Vol. 24, No. 1

Executive Summary

It has been 10 years since Wisconsin overhauled an old set of rules for state teacher licensure (PI 3 and PI 4) and replaced it with a new set called PI 34. At the time of its approval in 2000, PI 34 was warmly welcomed by state leaders and legislators from both sides of the aisle. It was praised as a way to create a new generation of Wisconsin teachers.

The purpose of this report is to assess PI 34 in an effort to learn whether it has made good on these high expectations.

The underlying issue in this assessment has to do with occupational licensure. Why is it widespread in many states including Wisconsin? There are two viewpoints. The first is that consumers don’t have enough information to make judgments regarding the purchase of services from members of certain occupations. Licensure, according to this view, serves as a means to protect consumers from fraud and malpractice.

The second argument is made by economists. It opposes the first. Prominent economists claim that licensure benefits members of various occupations more than it benefits consumers. It does so by limiting access to the occupations in question, thus reducing competition. Those seeking protection from barriers of this sort believe that the various regulations will eventually enhance their incomes. The costs to consumers include reduced competition and restricted consumer choice.

We undertook this study to assess PI 34 in light of this underlying issue: Upon examination, does PI 34 provide substantial protection for consumers? That is, does it serve the public’s interest, and particularly the interests of parents, in quality education? Or does PI 34 protect the producers of education in Wisconsin? In an effort to find out, we traced the history of teacher licensure in Wisconsin, conducted focus group interviews with Wisconsin school principals, and analyzed the relevant state statutes and administrative codes. Our main finding is that PI 34 serves primarily to protect and advance the interests of the producers.

While teacher licensure today is dominated by state law and state officials, it has not always been that way. For much of its early history, certification in Wisconsin was a local affair, operating within arm’s reach of local parents. Gradually, however, superintendents and counties lost power over teacher licensure, giving in to incessant pressure from partisans of centralized, state-level authority. By the end of the 20th century, teacher licensure was no longer a local affair. It had evolved into a system nearly completely controlled by the producers of public education. These included Department of Public Instruction (DPI) bureaucrats, professors of education in the state’s 33 colleges and universities, and the leaders of the Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC).

State-level control over teacher licensure today is firmly established by state statute and state regulatory code specified in Chapters 115 and 118 of state statute and PI 34 of state code. PI 34, adopted in 2000, has some features that benefit the public, including its emphasis on standards-based teacher training and its requirement that all candidates for licensure must take a content-knowledge test (Praxis II). Still, its improvements over the state’s earlier rules (embodied in PI 3 and PI 4) are marginal.

PI 34’s weaknesses far outweigh its strengths. The weaknesses include the following:

• PI 34 undervalues the importance of subject-matter knowledge in initial training programs for teachers and in teachers’ professional development activity.

• PI 34 imposes an overwhelming regulatory system—dwarfing, for example, the regulatory system governing licensure for medical doctors.

• PI 34 rules for licensure renewal fail to ensure that renewal will depend on demonstrated competence and professional growth. These rules create incentives for pro forma compliance, cronyism, and fraud.

• PI 34 sets up high barriers (a single, proprietary avenue) for entrance into teaching. It makes licensure conditional on completion of approved training programs requiring, normally, at least two years of full-time enrollment in education coursework. Many highly trained professionals contemplating career changes are deterred by these requirements from becoming teachers, despite demand for their services.

• PI 34 has no built-in measures for linking teacher licensure to teacher competence. Wisconsin has no evidence that any incompetent teacher has ever been denied licensure renewal.

• PI 34 enables education producers (WEAC and the DPI) to dominate the licensure system. In this system, parents and students are marginalized.

• PI 34 is particularly onerous for educators in large urban districts like Milwaukee, where producing academic gains is a challenging problem, and school principals, struggling to hire competent teachers, would benefit greatly from a flexible licensure system.

Under the current licensure rules, all Wisconsin teachers, competent or not, are protected. Either Wisconsin has invented the perfect teacher training and licensure renewal program, or incompetent teachers are being protected by the current system. Wisconsin’s system of teacher licensure as set forth in Chapters 115 and 118 and PI 34, is operated on behalf of the producers—the DPI, faculty in schools of education, and WEAC—at the expense of the consumers of public education, particularly parents and schoolchildren.

Introduction

It has been 10 years since Wisconsin overhauled an old set of rules for state teacher licensure (PI 3 and PI 4) and replaced it with a new set called PI 34. At the time of its approval in 2000, PI 34 was warmly welcomed by state leaders and legislators from both sides of the aisle. It was praised as a way to create a new generation of Wisconsin teachers. Alan Borsuk1 reported in an article in 2000 that, despite some grumbling here and there, faculties in schools of education, school administrators, and school board members all supported the changes. Borsuk noted that John Benson, state superintendent at the time, said that the new system would “elevate the teaching profession.” The same story quoted Linda Darling-Hammond, a Stanford Professor and international rock star in the world of teacher training, in a similar vein:

I’m pretty impressed with what’s going on in Wisconsin. I’ve always been impressed with what’s going on in Wisconsin. The new standards and requirements actually take Wisconsin to a whole new level in terms of leading the field in what teachers will know and be able to do and be continually supported in.

–JS Online Archives February 29, 2000

The purpose of this report is to assess PI 34 in an effort to learn whether it can make good on these high expectations.

What Is at Stake?

Assessing the status of teacher licensure in Wisconsin is no dry, inconsequential exercise. In efforts to get policies and practice for teacher licensure right, much is at stake. That is because Wisconsin has embarked on its latest changes in regulatory policy from a very low point. More bad policy now would have the potential to cause serious damage to a system that is already weak.

Teacher training in Wisconsin has been excoriated in national studies. The best example is the 2009 State Teacher Policy Yearbook published by the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ).2 This report, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Joyce Foundation, is widely distributed and highly respected. It gives Wisconsin a grade of “D” for its policies related to producing and maintaining teacher quality. Table 1 provides a summary of its evaluations on five criteria.

Table 1: NCQT Area Grades for Wisconsin

Area Grade

1. Delivering Well Prepared Teachers D-

2. Expanding the Teaching Pool D-

3. Identifying Effective Teachers D-

4. Retaining Effective Teachers C

5. Exiting Ineffective Teachers D

It is worth quoting the 2009 NCTQ Report3 verbatim regarding its assessment of how Wisconsin prepares teachers. The report says:

Wisconsin’s policies supporting the delivery of well-prepared teachers are sorely lacking. The state requires teacher candidates to pass a basic skills test prior to program admission, but it does not ensure that elementary teachers are provided with a broad liberal arts education. Elementary teacher preparation programs are not required to address the science of reading or provide mathematics content specifically geared to the needs of elementary teachers. The state does not require elementary candidates to pass a test of the science of reading or a rigorous mathematics assessment. Wisconsin also does not sufficiently prepare middle school teachers to teach appropriate grade-level content, and the state allows middle school teachers to teach on a generalist 1-8 license. The state also does not ensure that special education teachers are adequately prepared to teach content-area subject matter, nor does it require all new teachers to pass a pedagogy test to attain licensure. Unfortunately, the state does not hold preparation programs accountable for the quality of teachers they produce, but it has retained full authority over its program approval process. Further, Wisconsin lacks any policy that ensures efficient preparation of teacher candidates in terms of the professional coursework that may be required.

