Vol. 22 No. 6

Executive Summary

Each year, the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute conducts a citizen survey that gauges the public’s feelings towards their elected officials. In December 2007, only 10% of the individuals polled said they thought state elected officials represent the interests of the voters. By contrast, 85% said elected officials take care of either “their own interests” or “special interests” first.

Perhaps it is this deep distrust in their state legislators that compels large majorities of Wisconsinites to favor placing term limits on their elected officials. According to the WPRI poll, 72% of respondents favored term limits, while only 22% opposed them. There was no demographic group in the state that did not strongly favor some sort of term limits on Wisconsin elected officials.

In August 2009, Wisconsin Gov. Jim Doyle expressed support for term limits while announcing he would not serve a third term in office. “This is the norm in this country,” said Doyle, adding:

“The president and most governors are limited to two terms by law. Most others have followed tradition. It has largely been Wisconsin’s practice over its history…. And I think this national norm serves good purpose. It keeps the political world from becoming stagnant. It allows new leaders to develop. It gives the voters more choices. It allows us to draw new insights and inspiration from the wellsprings of renewal in each generation.”1

While some argue that term limits take choices away from voters, term limits, in fact, may actually put power back in the citizens’ hands – power that they clearly feel they no longer have.

Over the past several decades, the orientation of state legislators has changed significantly. The Legislature has become an institution whose primary focus is to reelect its own members and to eliminate competition for legislators’ jobs. Such short-term political thinking has cast the state into a deep fiscal hole, from which it may take decades to recover.

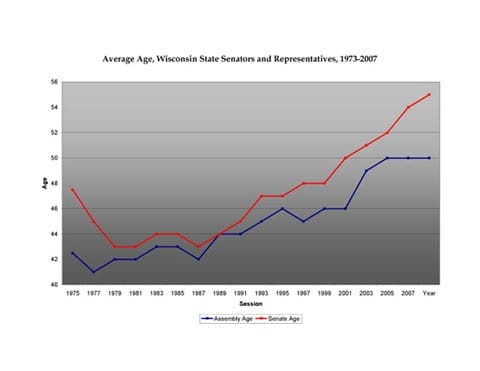

The makeup of the Legislature does not reflect Wisconsin. Most notably, the Wisconsin Assembly and Senate have gotten much older in the past three decades, crowding out younger citizens looking to be involved in state government.

In 1977, the average age for senators and representatives was 43 and 42, respectively. By 2007, those averages had jumped to 55 and 50. This mirrors the 111th U.S. Congress, which is now the oldest it has been for at least the last 20 congresses. (U.S. senators currently average 63.1 years old, while House of Representatives members average 57 years old.)2

Among other changes to Wisconsin state legislators:

- The Wisconsin Assembly is fifth lowest in the nation in turnover rate, while the Wisconsin Senate boasts the seventh lowest turnover rate.

- Between 1963 and 1985, the Legislature averaged 29 new members per session. Between 1985 and 2007, that number had dropped to 19.

- In the past 44 years, only 26 Wisconsin state senators have been defeated in general elections – an average of 1.18 per general election. In that same time, an average of five Assembly incumbents per election have lost. When combined, incumbent Wisconsin legislators have lost only 5.3% of general elections since 1963.

- In 2009, the average Wisconsin state senator has spent 17 years in the Legislature, while the average representative has spent 10 years in the Assembly.

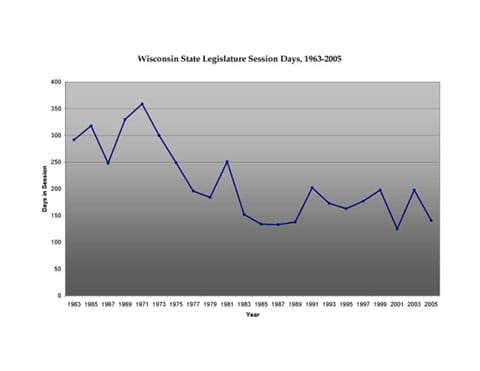

- State legislators spend a lot less time debating bills on the floor than in the past. In 1961, the Assembly and Senate together met 369 days. In 2005, that number dropped to 141, with the Senate meeting 69 days and the Assembly meeting 72 days.

- In the 1970s, the Legislature averaged 2,273 bills introduced per session. Since 1991, the Legislature has averaged 1,697 bills per session, or 25% fewer.

These trends paint the picture of modern legislators who work less, grow older in office, and are less likely to lose their seat in a general election. In effect, for a large number of legislators, their legislative job has become their career.

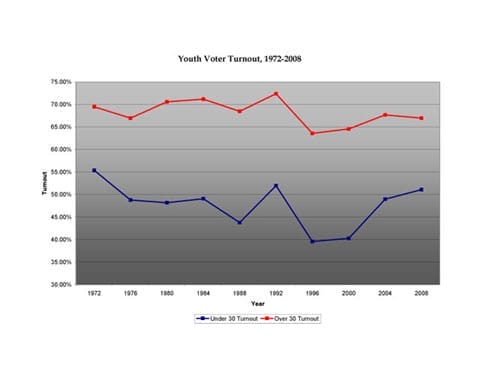

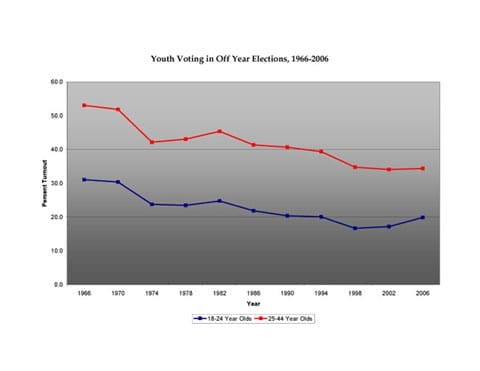

Not coincidentally, the phenomenon of legislators staying in office longer has come at the same time that fewer young voters are participating in politics. While the 2008 election saw a small increase in turnout of voters between ages 18 and 29 (51%), turnout in that age group was still lower than in 1972, when 55.4% of voters under the age of 30 voted in the presidential election.3 Young voters turned out in historically low numbers in 1996 (39.6%) and 2000 (40.3%), before seeing a resurgence in recent years, attributable in part to a 20% increase in young African Americans voting in the 2008 presidential election. Despite these recent gains, turnout among voters under 30 years old remains 16% lower than voters 30 and older, as turnout in the past two elections has increased among older voters as well.4

Young voters have arguably been turned off by aging politicians, who no longer speak to their values and opinions. Despite myriad laws making it easier for young people to register to vote (the “motor voter” law, for instance) and cast their ballots, they are still participating at levels lower than in the past. Also, it is no coincidence that in 2008 they were motivated to come to the polls by a young presidential candidate who hadn’t yet served but one term in the U.S. Senate and had been relatively unknown just four years earlier.

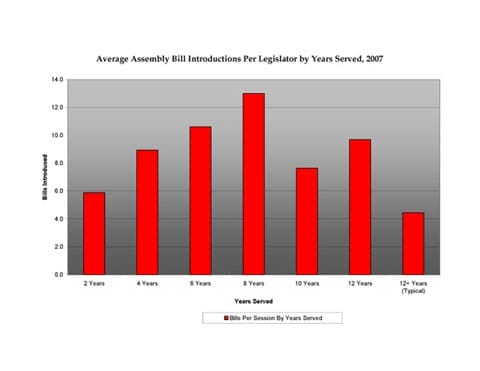

Figure 1

The paucity of younger legislators in Wisconsin has its effect on governance, as well. The 2007 Wisconsin Legislature offers an instructive look at the life of a typical modern legislator, based on experience and workload.

In the 2007 session of the Wisconsin Legislature, the average freshman assemblyperson introduced 5.9 bills. Of legislators with four years in office, the bill introduction average jumped to 8.9 – then continued to climb to 10.6 bills with six years in office, and 13 bills with eight years in office. Then, of those representatives with 10 years in the Legislature, bill productivity began to fall off. The average legislator with 10 years in office dropped to 7.6 bills. Of those with 12 years in office, there was a small increase, to 9.7 bills (although the sample size in this range was very small – only three legislators).

Once they have served more than 12 years in the Legislature, a startling change occurs in Assembly members: Either they begin to draft innumerable bills that are often considered nuisance bills, or they significantly curtail their activity. In the 2007 session, the 20 assemblypeople in this category averaged 4.5 bills per legislator. This is less than the 5.9 bills offered per session by legislators who are newly elected and know very little about the legislative process.

