. As the risks and needs of an offender change over time, treatment must be modified accordingly through dynamic responses of probation and parole. In order for this to occur the system must be flexible, and a wide range of treatment and rehabilitation options must be available.36

The DCC uses a standardized assessment tool to measure offender risks and needs classification within the first 30 days of supervision.37 These classifications are then used to dictate the minimum number of face-to-face contacts required for the offender and to help determine agent caseloads. Wisconsin will need to analyze whether the resulting supervision conditions are properly tailored to the characteristics of each offender. Recent studies are critical of supervision programs that place a heavy emphasis on “outputs” such as number of agent-offender contacts, rather than on success-driven outcomes.38

When conditions of community corrections supervision are not well matched to the offender, it can undermine efforts to hold the offender accountable, which can be costly from a budget standpoint. A 2002 study in Ohio found that placing high-risk offenders in halfway houses decreased recidivism by 9% in comparison to regular community supervision. However, that same study found that low-risk offenders placed in halfway houses were more likely to recidivate because the treatment was not well matched to their needs.39 Research shows that imposition of conditions that are not directly related to the risks and needs of an offender can make it difficult to keep the individual in compliance with the truly essential conditions of his or her community supervision and can lead to costly revocations and re-offending.40

Alternatives to Incarceration. Applying the principles of EBP can help to unite supervision with appropriate rehabilitation and treatment programs. This is, of course, dependent on the availability of the appropriate rehabilitation and treatment programs. Community corrections agencies must have a varied range of meaningful options at their disposal.

The Planning and Policy Advisory Committee (PPAC) recommended a list of planning priorities to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 2006. PPAC was tasked with prioritizing critical issues facing Wisconsin courts. One of its recommendations was an increased focus on alternatives to incarceration, including mandatory drug treatment, diversion programs (for substance abusers and the mentally ill), victim-offender mediation and community service.41

Providing options not only allows community corrections to operate at the highest possible level, but enables the courts to lend their hand in the process as well. In State v. Gallion, 2004 WI 42, the Wisconsin Supreme Court affirmed that the framework of sentencing standards includes punishment and deterrence to others, but also protection of the community and rehabilitation. In considering sentencing options, courts must heed to the standard of McCleary v. State, 49 Wis. 2d 263, 276 (1971), that “[t]he sentence imposed in each case should call for the minimum amount of custody or confinement which is consistent with the protection of the public, the gravity of the offense and the rehabilitative needs of the defendant.”

The Wisconsin Supreme Court, in State ex. rel. Plotkin v. DHFS, et al., 63 Wis.2d 535 (1974), held that when determining whether to revoke probation, the state must exercise discretion to determine whether the offender is a “good risk” for continued community corrections. Two of the factors to be considered when considering revocation are whether the offender must be confined to protect the public, and whether the offender could continue to be successfully rehabilitated in the community.

This case law gives Wisconsin further incentive to pursue a meaningful community corrections system, and to provide options for sentencing and revocation decisions.

Where appropriate alternative sanctions or treatment programs are not available, decision-makers have no choice but to set aside recidivism-reduction strategies in order to protect public safety. This could lead to prison where an appropriate community corrections program might otherwise be desirable.42

Tracking Effectiveness. Also important in furthering EBP principles is the maintenance and analysis of outcome data. The program provider must be held to outcome-based standards, and failures and violations must be acted upon.43 By tracking successes and failures with an eye toward reducing recidivism, program providers can identify ways to improve operations. In 2006, the Wisconsin Sentencing Commission recognized the importance of tracking corrections data and included it in a list of recommendations to the state government, acknowledging that “sentences are most effective when they are tailored to specific offender groups.”44

Wisconsin does not currently have a system in place to broadly track sentencing and treatment effectiveness in relation to specific offender groups. According to the DOC, the Wisconsin Integrated Corrections System has been under development for several years and, once fully phased in, is expected to provide this tracking capability.45 However, the CSG study found that the DOC lacks the necessary capacity to analyze and translate the data collected by agency. Without this capacity, the DOC cannot expect to use the collected data to effect informed policy and spending decisions.46

Past and Current Efforts of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections

The 2009-11 Budget released by the Joint Finance Committee includes an annual $10 million GPR appropriation (the “Becky Young Community Corrections” appropriation) for the specific purpose of increasing public safety and reducing recidivism. The DOC would be required to use these funds to improve community corrections services toward this end. The recommendation would have the DOC correct gaps in service availability for offenders and develop accountability procedures. According to the Joint Finance Committee proposal, the annual GPR appropriation would be established for the DOC to provide or purchase community services to reduce recidivism for offenders on probation and parole.47

Taxpayers, policymakers, courts and other stakeholders must have assurance, however, that the DOC will be held accountable for achieving public safety goals. If these funds are rolled into the existing community corrections system, it is uncertain what improvement this would make and what recourse is to be had if recidivism continues its steady climb.