NCQT is equally hard on Wisconsin regarding its efforts to identify effective teachers. It reports:

Wisconsin’s efforts to identify effective teachers are sorely lacking. The state only has two of the three necessary elements for the development of a student- and teacher-level longitudinal data system, and Wisconsin’s requirements regarding teacher evaluations are too weak to ensure the use of subjective and objective measures such as standardized tests as evidence of student learning. Wisconsin also fails to require multiple evaluations for new teachers or annual evaluations for non-probationary teachers. In addition, the probationary period for new teachers in Wisconsin is just three years, and the state does not require any meaningful process to evaluate cumulative effectiveness in the classroom before teachers are awarded tenure. Wisconsin is on the right track when it comes to basing its licensure requirements on evidence of teacher effectiveness; however, it reports little school-level data that can help support the equitable distribution of teacher talent.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly for the purpose of this report, the NCQT is highly critical of Wisconsin’s efforts to remove ineffective teachers from the classroom. It reports:

Wisconsin issues renewable emergency permits, allowing teachers who have not passed licensing tests to teach for more than one year. The state also fails to articulate a policy regarding teachers who receive unsatisfactory evaluations. Although Wisconsin commendably only allows a single appeal for tenured teachers who are terminated for poor performance, the state fails to distinguish due process rights for teachers dismissed for ineffective performance from those facing license revocation for dereliction of duty or felony and/or morality violations.

How did Wisconsin put itself in the position described in the NCQT evaluation? Will new policies embodied in PI 34 bring about reform, as Darling-Hammond and others have claimed? To pursue these questions, we turn first to a brief look at an underlying issue: the logic of occupational licensure, as viewed from two perspectives.

Two Perspectives on Occupational Licensure

In the United States, occupational licensure operates nearly everywhere. It applies, normally, to doctors, lawyers, teachers, and accountants. In Wisconsin, it also applies to bait dealers, cheese graders, clam shellers, ginseng dealers, fishing guides, tattooists, and taxidermists. The main argument for occupational licensing is that consumers don’t have enough information to make judgments regarding the purchase of services from members of certain occupations. Licensure, according to this view, serves to protect consumers from fraud and malpractice.

One might object that in the absence of licensure consumers would not be entirely without information about the goods and services they wish to purchase. Producers have many ways to communicate information about the value of the goods and services they offer. They make representations in advertising—sometimes reliable and sometimes not. They offer warranties, guarantees, and generous return policies. Some producers (home builders, for example) do not receive final payment until final inspection is completed by the consumer. And producers who fail to protect their customers are likely to be exposed by rival producers through advertising, product comparisons, and so forth.

But state governments generally do not regard these market-based forms of protection as sufficient. They seek additional protection through licensure. In this matter, Wisconsin is notably aggressive. It requires 117 occupational licenses.4 Only California, Connecticut, Arkansas, Maine, and Michigan require more licenses. Wisconsin also exceeds most other states in the percentage of workers covered by licensing. More than 24 percent of Wisconsin’s workers hold occupational licenses. The percentage is higher in only six states: Arkansas (28.56 percent), California (30.36 percent), Connecticut (30.08 percent), Illinois (27.53 percent), Michigan (28.27 percent), and New Hampshire (24.50 percent).

Against this background, economists stand out as skeptics. The skeptical view goes back at least to Adam Smith. He regarded the right to work in the field of one’s choice, without having to face barriers imposed by others, as a fundamental aspect of economic freedom:

The property which every man has is his own labor, as it is the original foundation of all other property, so it is the most sacred and inviolable. The patrimony of a poor man lies in the strength and dexterity of his hands; but to hinder him from employing this strength and dexterity in what manner he thinks proper without injury to his neighbor is a plain violation of this most sacred property. It is a manifest encroachment upon the just liberty both of the workman, and of those who might be disposed to employ him. As it hinders the one from working at what he thinks proper, so it hinders the others from employing whom they think proper. To judge whether he is fit to be employed, may surely be trusted to the discretion of the employers whose interest it so much concerns.5

He objected, accordingly, to guilds that required long apprenticeships, contending that they were devices simply to limit entry into occupations and thus to increase wages.

Far more recently, Nobel laureate Milton Friedman also has objected to occupational licensing. With Simon Kuznets (another Nobel laureate), Friedman wrote Income from Independent Professional Practice (1945), which examined licensing in the medical profession. Later in his career he returned frequently to the topic of licensure. His 1962 classic, Capitalism and Freedom, includes a chapter on occupational licensure, which begins as follows:

The overthrow of the medieval guild system was an indispensable early step in the rise of freedom in the Western world. It was a sign of the triumph of liberal ideas, and widely recognized as such, that by the mid-nineteenth century, in Britain, the United States, and to a lesser extent on the continent of Europe, men could pursue whatever trade or occupation they wished without the by-your-leave of any governmental or quasi-governmental authority. In more recent decades, there has been retrogression, an increasing tendency for particular occupations to be restricted to individuals licensed to practice them by the state.6

The objections voiced by Friedman and other economists generally emphasize Adam Smith’s point that licensure benefits members of various occupations more than it benefits consumers. It does so by limiting access to the occupations in question, thus reducing competition.

Benefitting producers, of course, is never the stated argument for occupational licensing. The arguments used by those seeking licensure emphasize instead the necessity of protecting the public interest. Pressure for establishing licensure requirements invariably comes from members of the occupation to be licensed. Individuals employed in those occupations have strong, concentrated interests at stake. They pay close attention to procedures for determining who is able to enter and remain in the field. Typically, they lobby elected officials to obtain status as a licensed occupation. Then they fight to maintain that status. Once established, occupational licensure seems almost impossible to unwind. Efforts to deregulate occupations are rare in most states and nonexistent in Wisconsin.

It is by no means clear, however, that licensure is necessary as a proxy measure of competence for K-12 teachers. Most parents place a high value on the welfare of their children and, as a result, are deeply concerned about the education their children receive. Their concern is well founded: Teacher quality is the most important factor in improving student learning.7 Sensing this, parents have a strong incentive to seek out information about the kindergarten teacher who may teach their five-year-old child or the algebra teacher who may teach their ninth-grader. The relevant information, moreover, is not so arcane that only technical experts can locate or understand it. School visits, conferences with teachers, and conversations with other parents often yield highly reliable information about how well or how poorly certain teachers teach. Within the education profession, in fact, technical expertise related to teaching is often derided as a poor substitute for experience, intuition, empathy, caring, and other personal qualities—qualities that parents, among other non-experts, would be well qualified to assess.

What does all this have to do with teacher licensure in Wisconsin? A lot. Licensure rests on the assumption that a strong regulatory system is needed to ensure that only competent, effective teachers will be employed in Wisconsin’s classrooms.

It is not necessary, according to this view, even to consider the alternative possibility—that parents and principals entrusted with the task might assess teacher quality very well, given the strong incentives they would have to do so carefully, and given that the information needed to assess teacher quality is neither occult nor inaccessible. To the extent that the alternative possibility has a solid basis in the relevant evidence, Wisconsin’s new, ongoing licensure project is a move in the wrong direction. It will be more likely to promote the interests of teachers and bureaucrats than those of parents and children.

A Brief History of Teacher Licensure in Wisconsin

Licensure Prior to the 20th Century

Scholars who write about the history of state teacher certification and licensure generally present a narrative dominated by progressive ideology. They describe the establishment of state-dominated teacher certification as the inevitable result of enlightened professional practice. They extol the virtues of the state’s role. Here is one example: 8

The basic problem in education is that of getting the best possible teachers for the classrooms. The methods of selecting and licensing teachers in Wisconsin have moved from local authorities to a complete control of certification by the state superintendent. It took 90 years to accomplish this necessary centralization, for the law placing certification into the Department of Public Instruction was not passed until 1939.

