The following is testimony submitted by Badger Institute Visiting Fellow Angela Rachidi in favor of AB 935 – FoodShare work and FoodShare employment and training requirements and drug testing.

The testimony was submitted to members of the Assembly Committee on Public Benefit Reform on Feb. 8, 2022.

Chairman Krug and members of the Assembly Committee on Public Benefit Reform, thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony related to Assembly Bill 935 – FoodShare work and FoodShare employment and training requirements and drug testing. I want to make three key points.

First, although Wisconsin’s economy has largely recovered from the early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that started in March 2020, employers continue to struggle to find workers, and worker shortages remain a substantial concern for the near term.1

Second, state policies that delink public benefit receipt from employment can make worker shortages worse.

Third, Assembly Bill 935 – FoodShare work and FoodShare employment and training requirements and drug testing – will reduce the work disincentives associated with FoodShare and can help address long-term labor force participation problems in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s Economy

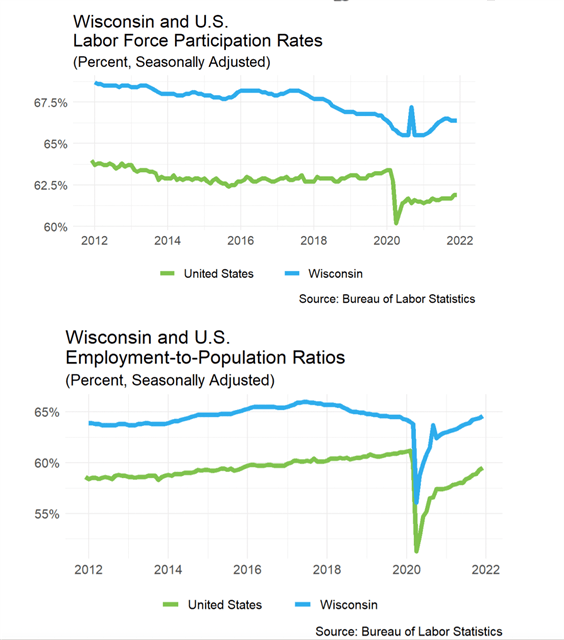

According to data compiled by the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, the unemployment rate for Wisconsin was 2.8 percent in December 2021 and the labor force participation rate was 66.4 percent.2 Both statistics are better than the U.S. as a whole, and rates have returned to pre-pandemic levels. While these data show that Wisconsin’s economy has largely recovered from the pandemic, trends in labor force participation and employment rates suggest that state-level policies to promote work could still be needed.

Wisconsin data compiled by the U.S. Joint Economic Committee show that declines in labor force participation rates (among those 16 and older) predated the pandemic. Similarly, employment-to-population ratios were also declining prior to the pandemic. We can attribute much of this to an aging population, but it also highlights the need to implement state-level policies that maximize employment among working-age people.

Chairman Krug and members of the Assembly Committee on Public Benefit Reform, thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony related to Assembly Bill 935 – FoodShare work and FoodShare employment and training requirements and drug testing. I want to make three key points.

First, although Wisconsin’s economy has largely recovered from the early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that started in March 2020, employers continue to struggle to find workers, and worker shortages remain a substantial concern for the near term. 3

Second, state policies that delink public benefit receipt from employment can make worker shortages worse.

Third, Assembly Bill 935 – FoodShare work and FoodShare employment and training requirements and drug testing – will reduce the work disincentives associated with FoodShare and can help address long-term labor force participation problems in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s Economy

Source: Wisconsin Employment Report, Joint Economic Committee, Senator Mike Lee, January 25, 2022.

Policies That Promote Work

State policymakers have some discretion in how federal benefit programs operate in each state. For example, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly called Food Stamps, gives states the authority to implement work requirements and time limits. Work requirements in SNAP can be important because research shows that SNAP (without a work requirement) reduces employment levels.4

However, the federal government also gives states the ability to waive requirements, which all states did at some point during the pandemic. As I noted in a November 2021 piece for the Badger Institute,5 “To help households cope with the economic fallout of the pandemic, the federal government expanded a range of benefits — more unemployment benefits, cash stimulus payments and increased food and housing assistance. While these expansions in the spring and summer of 2020 may have been justified at the time, lawmakers now need to focus on the economic recovery, including rolling back government assistance.” One such step was to allow federal unemployment benefits to expire in Wisconsin at the beginning of September 2021. It is likely not coincidental that the unemployment rate in Wisconsin dropped to record lows only after that policy change.

Changes to FoodShare in Assembly Bill 935

In an October 2021 report for the Badger Institute, I noted that participation in SNAP (called FoodShare in Wisconsin) had increased dramatically since the start of the pandemic, continuing to increase even as Wisconsin’s economy recovered5. Since that report came out, FoodShare participation has started to decline, but it remains more than 15 percent higher than the months before the pandemic started even though the unemployment rate has returned to pre-pandemic levels.6

One likely reason for the elevated FoodShare caseload is that Wisconsin still has a waiver from the federal government that suspends the work requirement for able-bodied adults without dependent children receiving FoodShare. Assembly Bill 935 rightly ensures that Wisconsin reinstates the work requirement, which 22 other states also currently have.7 The intent of the waiver is to ensure that federal law does not expect states to impose a work requirement on FoodShare recipients when jobs are scarce. Clearly, with an unemployment rate in Wisconsin of 2.8 percent, jobs are not scarce.

Assembly Bill 935 also ensures that the Department of Health Services complies with the 2018 law that required them to impose work requirements on other FoodShare recipients, with exceptions for caretakers and those incapable of work.8 The State Legislature allocated funding for education and training slots for FoodShare recipients subject to the work requirements passed in 2018. The best chance for FoodShare recipients to escape poverty and move up the income ladder is to find employment. FoodShare should help them find employment and require participation in work activities as a condition of receiving benefits. The Department of Health Services should comply with that law.

Angela Rachidi, Badger Institute Visiting Fellow

1 https://www.badgerinstitute.org/BI-Files/Reports/lfprBadgerReport_Labor_Summer2018_web_final_02.pdf

2 https://dwd.wisconsin.gov/press/unemployment/2022/220120-december-state.pdf.

5 https://www.badgerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Badger-Emp-Safety-Net-PB-beta05-1.pdf

6 Department of Health Services FoodShare Data, https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/foodshare/rsdata.htm.