In an April 18, 2009 editorial, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel recognized that what the DOC has historically been doing is not working. “The state’s prison population is as large as it is – growing 14% between 2000 and 2007 and projected to grow 25% by 2019 – not primarily because of new crimes committed. It’s because the state and its communities have not come up with a better way to ensure that those under community supervision successfully complete it.”48

While the DOC may be suited to provide guidelines and oversight for community supervision services, the nature of a bureaucratic agency creates obstacles to accountability, ingenuity and efficiency. Wisconsin’s previous large-scale attempt to reform the community corrections system fell flat. In 1991 the Intensive Sanctions Program was enacted to divert offenders from prison to intensive community supervision. This program was backed by a six-fold increase in per offender funding yet failed to produce any measurable improvement in offender outcomes. One study revealed that despite DOC claims, the program was unable to protect the public safety, a finding that was punctuated by a 1997 murder committed by a program participant. Further examination of the program revealed program monitoring was inadequate, making an assessment of the program difficult and all but removing the means by which the program could be held accountable. In the wake of unfavorable evaluations of the Intensive Sanctions Program, and a series of high-profile crimes committed by program participants, the program was officially abandoned under Truth-in-Sentencing.49

In 1999 the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute released a report titled “Privatizing Parole and Probation in Wisconsin: The Path to Fewer Prisons.” The report addresses many of the same concerns that are reiterated in this current report: rates of recidivism in the neighborhood of 30%-40%, failure to track and evaluate the effectiveness of community corrections programs, and lack of agency accountability.

These exact concerns still exist a full decade later because stakeholders lack any significant means by which to hold the DOC accountable for its responsibility of protecting the public. As the Mitchell report observed, “to not hold community corrections accountable for reducing recidivism…is to relinquish the goal.”50

There is wide consensus among experts about “what works” in the field of community corrections. The challenge is safely bringing these solutions to the problem on a limited budget. Achieving these objectives will require efforts beyond business as usual.

The authors of “Putting Public Safety First,” a collective report by eight national parole supervision experts, warn that “those who wish to undertake the transformative change that these [evidence-based] strategies represent are cautioned to pay careful attention to the demands of implementation.”51 While the principles of EBP can be implemented here in Wisconsin, it will require initiative and strong leadership on the part of policymakers.

In a timely message for Wisconsin, the “Putting Public Safety First” report further cautions:

With states increasingly struggling to balance their budgets, and an ever-growing recognition that governments cannot bear the seemingly limitless costs of high incarceration and recidivism rates, legislators are beginning to consider innovative policies, such as earned discharge…to limit prison growth, increase public safety and reduce crime. Even with legislative support and initiative, however, the impetus remains on forward-thinking parole leaders and practitioners to advance a new public safety mission that incorporates these strategies for effective supervision.52

While it is imperative that state policymakers take the lead to establish, support and hold accountable a community supervision system that works, they must be met by a network of innovative community corrections providers that will carry the ball the rest of the way.

Advancing Community Corrections through Improved Partnerships

Wisconsin should be wary of utilizing taxpayer dollars, including the proposed $10 million Becky Young appropriation, to fund the current floundering community corrections system. Instead, funding should be allocated for the development of a broader and more effective network of public, private and non-profit service providers. This approach would meet the goals set forth by the CSG study to expand community-based treatment strategies while bolstering accountability.

While Wisconsin has increased funding for community-based programs by 45% since 2004, there is no system in place to monitor program quality, participation or outcomes, according to the findings of the CSG project, and rates of recidivism have not improved. Studies show that the cost of providing effective treatment programs is eclipsed by the economic benefits to society (an estimated $42,905 net benefit per offender, mostly as a result of crime reduction).53 However, without systematic assessments in place to measure the success of treatment programs, the state cannot effectively allocate its resources.

Improving and Expanding the Network of Private Providers

While the DOC currently contracts with private providers for certain community corrections services, there exists no analysis of whether this is money well spent. The CSG study identifies a continuing deficiency in program tracking and analysis in Wisconsin. The availability of more comprehensive program data would provide benchmarks against which to measure program effectiveness.

The current community corrections bid process is heavily weighted toward selection of the lowest bidder. A cheap but ineffective community corrections program may save money upfront but costs will manifest down the road in the form of re-incarceration and the sacrifice of public safety. It is for this reason that minimum standards, performance-based contracts, and program analysis are important to the accountability of community corrections services.