This has not always been the dominant view. In colonial America it was common for teachers to be approved by ministers, who were primarily concerned about the moral character of those entrusted with the education of the community’s young people. Over the course of the 19th century, the authority for licensing teachers passed from religious to civil authorities. Early on, however, licensure remained a local affair, operating within arm’s reach of parents. In the 1840s, it was common for most U.S. teachers to receive their teaching certificate from local officials, based on their performance on an examination. Under the first Wisconsin school code, the town superintendent examined and licensed teachers, guided by no state regulations of any kind. This examination often consisted of a few questions posed orally by a member of the school board. Often these officials were trying to ascertain whether the candidate knew as much about geography and arithmetic as did the older children he or she would be teaching. Later, longer and more detailed examinations were developed.

In 1861, Wisconsin created the office of county superintendent. County superintendents were authorized to grant certification in 1862. Examinations were to be administered by the county superintendent in the areas of moral character, learning, and ability to teach. Three grades of certification were created: first grade, second grade, and third grade. In 1868 Wisconsin created a state board of examiners with power to issue certificates good in any Wisconsin county. Eventually this form of certificate was extended to five years; and eventually teachers could earn lifetime certificates.

The move toward lifetime certificates probably had something to do with the labor-intensive nature of examining teachers individually. Donnelly9 provides a glimpse of the situation in Milwaukee around the time of the Civil War. He reports that the superintendent in the Milwaukee Public Schools spent most of his time examining and certifying teachers as well as examining classes of students. “Yearly examinations of teachers,” he reports, “had been required until the time of Mr. Pomeroy’s administration, and having himself been required to go through this humiliating annual test, he soon induced the school board to abandon it. Since his time, a teacher’s certificate is required but once.”

Like many other states, Wisconsin had essentially two tracks for teacher certification, one for the cities and one for rural areas. Teachers in urban areas often received their training in normal schools. Normal schools were teacher-training institutions that provided what was essentially a high school education for prospective teachers. These normal schools eventually evolved into colleges of education and into Wisconsin state universities. By 1897, 28 states certified teachers on the basis of graduation from a normal school or university, without further examination.

In 1866, Wisconsin’s Legislature authorized the Wisconsin Board of Regents of Normal Schools to establish normal schools in different parts of the state. The first state normal was established at Platteville in 1867; the second was established at Whitewater in 1868. Others soon followed: Oshkosh, 1871; River Falls, 1875; Milwaukee, 1885; Stevens Point, 1894; Superior, 1896; La Crosse, 1909; and Eau Claire, 1916. Until 1925 these institutions were called normal schools, and the training programs they offered were usually two years in length. In 1925, the Legislature changed the name to Teachers Colleges and extended programs of study to four years; it also authorized the new Teachers Colleges to grant the degree of Bachelor of Education.

Other institutions also offered training programs, especially in rural areas. Rural schools have always faced special difficulties in attracting good teachers. In response to this problem, teacher institutes grew up in several rural areas after the Civil War. They were developed to provide formal training for prospective teachers who held third-grade certificates and had six or fewer weeks of formal training in pedagogy. Those who desired higher certification, for teaching in elementary or secondary schools, attended the state normal schools. Most institutes were held as summer programs, lasting from a few days to a month or more. They were mainly locally controlled institutions, highly responsive to local concerns, and they were generally self-supporting and inexpensive.

Licensure Early in the 20th Century

The existence of two routes to teacher certification, rural and urban, stirred up tension among some educators. The vast majority of country-school teachers (teachers in one-room schoolhouses) either had no training at all or entered their careers by means of teacher institutes. According to Angus, professional educators at normal schools despised the teacher institutes. This was because “they didn’t control [the institutes] and were seldom invited to participate [in institute training programs], but also [because institutes] threatened the image of professionalism that the educators were attempting to promote for teaching.”10 In this effort, the professionals were clearly up against a different, well-established view. Throughout the 19th century, Angus continues,

The “citizen,’” not the professional educator, [had been] in control of the certification of teachers. Although the period saw the beginnings of formal training schemes of various sorts, as well as their recognition in certification practices, the idea promoted by career educators that it was essential for all teachers to be trained in such programs made small inroads. This was partly because of the relative power of local communities over state authorities in the management and regulation of schools, but also because of a deeply rooted belief that teaching was something that most adults could do.11

The tide turned in the first half of the 20th century; progressive educators triumphed in their struggle to control teacher licensure. Early in the century, Wisconsin began, via state legislation, to create a hierarchical, bureaucratic licensure system. Local authorities would no longer decide who should be licensed teach in their schools.

The regulatory regime developed steadily. In 1909 a new certification rule required prospective teachers to attend a professional school for at least six weeks as a prerequisite for taking all examinations. In 1930, this requirement was increased to two years beyond the eighth grade. In 1939, all authority over teacher certification was given to the state superintendent. Subsequently, nearly all certificates to teach were issued on the basis of a candidate’s graduation from a Wisconsin state teachers college, or a county normal school, Stout Institute, the University of Wisconsin, and other accredited colleges. To obtain accreditation, these institutions had to meet requirements approved by the state superintendent. From that time on, the number of formal requirements for teacher certification increased, the number of specialized certifications increased, and the use of examinations plummeted.

Licensure After 1960

In 1960, Wisconsin adopted Chapters PI 3 and PI 4 of the Wisconsin Administrative Code for the Department of Public Instruction. PI 3 and PI 4 established a new set of regulations to govern teacher certification and licensure. The two chapters run to 64 pages. They comprise more than 24 subchapters, each of which is further developed with subpoints. In total, PI 3 and PI 4 included more than 2,000 separate subchapters and subpoints. PI 3 and PI 4 cast a wide net. General requirements (PI 3.05) for a teaching license included university or field-based coursework specified by 15 main code points shown in Appendix I.

In the 1990s, criticism of PI 3 and PI 4 emerged. A report by Schug and Western,12 for example, argued that the regulatory scheme created by PI 3 and PI 4 had three main flaws. The regulations were costly. The authors estimated that Wisconsin taxpayers spent (at the time of publication) $62,425,968 to produce each year’s supply of new teachers. The regulations were outmoded. The regulatory culture of the licensure and training system fostered compliance, not innovation. And the regulations were unreliable. The rules of PI 3 and PI 4 specified program inputs, not results. No performance standards — referenced to the attainment of program objectives or K-12 learning outcomes — were included.

By the end of the 20th century, as evidenced by PI 3 and PI 4, teacher licensure in Wisconsin was completely under the control of the producers of public education. In command were the DPI and the departments and schools of education in state colleges and universities. The Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC) also emerged as an important player. In 1973, for example, WEAC reported that its lobbying led to the passage of the 13 Educational Standards bill, establishing that all teachers must be certified by the DPI, that every school district must provide kindergarten, special education, guidance counselors, and other measures. By the 1970s, it was clear that any important changes in the rules for teacher licensure would have to pass WEAC muster.

In 1994, State Superintendent John Benson appointed the Restructuring Teacher Education and Licensure in Wisconsin Task Force and charged it to develop a new structure for teacher preparation and certification. The Task Force recommendations were reported in April 1995. Hearings and revisions followed.

Eventually, with much fanfare from legislators, the governor, the DPI, and nationally respected teacher educators, the state legislature passed PI 34 in 2000, and new administrative rules were developed. PI 34 replaced PI 4 (program approvals for colleges and universities) in 2000 and PI 3 (license requirements) in 2004.