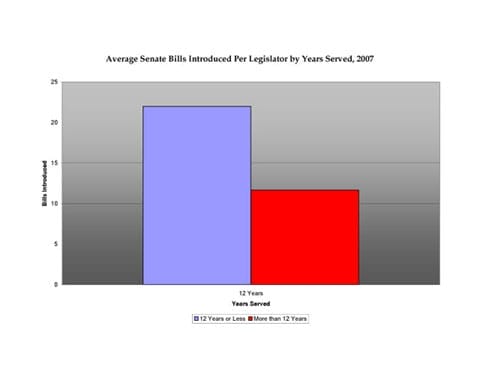

The state Senate mirrors this effect. In 2007, 42% of Wisconsin senators had served in the Legislature for 12 years or less – yet these senators accounted for 55% of the bills introduced in the Senate. Senators with 12 years or less of legislative service averaged 21.8 bills introduced, while senators with over 12 years of service averaged 11.7 bills introduced. Those with the most experience are much less active than their less experienced counterparts.

Had term limits of 12 years been in effect in the past legislative session, 24 Assembly seats (25% of the entire Assembly) would be held by different individuals. Eighteen of the 33 state senators (54.5%) have served more than 12 years (including Assembly service).

If Wisconsin adopted Gov. Jim Doyle’s suggestion to limit elected officials to eight years in office, the results would be even more dramatic: 42 of the Assembly members would be out of office (42.4%), and 25 of Wisconsin’s state senators (75%) would be replaced.

Over the years, the Legislature has granted itself massive advantages during elections, mostly at taxpayer expense. Incumbent legislators have a nearly insurmountable electoral advantage-Wisconsin legislators currently enjoy turnover rates that are nearly the lowest in the nation.

The advantages of incumbency include:

- adding pork projects to the state budget despite the state’s large deficits;

- taxpayer-funded mailings;

- unlimited time to campaign while collecting a legislative paycheck;

- taxpayer-funded legislative staff;

- control over redistricting;

- campaign finance rules that mute opposition.

Challengers rarely have the resources to effectively mount opposition to incumbents, given the benefits legislators enjoy. Consequently, voters are presented with less fair and accurate choices during election season, leading to wildly skewed incumbent reelection rates.

The desire for reelection affects the business of the Legislature. If given the choice between a popular political maneuver and bettering the state as a whole, legislators will often opt for the politically expedient decision. And the state’s citizens suffer as a result. There is no better indicator of this short-term approach to legislation than Wisconsin’s $2.5 billion deficit, one of the largest in America.

Term limits can be an effective means of bringing competition back to Wisconsin elections, offering voters real alternatives. Term limits would reduce the careerist nature of legislative service. While not guaranteeing better decision making, it would allow legislators to govern with a long-term perspective in mind, rather than passing new laws with short-term interests at heart. Finally, it could engage the younger generation in the political process, to which they have grown more disinterested as legislators grow older and stay in office longer.

Introduction

As a young man in the early part of the 1900s, future Hall of Fame baseball manager Casey Stengel played for a barnstorming team, traveling to rural towns to play for big crowds. Oftentimes, their team would pull a fast one on the fans in attendance. Stengel would dress up as a farmer and sit in the stands, pretending to be one of the locals there to see a ballgame. During the game, he would dart out of the stands, yelling that he could do better than the professional players on the field. A phony argument would ensue, and the players would relent, allowing this “farmer” one at-bat. The pitcher would groove an easy fastball down the middle of the plate, and Stengel would knock the cover off of it, pleasing all the fans in the crowd who had dreams of playing baseball for a living.

One hundred years later, Wisconsin state government has become a similar charade, only in reverse. The people in the stands can do better than the professionals.

***

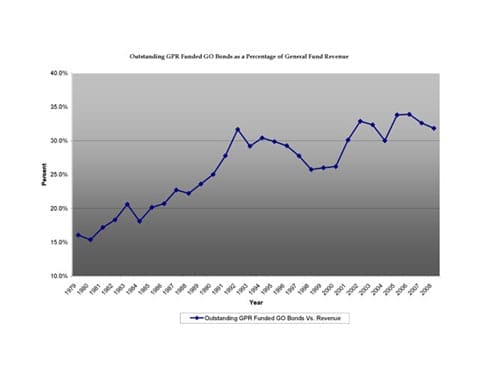

The rapid deterioration of Wisconsin government’s financial condition provides an opportunity to take a fresh look at what put the state in its current predicament. The state has spent itself into the largest deficits in Wisconsin history, and currently has the fourth-largest deficit of any state in the U.S. Wisconsin is worst in the nation in setting aside money in “rainy day” funds, making budget deficits even more painful than in states that had the financial sense to plan ahead. General fund debt as a percentage of tax revenues has doubled in the last three decades, and long-term transportation bonds have been used to finance short-term general fund obligations.

In Wisconsin’s electoral politics, fiscal prudence never seems to prevail over a new or expanded government program. Few legislators want to risk their political career. Thus, elected officials continue profligate spending in their drive for reelection. Very few legislators earn reelection by convincing their voters what they shouldn’t have.

Limiting legislators’ terms in office could begin to reverse the state’s downward slide. With term limits in place, legislators would have more incentive to debate the state’s long-term interest, rather than figuring out how to push off obligations to get them through the next elections.

Wisconsin voters seem to understand the value of term limits since they favor term limits by wide margins. According to a poll taken in December 2007, 72% favored term limits, while only 22% opposed them. There was no demographic group in the state that did not strongly favor some sort of term limits on Wisconsin elected officials. While the push for term limits on a state-by-state basis in the 1990s was largely promulgated by political conservatives, the WPRI poll showed support from liberals, with 58% in favor versus 38% opposing, and Democrats, with 66% favoring the idea and 38% opposing.5

Yet term limits for Wisconsin legislators has never been debated seriously in the Wisconsin Legislature. A 1999 nationwide poll conducted by the Council of State Governments actually found that 76% of politicians opposed term limits – almost the mirror opposite of the public at large.6 In January 2007, a constitutional amendment implementing 12-year limits on terms for most state elected officials was circulated, garnering a meager four legislative co-sponsors. The resolution never had a public hearing and died a quiet, unnoticed death.

Despite overwhelming public support, legislators cannot be convinced to curtail their own terms. Since more elected officials are making careers out of legislative service, they have much more to lose if their terms are truncated. Asking a legislator to give up a secure salary, health benefits, and a pension is asking them to voluntarily forgo potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars.

It was high noon on Feb. 10, 2009, when Wisconsin Senate Majority Leader Russ Decker rose from his cozy brown leather chair to speak. The nation was in the midst of an economic crisis, with the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development about to release numbers that showed the state had lost 72,500 private-sector jobs in the prior year – pushing unemployment up to nearly 8%.

Decker and his fellow Democratic Senate colleagues believed they had just the salve to heal the ailing workforce. On this day, they were pushing through a bill to increase the state’s minimum wage in perpetuity, to help those at the lower end of the economic spectrum.

“The rich are getting richer, and the rest of us are getting stuck behind,” lectured Decker in support of his bill.

He responded to a speech in opposition to the bill by the Republican Minority leader by cracking, “that speech had to be written by George Bush and Dick Cheney.” While intended as a throwaway line meant to invoke the Democratic buzzwords of the day, it served as a harbinger of the seriousness with which the bill was about to be debated.

To the casual observer, Decker himself seemed to be a curious messenger for any bill affecting private employers in the state. After graduating from a bricklaying apprenticeship program at Northcentral Technical College in 1980, Russ Decker has spent 18 years in the Wisconsin Legislature, having first been elected to his northern Wisconsin district in 1990. For nearly two decades, Decker hasn’t had a boss, hasn’t had to make a payroll, hasn’t had to pay for his own health care, hasn’t had to worry about the threat of government intervention killing his job, and hasn’t had to fund any of his own retirement benefits – all while drawing a middle-class taxpayer-funded salary.

Decker has never experienced what most observers would consider meaningful electoral opposition. The last two elections, he’s been opposed by a local oddball who had his name legally changed to “Jimmy Boy” in order to sell “Jimmy Boy’s Frozen Pizzas.” Decker, a Democrat, won each election with roughly 68% of the vote. Yet freshmen entering college today weren’t alive the last time Decker held a job outside of state government.

Reasonable minds can differ as to the actual effect of the bill to raise the state’s minimum wage. But those opposed to the bill have noted the disproportionate effect the change would have on Wisconsin’s younger workers, who are more likely to be working in minimum-wage jobs, and more likely to lose those jobs when costs to employers rise. According to the University of Wisconsin System, raising the minimum wage from $5.15 an hour to $6.80 an hour would result in approximately 768,500 fewer hours of employment in the UW System for students and limited-term employees.7 The tourism and restaurant industries in Wisconsin have long opposed minimum-wage increases, as they argue increased costs would lead to fewer young, seasonal employees. But in a Legislature packed with career politicians, the voices of younger workers were shut out of the minimum-wage conversation.