Performance-Based Contracts. Properly drafted outcome-based contracts are imperative in the area of corrections. The incentive for providers to operate with fidelity to recidivism-reduction principles must be clear, and contracts must insist upon it. Where performance-based contracts are used, the control belongs to the policymakers. A well-drafted contract could clearly spell out desired outcomes while largely leaving the means to these ends to the contractor, who could then find the best ways to meet recidivism-reduction goals.

Providers would be encouraged to use innovation to ensure the best combination of cost and quality.54

Most experts agree that performance-based contracts must clearly define success as the reduction of recidivism through the implementation of evidence-based practice. The state bid process must include strategic procurement rules that define specific outcomes to which the government can hold providers accountable, which would mean raising the bar on the minimum standards currently required of treatment programs.55

The cost of monitoring contracts for correctional services is low. An example can be found in expenditures made in previous years to administer private bed contracts. The DOC is authorized to contract with private companies for prison beds in other states, holding providers accountable by contracting for specific provisions with regard to cost, procedure and reporting. To monitor private prison bed contracts, the DOC relied on a small unit within the Division of Adult Institutions, which supervised private bed contracts while serving the additional functions of overseeing contracts with county jails, and processing transfer requests, detainers, warrants, extraditions, and security audits. The total cost of this monitoring unit was $756,800, only 5.3% of the GRP budget for the private bed contracting program as a whole for fiscal year 2007-08.56

Performance-based contracts are also a useful tool for defining reporting requirements to help meet the tracking goals outlined by CSG. Service contracts should require the collection of performance data as a matter of accountability, as both courts and policymakers need to possess relevant data in order to best measure program improvement and failures. Accordingly, this influx of data must be met with the ability to analyze it. The CSG recommendations suggest that while a state agency could provide this function, the state might also decide to bring in an outside organization to process and assess the data.57 The benefit of bringing in an outside group to perform this function is that it lends an extra level of fidelity to the process.

While improving the state bid process for community corrections services is a good place to start, more services are needed. As recognized by the recent Milwaukee Journal Sentinel editorial on the topic, the system is wanting for “more robust re-entry programs,” including more halfway houses, substance abuse treatment and mental illness services.58

The CSG study confirms the need for expansions in a range of evidence-based treatment programs.59 The private and non-profit sectors are poised to meet these needs. Increasing partnerships and encouraging competition in the areas of community corrections treatment could help Wisconsin to implement a broad range of the most efficient, cost-effective programs to further the goal of public safety.

Expanding Availability of Offender Assessments and Treatment

Offenders under community corrections can benefit from a variety of services, ranging from increased job training programs to social support networks. However, it is the presence of mental illness, substance abuse disorders, or both, that most heavily drives recidivism. Offenders with these issues are more likely than other offenders to recidivate and create public safety concerns, unless they receive effective and appropriate treatment.

Mental Health. As of June 2008, approximately 31% of all incarcerated adult offenders were identified as suffering from some form of mental illness. Nationally, it is estimated that only 12% of the 70%-85% of state inmates who need substance abuse treatment are receiving it, due in part to long waiting lists, lack of incentives to participate in treatment, and a shortage of trained providers. Judges often lack the tools needed to perform mental health assessments, and further lack outlets to available treatment.60

A March 2009 report by the Legislative Audit Bureau found that while Wisconsin regularly screens and monitors mentally ill inmates, treatment and programming is limited at some institutions. Despite a DOC directive for all facilities to develop a release planning curriculum, only nine of 20 institutions, and one of 16 corrections centers have fully implemented this curriculum, citing lack of resources and shortage of staff. The DOC reports that the state has difficulty recruiting and retaining psychiatrists for mental health positions. This has caused gaps in the availability and consistency of offender assessments and treatment. The DOC ratio of 345 inmates per psychiatrist is more than twice the American Psychiatric Association’s recommendation of 150 inmates per psychiatrist.61 As offenders transition from prison to the community, they bring with them the effects of inconsistent assessments and treatment in DOC institutions.

DOC officials and mental health advocates have raised concerns as to the lack of community treatment resources, particularly in areas of the state where county mental health services are unable to meet the need. The waiting list for county services in Dane County is more than a year long, and Milwaukee County’s walk-in clinic operates on a first-come, first-served basis, serving only 15 clients per day. As a result, most appointments in these counties were with DOC-contracted professionals and community providers. Even with access to state grants and support, county services cannot meet the treatment needs of the community corrections system. Counties without a greater depth of provider options beyond county services are therefore a source of concern.