With these new acts, Wisconsin’s state superintendent and legislators claimed that they had established a system of regulations that would spawn a new generation of Wisconsin teachers. They were right, of course. The question is, what sort of generation of teachers did they have in mind? Was it one that parents would find to be in their best interests and the best interests of their children? Or was it one that would protect the interests of the producers —the faculties of schools of education, DPI bureaucrats, and incompetent teachers?

Teacher Licensure in Wisconsin Today: The Rules

Rules in Wisconsin Statutes

Teacher certification and licensure are regulated by state statute and state regulatory code. The rules for teacher licensure are presented in Chapter 115 and Chapter 118 of state statutes and in PI 34 of state code. We will describe each, focusing especially on PI 34, the most inclusive statement of Wisconsin’s licensure rules.

Chapter 115 primarily describes processes for license revocation, grants for national teacher certification and master educator licensure, and the professional standards council for teachers. Chapter 118 has more to say regarding teaching licensure. It specifies, for example, that anyone who wants to teach in a Wisconsin public school must obtain a Wisconsin teaching license:

Except as provided in s. 118.40 (8) (b) 2., any person seeking to teach in a public school, including a charter school, or in a school or institution operated by a county or the state, shall first procure a license or permit from the department.

Chapter 118 provides that a teacher is not to be issued a license or have a license renewed if he or she is delinquent in paying taxes or in paying for child support. A person may not be issued a license or have one renewed if he or she is a convicted felon. Chapter 118 also includes the statutory requirements—specifying content that must be included in a teacher training program (these requirements also appear in PI 34). For example, prospective teachers preparing to teach courses in economics, social studies, or agriculture must have studied “cooperative marketing and consumers’ cooperatives,” conflict resolution, and minority group relations, including “instruction in the history, culture and tribal sovereignty of the federally recognized American Indian tribes and bands located in this state.” Finally, Chapter 118, beginning with 118.23, lays out the rules for teacher tenure. This section explains that beginning teachers have three years of probation after which “their employment shall be permanent.” It also specifies the conditions under which a tenured teacher may be discharged:

No teacher who has become permanently employed under this section may be refused employment, dismissed, removed or discharged, except for inefficiency or immorality, for willful and persistent violation of reasonable regulations of the governing body of the school system or school or for other good cause, upon written charges based on fact preferred by the governing body or other proper officer of the school system or school in which the teacher is employed.

Rules in Wisconsin Administrative Code: PI 34

What does it take to produce a licensed teacher in Wisconsin? It takes a great deal, if state rules are used as the metric. Reading PI 34 is a daunting task. It includes 26 pages of rules. It begins ominously by stating 63 definitions. It has 13 subchapters with a total of 884 separate code points and subpoints.

How dense and far-reaching is PI 34? We can get a feeling for that question by contrasting the state’s rules for teacher training and licensure with the rules for licensing medical doctors. Chapter Med 1of the Wisconsin Administrative Code states the rules that govern applications and examinations for a license to practice medicine or surgery. Table 2 provides a simple comparison of these two laws.

Table 2: A Comparison of Two Wisconsin State Codes

| Chapter Med 1: License to Practice Medicine and Surgery | Chapter PI 34: Teacher Education Program Approval and Licenses | |

| Purpose | Governs the license to practice medicine and surgery in Wisconsin. | Describes the state’s requirements for teacher education programs and the licensing of public school teachers. |

| Pages | 3 | 26 |

| Definitions in Subchapter 1 | 3 | 63 |

| Subchapters | 1 | 13 |

Teacher Education Standards

The primary difference between these two regulatory schemes—and the explanation for why PI 34 is so much longer—is that Chapter Med 1 requires that licensed physicians be graduates of approved medical schools. However, Med 1 is not prescriptive about how these medical schools train doctors. That question is left for the experts in the field to work out on their own.

PI 34, by contrast, specifies in excruciating detail how a school of education must prepare a teacher in Wisconsin. The specifications begin with a set of core principles or teacher standards. To be licensed to teach in Wisconsin, a prospective teacher must complete a teacher education program approved by the state and be proficient according to the following ten standards:

1. The teacher understands the central concepts, tools of inquiry, and structures of the disciplines he or she teaches and can create learning experiences that make these aspects of subject matter meaningful for pupils.

2. The teacher understands how children with broad ranges of ability learn and provides instruction that supports their intellectual, social, and personal development.

3. The teacher understands how pupils differ in their approaches to learning and the barriers that impede learning and can adapt instruction to meet the diverse needs of pupils, including those with disabilities and exceptionalities.

4. The teacher understands and uses a variety of instructional strategies, including the use of technology to encourage children’s development of critical thinking, problem solving, and performance skills.

5. The teacher uses an understanding of individual and group motivation and behavior to create a learning environment that encourages positive social interaction, active engagement in learning, and self-motivation.

6. The teacher uses effective verbal and nonverbal communication techniques as well as instructional media and technology to foster active inquiry, collaboration, and supportive interaction in the classroom.

7. The teacher organizes and plans systematic instruction based upon knowledge of subject matter, pupils, the community, and curriculum goals.

8. The teacher understands and uses formal and informal assessment strategies to evaluate and ensure the continuous intellectual, social, and physical development of the pupil.

9. The teacher is a reflective practitioner who continually evaluates the effect of his or her choices and actions on pupils, parents, professionals in the learning community and others, and who actively seeks out opportunities to grow professionally.

10. The teacher fosters relationships with school colleagues, parents, and agencies in the larger community to support pupil learning and wellbeing and who acts with integrity, fairness and in an ethical manner.

These 10 standards are based largely on a set of national standards produced early in the 1990s by the Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC). Peter Burke, of the Wisconsin DPI (Burke is widely regarded as a primary architect of PI 34), and Mary Deitz, of Alverno College, served on the drafting committee. The INTASC standards gained widespread approval early on, largely because they are written in terms of expected performance. Up to that point, most documents regarding the training of teachers amounted to long lists of program inputs, with no emphasis on outcomes. This was one of the problems with the earlier PI 3 and PI 4 rules in Wisconsin.

Teacher Education Program Standards

PI 34 goes on to specify what is to be included in an approved teacher education program. These regulations specify the organization of a school, college, or department of education, the qualifications of faculty members, facilities and student services to be provided, student recruitment and admission procedures, and what is to be included at minimum in a teacher education “conceptual framework.” Here is a brief overview of each section:

Provide organization and support for teacher education. This section specifies that each institution must have an institutional structure such as a school or department that is charged with the responsibility to manage a teacher training program. The rules call for policies regarding selection, promotion, and tenure of faculty, teaching loads, faculty development opportunities, as well as facilities, equipment, and budgets.

Recruit a diverse faculty. This section states that each institution is required to recruit, hire, and retain a diverse teacher education faculty.

Have adequate facilities, technology and support. This section calls for the institution to provide adequate classroom, laboratory, office space, and workspace, equipped with current technology, equipment, and supplies.

Provide student services. This section calls for the institution to provide advising resources and materials to students. It also specifies rules for keeping student records. Each student is required to have a portfolio of evidence that the 10 standards [see PI 34.13 (3) (b)] have been met. Finally, the institution is required to report how well its graduates do in finding teaching jobs and in moving from one stage of certification to another.

Provide student recruitment, admission and retention. This section calls for the institution to have a plan and adequate resources to attract a diverse student body.