This bill that affected small businesses and young workers passed the Senate by an 18-14 margin. Joining Decker in speaking in favor of the bill on the Senate floor were Sens. Bob Jauch (26 years in the Legislature), Bob Wirch (16 years), Jon Erpenbach (10 years) and Dave Hansen (eight years). Supporting the bill were interest groups like AFT-WI, the Wisconsin Educational Association Council, the Wisconsin State Council of Carpenters, the Wisconsin Laborers District Council, the Wisconsin AFL-CIO, and the United Transportation Union – groups whose political action committees had given a total of $76,2008 to senators who voted for the bill in the past four years.

***

Voters have noticed. The Wisconsin Policy Research Institute conducts annual polls to gauge the public’s impression of Wisconsin elected officials’ ethics. In December 2007, 2% of poll respondents said they could trust government to do what is right all the time, while 82% said lobbying groups had the most say in how government spends their tax money. When asked whose interests Wisconsin elected officials represented the most, 85% said either “their own interests” or “special interests,” while only 10% said “voters’ interests.” Eleven percent of those polled rated the ethics of Wisconsin politicians as “high,” barely beating out car salesmen at 9%.9

This self-interest has manifested itself in the lack of seriousness with which the Legislature approaches issues. As government has become more complex, long-term thinking has become a scarce commodity. This was made clear as far back as 1986, when Democratic Gov. Tony Earl formed the bipartisan Wisconsin Expenditure Commission to study the state’s spending policies. The commission criticized short-term thinking in budgeting, and recommended Wisconsin develop a long-term government expenditure strategy that would both recognize its citizens’ ability to pay for government services and also improve its competitive position relative to other states.10

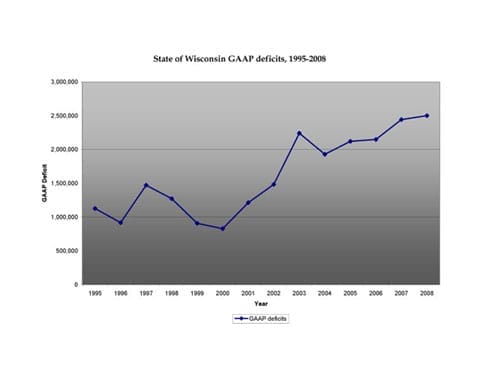

In recent budgets, legislators of both political parties have used debt to support ongoing expenses, plugged the leaking general fund with one-time funds, pushed expenses into later fiscal years, failed to adequately set aside money for a rainy day fund, and offloaded general fund expenditures onto fee-supported appropriations – all of which serve to drive the state further into debt.11 It is no coincidence that the state’s bond rating has continued to fall – the national rating agencies have expressed concern regarding Wisconsin’s fiscal growth.12 Bond rating agencies have identified the state’s lack of general fund surpluses, the lack of a significant reserve or rainy day fund, and the use of one-time revenues to fund ongoing expenditures as credit concerns. These factors have contributed to the state’s ongoing accounting deficit under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).13 Figure 2 demonstrates the growth in state GAAP deficits over the past 14 years.

Figure 2

Source: Wisconsin Department of Administration Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, 1995-2008.

Figure 3

In addition to larger and larger deficits Wisconsin legislators have also been issuing more debt. In the past 30 years, the amount of outstanding general obligation debt in Wisconsin has nearly doubled, from 16.1% of general fund revenues in 1979 to 31.9% of general fund revenues today. Figure 3 demonstrates the increasing amount of debt issued by state government over this time.

In an economic downturn, government spending decisions are made difficult by falling tax revenues. Yet in Wisconsin, these decisions have not been handled in a prudent manner, as can be seen from the growing deficits and increased debt state government has created.

In virtually every case, difficult financial decisions have taken a back seat to short-term, politically expedient decisions.

Take, for example, the governor and Legislature’s decision in 2001 to implement the new SeniorCare prescription drug program in Wisconsin. At the time, state elected officials were trying to craft a budget that closed a $651 million deficit (which would later balloon by $1.1 billion once the full effects of the 2001 recession were known).

Despite warnings of a worsening economy, Republican Gov. Scott McCallum proposed a new state program that would help senior citizens purchase prescription medications. Thus, despite the state facing a large deficit, politicians were able to find money to start a costly new program that appealed to senior voters. In doing so, they caused more fiscal difficulties in subsequent years, as can be seen from the escalating GAAP deficits in Figure 3.Yet, as is increasingly the case, electability took precedence over wise fiscal planning.

There are numerous potential reasons for the state’s unwillingness to budget responsibly. First, it can be argued that Wisconsin is merely following a national trend. At the federal level, entitlement programs have grown rapidly, and the U.S. budget imbalance is rising quickly.

Second, demographics are dictating more demand for government services. As the baby boom generation ages, more pressure is being put on government officials to ensure health care programs will be there for those looking to retire. Generally, these people vote in vast numbers, making them a valuable constituency.

Finally, elected office has proved to be a comfortable career. Where once we had citizen legislatures, now citizens are represented by a class of elected careerists, unwilling to make any decision that would imperil their chances of reelection. This report will explore this last possibility, asking the following questions:

- Is there a growing careerist class in Wisconsin government? Based on the data, the answer is an unmistakable yes.

- What effect has the aging Legislature had on younger voters?

- How did it happen? How many advantages of incumbency have legislators granted themselves over the years?

- Will term limits yield a Legislature that makes different decisions? Does the literature point to a different tenor of legislative business when term limits are implemented?

The Evolution of the Wisconsin Legislature: A Brief Overview

The fact that the Legislature has evolved into an incumbent reelection machine isn’t even news anymore. Those few people who doubt the advantage of incumbency simply aren’t paying attention. In 2009, the average Wisconsin state senator has spent 17 years in the Legislature, while the average representative has spent 10 years in the Assembly.

Furthermore, in the past 44 years, only 26 Wisconsin senators have been defeated in general elections – an average of 1.18 per general election. In that same time, an average of five Assembly incumbents per election have lost. When combined, incumbent Wisconsin legislators have lost only 5.3% of general elections since 1963.

Other statistics give a clearer picture of the growing advantage of incumbency:

- Between 1963 and 1985, the Legislature averaged 29 new members per session. Between 1985 and 2007, that number had dropped to 19 new members per session.

- Legislators are also more likely to be older than in the past. In 1977, the average age of senators and representatives was 43 and 42, respectively. By 2007, those averages had jumped to 55 and 50. By contrast, the average age of Wisconsin’s voting-age public is 46.5 years.

- State legislators spend a lot less time debating bills on the floor than in the past. In 1961, the Assembly met for 185 days and the Senate met for 184 days, for a total of 369 days in session. In 2005, that number dropped to 141, with the Senate meeting 69 days and the Assembly meeting 72 days.

- In the 1970s, the Legislature averaged 2,273 bills

introduced per session. Since 1991, it has averaged 1,697 bills per session, or 25% less.

When taken together, these points give a clearer picture of the modern Wisconsin legislator. They are older, work fewer days, serve longer consecutive terms, and introduce fewer bills.

The Life of a Wisconsin Legislator

Consider the life cycle of hypothetical Wisconsin state Rep. Joe Badger. Rep. Badger has been elected for the first time and has come to the Capitol brimming with new ideas. However, the lawmaking process is complicated and confusing, and takes him a while to learn. As a result, the green freshman legislator may only introduce a couple of bills, most likely causes he championed on the campaign trail that aided him in getting elected.

Then Badger is elected for a second time, and he returns to Madison knowing how to draft bills, use the legislative service agency staff, and get his bills passed. Confident in his knowledge, he becomes more engaged in the process, and begins introducing more legislation.

The third time Badger is elected, he has even more ideas, and the wherewithal to carry them out. His knowledge of the legislative process builds, as does his bill output. Soon, he’s getting better committee assignments (usually tailored to issues in his district), and digging into the weightier issues. He’s using his office account to mail his constituents regularly, and showing up in the local papers as much as he can.

Then one day, Badger wakes up and realizes he’s been in the Legislature for 10 years. Suddenly, the legislative process might not have the urgency it once did. The seat is clearly his to lose. He can keep collecting his full pay, benefits, per-diem payments, and sick leave, whether or not his bill output declines.