While DOC staff report that they can usually arrange treatment appointments, a sample reviewed by the Legislative Audit Bureau found that only 62.5% of offenders with mental illness had documented post-release treatment appointments. The study also revealed that several of these offenders did not have their first appointment until more than three months after their release.62

In FY 2007-08, 2,420 mentally ill inmates were released from prison.63 Deficits in programming and re-entry planning for incarcerated offenders with mental illness and other treatment needs necessarily add to the corrections burden. The rate of recidivism among offenders with serious mental illness is 46%.64

Substance Abuse. National statistics show that 80% of state and federal inmates were incarcerated for alcohol- or drug-related crimes, were intoxicated at the time of the offense, committed the offense to support an addiction, or had a history of alcohol or drug abuse. Once offenders with substance-abuse issues are released to community supervision, the cycle threatens to repeat itself. Thirty percent of offenders show evidence of substance use within the first two months of release from prison.65 In 2007, 77% of offenders revoked from community corrections admitted to drug use while on supervision.66

Alcohol and drug treatment is an important issue as individuals transition from prison to community corrections. Experts recommend that periodic screening continue through an offender’s transition back into the community to avoid relapse and to identify problems that might not become apparent until an offender returns to the community. One study showed that post-incarceration treatment reduced recidivism by 7%.67

The recent CSG report notes that substance abuse and mental health assessments in Wisconsin are not consistent or compatible across the criminal justice system.68 While conditions of probation and parole include contacts with DCC agents, these agents function as case managers and for the most part are not trained to make psychological, behavioral or medical assessments of offenders. Because the state struggles to recruit and retain professionals to conduct these assessments, contractors from the private sector might be better suited to take a larger role in this process. Filling the gaps in the assessment process would create a more efficient system for matching an offender to the necessary treatment.

Even where the appropriate needs assessments are made, however, finding a program that is appropriate and available to a particular offender can be difficult without a diverse network of treatment providers. While agents can assist in connecting an offender with treatment resources, options throughout the state vary in quality and availability.

A National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices survey concluded that services provided by state correctional agencies have little impact on changing offender behavior without a commitment to providing programs to meet the needs of specific offender issues.69 While this means efforts beyond selecting the lowest bidder, the expertise of private companies and non-profits lends itself well to providing a variety of programs that might not otherwise exist in a particular jurisdiction, such as specialized treatment programs or options geared toward specific groups of offenders. A well-executed and carefully balanced supervision and treatment system will provide offender rehabilitation, further the goals of public safety, and improve judicial and public confidence in community corrections.70

One promising model for the improvement of treatment through partnerships outside of state agencies has emerged from a pilot program for mental health treatment. The Conditional Release Program, operated by the Department of Health Services (DHS), contracts with regional service providers for case management and support services to provide specialized community care for offenders found not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect. The effect of this program on recidivism is promising, with only 5% of Conditional Release Program participants returning to custody within three years of release. While this program requires upfront costs, the reduction in recidivism could create the type of long-term savings touted by the CGS study. A Legislative Audit Bureau report found that this model could be transferable to offenders transitioning into the community from prison.71

There is room for improvement in the area of offender mental health and substance abuse treatment, and drawing from a broad range of public, private and non-profit providers could fill the gaps to meet the needs of offenders in Wisconsin. Thorough tracking and analyzing of program data would hold providers accountable and ensure that the system is correctly allocating the limited resources available for treatment of offenders under community corrections.

Expanding the Role of Private and Non-Profit Providers

Currently, private and non-profit involvement in DCC operations is largely limited to the purchase of goods and contracts for certain services not available through the DOC. Opening the playing field to allow for complete participation of private and non-profit providers, in addition to existing public programs, would result in a more meaningful, robust system of community-based providers. This can be done by encouraging private and non-profit groups to participate in areas that need expansion as well as in areas typically reserved for state-run programs. Almost every aspect of community corrections operations could be examined to determine whether it could be more efficiently run.

By more widely opening the doors of the community corrections system to competition, Wisconsin might expect an increase in partnerships with private service providers, but also increased efficacy of government-run programs. The possibility of privatization alone could advance efficiency within the corrections system by raising the bar against which public providers are measured. Borrowing from examples in private prison operation, one study found that “whether from fear of being privatized themselves, or pride in showing they can compete, or from being compared by higher authorities, workers and management throughout the system respond to privatization.” 72

Exposing the probation and parole system to further aspects of competition could raise the standard of services in DCC operations and create openings for private and non-profit providers to exercise their innovation in the area. A more inclusive approach to community corrections would help ensure that only programs providing the best results at a competitive cost would be funded, and that ineffective programs, whether public, private or non-profit, would be discontinued. The field would be open to a diverse range of providers, advancing innovation and efficiency, and providing a means by which the system could be held accountable.