Provide a conceptual framework. This section requires each institution to be “well defined, articulated, and defensible.” It specifies that the framework must incorporate a performance-based professional education program based on the 10 standards. It calls for additional assessments in such areas as communication skills, human relations, and content knowledge. It requires that potential teachers must earn passing scores on standardized tests approved by the state superintendent. In addition, the conceptual framework must address pedagogical knowledge and teaching practice.

The conceptual framework must also incorporate statutory requirements:

• Cooperative marketing and consumer cooperatives for licenses in economics, social studies, or agriculture.

• Environmental education including the conservation of natural resources for licenses in agriculture, early childhood, middle childhood to early adolescent, science, and social studies.

• Minority group relations for all licenses, including content on the history, culture, and sovereignty of American Indian tribes in Wisconsin.

The conceptual framework states that education for conflict resolution is required of all teachers. This includes topics you might expect, such as how to resolve conflicts between students and teachers and how to deal with school violence. But the conflict resolution requirement also specifies that student teachers should teach full days for a full school (not college) semester. It states that phonics must be included at the elementary education level in reading and language arts methods courses. And it further describes procedures for assessing and providing education for children with disabilities.

The conceptual framework concludes with a long list of rules regarding student teaching. It specifies the rules governing a pre-student teaching, student teaching, and other clinical experiences. It calls for supervision, assessments and two written evaluations of each student doing a “pre-student teaching” experience, based upon observations, teacher evaluations, and a student portfolio. It requires each teacher training institution to provide at least four classroom supervisions and to prepare at least four written evaluations of each student teacher. It further specifies the rules institutions should follow for approving “cooperating teachers”—classroom teachers who work with student teachers.

Licensure Stages

PI 34 is regarded by some as being innovative because it provides for stages of licensing. Until recently, teachers obtained an initial teaching license and followed procedures to renew the same license. There was no sense of hierarchy. This changed with the approval of PI 34. Here is how it works.

The first stage is called the initial educator license. An individual obtains this license by completing a DPI-approved teacher training program at a state college or university. This license is issued for five years and is non-renewable. Assume that a newly licensed teacher is able to find a teaching position. PI 34 requires that teacher to set up an initial-educator team to review his or her professional progress. The team is to include another teacher, a school administrator, and a representative from a college or university. The initial educator is to prepare a Professional Development Plan (PDP) that is to be approved by the initial educator team. The plan is supposed to be congruent with the state’s teacher standards, and it is supposed to identify professional development goals and activities along a timeline.

It is supposed to specify how the initial educator will provide evidence of working well with others and “indicators of growth.”

If the initial educator team approves the documentation provided by the initial educator within three to five years, the teacher is approved to move to the next licensure stage—i.e., to seek the professional educator license.

The professional educator license is almost identical to the initial educator license. The process for renewing this license calls for the professional educator to set up a professional development team made of at least three peer-approved and licensed classroom teachers. The professional educator follows the same procedure as the initial educator to renew his or her teaching license. The procedure must provide evidence that the assessment plan resulted in the improvement of the teacher’s professional knowledge and somehow affected student learning.

The final stage of certification is the master educator license. This is an optional license and is issued for 10 years. A teacher who has earned national board certification is also granted a master educator license (see http://www.nbpts.org/).

The master educator license requires:

• Completion of a master’s degree.

• Five years of successful professional experience in education with at least one cycle at the professional educator level, or while holding a five−year license or a life license issued prior to July 1, 2004.

• Evidence of contributions to the profession.

• Evidence of improved pupil learning.

The candidate for a master teacher license is judged by an assessment team made up of three educators who have the same or similar job responsibilities; the team may also include a school board member. The candidate for this license must submit a formal assessment, which may include interviews, objective examinations, portfolios, or other methods of analysis and appraisal. The candidate must also submit a demonstration of exemplary classroom performance through video or through classroom observation by the team.

Teachers who were licensed under the old rules were not required to move into the new system. They were “grandfathered” into the new rules. Only teachers completing programs beginning in 2004 are involved. Thus, the implementation of the licensure stages to all teachers will take decades.

Teaching Categories and Levels

The next major section of PI 34 specifies levels of certification, scrapping the previous designations. The new categories are:

• Early childhood, which refers to licensure for working with children from birth through 8 years old.

• Early childhood through middle childhood, which refers to licensure for working with children from birth through 11 years old.

• Middle childhood through early adolescence, which refers to licensure for working with children 6 through 12 or 13 years old.

• Early adolescence through adolescence, which refers to licensure for working with young people 10 through 21 years old.

What is required in professional training for licensure in these categories? We will describe two popular categories to give the reader a sense of what is involved. The license for early childhood through middle childhood is popular because it resembles the old elementary teacher license while extending the range into the middle-school grades. School principals like this license because it gives them some flexibility in assigning teachers to grade levels. To become licensed as an early childhood through middle childhood teacher, the candidate must complete an approved program at a state college or university at this age level. The approved program is required to include the code points specified under the teacher standards and the program standards described earlier, including completion of a content-knowledge test. The teacher candidate must also complete a minor. PI 34 provides a long list of possible choices for minors including English, mathematics, science, and social studies, as well as agriculture, art, business education, and dance. Completing such a program will allow an individual to be licensed to teach in any category, except a foreign language, in a self-contained classroom. It would also allow an individual to teach in a departmentalized middle school in all of the following areas: language arts, mathematics, science, social studies, health.

Early adolescence through adolescence is another popular licensure category. It essentially enables a teacher candidate who wants to teach secondary school to be certified to teach at the middle school and high school levels. For people seeking licensure in this range, social studies is often a popular teaching area. To become licensed as an early adolescence through adolescence teacher of social studies, an individual must complete an approved program at a state college or university at this age level. The approved program must address the code points specified under the teacher standards and the program standards described earlier, including completion of a content-knowledge test. Individuals must also complete a social studies program major. The subjects for majors are the following: geography, history, political science and citizenship, economics, psychology, sociology.

An area of concentration, rather than a major, is required to teach junior and senior high school courses in such subjects as economics and political science.

Licensure Revocation and Denial

We turn here to the section of PI 34 that provides standards for license revocation, reinstatement, and denial. The section states the following:

The state superintendent may revoke any license issued by the department for incompetency or immoral conduct on the part of the licensee. In making a decision to revoke a license, the state superintendent shall adhere to the following standards:

1. A license may be revoked for immoral conduct if the state superintendent establishes by a preponderance of the evidence that the person engaged in immoral conduct.

2. A license may be revoked for incompetency if the state superintendent establishes by a preponderance of the evidence that the incompetency endangers the health, welfare, safety or education of any pupil.

The licensure revocation and denial section goes on to describe an elaborate process for the handling of complaints against licensed teachers, specifying how complaints are to be investigated, setting timelines, defining probable cause, setting rules for how to hold hearings, and so forth.

Last, the state superintendent may deny a teaching license to a person who has not met the requirements for licensure as specified in PI 34 and other relevant state statutes. The state superintendent may also deny a teaching license to a person who was denied or had a license revoked in another state.

Professional Standards Council

The final section of PI 34 explains the formation of a Professional Standards Council for teachers within the Department of Public Instruction (see http://dpi.wi.gov/tepdl/pschome.html). This council consists of 19 members.

This is the Council’s task:

• Advise the state superintendent on standards for the licensure of teachers, including initial licensure and maintenance and renewal of licenses, to ensure the effective teaching of a relevant curriculum in Wisconsin schools.

• Propose to the state superintendent standards for evaluating and approving teacher education programs, including continuing education programs.

• Provide to the state superintendent an ongoing assessment of the complexities of teaching and the status of the teaching profession in this state.

• Propose to the state superintendent policies and practices for school boards and state and local teacher organizations to use in developing effective teaching.