By the time Rep. Badger has spent more than 12 years in the Legislature, he becomes somewhat disengaged. His bill output has dropped below what it was when he was a freshman legislator. For 12 years, he’s been dealing with bureaucrats in state agencies who make more than twice what he does, and he figures he’s entitled to any taxpayer-supported pay and benefits that are coming his way. Despite having over a decade’s worth of valuable “institutional knowledge,” his zeal and his output decline.

Rep. Badger’s situation is hypothetical, but hardly atypical. As it turns out, when one looks at the data, this is representative of what happens to Wisconsin legislators throughout their careers – leaving legislative chambers populated with too many disengaged elected officials.

In the 2007 session of the Wisconsin Legislature, the average freshman assemblyperson introduced 5.9 bills. Of legislators with four years in office, the bill introduction average jumped to 8.9 – then continued to climb to 10.6 bills with six years in office, and 13 bills with eight years in office. For representatives with 10 years in the Legislature, bill productivity began to fall off. The average legislator with 10 years in office dropped to 7.6 bills. Of those with 12 years in office, there was a small increase, to 9.7 bills (although the sample size in this range was very small – only three legislators).

Once they have served more than 12 years in the Legislature, a startling change occurs in Assembly members. They begin to disengage from the process. In the 2007 session, the 20 assemblypeople in this category averaged 4.5 bills per legislator. This is less than the 5.9 bills offered per session by legislators who are newly elected and know very little about the legislative process.

There are exceptions, including a handful of long-term legislators who introduce a large number of colorful bills. For instance, 38-year Assembly veteran Marlin Schneider introduced 55 bills in 2007. Among Rep. Schneider’s past introductions have been bills regulating karate instructors, prohibiting implanting microchips in people’s brains, blocking public access to court records, banning the sale of cigarettes containing nicotine, and limiting the maximum weight of University of Wisconsin students’ backpacks.

In 2007, four legislators fell into this category: Reps. Schneider (55 bills), Sheryl Albers (35, including a bill determining pet custody in divorces), Terry Musser (29), and Scott Gunderson (21).

Figure 4 demonstrates the average number of 2007 Assembly bills introduced per legislator, based on years of service. The high-volume senior legislators noted above have been excluded, as they are atypical and drastically skew the sample for those serving over 12 years. When the high-volume senior legislators are excluded, 20 assemblypeople with over 12 years of legislative experience remain.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Several important caveats should accompany this analysis. First, not all bills are created equal. Some are long, detailed, and deal with pressing issues, while others are very simple. For instance, a bill designating a state tartan (2007 AB 212) does not equal a 51-page bill overhauling the state worker’s compensation laws (2007 AB 758).

Second, as legislators gain seniority, many of them take on important committee assignments that take precedent over introducing legislation. For instance, once an assemblyperson becomes co-chair of the Joint Committee on Finance, much of his or her time is spent on the state budget. Rather than drafting legislation in the form of simple bills, these legislators tend to tuck their ideas into the budget – so it may appear that they’re less active legislatively than they are. On the other hand, these “leadership” positions only apply to two or three legislators per house, and don’t

statistically alter the numbers significantly.

Granted, merely counting up bills may be an imperfect way of gauging legislative effectiveness. But when applied to thousands of bills, it does give a good general idea of what happens when legislators serve for long periods of time.

Job Security at an All-Time High

Legislators are facing less and less opposition for their jobs come election time. In fact, Wisconsin has one of the lowest turnover rates for state legislators in the nation, lagging well behind most other states.

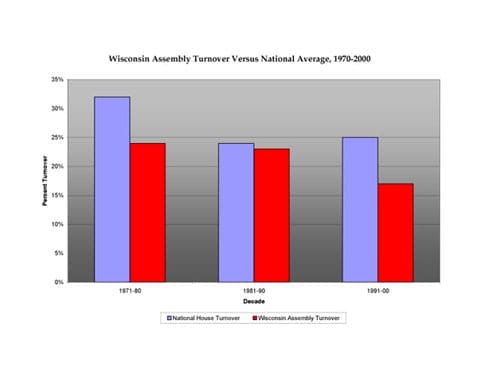

In the 1970s, the Wisconsin Assembly saw a 24% turnover rate. That rate fell slightly to 23% in the 1980s, but then dropped to 17% in the 1990s. Only four states had a lower turnover rate than Wisconsin in the ’90s (Pennsylvania at 11%, Delaware at 13%, New York at 14%, and Indiana at 16%).

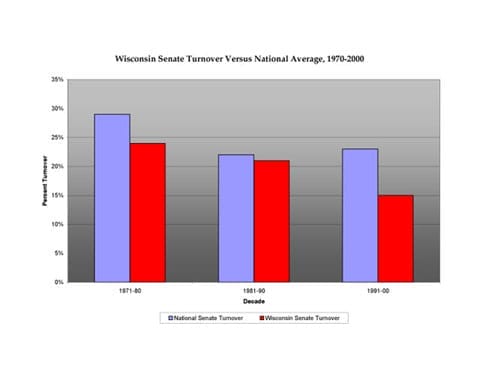

In the Wisconsin Senate the turnover rate fell from24% in the ’70s to 21% in the ’80s to 15% in the ’90s. This gave Wisconsin the seventh lowest turnover rate for state senates nationwide (behind Oklahoma and Delaware, 10%; New York and Indiana, 11%; Pennsylvania 12%; and Nevada 14%.)14

Wisconsin is actually bucking the national trend with regard to turnover rates. In the 1930s, nationwide turnover rates were very high – 51% for state senates and59% for state houses. Over the subsequent six decades, they dropped consistently, down to 22%and 24%, respectively, by 1990.15

But in the 1990s, nationwide turnover rates climbed slightly, to 23% and 25%, perhaps due, in part, to the national term-limit movement that swept through states in that decade.

Yet despite the national uptick, Wisconsin’s turnover rate continued to fall dramatically. Figures 6 and 7 demonstrate the turnover rate in Wisconsin versus the national average for both the state Assembly and state Senate.

Figure 6

Figure 7

The Graying of the Legislature

In addition to gaining more job security, Wisconsin legislators are also growing older. In 1977, the average age for senators and representatives was 43 and 42, respectively. By 2007, those averages had jumped to 55 and 50. By contrast, in 2007 the average age of the population over 18 in Wisconsin was 46.5.

Figure 8 demonstrates the average age of Wisconsin legislators since 1973.

Figure 8

Declining Work Schedule

While the age of Wisconsin legislators has been increasing, their legislative work schedules have been cut back significantly.

“Session days” are the days in which legislators meet in the Capitol on the floor of their respective houses to debate and pass legislation. In 1971, the Wisconsin Assembly and Senate met for a combined 359 session days. By 2005, the number of session days had decreased by 61%, to 141 days in legislative session.

Figure 9 details the decline in legislative session days over the past 40 years.

Figure 9

Combined, these data form the picture of current Wisconsin legislators: older, more secure in their jobs, and working fewer days. All of these traits indicate that modern legislators view the job as a comfortable career option, rather than a temporary public service.

The Aging Legislature and Youth Involvement

Common knowledge in 2009 holds that youth involvement in politics is at an all-time high. Just last year, Time magazine deemed 2oo8 the “Year of the Youth Vote.”

The numbers, however, show a long trend downward with regard to young people and civic involvement. In 1972, 55.4% of voters under 30 nationwide turned out to the polls in election years, with that number plummeting to 39.6% in 1996 and 40.3% in 2000.

Younger voters in midterm (non-presidential year) elections have fallen dramatically. In 1966, voters between 18 and 24 turned out at a rate of 31.1% in non-presidential years. By 2006, that number had dropped to 19.9%. Similarly, in 1966, 53.1% of voters between the ages of 25 and 44 turned out to the polls. By 2006, only 34.4% of voters in that age bracket voted.

Figure 10

This drop in voting has occurred during the same time that legislators have been active in passing new laws to encourage young people to vote. In 1995, the federal “motor voter” bill took effect, which allowed citizens to register to vote when renewing their driver’s licenses. Many states, such as Wisconsin, liberalized their voting laws so that photo identification isn’t even necessary to vote, or in some cases, to even register to vote. Many more states have moved laws allowing “early voting,” which permits citizens to vote at any point for weeks before an election. Yet turnout among young people remains in decline.

It is possible that young voters recoil from politics because of the lack of opportunities they see in elected office. When, as is the case in Wisconsin, legislators grow older in office and rarely lose their seats, younger voters increasingly don’t identify with those in office. Older legislators don’t think like them, don’t talk about the issues they care about, and don’t make much effort to solicit their input.