Wisconsin provides an ideal environment in which to implement this approach. The recent CSG study confirms that the state is at a crossroads in terms of corrections policy. Without the appropriate reforms to the community corrections system, recidivism and spending will continue to rise. The history of the state’s struggle to implement effective community corrections policies signals that Wisconsin would benefit from a new approach to help achieve the CSG policy recommendations.

Furthermore, studies suggest that private corrections operations have the potential to reduce costs, particularly in states where public employee benefit expenditures are high.73 The cost of Wisconsin’s public- sector benefits fits that bill, ranking 11th highest in the country. As of 2005, benefits per worker for Wisconsin public employees were 50% higher than for private employees.74

There is evidence to support the expansion of private and non-profit partnerships throughout Wisconsin’s community corrections system. These partnerships could go beyond traditional contracts for goods and services and reach into the offender supervision aspects of probation and parole.

Wisconsin’s halfway houses provide an illustration. The DOC contracts for beds at these community-based residential facilities for around $68 per day. State halfway house contracts accounted for approximately $13.3 million over FY 2007-08.75 Halfway house providers offer a range of comprehensive treatment, counseling and living skills services to improve re-entry outcomes for participants, while providing offender management functions to protect the public. The average size of a halfway house in Wisconsin is small to allow for personalized attention, and participants are often placed in facilities close to home. Halfway houses and the accompanying treatment programs have long been an integral part of Wisconsin community corrections. These facilities offer offenders the opportunity to receive treatment outside prison walls, where real-world situations present themselves.76

Halfway house staff members have specialized training and are available to work non-traditional hours. Participants in an international halfway house conference identified several challenges specific to the area, which include: identifying sites that will provide suitable accommodation for offenders, developing effective programs to reduce re-offending, providing adequate supervision to ensure the safety of staff and the public, educating staff to make effective interventions in the offender’s life, and contemplating gender-specific programming for a growing number of female offenders.77 Operators of halfway houses have highly specialized knowledge in these areas, and Wisconsin providers possess extensive experience in the field.

According to the Legislative Fiscal Bureau, 67% of offenders in halfway houses successfully complete the programming78, compared with the 45% that successfully complete parole under government-run supervision.

Halfway houses provide a unique glimpse into how partnerships with private and non-profit groups can lend expertise and experience to the community corrections system in Wisconsin, even in the delicate area of direct supervision of offenders. Because of the high demand for these services, however, waiting lists for placement in halfway house facilities are often several months long.79

Private Probation in Other States

At least 10 states have implemented some form of privatized misdemeanor probation programs as a response to mounting budgetary pressure. In a growing number of states, private and non-profit partnerships are used as the primary means for supervising misdemeanor probationers.80 While state governments retain ultimate responsibility for the supervision of offenders, private probation systems typically operate as a network of private probation management companies, community-based treatment providers, and other specialized companies (such as those providing electronic monitoring services).

Regional decision-makers decide which entities will provide misdemeanor probation supervision in their area, and control is largely decentralized to allow for local responses to community issues. Because county and local actors are the driving force behind probation and parole services, there is less bureaucracy in day-to-day operations, judges never lose control of the case, and community corrections are truly part of the community.81

Longtime community corrections professional Don Evans clarifies the value of community-based probation and parole:

One of the shifts in our business that is occurring is that probation and parole is becoming institutionally based and community placed…. I am referring to an institutional mentality, a bureaucratic mentality, a structure that occurs within society.

……………..

I suggest that a community-based or even better, a community-run system would have its responses from the community. This is a radical difference that allows for a lot more regional differences, for much more participation of the community, for more mitigating and mediating structures between the government and the problem it is trying to respond to.82

While privatization of misdemeanor probation exists in some places in the United States, this provides only a limited application of privatization to community corrections, and performance standards are not specifically geared toward the reduction of recidivism. It does, however, serve as another example of safe and successful privatization of the offender supervision function of community corrections.

Privatized Community Corrections in the U.K.