• Propose to the state superintendent standards and procedures for revoking a teaching license.

• Propose to the state superintendent ways to recognize excellence in teaching, including the assessment administered by the national board for professional teaching standards and master educator licensure, and to assist teachers to achieve excellence in teaching.

• Propose to the state superintendent effective peer assistance and peer mentoring models, including evaluation systems, and alternative teacher dismissal procedures for consideration by school boards and labor organizations.

• Review and make recommendations regarding administrative rules proposed by the department that relate to teacher preparation, licensure and regulation.

• Propose to the state superintendent alternative procedures for the preparation and licensure of teachers.

• Report annually to the standing committees in each house of the Legislature that deal with education matters on the activities and effectiveness of the council.

Results from Focus Group Discussions with Wisconsin Principals

We have gone on at some length describing the new regulatory scheme for teacher certification and licensure in Wisconsin in order to disclose its imposing bulk and density. To assess the practical application of the new rules, we conducted focus-group meetings with school principals—five from Milwaukee-area private and charter schools and three from Milwaukee-area public schools. We met with these principals for one and a half hours to discuss issues related to PI 34. In particular, we were interested in how PI 34—licensure rules that three of them are not required to follow—might affect them in their day-to-day efforts to run schools well.

Private and Charter School Principals

Initially, we asked the principals how they go about recruiting teachers, what they look for, and how important state certification is. The principal of a high-performing Milwaukee-area Catholic high school remarked that “Teaching experience is much more important than certification.” Nonetheless, this principal explained that while his school does employ non-certified teachers, including some selected specifically for their professional backgrounds, the school does seek to hire certified teachers.

The principal of a Milwaukee-area charter school that is required to hire state-licensed teachers stated that “Certification has absolutely no bearing on success in the classroom.” Another principal mentioned that his school employs a biomedical engineer as a biology teacher, and that this teacher has been very effective. When this teacher was forced to obtain a teaching license as a requirement for keeping his job, he considered the required process “a waste of time.”

The principal of a high school that participates in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program remarked that he often hires certified teachers as a defensive move in anticipation that the state Legislature will eventually require this of the schools participating in the choice program. He expanded by saying that “I would absolutely not require certification otherwise. … good teaching has nothing to do with certification.” This principal added that one of his worst teachers is a Master Educator certified as such by the state of Wisconsin.

The principal of an inner-city private high school stated that “solid academic background in a content area” is the most important factor in his hiring decisions.

He mentioned that his school has made an effort to hire licensed teachers because the Milwaukee Archdiocese values it and because it is required if the school is to be a host to student teachers from local colleges and universities. Educators at this school are particularly interested in hosting student teachers; they hope to develop the school as a training ground for urban educators.

The principals from non-charter schools explained that, because they are not required to abide by the PI 34 rules, they are able to swiftly and easily remove teachers who are not performing well in the classroom. Each of these principals mentioned that value-added student growth data (i.e., evidence of student learning) is used, in part, to measure the performance of their teachers.

When asked about the strengths of PI 34, and the certification process in general, the principals identified a number of factors. They agreed that certified teachers come to the job understanding the language of education and the principles and practices of professional education. They seemed to mean the certified teachers had a basic knowledge of making lesson plans and what might be expected from students. The principals seemed to think this was particularly important at the primary grade levels. The certification process also keeps teachers going back to school for further education, which the principals valued. One of the principals remarked that PI 34 was an improvement over the previous system in that it wasn’t simply based on how many university credits a teacher earned every few years. This principal added, “I like the spirit of the rules even though I’ve never seen its results put into practice.”

When asked about weaknesses in PI 34, the private school principals mentioned that they didn’t know the law well as they are not required to abide by it. One of them did state that under PI 34 it is extremely difficult to prevent teachers from renewing their teaching license as they work through the Professional Development Plan (PDP) process. He explained that, in his experience, because the teacher under review has developed a relationship with the members of the review committee, they are predisposed to believe the teacher is doing a good job.

When the principals were asked about potential reforms or improvements to the process, one principal suggested that a school or district-based certification process would be much more effective. All of the other principals agreed. They discussed the fact that a one-size-fits-all certification process designed in Madison makes little sense, as teachers who are effective in a suburban environment may not have the skills to be effective in an urban environment. The private school principals mentioned that they would prefer that it be left to the schools to find the best teachers rather than being governed by distant statewide rules. One principal said that “schools are too different for such a blunt instrument.”

Public School Principals

We conducted a second focus group meeting with three principals of Milwaukee-area public schools. They were much more knowledgeable about PI 34 and the procedures it entails. In fact, all of the principals had had experience with the Professional Development Plan (PDP) process and were actively involved in reviewing professional development plans at the time of the interview. Some brought plans along to the interview as points of reference for their comments on the license renewal process.

The public school principals identified a handful of strengths in the new state code. They were pleased with the training sessions for new teachers that their districts conducted; they were pleased, too, with the professional development efforts that went along with these sessions. One principal identified the code’s linkage to the state’s teacher standards as a strength. All the principals commented that “on paper” PI 34 would appear to provide qualified and competent teachers.

The principals were much less impressed with how PI 34 works in practice. The first weakness they identified had to do with the process teachers follow in writing a PDP.

Each one of them mentioned that the PDP process is very weak and requires little effort. One principal mentioned that there is “too much of a fudge factor.” She explained that “Teachers can write down anything they want on their PDP and never have to show evidence of accomplishment.” Another principal added that “At least under the old system [PI 3 and PI 4] the teachers had to actually take some professional development courses.” One principal had written down some comments teachers at her school had written on their PDPs; by reference to these, he questioned the value of statements like “Discuss with colleagues”—asking “What does this mean?” and “Who assures it’s actually happening?”

These principals, experienced in the PDP process, said that no one looks at the activities described in the PDP plans or monitors them. They called the PDP process “ambiguous.” One principal provided the following analogy: “The current process is like asking the patient to diagnose his own illness and then write his own prescription.” In the most revealing and candid portion of the focus group session, each of the principals reported that the process is rife with fraud. Three principals said they knew of examples in which “Teachers are writing the PDPs for other teachers.” More strikingly, two of the principals were familiar with teachers paying review committee members to sign off on their PDP plans. One principal explained it this way: “People are getting paid to sign and write these plans for others. The going rate is about $50 to $75, typically paid with a gift card to avoid detection.”

The principals questioned the effect of PI 34 on hiring high-quality teachers. Each principal had stories of non-certified teachers who excelled at raising student achievement but had to be let go because they were not licensed. Sometimes this was because the teacher had not yet completed all the education requirements mandated by PI 34, including passing the Praxis II exam. Sometimes the teacher was an expert in a specific field but had not gone through a teacher preparation program. One principal said, “I had a wonderful business teacher that was not certified. He was able to motivate and relate to students but we couldn’t keep him. We considered moving him into the administration just to keep him on the job.”

Another principal said, “Two of my highest-performing teachers measured by student growth on test scores were not certified or highly qualified.” The principals agreed that being certified under PI 34 offered no assurance that teachers could motivate, teach, or relate to students.

Each of the principals reported stories of incompetent teachers protected under the current system. One principal put it this way: “What business would put up with incompetent employees? What business would put up with people that come late on a daily basis? I’m forced to employ people that don’t respect their product [education] or customer [students] because they have a license.” One principal told a long story about a teacher who got drunk on a school field trip. Even after pushing students to the floor, locking girls in the bathroom, and snapping towels at students, the teacher was not dismissed. Instead, he was transferred to another school. The union’s justification for not removing this teacher—a teacher this principal told us “should never be around kids”—was that “He was both licensed and highly qualified so he must be a great teacher that made a mistake.”