This increasing lack of interest in civic engagement couldn’t be coming at a worse time for the young people of Wisconsin and the rest of the nation. As noted, Wisconsin has seen a significant increase in debt issued by state government over the past decade – much of which will be paid for by taxpayers over the next several decades. Furthermore, the state has continued to run large structural operating deficits, which are certain to affect future generations, who will have to manage the budget shortfalls left to them by their predecessors.

Gov. Doyle might be on the right track; term limits allow new, younger leaders to develop. They “allow us to draw new insights and inspiration from the wellsprings of renewal in each generation,” as he said in his retirement speech.

Yet Wisconsin has a system of laws that makes it much more likely incumbents will be elected. It is the immense incumbency advantage set out in state law that keeps younger, more active legislators from taking office. These advantages are detailed in the next section.

The Wisconsin Legislature: Looking Out for Number One

On September 25, 2008, state Sen. Spencer Coggs was sitting on a televised panel, discussing the state of politics in Wisconsin. When one of his fellow panelists16 brought up the issue of term limits as a potential way to get state government moving again, Coggs chuckled, saying:

“We do have term limits in the state of Wisconsin. We call them elections. And I want them to stay that way, because I don’t want the bureaucrats to have the only institutional memory in the state of Wisconsin.”17

Coggs was first elected to the Wisconsin Legislature in 1982. Since joining the Senate, he has never had anyone run against him.

This is the most common retort to term limits – people are free to choose their elected officials, and if they keep sending the same people back year after year and decade after decade, then isn’t that their right?

Obviously, the people’s ability to choose who represents them is a fundamental right, and should be taken seriously. But it is also fair to ask on what basis people are reelecting their legislators. Are elections a fair fight? When a legislator sits in office for a decade, are voters getting the information they need to make an informed decision?

As noted, in the past 44 years only 26 Wisconsin state senators have been defeated in general elections – an average of 1.18 per general election. In that same time, an average of five Assembly incumbents per election have lost. When combined, incumbent Wisconsin legislators have lost only 5.3% of general elections since 1963.

These numbers suggest the power of incumbency is a daunting obstacle for potential challengers. This is, in large part, due to the advantages incumbents have granted themselves through the legislative process. Over time, the state Legislature has created many advantages for incumbents, leaving challengers with too large of a hill to climb.

The advantages of incumbency are myriad, and some of them are unavoidable. For instance, when candidates first win, the reputation they gain as a “winner” is something they can trade on in future elections. The name recognition incumbents gain merely by representing their constituents for the first two or four years is also helpful.

However, there are a number of other tools legislators grant themselves.

WORK SCHEDULE

One of the primary benefits of incumbency can be found in how legislators structure their work schedule. On April 22, 2010, legislators will walk out of the Capitol having completed the 2009-11 biennium. Between April and November, they will be free to do all of the campaigning they want – going door to door, making fundraising calls, and attending church fairs. The entire time, they will be collecting a state paycheck and benefits.

On the other hand, prospective challengers essentially have to quit their job for five months to do the campaigning they would need to do to be competitive. There’s no way they could do all the retail politics and fundraising they would need to do in their off hours to compete with the incumbent. Even if they tried to maintain their job while running for office, it would virtually guarantee that they couldn’t see their family until election day. These are huge disincentives for successful businesspeople to run for office in Wisconsin.

TAXPAYER-FUNDED MAILINGS

One of the most challenging aspects of running a legislative campaign as a non-incumbent is trying to get your message to the voters. Doing so takes raising money, and running up tens of thousands of dollars in printing and mailing costs to get your literature to citizens of the district.

Incumbents have no problem delivering campaign materials to the voters, because the voters pay for it. Every legislative session, incumbent lawmakers are permitted to send “legislative updates” and “questionnaires” to their constituents in the form of mass mailings. Of course, nobody would argue that lawmakers shouldn’t be able to keep in touch with their constituents. Virtually any voter would agree that constituent service is a large part of the job citizens expect their lawmakers to perform.

However, a review of newsletters mailed out by legislators during the 2007-08 session shows that many of these taxpayer-funded fliers appear to have very little informational value to voters. They are indistinguishable from campaign literature, bragging about projects legislators were able to bring back to their home districts, sprinkled with photos of legislators reading to children, giving speeches on the floor, attending bill signings, and meeting with veterans in their district. They list many of the bills authored by the legislator, with flowery, hagiographic text written by that legislator’s staff.

Some newsletters are mailed out as questionnaires, allowing constituents to answer questions written by the legislator in order to get “feedback.” Of course, these questions are often heavily slanted in favor of the legislator’s personal views. Then, the incumbent can use these manufactured poll results as talking points during the campaign, perhaps even using the database with the poll results as a guide for targeting voters during the campaign. Voters who answer a questionnaire from a legislator saying they believe in the right to carry a concealed weapon are infinitely more likely to get a pro-gun literature piece from that legislator come election time.

These questionnaires (which are statistically invalid, since they are voluntary) contain questions such as this one, from a survey by Rep. Mary Hubler:

“The governor has proposed that big oil companies be taxed 2.5% per barrel on profits from sales in Wisconsin. This tax could not be passed on to consumers at the pump. Do you agree with this?”

This question apparently is meant to generate a specific answer in support of Rep. Hubler’s position rather than to actually gauge the opinion of her district. This question is representative of the hundreds of other biased questions found on these phony “surveys.”

During the 2007-08 legislative session, the Wisconsin Senate spent $568,000 printing and mailing these newsletters and questionnaires. The Assembly spent $692,000 on various forms of newsletters, questionnaires, mailing services, contact cards, newspaper inserts, and other taxpayer-funded forms of constituent contacts.

In this time period, legislators sent out 152 different newsletters. Some chose to do one large newsletter, while others mailed one newsletter and one questionnaire. Some, like state Sen. Sheila Harsdorf and state Rep. Scott Suder, chose to do multiple newsletters, targeted at smaller, specific constituencies.

BRINGING HOME THE BACON

One of the most powerful tools incumbent legislators have is the ability to steer funding and projects back to their districts, even in times of fiscal distress. In 2005, while the state was wrestling with a $1.6 billion deficit, legislative Republicans were able to find $1.1 million in new money for a new engineering initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Rock County. This project was in the district of state Rep. Debi Towns, one of the GOP’s most vulnerable members. (Towns lost her next election anyway, as she was swept away in the 2006 Democratic tidal wave that cost Republicans control of the state Senate.)

In 2009, with Wisconsin state government staring at a $6.6 billion budget deficit, legislative Democrats were able to find millions of dollars in new spending for projects to aid in their reelection efforts back home. After weeks of rhetoric about how the 2009-11 budget will make the “tough” decisions and “cut” millions of dollars in spending, legislators included the following projects in the budget approved by the Joint Committee on Finance:

- $44.5 million, mostly in bonds, for a University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire education building, represented by Sen. Kathleen Vinehout (D-Alma) and Rep. Jeff Smith (D-Eau Claire).

- $13 million for the Wisconsin Rapids armory, represented by Sen. Julie Lassa (D-Stevens Point) and Rep. Marlin Schneider (D-Wisconsin Rapids).

- $28 million in bonds for a School of Nursing facility at the UW-Madison. Sen. Judy Robson (D-Beloit), a nurse who sits on the committee, has long backed her profession in the Legislature.

- $6.6 million for a Yahara River project in Dane County; the county is represented mostly by Democrats, including the committee’s co-chairmen, Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Madison) and Sen. Mark Miller (D-Monona).

- $5 million for the Bradley Center Sports and Entertainment Corp. in downtown Milwaukee, represented by Sen. Spencer Coggs (D-Milwaukee) and Rep. Leon Young (D-Milwaukee).

- $4 million for planning a joint museum for the State Historical Society and Department of Veterans Affairs; an area served by Pocan, Miller and other Dane County legislators would benefit.

- Up to $1.25 million for Manitowoc Road in Bellevue, represented by Sen. Alan Lasee (R-De Pere) and Rep. Ted Zigmunt (D-Francis Creek).

- $800,000 for the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin; the center has locations throughout the state.

- Up to $500,000 for Washington Street in Racine; Democrats Sen. John Lehman, a committee member, and Rep. Robert Turner represent the area.

- $500,000 for an environmental center in a park that borders Madison and Monona; the two cities are represented by the committee’s co-chairmen.

- $500,000 for the Oshkosh Opera House; Republican Sen. Randy Hopper and Rep. Gordon Hintz, a Democrat, represent Oshkosh.

- $500,000 for Eco Park in La Crosse, represented by Sen. Dan Kapanke (R-La Crosse) and committee member Rep. Jennifer Shilling (D-La Crosse).