Policymakers in the United Kingdom have chosen privatization as the means by which to correct their community corrections system. Probation and parole services were once run by private institutions in the U.K. but eventually shifted to government-run programs. The reintroduction of privatization into community corrections is now the focus of a large-scale effort to reform the system. By the turn of the century, the U.K. was struggling with the rising costs associated with overcrowded prisons and high rates of recidivism. As in the United States, prison populations in the U.K. were at record levels.83 The proportion of all offenders that went on to commit new crimes within two years was 43.7%.84

The high cost of crime on society has driven policymakers in the U.K. to make more effective use of taxpayer money to reduce recidivism and improve public protection. In 2004 the government created the National Offender Management System (NOMS) to achieve these ends. NOMS put regional commissioners in place to manage the needs-based commissioning system at a local level. Commissioners enter into service agreements with both public-sector providers and private-sector contractors. Commissioners are able to decide how best to allocate resources based on the needs of offenders in their region, and to bring new service providers into the mix if appropriate. Regional NOMS commissioners are charged with contracting for services in their regions, developing an overall plan to reduce re-offending, and coordinating partnerships regionally and locally.85

As Helen Edwards, former chief executive of NOMS, explained:

We want to get a wider range of partners involved in managing offenders and cutting re-offending. Therefore, we will legislate to open up probation [and parole] to other providers, and will only award contracts to those who can prove they will deliver reductions in re-offending, and keep the public safe. We need to bring in expertise from the private and voluntary [non-profit] sectors to drive up the quality and performance of community punishments.86

Competition among providers creates more options and drives potential providers to innovate new solutions to achieve efficient results. Non-profits are heavily encouraged to participate in the system due to their varied subject-area expertise and community-based knowledge. Strengths of non-profits often include the diversity and experience needed to reach groups that government institutions find hard to connect with (including certain minority groups, drug users, and offenders with mental health concerns), and the ability to develop services from the bottom up to respond to the individual needs of offenders.

NOMS commissioners recognize the value of smaller organizations, which have the ability to be more flexible than large bureaucracies.87

Collaborative efforts have emerged among groups that specialize in specific areas of corrections to provide comprehensive solutions to meet NOMS outcome goals. Partnerships have formed consisting of private and non-profit groups, each providing different offender management functions including offender transport, education and training, community service opportunities, financial counseling, employment options, and accredited treatment programs.88 No single program can be expected to provide solutions to the complex and varied needs of offenders on community corrections. Not only do these collaborations offer a range of solutions, but they do so efficiently and through providers with specialized experience in particular aspects of offender management.89

Privatization of community corrections is having a positive effect on rates of recidivism in the U.K. As of the most recent studies, the rate of re-offending had dropped 10.7 percentage points, from 43.7% in 2000 to 39% in 2006.90

The key to the U.K.’s competitive commissioning system lies in outcome-based goals. All providers are required to demonstrate that they meet clear service-quality standards and statutory duties. Existing public providers are given the opportunity to show that required benchmarks are being met. Those unable to achieve well-defined performance targets are then exposed to competition from other providers.91

Payment is structured on recidivism-reduction results, and commissioners provide incentives for favorable performance. Outcome-based contracts encourage providers to carefully tailor services to an individual’s needs to reduce rates of re-offending and to advance public safety.

While providers are responsible for efficient service operations, the government is held accountable for using its resources to align the supply and demand of services to meet the needs of offenders. It remains the responsibility of the government to provide oversight through the careful assessment, contracting, management and review of providers.92

A Recommendation for Wisconsin

This report aims to address the need for community corrections reform through improved and increased partnerships with private and non-profit organizations to achieve maximum results on a limited budget. By improving and expanding the current state bid process, Wisconsin could benefit from the most effective and cost-efficient combination of public, private and non-profit providers. It is suggested that policymakers establish a realistic framework for reform and provide for oversight of the community corrections system to include the following considerations:

- Improvement of the community corrections bid process, including higher minimum standards and carefully drafted performance-based contracts to hold providers accountable. By structuring payment upon performance goals, and clearly specifying what is desired, the state will deter providers that are able to come in with a low bid but would be unable to meet the required goals.

- Definition of precise benchmarks and outcome-based goals established with an eye toward the overarching goal of reducing recidivism and protecting the public. By publishing these guidelines, all potential public, private and non-profit bidders will have an understanding of the requirements and principles under which they are to operate. Clear guidelines will encourage providers to apply their varied expertise and experience to deliver solutions. Precise standards will also yield realistic expectations of stakeholders.

- Creation of additional regionally based purchasers of goods and services managers from which the commissioning of service providers will be conducted to allocate funds (including the proposed Becky Young appropriation) for community corrections services. To decentralize the contracting process and encourage the use of community-

based solutions to achieve local results. While the state would retain ultimate authority, regional coordinators would have the discretion to choose how best to allocate resources to remain flexible and meet the needs of offenders in their area. - Formation of an impartial organization to track, manage and analyze program data. To identify successes and failures in terms of offender outcomes.

- Establishment of an enforcement plan. The means by which to hold providers accountable to contract performance and fidelity to the goal of reducing recidivism through evidence-based practice.

- Planning for transitional stages during which the private and non-profit sectors are allowed to bid against the DOC for increasing roles in offender management and other functions of community corrections currently controlled by the DOC. To allow time to carefully plan for the safe execution of these reforms and to modify the bid process to improve effectiveness.

This proposal is recommended as a means to further Wisconsin’s goals of recidivism reduction, budgetary control, and public safety. In a time of record corrections populations and burgeoning corrections budgets, Wisconsin has the opportunity to lead the nation in the pursuit of meaningful community corrections reform. By improving and expanding the community corrections bidding process, Wisconsin will either raise the standard of services in DCC operations, or encourage partnerships in which private and non-profit providers can bring new innovation, flexibility, options and expertise to the table.

Endnotes

1 Carmichael, Christina D., “Informational Paper 57: Adult Corrections Program” (Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January 2009), 1,17.

2 Glaze, Lauren E. and Bonczar, Thomas P., “Probation and Parole in the United States, 2007 Statistical Tables” (USDOJ Department of Justice

Statistics, 2008), 4.

3 Wisconsin Department of Corrections – Institution Populations, “Offenders Under Control on February 27, 2009,” available at http://www.wi-doc.com/index_community.htm.

4 Carmichael, 11.

5 Carmichael, 8.

6 Lightbourn, George, “Reforming Wisconsin’s Budget for the Twenty-First Century” (Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, 2003), 15 & Carmichael, Appendix III.

7 2009-11 Joint Finance Committee Proposed Budget, p. 276.

8 Simonson, Dennis, “Prison Release Recidivism (1980-2004) – source: DOC CIPIS and CACU Data as of 3/2/08,” March 3, 2008. Unpublished Report.

9 Semmann, Steven J., “Three Critical Sentencing Elements Reduce Recidivism: A Comparison Between Robbers and Other Offenders” (Wisconsin Sentencing Commission, 2006), 1-13.

10 Physicians and Lawyers for National Drug Policy (PLNDP), “Alcohol and Other Drug Problems: A Public Health and Public Safety Priority,” April 2008, 23.

11 Semmann, 9-10.

12 Moore, Solomon, “Prison Spending Outpaces All but Medicaid,” The New York Times, March 3, 2009.

13 Warren, Roger K., “Evidence-Based Practice to Reduce Recidivism: Implications for State Judiciaries” (Crime and Justice Institute & National Institute of Corrections, Community Corrections Division, 2007), 18.

14 Kyckelhahn, Tracey & Kohen, Thomas H., “Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2004” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2008), available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/fdluc04.pdf.

15 Warren, 1-10.

16 Pingel, Jim, “Report to the Data & Research Committee” (Wisconsin Sentencing Commission, February 2007), Table “Adult Offender Prison Admissions by Type and DOC Operating Budget.”

17 Glaze & Bonczar, 8.

18 Carmichael, 3.

19 Carmichael, 10 & Appendix VI.

20 Calculation of 62% (national percentage of state felony defendants with a prior criminal conviction) of the 21,515 inmates convicted of a new crime, as a percentage of the total Wisconsin prison population.

21 Glaze & Bonczar, 8.

22 Estimates based on the national average felony sentence length of three years from Durose, Matthew R. & Langan, Patrick A., “Felony Sentences in State Courts, 2004” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, July 2007), multiplied by the number of crimes committed by active parolees times the average annual cost of incarceration in Wisconsin of $30,700.

23 Key, Tori, “Cost-Effective Criminal Justice: A Survey of National Issues and Trends” (Wisconsin Sentencing Commission, March 2005), 3.

24 Miller, T.R., Cohen, M.A. & Wiersema, B. (1996), “Victim Costs and Consequences: A New Look” (DOJ, National Institute of Justice, 1996), 9.

25 Counsel of State Governments Justice Center (CSG), “Justice Reinvestment in Wisconsin: Analyses & Policy Options to Reduce Spending on Corrections and Increase Public Safety,” May 2009, 2.

26 Miller, 9-11.

27 Christianson, Kirstin, et al., “Crime in Wisconsin 2007” (Wisconsin Office of Justice Assistance, Uniform Crime Reporting Program, 2008a), 7.

28 Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Violent Felons in Large Urban Counties,” 2006, available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/vfluc.htm.

29 Christianson, Kirstin, et al., “Arrests in Wisconsin 2007” (Wisconsin Office of Justice Assistance, Uniform Crime Reporting Program, 2008b), 16.