The principals told us that the current process forces them to “game the system.” They all described special relationships they’ve developed with the human resources people in their districts in order to hire the best applicants for teaching positions. Further, one of the principals described her desire to bring in as many student teachers as possible each year so she could pick the best one to work subsequently at her school. This principal also described an interview process she follows to seek out the best possible teachers. The process is remarkably similar to what one would encounter at a private business: initial interview with tough questions, reference checks with recent employers, and a follow-up interview.

Finally, these principals echoed certain points made by the private school principals. They found it hard to imagine that rule writers in Madison could possibly understand the complexity of teaching—especially in an urban environment. One principal said, “The art of teaching is hard to quantify. I know individuals who are highly qualified on paper but simply bomb out in the classroom.”

In summary, the principals with whom we spoke do not view teacher licensure as providing any assurance that teachers will be effective in the classroom. Each of the principals, to a person, believed that PI 34 was too blunt a policy instrument and couldn’t possibly ensure that a teacher was qualified and right for their school. They felt much more confident in their own ability and judgment to determine which teacher candidates could best serve their school circumstances, their students, and their parents.

Strengths of PI 34

Notwithstanding the principals’ criticisms, PI 34 does seem to have brought about two improvements to Wisconsin’s teacher licensure system. First, the earlier rules for teacher licensure were even more prescriptive than those we see in PI 34. PI 3 and PI 4, for example, listed the actual courses students would need to take. They put forward strictly an input program, with no attention to results. PI 34 does reflect a new effort to shape certification and licensure rules as standards to be met. The teacher training programs in Wisconsin colleges and universities are challenged, accordingly, to devise programs to meet the standards in order to qualify for program approval. This amounts to a step forward.

Second, Wisconsin teachers are now required to take a content-knowledge test. The possibility of a content-knowledge test for teachers had been discussed for many years and was fiercely resisted by the DPI. Gov. Tommy Thompson, however, insisted on the test and asked for little else. As a result, PI 34 requires that individuals who wish to teach must take a content-knowledge test. We know firsthand that the use of these tests has eliminated certain students from programs and, in one case, brought about the elimination of a complete program, albeit a small one.

Weaknesses of PI 34

We identify eight main weaknesses in PI 34:

1. PI 34 amounts to regulatory overkill.

How on earth could the Wisconsin Legislature have imagined that the licensure staff at the DPI (about nine people) could enforce 884 code points and subpoints, which apply to 33 colleges and universities across the state and involve thousands of Wisconsin teachers? There is very little meaningful activity at the DPI to ensure that Wisconsin prepares and retains high-quality teachers of the sort parents want and children need. Instead of streamlining its bureaucratic procedures, PI 34 piles them on, requiring tasks that are next to impossible, in some cases, and simple make-work in others.

2. Wisconsin’s teacher standards fail to distinguish between more important and less important areas of teacher competence.

The 10 standards are presented as being equivalent to one another. There is no sense of priority or logical relationships among them. This is a matter of real consequence, since teachers seeking licensure renewal may choose any two standards from the list to address in their Professional Development Plans—as if all were of equal merit. But obviously the standards are not all of equal merit. They ought to be weighted for their relative importance. Only one standard (standard 1) states that teachers should have a rigorous preparation in academic subjects such as mathematics, science, and history. But other standards on the list address student learning less directly, and some address it not at all. As a result, Wisconsin’s teacher standards seem to marginalize subject-matter knowledge for teachers. It is something a teacher can sidestep in his or her movement toward advanced certification.

3. The system for license renewal lacks teeth.

Everyone in the system knows that the process for recertification is of limited rigor. The incentives are all wrong. Teachers who are initial educators, for example, play an important role in deciding who serves on their review committees. How hard do we think beginning teachers—people who would like to keep their jobs and get their state pensions—wish to be on themselves? It gets worse. What if you are a weak teacher? What sort of individuals would you wish to serve on your review committee? Obviously, you would try to find individuals who will not be too critical of you. Since their livelihood is at stake, to what lengths do you suppose some teachers would go to make sure that they have a favorably disposed review committee? The answer is obvious, of course. They would go a long way. All of this is confirmed by the principals we spoke with. Frankly, things were worse than we thought they might be. The principals said they had firsthand knowledge of teachers paying others to write their Professional Development Plans and paying review committee members to sign off on forms attesting that they had accomplished the objectives stated in these plans.

4. PI 34 creates incentives that encourage teachers and others to “game the system.”

The vagueness of specifications for the preparation of Professional Development Plans makes it easy for teachers to submit highly subjective accounts of their teaching practices and results. No objective measures or outcomes are required. No one monitors events to make sure that actions stated in the Professional Development Plans (“I will take a course in managing achievement data” or “I will observe effective teachers in my school”) are actually completed. It fails at the most basic levels. The reviewers don’t even know for sure if the documents they are reviewing were actually prepared by the teacher who is being reviewed. Opportunities for fraud and deception are widespread.

In this context, teachers who are effective in the classroom should be the most angry and embarrassed participants. PI 34 demeans them by running them through the weak system that shelters those less competent.

And what are the incentives for the members of the review panels? Why would members of a review team ever wish to non-renew the license of a beginning teacher? After all, they would receive no reward for acting as strict enforcers. In fact, being a strict enforcer would cause them problems. Why would a teacher, a school administrator, or a representative from a college or university want to cause a beginning teacher—someone who is probably a decent and courteous individual—to lose his or her job? Why would these reviewers wish to acquire the reputation of being ruthless monsters who ruin the lives of struggling beginners?

Most would not, of course. Here, too, the incentives encourage people to game the system. It may not be much of an exaggeration to say that PI 34 is simply a charade that protects the teachers who would not fare well in a more serious system of evaluation.

5. PI 34 unnecessarily limits the pool of potential teachers.

PI 34 is very specific about the background and training necessary to teach in a Wisconsin public school. Under PI 34, if a potential teacher has not completed the mandatory teacher training program at a certified school of education, and taken the Praxis I and II exams, he or she is simply seen as unqualified to teach. But current research finds no link between certification and classroom effectiveness measured by student academic growth.13 Nor is this merely a point of interest to researchers. The principals we interviewed regarded PI 34 strictures as a real hindrance to their capacity to hire the best possible teachers for their schools.