- Up to $430,000 for Highway X in Chippewa County, represented by Sen. Pat Kreitlow (D-Chippewa Falls) and Rep. Kristen Dexter (D-Eau Claire).

- Up to $400,000 for State Street in Racine, represented by Lehman and Turner.

- $300,000 for the AIDS Network in Madison, represented by Pocan and Senate President Fred Risser (D-Madison).

- $250,000 for a bridge on S. Reid Road in Rock County, represented by Robson and Rep. Chuck Benedict (D-Beloit).

- $250,000 for the Madison Children’s Museum, represented by Pocan and Risser.

- $125,000 to remodel an Eau Claire library, represented by Kreitlow and Dexter.

- $100,000 for Huron Road in Bellevue, represented by Lasee and Zigmunt.

- $100,000 for the Stone Barn historic site in Oconto County, represented by Sen. Dave Hansen (D-Green Bay), who sits on the committee, and Rep. John Nygren (R-Marinette).18

OFFICE STAFF

For the entirety of their terms, legislators have office staff to coordinate their legislation, deal with constituents, serve as media advisers, staff committees, and take care of any other concerns. A legislator’s immediate staff is expected to make that sure that the legislator is presented as positively as possible in the district. Any staff member who doesn’t accomplish this task isn’t likely to be around for very long. Furthermore, each staff member has access to state-funded computers, Internet, printing, and office phone usage. The Legislature’s technology bureau has created a sophisticated program that allows legislators to track constituent contacts and concerns – concerns that are often addressed during the campaign.

A typical Assembly representative has two staff members, although that number can go as high as seven for legislators in leadership positions. Additional staff is generally granted for representatives on more prestigious committees. A typical Senate office has between three and four staffers, with the current high being eight staff members in the Senate Minority leader’s office.

The Legislature also employs three primary service agencies – the Legislative Fiscal Bureau, Legislative Council, and Legislative Reference Bureau19 – which are all on call to answer any questions legislators have about impending issues. Legislators may also request memos from each of these bureaus, often giving them ammunition for press releases used to make political points come election time.

The existence of these service bureaus gives incumbent elected officials instant access to information and analysis that isn’t available to the average citizen. A challenger who makes a charge against an incumbent can instantly be buried by a mountain of facts and figures generated by the Legislature’s legal experts.

The Legislature is expected to spend $149 million20 in the next budget to pay the cost of legislative staff and service agencies. This is an advantage regular citizens don’t have access to when mounting a challenge to these incumbents.

MEDIA

It is only natural that incumbent legislators have higher name identification than potential challengers. Part of their job, after all, is communicating with their constituents.

But the media opportunities that the incumbent is able to generate through holding office enhance name identification. Current officeholders are able to call press conferences, issue press releases, and make calls to news outlets. When a legislative issue of importance is breaking, reporters call them looking for quotes. Radio talk show hosts hustle to get them on the air to see what they think.

In many cases, incumbent legislators have a staff member on their payroll who is charged with dealing with the media. These staffers, when effective, form personal bonds with reporters, enabling them to garner more favorable coverage for their legislators and helping them move their legislative agendas forward.

COMMITTEES

When a legislator’s party takes control of one of the houses of the Legislature, it is likely that each lawmaker in the majority party will be assigned to chair a committee.21 Chances are that the committee they chair will be constituted to give them the chance to maximize their exposure to issues that are relevant to their district.

For instance, a state senator whose district contains a large farming community and a number of ethanol plants might find himself the chair of the Rural Issues, Biofuels, and Information Technology Committee. A senator like Democrat Jim Holperin, who represents the north woods and whose district is heavily reliant on state highway funding, might chair the Transportation, Tourism, Forestry, and Natural Resources Committee. A senator like Democrat Kathleen Vinehout, with an agriculture-heavy district that contains the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, might have the opportunity to chair the Agriculture and Higher Education Committee. In the 2009-11 session, all of these committees exist, and all are paired up with legislators as described above.

Chairing these committees gives these elected officials tremendous power over the legislative process as it pertains to the issues that affect their districts. Committee chairs become the last word in the legislative process when deciding what bills move forward.

One can be fairly certain that no transportation issue that adversely affects the northern portion of the state will make it out of the committee as currently constituted. Conversely, any agricultural issue that may help the farmers of the Eau Claire area will probably get more than a fair hearing in the Agriculture and Higher Education Committee.

Chairing a committee also allows legislators to take their committees on the road for hearings in their districts. On occasion, chairs will schedule a hearing in their own district in order to get more face time with their constituents. The cost of relocating the committee for the day is borne by the state’s taxpayers.

Committees are also important for legislators who serve on the Joint Finance Committee (JFC), the powerful budget-writing panel that assembles the state budget every biennium. Before the budget process starts, JFC holds hearings around the state – almost always in the district of a sitting member of the committee. At these hearings, which go on for hours, the home legislator is often asked to chair the meeting.

THE WISCONSIN ELECTION CAMPAIGN FUND

In 1977, the Legislature implemented the Wisconsin Election Campaign Fund (WECF), in which state general-purpose revenue is granted to candidates for state elected office to aid in running their campaigns. Ostensibly, granting these funds served the purpose of lessening special interest influence on campaigns throughout the state, and allowed challengers to afford the cost of running for office. But in the 22 years since enactment of the program, its mission appears to have changed, mostly to benefit sitting legislators.

The WECF is funded from an income tax checkoff, which allows individuals filing their taxes to direct one dollar from the general fund to the WECF. Since choosing that option does not increase tax filers’ liability or reduce their refund, that dollar from the general fund is a dollar that otherwise would have been spent on any number of general fund programs, from school aids to Medicaid. So while campaign finance reform advocates consider the fund to be a “voluntary” contribution, all taxpayers eventually pick up the tab for the program through higher taxes, to make up for the money diverted out of the general fund.

Candidates are notified if they are eligible to receive the WECF grant following the primary election. Requirements for receiving the grant are:

(a) if the office sought is a partisan office, the applicant received at least 6% of the total votes cast in the primary and won the primary or if the office sought is a nonpartisan office, the applicant has been certified as a candidate;

(b) the applicant will face an opponent in the general election; and

(c) the applicant received the required number of qualifying individual contributions of $100 or less. (Candidates for state senator and representative to the Assembly must raise 10% of the spending limit for the applicable office in individual contributions of $100 or less.)

If eligible, a legislative candidate receives a check from the state no later than three days following the fourth Tuesday in September.

Between 2002 and 2008, 173 candidates have received a grant from the WECF: 133 Democrats, 39 Republicans, and one Independent (77% Democrat, 22.5% GOP). In those four election cycles, $1.14 million has been granted to Wisconsin legislative campaigns. Of the 173 receiving the grant, 129 candidates lost – and of those 129, only three (2.3%) were incumbents.

Of the 47 winners who took the grant, 38 (81%) were incumbents. Of the nine winners who were not incumbents, six beat incumbents (Reps. Hines, Freese, Skindrud, Loeffelholz, Weber, and Kreibich) and three ran in open seats.

A review of WECF allocations shows that funds generally go to campaigns in which the outcome was never in doubt. Between 2002 and 2008, the average vote received by winning candidates who took WECF money was 63.4%. Losing candidates who accepted WECF funds received an average of 39.3% of the vote. Generally, taxpayers have been funding non-competitive races, either way.

What is even more troubling is how the fund has been used by incumbents to seemingly pad their already strong incumbency advantage, at taxpayer expense.

Take, for example:

- In 2002, Republican Steve Nass accepted a grant of $7,013, then went on to beat Leroy Watson 87% to 13%. Nass took a grant of $5,963 in 2006, beating nudist Scott Woods 66% to 34%.

- In 2004, Democrat Joe Parisi beat Republican Dan Long 75% to 25% in one of Wisconsin’s most liberal Assembly districts. In 2006, Parisi decided he needed the grant, and beat Long once again by a 75%-to-25% margin. Long, of course, took the grant both times. Total cost to the taxpayer for the two campaigns: $18,600.

- In 2004, Democrat Mark Pocan took a grant of $5,574 and beat Republican James Block 86% to 14%. Block also received a WECF grant.

- In 2002, Democrat Bob Jauch accepted a grant worth $11,932, then went on to roll over Republican Gregg Condon by a 62%-to-38% margin. In the next election, Jauch once again took a grant, this time worth $2,425, and beat Shirley Riedmann by an identical 62%-to-38% margin.

Among the most attractive features of the WECF program for campaign finance reform advocates are the spending limits that are required of grant recipients. Candidates who receive WECF money must agree to limit their campaign’s total spending, unless their opponent refuses to do so – in which case, they may exceed the spending limits.

Uniform spending limits virtually always benefit the incumbent – in order to overcome the immense incumbency advantage, challengers have to spend more than the current officeholder. That is why incumbents should be happy when their challenger receives public money for their campaign – it almost guarantees that the challenger will be unable to spend enough to oust them from office. And that is why 126 of the 129 grant-taking candidates who have lost have been challengers.

So while 22 years ago, the WECF may have been touted as an opportunity to inject more competitiveness into elections, the effect may have been the exact opposite. Incumbents take the grant to pad their already large campaign chests, while challengers take the grant and are hamstrung by the spending restrictions.

REDISTRICTING

Perhaps the most powerful tool used to determine elections is the setting of district boundaries, which is once every 10 years. It is the Legislature itself that sets these boundaries, thereby micromanaging the electoral composition of each district to its liking.

Even the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau recognizes the inherent politicization of the redistricting process. An LRB paper describing the redistricting steps in Wisconsin states, “Redistricting is an inherently political process, as it is done by an elected legislature that will have to live with the political consequences of the result. Political considerations, both of parties and of individuals, will underlie every decision made.”22

In many states, including Wisconsin, redistricting has been subjected to undisguised partisanship during the legislative process. Recognizing the stakes for their future electoral prospects, each party has fought tooth and nail to gain an advantage in the redistricting process. In the past three redistricting processes, federal courts have had to step in and partially redraw the districts created by Wisconsin legislators.

Wisconsin will redraw its legislative districts in 2011, with the first elections in the new districts being held in November 2012

ELECTION ADMINISTRATION

Incumbents not only control the actual voting process, they also control the manner in which campaigns are run. For years, the Legislature has been attempting to regulate campaign advertising during elections, with some legislators decrying the ability of third parties to run ads.

In many cases, if a challenger is to have a chance against an incumbent, these third-party ads are crucial to making up the recognition gap. Consequently, if the Legislature were to ban these ads, as Wisconsin legislative leaders have indicated they intend to do, it could be a substantial boon to incumbents. Challengers simply do not have the connections and fundraising framework to compete with longtime incumbents, and the aid they receive from independent groups (aside from being a First Amendment free speech issue) can often close the credibility gap. Regulating the timing and content of political expression during campaigns could have a significant effect on who has a chance to gain elective office.

The Term Limit Experience

In the early 1990s, states around the country began adopting term limits for their elected officials. In 1990, California, Oklahoma, and Colorado were the first to limit the terms of their state legislators. From 1990 to 1995, legislative term limits passed in 18 states, with an average of 68 percent voter support. In November 2000, Nebraska became the 19th state to limit the terms of state legislatures.

By the end of 2002, term limits had affected well over 700 legislative seats in 11 states.23

In 20 of the 21 states that eventually adopted term limits, the limits were instituted via citizen initiative. (Since then, five states have had their term limits on congressional representatives overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, which has struck down the ability of states to limit their federal representatives.)

State legislatures never impose term limits on themselves – it almost always takes the force of a public vote to force limits on lawmakers’ terms. This is a primary reason no new term limits have been enacted since 2000. Virtually all the states that allow for direct citizen initiative have enacted them, and it is unlikely that states without such a framework will pass them without intense public pressure.

During the wave of term limits enacted in the 1990s, many of the arguments for and against limits became familiar to the American people. The primary arguments for term limits broke down roughly into these areas:

Diverse Representation– Term limits, it is argued, would provide more culturally diverse legislators. Since long-term legislators wouldn’t be able to cling to their seats for decades, it would improve the election chances of women and minorities, as well as younger, more energetic people with new ideas. More regular citizens, with a stronger sense of the private sector, would run government in a more efficient and responsible manner.

Term limits would also force legislators to join the private sector and live under the rules they have created, which may have the effect of retarding overzealous regulation. After South Dakota Sen. George McGovern lost his reelection bid in 1980, he returned home to operate a hotel, finding that it was a little more difficult than he’d thought. “I wish someone had told me about the problems of running a business. I have to pay taxes, meet a payroll – I wish I had a better sense of what it took to do that when I was in Washington,” McGovern famously complained.24

“The Burkean Effect” – Coined by George F. Will in his 1992 book Restoration, the “Burkean effect” refers to a change in philosophy that gives legislators incentives to shift away from coddling their constituents and toward looking at state issues as a whole. In 1774, after being elected to the British Parliament, Edmund Burke gave a speech in which he rejected the idea that he should be bound by the “instructions” handed down to him by his constituents. Burke said that the wishes of his constituents should be given great weight, but he owed them something much more important than mere obedience; he owed them his “judgment.”25

Under term limits, the argument goes, legislators would be less inclined to patronize their constituents, and would be more inclined to look at the larger picture with regard to governance. Instead of merely bringing back as much pork as possible to the voters, term-limited legislators could use their unburdened consciences to govern for the good of all, not just a few. In doing so, legislators would actually be able to say no to spending constituencies that lobby them so heavily for legislation and funding.

A Blow to Corruption– Term-limit advocates view legislative careerism as a breeding ground for corruption. Legislators in office over the span of decades see their power expand, making them ripe targets for special interests looking for favors. As the years wear on, career legislators form long-term relationships with lobbyists, becoming more susceptible to their temptations.

Those opposed to term limits also have a litany of arguments against capping legislative careers. They say that legislators should be in office to see the programs they create through to fruition. They believe that elected officials should be able to use all their legislative experience and institutional knowledge to run state government, and that capping terms gives too much influence to legislative staff, who would serve longer than their bosses. They also argue strenuously that term limits weaken the legislative branch relative to the executive branch.

Numerous studies regarding the effects of term limits have been conducted, although comparing states is an extraordinarily difficult endeavor. Many term limits passed years ago have not even gone into effect yet, or are very new. The sample size of states with term limits is very small, and our experience is not vast. Furthermore, the behavior of legislators – how much time they spend working on legislation versus answering constituent calls, how much influence they feel they have, etc. – is not easily quantified. Clearly, legislator behavior is affected by much more than the length of their terms.

Of course, that doesn’t stop many groups opposed to term limits from issuing their own studies of the effects of term limits. In 2006, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) issued a paper entitled “Coping With Term Limits: A Practical Guide.” NCSL is an organization that exists to represent legislators. The report bemoans the lack of “civility” and “collegiality” under term limits, arguing that if legislators serve longer terms together, they get to be better friends.

In 2006, a comprehensive study by four university researchers attempted to measure the primary arguments for term limits. The report, entitled “The Effects of Term Limits on State Legislatures: A New Survey of the 50 States,” examined the efficacy of term limits in the states that had enacted them in the 1990s.26

The report (also known as the “Carey Report,” after lead author John M. Carey of Dartmouth College) found that many of the “compositional” effects promised by term-limit proponents are somewhat exaggerated. Their data showed very little evidence that term limits promoted the election of more minorities to state legislatures; however, term-limit states were more likely than non-term-limit states to elect women. They admit, however, that this may merely be the natural progression of legislatures, and not necessarily attributable to more seats opening up as a result of term limits.

The report does, however, find substantial differences in term-limit states with regard to legislative priorities (the “Burkean effect”). The authors found that legislators in term-limit states spend less time keeping in touch with constituents than do those in states without term limits.27 Furthermore, they report that term-limited legislators spend far less time than their colleagues in non-term-limited states securing government money and projects for their districts.

Critics of term limits may be able to look at certain term-limit states and argue that the “Burkean effect” hasn’t materialized. For instance, California enacted term limits in 1990, and 19 years later, its finances remain in shambles.

However, the California example is why studying the actual effect of term limits is so difficult. While citizen initiative has brought California term limits, it has also brought the state numerous laws passed by public vote that restrict the legislature’s ability to govern. For instance, Proposition 13, passed in 1978, limits the amount of tax individuals may pay on their homes to 1% of the cash value of the property. That puts enormous pressure on state government to fund local governments. Furthermore, California’s constitution requires a two-thirds legislative majority to pass a budget, which drastically changes the budgeting process. It has been argued that the need to woo so many votes to pass a budget leads to excessive debt issuance, as borrowing seems to be the one budget tool on which both parties agree.

When polling state legislators as to whether they rely more on “constituents” versus “conscience,” legislators in term-limit states were much more likely to rely on “conscience,” especially as they moved closer to the end of their terms. This is vital, as it strongly suggests a greater likelihood for long-term fiscal planning, as opposed to the short-term chicanery often seen with legislators seeking reelection.

This “behavioral effect” for legislators is by far the most important shift that we see in states with term limits. While it certainly would be nice for legislatures to be more culturally diverse, how legislators vote and the official actions they take trump virtually any other change they might experience.

Imagine Wisconsin, for example, if legislators weren’t constantly focusing on the next election every even-numbered year. For over a decade, state elected officials have balanced budgets with questionable financial maneuvers and one-time money, each leading to a larger deficit.28 Yet any legislator who showed the courage to cut spending or lay out a plan to balance the budget would be criticized bitterly, perhaps costing votes in the next election. If there were enough legislators who didn’t have to concern themselves with elections, it might be an altogether different document – instead of being essentially a short-term political bill, it might take into account the state’s long-term fiscal health.

The Carey Report also addresses one of the primary points raised by term-limit opponents. Through the process of interviewing legislators, the report’s authors

found that many elected officials felt that the legislative branch in their state had indeed lost power relative to the executive branch.

In their term-limit study, NCSL measures “legislative strength” in part by how often the legislature amends the governor’s budget document:

“A study of four term-limited legislatures, for instance, revealed that legislative adjustments to governors’ budget proposals have declined significantly in all four states since term limits took effect. This shift in power reflects the key problem term limits creates: inexperience. Inexperienced legislators do not always know the questions to ask of experienced executive branch administrators and agency directors. Legislatures that lack veteran leadership may hesitate to challenge the governor’s budget.”29

Earlier in this report, a list of many of the new provisions added by the Wisconsin Legislature to the governor’s proposed budget is offered. In adding dozens of pork projects, none of which had been subjected to a public hearing, the Legislature spent millions of dollars more, at a time when the state was attempting to close a $6.6 billion deficit.

The Legislature’s recrafted budget also delays debt payments, approves $140 million in new bonding to balance the general fund budget, and contains dozens of policy items (including making car insurance mandatory) that have nothing to do with solving the state’s budget deficit. According to the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, the 2009-11 budget creates a $2.3 billion structural deficit for the 2011-13 biennium.

Both the Carey Report and the NCSL study question the lack of “experience” of legislative leadership in term-limit states. Term limits, NCSL argues, “make the learning curve steep for new leaders, but also make it more difficult for leaders to exert influence on their caucus.”

While the NCSL contends that term-limited leaders don’t have enough experience, it is appropriate to ask, “experience doing what?” Experience addressing serious budget shortfalls by applying questionable short-term fixes? All of this supposed “experience” by the Legislature’s elders has gotten the state into a disastrous fiscal situation, with no end in sight.

Think back to Spencer Coggs’ declaration that term limits would cause a loss of “institutional memory” in the Legislature. To that, Wisconsinites would likely say, “Amen!”

Conclusions/Recommendations

As noted, the overwhelming majority of states with term limits have had them imposed via citizen initiative. Wisconsin’s Constitution does not allow for a direct citizen legislative process, so any change to state law must go through the Legislature. (There is a direct legislation law that allows citizens to take local ordinances directly to the voters.) And as noted, the chances of the Wisconsin Legislature imposing term limits on itself are about the same as the Legislature turning the State Capitol into a bed-and-breakfast.

Even if citizens wanted to bring the term-limit issue before voters in the form of a constitutional amendment, it would have to clear the Legislature. Constitutional amendments must pass both houses in two successive legislative sessions before they are put to the voters via referendum, which would seem to have a very good chance of passing. The only thing standing in the way of this public vote are the very legislators whose terms would be limited.

Yet the discussion of term limits in Wisconsin is both timely and instructive. According to poll results, voters seem to have recognized that the Legislature has become a self-perpetuating institution that is isolated from the public.

It is important to recognize how far off track state legislators have gotten with regard to the state’s fiscal priorities. In Wisconsin, career legislators have damaged state finances to the point that taxpayers may be bailing out the government for decades. The short-term strategies of using one-time money, raiding various disparate state funds, and borrowing to fill the general fund could possibly land a private-sector executive in prison. Yet for Wisconsin’s career legislators, such maneuvers are simply business as usual – as long as the “business” is focusing on reelection and avoiding difficult decisions.

As demonstrated in this report, the typical legislator’s work product significantly diminishes after the 12th year in office. Limiting Assembly representatives and state senators to 12 years (six terms for the Assembly, three terms for the Senate) would allow for lively campaigns and political debate in areas of the state that don’t get to have those conversations as long as their incumbent legislators wear the protective mantle of incumbency.

Endnotes

1 http://www.wispolitics.com/index.iml?Article=167406 – Some, including this author, have questioned Gov. Doyle’s recent conversion to term limits, as he faced some of the lowest approval ratings of any governor in the U.S. at the time he announced he would not be seeking a third term. Additionally, Doyle served three terms as Wisconsin attorney general and raised money for a third gubernatorial term up until he made his announcement that he would not be running again. It should be noted, also, that Doyle’s claim that term limits are the “norm” is inaccurate, as less than half the states in the U.S. currently limit terms.

2 Amer, Mildred, “Membership of the 111th Congress: A Profile,” Congressional Research Service Report R40086.

3 The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), “New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout in 2008 Election,” April 28, 2009.

4 Ibid.

5 Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, “Wisconsin Citizen Survey 2007,” Volume 20, No. 10.

6Basham, Patrick, “Defining Democracy Down: Explaining the Campaign to Repeal Term Limits,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis #490, September 30, 2003.

7 Wisconsin Department of Administration Office of Executive Budget and Finance, Fiscal Estimate to 2001 Assembly Bill 66.

8 Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, “2007-08 Committee Contributions to Candidates and LCCs,” and “2005-06 Committee Contributions to Candidates and LCCs.”

9 Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, “Wisconsin Citizen Survey 2007,” Volume 20, No. 10.

10 Chandler, Richard, “Limiting Government Spending in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, September 2004, Vol. 17, No. 5.

11 Schneider, Christian, “The State Budget Deficit: A Self-Inflicted Wound,” Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, February 1, 2009, Vol 22, No. 2.

12 An October, 2002, state general obligation bond issue received a AA rating from Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, Aa3 from Moody’s Investors Services, and AA by Fitch Ratings. Subsequently, in March 2004, Fitch Ratings downgraded the state’s general obligation debt to a AA- rating. This was a reduction from 1981, when the state’s bond rating was reduced from AAA to AA+ by Standard & Poor’s, and in 1982, when the state’s bond rating was changed from Aaa to Aa by Moody’s Investors Service.

13 Legislative Fiscal Bureau Informational Paper #74, “State Level Debt Issuance,” January 2009.

14 Moncrief, Gary F., Niemi, Richard G., and Powell, Lynda W., “Time, Term Limits and Turnover: Trends in Membership Stability in U.S. State Legislatures,” Legislative Studies Quarterly, XXIX, 3, August 2004.

15 Ibid.

16 This author.

17 Milwaukee Public Television, “4th Street Forum: Wisconsin Politics – Moving ‘Forward’ in 2008?” September 25, 2008.

18 This list is taken from “Budget Includes Millions of Earmarks” by Stacy Forster and Patrick Marley of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 29, 2009.

19 The Legislature also employs the Legislative Audit Bureau and the Legislative Technology Services Bureau, but neither of these are utilized for research in the way the LFB, LRB, and Legislative Council are.

20 Legislative Fiscal Bureau, “2009-11 Summary of Governor’s Budget Recommendations (AB 75).”

21 In the 2009-11 Legislature, 16 of the 18 Senate Democrats chair committees. The two that do not, state Sens. Judy Robson and Dave Hansen, both serve on the powerful Joint Finance Committee. The Assembly has 38 different committees, each chaired by an Assembly Democrat – of which there are currently 52.

22 Legislative Reference Bureau, “Redistricting: Why Legislative Districts Are Redrawn, How It Is Done, and by Whom,” September 2005.

23 Basham, p. 2.

24 Fund, John, “Making the Case for Term Limits,” Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1990.

25 Will, George F., “Restoration: Congress, Term Limits, and the Recovery of Deliberative Democracy,” Free Press, 1992.

26 Carey, John M., Niemi, Richard G., Powell, Lynda W., and Moncrief, Gary F., “The Effects of Term Limits on State Legislatures: A New Survey of the 50 States,” Legislative Studies Quarterly, XXXI, February 2006.

27 Ibid.

28 Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance, “Wisconsin’s General Fund Deficit Grows 13.7% to $2.44 Billion,” January 2, 2008.

29 Bowser, Jennifer Drage, Chi, Keon S., and Little, Thomas H., “Coping With Term Limits: A Practical Guide,” National Conference of State Legislatures, August 2006.