30 Warren, 4-5.

31 Moore.

32 Evans, Donald G. (Journal of Community Corrections, Winter 2006), “The Importance of Community Corrections,” in American Probation and Parole Association, Don Evans: The Musings of a Community Corrections Legend, 2008, 133.

33 CSG, 10-11.

34 Solomon, 1,26.

35 Warren, 4.

36 Warren, 27.

37 Carmichael, 17.

38 Solomon, Amy L., et al., “Putting Public Safety First – 13 Parole Supervision Strategies to Enhance Reentry Outcomes” (The Urban Institute, December 2008), 9, 40.

39 Center for Excellence in Family Studies, “Looking Beyond the Prison Gate: New Directions in Prisoner Reentry” (Wisconsin Family Impact Seminar, January 2008), 15.

40 Warren, 27.

41 Planning and Policy Advisory Committee (PPAC), “Critical Issues: Planning Priorities for the Wisconsin Court System, Fiscal Years 2006-2007 and 2007-2008,” 2006, 13-15.

42 Warren, 43.

43 Warren, xi.

44 Semmann, 40.

45 Dipko, John, email to author, March 23, 2009.

46 CSG, 7.

47 2009-11 Proposed Budget, 295.

48 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (MJS) editorial, “Being Smarter About Who Goes to Prison,” April 18, 2009.

49 Mitchell, George, “Privatizing Parole and Probation in Wisconsin: The Path to Fewer Prisons” (Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, 1999), 17-18.

50 Mitchell, 12.

51 Solomon, 36.

52 Solomon, 37.

53 PLNDP, 31.

54 Segal, 8-13.

55 Barbary, Victoria, “Reducing Re-offending: Creating the Right Framework” (New Local Government Network, London, June 2007), 3.

56 Carmichael, 8.

57 CSG, 9.

58 MJS Editorial.

59 CSG, 9-11.

60 Denckla, Derek & Berman, Greg, “Rethinking the Revolving Door: A Look at Mental Illness in the Courts” (Center for Court Innovation, 2001), 1-4.

61 Wade, Kate, et al., “An Evaluation: Inmate Mental Health Care” (Legislative Audit Bureau, March 2009), 1-84.

62 Wade 90-91.

63 Wade, 85.

64 CSG, 5.

65 PLNDP, 10, 46.

66 CSG, 6.

67 PLNDP, 22, 46.

68 CSG, 5-7.

69 PLNDP, 80.

70 Barbary, 4.

71 Wade, 94-96.

72 Segal, Geoffrey F., “The Extent, History, and Role of Private Companies in the Delivery of Correctional Services in the United States” (Reason Public Policy Institute, 2002), 9-10, 17.

73 Austin, James & Coventry, Garry, “Emerging Issues on Privatized Prisons” (Bureau of Justice Assistance 2001), x.

74 Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance, “Public and Private Benefits in Wisconsin,” The Wisconsin Taxpayer 75:9 (September 2007), 1-2.

75 Carmichael, Appendix XIII.

76 Marshall, Terry, conversation with author,

Feb. 19, 2009.

77 Evans, Donald G. (Corrections Today, July 2005), “International Halfway House Colloquium Reveals Similar Worldwide Challenges,” in American Probation and Parole Association, Don Evans: The Musings of a Community Corrections Legend, 2008, 207.

78 Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, “Expansion of Community Alternative to Revocation (DOC – Adult Corrections),” May 2005, 2.

79 Marshall conversation, Feb. 19, 2009.

80 Schloss, Christine S. & Alarid, Leanne F., “Standards in the Privatization of Probation Services” (Criminal Justice Review, September 2007), 233-234.

81 Anderson, Bob, phone conversation with author, Feb. 20, 2009.

82 Evans 1993, 25.

83 CBI, “Getting Back on the Straight and Narrow,” April 2008, 3-4.

84 Ministry of Justice (MoJ), “Re-offending of Adults: Results from the 2006 Cohort, England and Wales,” September 2008a, 1.

85 National Offender Management Service (NOMS), “National Commissioning Plan 2007/2008: Commissioning Framework,” January 2007a, 2-5.

86 Aldridge, Nick, et al., “Returning to Its Roots? A New Role for the Third Sector in Probation,” September 2006, 13.

87 Aldridge, 14-18.

88 Offender Services Partnership website, available at http://www.offenderservicespartnership.co.uk.

89 Ministry of Justice (MoJ), “Working in Partnership to Reduce Reoffending and Make Communities Safer,” October 2008b, 10.

90 MoJ, 1.

91 CBI, 7,24.

92 NOMS 2007a, 4-5, 22.