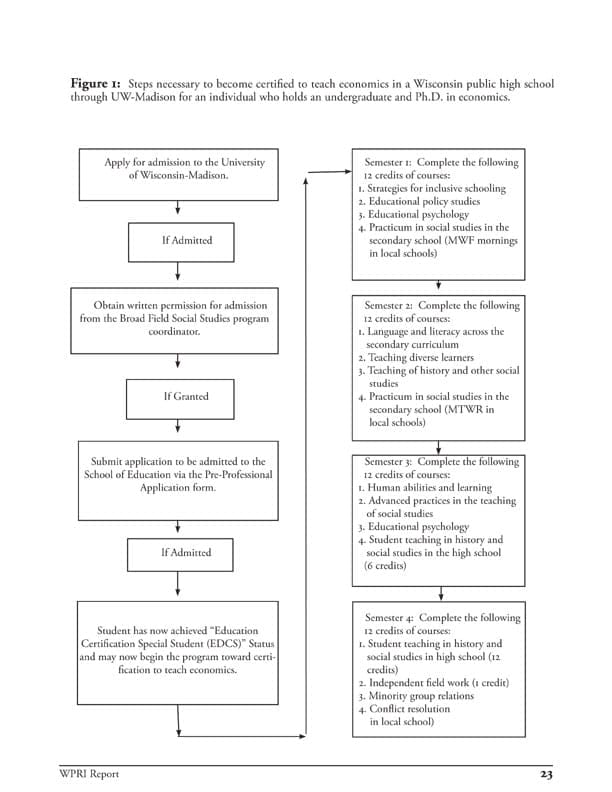

Here we offer an extreme example. Let’s imagine an economist with an undergraduate degree in economics from Harvard and a Ph.D. in the same discipline from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Imagine that this person never took any education courses during these studies. Figure 1 demonstrates the path a person with such a background would have to follow to be certified through Wisconsin’s flagship teacher training program—University of Wisconsin-Madison—to teach Advanced Placement Economics in a Wisconsin public high school. According to PI 34, this individual with the exact same background as current Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke is not qualified to teach a high school economics course without first taking the Praxis exam and applying for admission to both the UW-Madison and its social studies program. Next, Dr. Bernanke would be required to take two full-time years of social studies education courses at UW-Madison, including strategies for inclusive schooling, teaching diverse learners, and human abilities and learning. The former Princeton University economics professor would then need to complete 18 credits of student teaching and take the Praxis II exam (a test of content knowledge). After completing all these tasks, the state of Wisconsin would be willing to certify the chairman of the Federal Reserve to teach a high school course in economics. The story would be more or less the same for mathematicians, scientists, poets, artists, and others with similar backgrounds who might wish to teach.

Figure 1 illustrates the steps Dr. Bernanke would need to take in order to teach the same economics course in a private high school. Essentially, he would send the school his resume, be interviewed, pass a criminal background check, and then begin teaching economics to high school students.

Figure 1: Steps necessary to become certified to teach economics in a Wisconsin public high school through UW-Madison for an individual that holds an undergraduate and Ph.D. in economics.

The actual number of required credits varies slightly across the 33 colleges and universities with approved programs to train teachers in Wisconsin. Nonetheless, as the NCQT report emphasizes, Wisconsin is among the states that stand out for the excessive number of education credits required of prospective teachers. Ironically, it’s likely that most education professors—those tasked with training the state’s teachers—are themselves unqualified, according to PI 34, to teach the K-12 courses they teach others to teach.

6. Regarding teacher competence, PI 34 licensure procedures are toothless.

The vast majority of Wisconsin public school teachers hold a full license for their teaching assignments (see Table 3). In fact, since 2002-2003, only about 1.5 percent of Wisconsin’s teachers (more than 60,000 in total) have been teaching without a license for their teaching assignments. This seems to be a positive finding; Wisconsin’s teachers on the surface appear to be well qualified, as evidenced by licensure rates.

The question is whether licensure rates do in fact guarantee anything about the competence of licensed teachers. They might, if licensure were based on a determination of competence. Then observers could infer from licensure denials that those applicants approved for licensure had met a standard of competence. But that is not how it works in Wisconsin. Nothing in Wisconsin law provides for teaching licenses to be denied or revoked for reasons of competence per se.

What stands out in these statutory and code provisions is that none of the rules authorize the state superintendent to deny or revoke a license for ineffective teaching. Put differently, a license to teach in a Wisconsin public school signifies nothing about a licensed teacher’s ability to teach. This outcome is especially interesting in light of the movement, reviewed earlier, to centralize authority for teacher licensure at the state level, away from local authorities. It was one important step to relocate authority to a state agency; then state statutes could be crafted to ensure that nobody within the agency would attend to matters of competence in exercising that authority.

Table 3: Wisconsin Teacher License Status

Total Full License Emergency License No License | |||||||

| #of FTE Teachers | # FTE | % of Total | # FTE | % of Total | # FTE | % of Total | |

| 2002-03 | 62,525.5 | 59,915.1 | 95.8% | 1,420.5 | 2.3% | 1,189.9 | 1.9% |

| 2003-04 | 61,203.3 | 59,024.9 | 96.4% | 1,012.6 | 1.7% | 1,165.9 | 1.9% |

| 2004-05 | 61,529.3 | 60,259.9 | 97.9% | 857.7 | 1.4% | 411.8 | 0.7% |

| 2005-06 | 61,132.4 | 59,899.6 | 98.0% | 849.1 | 1.4% | 383.6 | 0.6% |

| 2006-07 | 60,975.3 | 59,608.1 | 97.8% | 735.6 | 1.2% | 631.7 | 1.0% |

| 2007-08 | 60,847.6 | 59,587.6 | 97.9% | 800.9 | 1.3% | 459.1 | 0.8% |

| 2008-09 | 61,440.7 | 59,870.4 | 97.4% | 870.6 | 1.4% | 699.7 | 1.1% |

Source: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

It might be objected that Subchapter XII of PI 34 does provide for licensure denials in cases of teacher “incompetency that endangers the . . . education of a pupil.” However, we found that action to deny or revoke a license is taken so rarely that the DPI does not keep any records of it. A DPI representative explained that a license will not be issued if an applicant doesn’t submit fingerprint cards as required, or if an application form is not completely filled out. However, he added, “Our renewal requirements are listed on the website. If a person meets those requirements I cannot think of a single reason to deny them except for criminal background if they submitted all requirements with their application.” So much for licensure assuring that Wisconsin’s teachers are well qualified. But we can be assured that our teachers are not felons and that they can fill out a DPI form completely.

Similar criticisms apply to the current PDP process mandated by PI 34. The principals in our focus groups described a system whereby teachers pick the most favorable review committee possible, wait until the last minute, and then write a PDP crafted to ensure that they will be granted their licenses. There is some debate about how long it would actually take to write a PDP. One principal estimated a half hour.

Why? The union provides, this principal said, a “paint by the numbers” format to make it easy for a teacher to write an acceptable PDP in just a few minutes.

7. PI 34 gives WEAC a privileged position on the Professional Standards Council.

The Professional Standards Council provides a nice illustration of how the PI 34 system is isolated from parents and others outside the education profession. The Council, as specified in PI 34, is heavily influenced by members of WEAC, the state’s teacher union. WEAC is authorized to recommend many of the members serving on the Professional Standards Council. One might say that gaining this position of privilege amounts to a hollow victory for WEAC. We have examined the Council’s minutes and reports as posted on the Council website. It is clear that the group does little. Still, the Council can function more or less as a rubber stamp for whatever the DPI and WEAC have in mind. There is little doubt that this creature of PI 34 will not be likely to examine the serious shortcomings of PI 34. The producers of education dominate state-level governance processes—not the consumers, not Wisconsin’s parents and students.

8. PI 34 presents particular difficulties for urban education.

The litany of rules and regulations mandated under PI 34 presents particular challenges for educators attempting to run and improve urban schools. Many of the principals we interviewed made the point that just because a teacher is licensed doesn’t mean that he or she will be able to teach effectively in an urban environment. Further, the principals complained that many educators who are otherwise highly qualified to teach urban students are locked out of the profession by the PI 34 process. These may be professionals lacking the education credits necessary for certification or older adults who struggle to pass the standardized Praxis II test —particularly, in the mathematics area.

Conclusions

We undertook this study to assess PI 34 in light of the underlying issue associated with occupational licensing. Upon examination, does PI 34 provide substantial protection for consumers? Our main finding is that PI 34 serves primarily to protect and advance the interests of the producers.

PI 34’s weaknesses far outweigh its strengths. The weaknesses include the following: