Vol. 25, No. 3

Most of 2011 saw tens of thousands of government union activists and supporters swarming around the Wisconsin State Capitol chanting, “Recall Walker!” and “This is what democracy looks like!” Organized labor was reacting to a new law proposed by Republican Gov. Scott Walker that required greater health care and pension contributions from state and local government workers, and that eliminated collective bargaining for every issue but base pay. Further, Walker’s law eliminated compulsory union membership for government workers, threatening the public sector unions’ ability to collect dues.

Unions and their supporters immediately turned to the state Constitution to exact their revenge. In 1926, voters approved a change to the Wisconsin Constitution that provided for the recall of state officials if a petitioner could gather 25 percent of the signatures cast in the previous gubernatorial election for the relevant district. In Wisconsin’s history, only two state elected officials had been successfully recalled. Nationally, only two governors have ever been recalled from office.

But in 2011, nine state senators faced recall elections (six Republicans, three Democrats). In 2012, four more Republican Walker-supporting state senators are scheduled to face recalls, as are Gov. Walker and Lt. Gov. Rebecca Kleefisch.

Recall supporters defended the sudden use of recalls as simply part of the democratic process. “The exercise of the constitutionally guaranteed right to force a recall election is a just and proper tool to force accountability upon those elected officials who act as if there is none,” the Democratic Party of Wisconsin explained on its website.

Recall supporters maintained that Gov. Walker’s action threw out 50 years of settled state law in essentially repealing collective bargaining. This might be true, but a review of history shows that the current effort to recall Gov. Walker is not at all in line with what the progressives intended when they championed the recall amendment 85 years ago. Documents and press accounts from the time indicate that the current use of the recall is far from what the original drafters envisioned.

The recall amendment began in the early 1900s as part of a slate of progressive “good government” reforms meant to decrease the role of special interests on the political process. Progressives believed the recall put more power in the hands of the people, allowing voters to remove corrupt elected officials. Further, they believed the recall mechanism was a way to purge the political process of the influence of money.

But as recent recall elections have demonstrated, the effect of the recall amendment has been the exact opposite. Additionally, the recall provision’s original supporters never intended it to be used as it has been in the past two years.

For example:

- The amendment’s supporters never could have envisioned that most state elected office terms would be extended to four years. When the recall amendment passed in 1926, all state officials except state senators had two-year terms. For the same reason that current two-year term Assembly representatives are not the subject of recall attempts, it wouldn’t have made sense to hold a recall election against a governor in May when he was up for election in November.

Terms for governors, lieutenant governors, attorneys general, and other offices weren’t extended to four years until 1967, when voters amended the state Constitution, thereby making those offices plausibly eligible for recalls. Yet in 1967, there was no public recognition or discussion that those offices could now be recalled; the process had never been used, and there is no evidence it was included in the debate. (The primary reason given at the time for extending terms to four years was that it would lessen the role of money in the process, since state officials would have to campaign half as much.)

Thus, without anyone realizing it, the recall was now an option for offices other than state senators and judges. This would have even been a surprise to 1926 recall proponents, who argued that the process would rarely be used. In fact, virtually all the public discussion surrounding adoption of the recall centered around its effect on an independent judiciary, not on elected officials. The recall’s primary opponents were lawyers’ organizations fearful that judges would be removed from office by special interests after issuing unpopular rulings.

- At the time the recall amendment was adopted, supporters believed the threat of recall would keep elected officials representative of the people. As the argument went, officials would be more responsive to the public than to special interests if their constituents could pull them out of office for corruption. Numerous progressives argued recalls would aid in keeping the influence of money out of politics.

The recent rounds of recall elections have demonstrated this to be the exact opposite of what eventually happened. Moneyed interests are now able, through spending and technology, to force a recall election of any elected official they wish for virtually any reason they deem acceptable. The recall elections have generated significant political spending by both sides.

It could be argued that elected officials have become less answerable to their constituents; they are increasingly dependent on groups that can use Facebook, Twitter, and Excel databases to threaten and cajole them into supporting their ideological agendas.

- While their arguments held for nearly 100 years, the recall’s original supporters’ contention that it would be a rarely used tool is no longer true. In 1911, collecting enough signatures to force a recall was a nearly insurmountable chore; few people would likely even know a recall effort was under way unless they heard about it from a neighbor.

The original proponents of the recall amendment could not have possibly anticipated a day in which electronic communications would make recalls so easy to conduct. In fact, one of their primary arguments was that collecting 25% of the electorate’s signatures was a high enough threshold to guarantee it would only be used in the most extreme cases.

But in 2011, this “extreme” case standard applied to six Republican state senators who supported Gov. Walker’s collective bargaining plan. Even more telling were the three recall elections held against Senate Democrats, organized largely as retribution for their efforts to recall Republicans.And while the stated purpose for recalling the six Republican state senators was the erosion of their “collective bargaining rights,” at no point during the recall elections did candidates or their supporters run television or radio ads mentioning the collective bargaining issue. Presumably, if Republican senators had done something so objectionable as to warrant recall, one would think it would be worth mentioning in the course of the campaign.

- Thus, the issue that ostensibly led people to support the recall (collective bargaining) melted into the background. The recall elections became just another campaign—effectively an election do-over. It’s easy to see how the political world could use the recall as a device to ensure perpetual elections.

This process has already begun, with conservative groups threatening the recall of two state senators over their votes on a bill to create a new iron ore mine in Northern Wisconsin. Recalls are no longer tools to root out corruption or the influence of money, but to remove state officials over differences on policy.

This report recounts the history of the recall amendment in Wisconsin and explains how utilization of the recall in practice diverts substantially from the original intent of the provision’s drafters.

The First Attempt: 1911

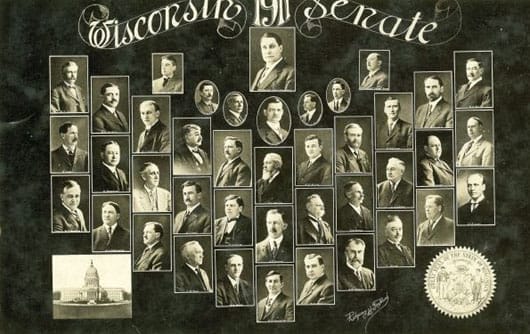

Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society

Advocates of greater government influence and regulation experienced a golden age both in Wisconsin and nationwide as the 20th century began. The Socialists began emerging as a force to be reckoned with; in 1904, Milwaukee elected its first slate of Socialist aldermen and county supervisors. In 1910, Socialist Emil Seidel would be elected mayor of Milwaukee.

In 1910, progressive Republicans were also entering their golden era. The 1909 “Insurgent” revolt against President William Howard Taft and Republicans in Congress catapulted Wisconsin Sen. Robert M. La Follette Sr. into national prominence, leading to formation of the National Progressive Republican League and, eventually, the Progressive Party.

In Wisconsin, progressive Republicans were being pushed further to the left by pro-government interest groups such as the Wisconsin State Federation of Labor (the socioeconomic arm of the Socialist Party) and the Wisconsin Society of Equity. Other groups of state government employees lobbied heavily for more government intervention, including numerous directors and staff members of state agencies, bureaus, and commissions: the Bureau of Labor and Industrial Statistics, the Department of Public Instruction, the Free Library Commission, the Board of Control, the Tax Commission, the Railroad Commission, the Dairy Food Commission, the State Historical Society, the Insurance Commission, the Board of Health, the Board of Agriculture, and others.1 Most of these groups’ directors and staff members had been appointed by progressive Republican governors, and therefore usually shared the governor’s more expansive view of government. Even more radical departures in government intervention emanated from the University of Wisconsin, including President Charles R. Van Hise and many of the faculty in the social sciences, humanities, agricultural extension, and engineering.2

The personal popularity of La Follette, coupled with the help of these entrenched groups, swept more progressives into office in the 1910 elections. This included progressive Republican Gov. Francis E. McGovern, who won with 52 percent of the vote. (Progressive Democrat Adolph Schmitz received 35 percent, while Socialist William A. Jacobs garnered 13 percent.)

McGovern, a tough district attorney from Milwaukee, built his reputation by rooting out corruption in city government. Though he and La Follette rarely disagreed on specific policy items, there was often friction between the two based on legislative priorities; McGovern was interested in urban, industrial reform, while La Follette thought electoral reform should be the governor’s primary emphasis.3

In the state Senate, a mix of socialists and progressives ensured McGovern the support of 27 out of the possible 33 senators. The Assembly was a slightly more mixed bag, as it consisted of 59 Republicans, 29 Democrats, and 12 Social Democrats. McGovern’s support in the Assembly was largely dependent on how many Republicans followed his agenda. He often relied on the help of the Democrats and Socialists to pass legislation. Seventy-five of the 133 legislators in the 1911 legislature were in their first term, having been elected in the 1910 progressive wave.

On January 12, 1911, Gov. McGovern issued his first address to the new legislature. In it, he laid out his progressive vision for Wisconsin, including his desire for a primary election law, an effective corrupt practices act, a workmen’s compensation law, an income tax, and better protection of environmental resources.

In addition, McGovern urged passage of three constitutional amendments that he argued would “keep the government really representative of the people.” He urged passage of constitutional changes that would allow for initiative, referendum, and recall. “They are closely related to each other, have a common object, and embody really but one idea—that of placing the people in actual control of public affairs,” he said in his address.

McGovern most strongly urged passage of the initiative process, which would allow groups of citizens to propose legislation and have it put to a vote statewide. “The people can be trusted to act prudently in governmental affairs in every case where they are in possession of information necessary to enable them to form intelligent judgments,” he argued.

Yet McGovern was much more skeptical of the recall process, while still supporting it. He claimed the recall “will be more restricted in its operation,” as it offered “an extension of the power of impeachment, with the people themselves as the tribunal.” He predicted, given the severe nature of the recall, it would be sparsely utilized, saying, “More drastic in its effects, and therefore less likely to be frequently employed, a higher percentage of the voters interested should be required to sustain a petition for the recall of a public officer than in the case of either the initiative or referendum.”

McGovern, like other progressives, believed the recall was a way of cleansing money from politics:

“Lavish expenditure of money through political channels for the purpose of influencing elections is a debauching and corrupting influence which has grown in prominence and baleful significance with each succeeding campaign. In any form this practice is demoralizing; but it becomes intolerable when it reaches the point of lawlessness and extravagance. Repeatedly single candidates and political committees have expended vast sums of money, sometimes more than $100,000, most of which was designedly employed to mislead the voters and befog the issues pending before them. Nothing more sinister in its political tendencies can be imagined.”4

McGovern was attempting to emulate other states that had already passed recall provisions. The first appearance of the recall in the US was in 1903, when the city of Los Angeles incorporated recall provisions into its charter. In 1908, Oregon became the first state to pass a law allowing the recall of state officials. Between 1908 and 1914, nine other states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Nevada, and Washington) adopted state recall provisions.5

Bob La Follette himself urged passage of the recall. Writing in La Follette’s Magazine, the US senator emphasized the infrequency with which the recall would be utilized:

“Through the initiative, referendum, and recall the people in any emergency can absolutely control. The initiative and referendum make it possible for them to demand a direct vote and repeal bad laws which have been enacted, or to enact by direct vote good measures which their representatives refuse to consider. The recall enables the people to dismiss from public service those representatives who dishonor their commissions by betraying the public interest. These measures will prove so effective a check against unworthy representatives that it will rarely be found necessary to invoke them.”6

The Senate wasted no time in complying with McGovern’s wishes. One week after the governor’s address, Senate Joint Resolution 9 was introduced by progressive Democratic Sen. Paul O. Husting of Fond du Lac. Husting would go on to represent Wisconsin in the US Senate for two years before he was shot to death by his brother Gustave in a duck hunting accident on Rush Lake. (Husting’s death would have national ramifications, as it would flip control of the US Senate to Republicans.)

Husting’s initial recall amendment authorized the recall of “every public officer in the state of Wisconsin holding an elective office, either by election or appointment.” According to the proposed amendment, one had to be a qualified elector to sign a petition, and between 30 percent and 50 percent of the number of electors in the official’s last election had to sign in order for a petition to be valid.

Yet when the resolution reached the Senate Judiciary Committee on April 14, it encountered opposition from senators who were concerned that the recall also applied to judges. A number of Husting’s colleagues were worried that the Social Democrats would use the recall process as a partisan tool to remove anti-labor judges. In order to allay the concerns of those predicting a Socialist judicial takeover, the committee offered an amendment to Husting’s resolution to exempt “judicial officers.”

However, when the resolution came to the floor of the Senate on April 19, some members were not comfortable with exempting judges from the threat of recall. Sen. Winfield Gaylord of Milwaukee moved to strike the exemption, but his motion was rejected. When the committee amendment providing for the judicial exemption came to a vote by the full Senate, it passed by a slim 15-to-12 vote (six senators were not present.) Husting voted against the exemption, but supported the full resolution after the amendment was added, and SJR 9 passed the full Senate by a 20-7 vote. Five conservative Republicans (“Stalwarts”), and two conservative Democrats opposed it.

The resolution faced fewer hurdles in the Assembly, where it passed by a 64-1 vote after a technical amendment was added. The full resolution as passed by both houses was enrolled on June 2, 1911.

The 1911 Legislature would earn a reputation as one of the busiest in state history. By mid-February, one month into the session, over 900 Assembly bills and 375 Senate bills had been introduced.7 Measures passing the 1911 Legislature included the nation’s first income tax, a new worker’s compensation act, and bills authorizing initiative and referendum processes. (Ironically, in 1911, the legislature also enacted the first pension program for teachers.)

Yet by the time the 1913 legislature took office, a backlash against Progressivism had taken hold. The leftward lurch of the 1911 legislature drove moderates to the Stalwarts, the conservative wing of the Republican Party. Progressive Republicans and Social Democrats began to fracture over partisan electoral issues, leaving the Legislature in disarray. Both of Wisconsin’s US senators fled progressivism in favor of the Stalwarts, and a bitter fight between McGovern and La Follette over “Fighting Bob’s” presidential ambition further segmented progressives.

At the beginning of the 1913 session, McGovern called on the Legislature to pass second consideration of the recall, referendum, and initiative constitutional amendments and send them to the voters for ratification. On Feb. 11, Husting once again introduced his recall resolution, this time numbered Senate Joint Resolution 18. In the 1913 session, it passed the Senate by a 26-to-1 vote and the Assembly by a vote of 72-to-17.

Yet in November 1914, voters were still in a very dyspeptic mood about progressives. All 10 of the constitutional amendments on the ballot in 1914 went down to defeat. Wisconsin voters rejected the recall by a 64-to-36 percent margin (144,386 to 81,628), and voted down the initiative and referendum amendment by a similar 63-to-37 percent margin. (148,536 to 84,934). Ironically, Husting himself would be elected to the US Senate on the same day, by a razor-thin 0.32% margin over Gov. Francis McGovern.

1923: The Progressives Return

After a tumultuous decade that saw progressive leader Sen. Robert M. La Follette Sr. become a polarizing figure statewide, progressivism began to enjoy a renaissance in the early 1920s.

In the late teens, La Follette’s anti-World War I stance earned him virulent opposition from large swaths of the Wisconsin public. Even former allies like progressive Republican Rep. Irvine Lenroot opted against defending La Follette when he was charged with anti-Americanism.

In 1918, Lenroot sought the US Senate seat left vacant by Paul Husting’s death. An angry La Follette vowed revenge against Lenroot for his lack of support, recruiting James Thompson to run for the seat. The fight was ugly and bitter, and it further fractured progressives. Lenroot would go on to win narrowly by cobbling together the support of progressive Scandinavians who disagreed with La Follette on the war.8

By 1920, Democrats had all but vanished from the Wisconsin political landscape. The public was weary of the war and punished the party of Woodrow Wilson for involving the US in the long conflict. (Wilson also had some less-than-flattering things to say about ethnic Americans, which didn’t endear him to the German-heavy Wisconsin population.) Between 1923 and 1925, Democrats had one member of the Assembly, and between 1923 and 1930, they had no members of the state Senate.

With one party dominating Wisconsin politics, the major battles took place within the progressive and stalwart wings of the Republican Party. And in 1920, progressives won a big battle with the election of former La Follette ally John J. Blaine to the governorship. (In 1914, Blaine had been talked into running for governor by La Follette to settle another vendetta; by 1920 La Follette had deserted him.)

The progressive resurgence continued in 1922, with the re-election of Bob La Follette to the US Senate. Once reviled across the state, La Follette crushed his Republican primary opponent, garnering 72 percent of the vote. Democrats, unable to recruit a serious candidate, ran Jessie J. Hooper, a liberal woman. La Follette defeated her with 80 percent of the vote.

As Progressivism grew in the state Legislature, some of the old “clean government” initiatives from 1911 began to return. Among these was the recall constitutional amendment.

On Valentine’s Day 1923, a new recall amendment was introduced by progressive Republican Sen. Henry Huber, a native Pennsylvanian and longtime La Follette loyalist. (Huber was the author of the Huber Law, which allowed prisoners to do manual labor during the day.) Huber’s resolution, 1923 Senate Joint Resolution 39, was amended once, passed the Senate by a 17-12 vote on March 21, 1923, then passed the Assembly by 60-10 vote on April 9 to complete first consideration.

Huber’s new recall procedure, as passed, was significantly different from the version voters defeated in 1914. The new recall procedure required signatures from individuals equal to 25 percent of votes cast in the most recent gubernatorial election to force a recall election. (Huber’s first draft required petition signers to be “qualified electors;” the resolution was amended to simply say “electors,” meaning anyone of age could sign.)

Petitioners had to wait one year after the official’s term first commenced, and could not attempt to recall an official more than once per term. In doing so, Huber limited the recall, in practice, to officials who had terms longer than two years; at the time, that meant only state senators and judges.

In November 1924, riding “Fighting Bob’s” coattails as he ran unsuccessfully for president (garnering 17 percent of the vote nationally), Blaine earned his third two-year term as governor. Blaine’s lieutenant governor, George Comings, decided to run against Blaine in the Republican primary in 1924, so Sen. Henry Huber ascended to the lieutenant governorship.

With Huber having been elected lieutenant governor, ownership of the recall resolution was passed on to Republican Max W. Heck of Racine, who introduced it on January 20, 1925. The resolution, 1925 Senate Joint Resolution 12, moved quickly through the legislative process. It passed the Senate by a 22-to-8 vote on Feb. 12, 1925, then passed the Assembly by a 70-to-22 vote on February 27. Several months later, on June 18, Sen. Robert M. La Follette Sr. would die of cardiovascular disease.

1926: The Public Votes

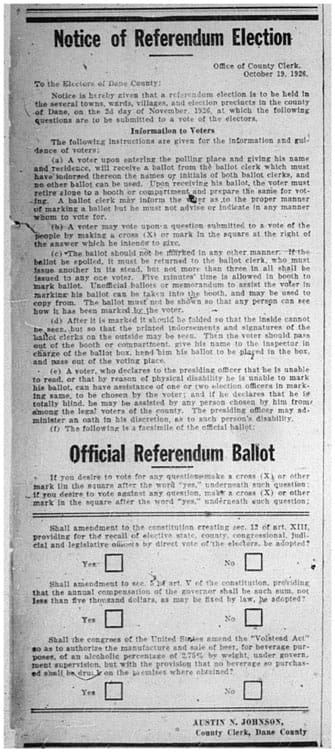

After passing two successive legislatures, the recall constitutional amendment was scheduled for a vote before the public on Tuesday, Nov. 2, 1926. On the same day, Gov. Blaine sought the US Senate seat held by Irvine Lenroot. Progressive Republican Secretary of State Fred Zimmerman sought the governorship, but was opposed by pro-La Follette Republicans for his failure to support La Follette’s presidential run. The Nov. 2 ballot also hosted a referendum on whether Wisconsin brewers should be allowed to violate Prohibition and brew 2.75 percent alcohol beer.

With all this action at the top of the ticket, the recall amendment went virtually unnoticed by the public or the media until just days before the election. The referendums for beer, for the recall, and for setting the governor’s salary at $5,000 made up the so-called “Pink Ballot” that was handed to electors separately.

In late October 1926, Manitowoc attorney I.J. Nash, the former Wisconsin reviser of statutes, wrote a prescient commentary urging Wisconsinites to reject the recall amendment. (Nash’s editorial, originally written for the Manitowoc Times, was reprinted in the Milwaukee Journal on Oct. 28.) Such a constitutional provision would make Wisconsin the “laughingstock of the country,” he wrote, adding that a recall proceeding is “slow, conducted with passion, expensive, sets neighbor against neighbor, is unaccompanied by sworn or other competent evidence, and convinces few that justice has been served.”9

In fact, it was never expected that the recall amendment would affect most state elected officials. As explained by former Supreme Court Justice Burr W. Jones in an Oct. 29 Wisconsin State Journal editorial:

“The amendment proposes a method of recalling state and county officers by petition and special election. It cannot be put into effect until the first year of an official term has expired. The further time necessary to put the recall machinery in motion would run well into the second year and close to the next regular primary and election. It would be impractical, therefore, and even absurd in some cases, to apply the recall plan to short-term officers.”

As mentioned, in 1926, governors, lieutenant governors, and attorneys general had two-year terms. The Wisconsin Constitution wasn’t amended to allow four-year terms for executive positions until 41 years later. Thus, the idea that a governor would be recalled under the new constitutional provision wasn’t even considered. Jones continued:

“Since most of our county and state officers hold for only two years, it must be apparent that the amendment is aimed at those officers who hold for longer terms. These are our judicial officers—our judges. The amendment would in practice affect few others.”10

Jones would go on to explain the effect the threat of recall would pose over judges, calling it the Sword of Damocles over the head of the judiciary.11

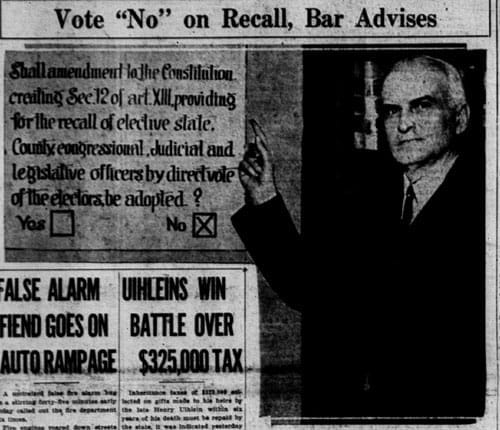

Due to its effect on the judiciary, the recall amendment was also opposed by the state’s major lawyer organizations, the State Bar of Wisconsin and the Milwaukee Lawyer’s Club. At an Oct. 25 meeting in a circuit court judge’s chambers, an estimated 200 attendees listened to attorneys assail the recall amendment. Speakers said the threat of recall would “destroy the independence of the judiciary and the impartial administration of justice, depriving all classes of the community of the protection now afforded by such independence, and replacing free exercise of the judicial function with the passing whim, passion, or prejudice of the populace.”12

One of these lawyer groups, calling itself the Citizens’ Committee in the Interest of Good Government, paid $369 for a half-page ad in the Milwaukee Sentinel to urge voters to “Keep the Courts Out of Politics.”

Attorneys weren’t the only ones actively against the recall amendment; opponents also got some help from a higher power. On Oct. 31, 1926, Milwaukee Catholic Archbishop Sebastian G. Messmer spoke out against the recall amendment. In an interview with the Milwaukee Sentinel, Messmer expressed concern about the capriciousness of a recall effort. “The very least that might be required of any minority group demanding the recall of an official or judge elected by a majority is that they give some reason for the action and that they be required by law to state that reason. It appears to be unfair to ask the recall of an elected public servant for no reason whatsoever,” said Messmer.

The Archbishop continued:

“Our judges are not elected for life, and if voters do not like the decisions made in the courts, they have their recourse at the polls or in impeachment proceedings before the legislature. They can put any man out when he comes up for re-election. . . .

After all, I believe the great masses of the people are not in a position to decide whether a decision is right or wrong. They must necessarily obtain their information from newspapers, for it would be impossible for all to listen to the evidence and testimony in a trial. And it is a principle of law that cases must be decided on all of the testimony and all of the evidence, and not upon sentiment.”13

The Milwaukee Journal editorialized against the amendment, arguing a judge shouldn’t be thrown out if he “offends a sentiment that a fourth of the voters rush to sign a petition.” The Journal mocked the contention by amendment supporters that recalls weren’t so bad because they would hardly ever be used. “A fine reason surely!” scoffed the editorial, adding, “If the recall is needed, it ought to be easy to use—not so hard that only wealthy interests or organizations which have piled up large funds for political purposes can employ it.”14

The Milwaukee Sentinel, which had traditionally been antagonistic to progressive causes, turned defeat of the amendment into an organizational mission. For days, the Sentinel ran headlines such as “Voters’ Lethargy May Thrust Evils of Recall on State,” (Nov. 1), and “Vote ‘No’ on Recall, Bar Advises,” complete with a stern photo of Milwaukee Bar Association president Frank T. Boesel admonishing readers to check the right box on their ballots: (Oct. 28)

The day before the election, the Sentinel ran an editorial calling the amendment “sinister” and “insidious,” and warning readers that the amendment affected the welfare of the state more “than any other that has ever confronted the voters in many years, if ever.” On Election Day, the Sentinel’s publisher, A.C. Backus, ran a banner headline reading “Vote ‘No’ on Pink Ballot Number One Today!” The headline was accompanied by a short explanation that called the recall amendment “one of the most pernicious and destructive amendments ever brought before the voters of the state.”

The amendment, however, did have supporters. The Wisconsin State Journal, while opposing recalls as they applied to the judiciary, supported the idea of using recalls in the case of “executive officials,” as its editors believed any recall of a governor would be purely symbolic. “Its use as to these, we believe, is in its potentiality more largely than in its practice, because the frequency of our elections of administrative officers gives the public the whip hand over them in any case, and so the recall as it affects them serves more than anything else as an admonition,” they editorialized.15

The State Journal also ran a column by newly minted US Sen. Robert M. La Follette Jr., who urged passage of the amendment. La Follette mentioned that 10 states had passed similar recall amendments, and that it contained ample safeguards to ensure fairness—such as the provision that required a one-year wait once an elected official or judge had taken office.16

The State Journal also ran a weekly column called “News of Interest to Madison Labor,” in which the author, Leo Straus, urged passage. “The Wisconsin Federation of Labor has issued an appeal to the workers of the state to vote on Tuesday,” Straus began. “It also recommends the favorable ballot on the recall,” as well as the brewing referendum, he added. “While labor in this state has never definitely committed itself to any political party, it has on several occasions entered the ring and battled for the late Sen. La Follette,” Straus clarified.17

On election night, while progressives were being swept into office by large margins, the recall amendment stalled. The first post-election front page of the Milwaukee Journal trumpeted “Beer Wins 2 to 1; Recall Doubtful.”

Yet as more votes came in, the recall amendment pulled closer and closer to even. Each successive headline in the Milwaukee Sentinel showed creeping doubt that it had been defeated:

“Recall Measure Hangs in Balance in Early Returns”

“Fate of Recall Hangs in Balance in Late Returns”

“Amendment for Recall is Facing Stiff Struggle”

“Recall Amendment Winning in Late Vote”

Then, finally, the following Thursday, Nov. 4:

“Recall Held Winner Upon Late Returns”

When all the votes were cast, the recall amendment had won by 4,743 votes, or with a slim 50.6 percent of the electorate. The amendment underperformed both Blaine and Zimmerman, as voters were more skeptical of the progressive-backed recall amendment than they were of the progressive candidates.

Puzzlingly, the amendment had lost in Dane County, the heart of the progressive movement (8,803 to 7,590). But, as the Sentinel pointed out in its summary of the final vote, the amendment won Milwaukee by 12,000 votes, “aided by Socialists,” it was quick to point out. “Urban communities were inclined to favor adoption of the measure, while the tendency in rural and conservative districts was to reject it,” it opined. (Milwaukee went on to support the beer referendum by a margin of seven to one. Prohibition ended on April 7, 1933, and more than 100,000 people celebrated in the streets of Milwaukee.)

The Recall Amendment in Practice

As expected, the recall tool was used sparingly following passage in 1926. Since senators were the only state officials with four-year terms, they became the only plausible targets of recall. In 1932, Republican State Sen. Otto Mueller became the first state official to be subjected to a recall election. Mueller was recalled by La Follette progressives as a part of a larger effort to remove state officials who opposed a tax bill submitted by Gov. Phillip La Follette.

Yet Mueller won his recall election against Roland Kannenberg by a margin of 14,160 to 8,541 and returned to the Senate. Petitions were also taken out against Sens. Bernhard Gettleman, Eugene Clifford, and William D. Carroll, but an insufficient number of signatures was collected.

In 1954, a group calling itself “Joe Must Go” attempted to recall Republican US Sen. Joseph McCarthy. The group garnered national attention, but fell short of the required number of signatures needed. To add insult to injury, leaders of “Joe Must Go” were charged with 21 counts of violating state law by making $8,000 in illegal payments to state and local elected officials.18

1967: Changing Term Length

In 1967, Wisconsin voters approved a change to the state constitution that granted the governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, attorney general, and state treasurer four-year terms, and merged the campaigns of governor and lieutenant governor into a single ticket. In doing so, Wisconsin became the 40th state to grant its governor a four-year term, and only the seventh to merge the governor and lieutenant governor onto a single ticket. (The four-year term for governors and lieutenant governors passed with 63.5 percent of the vote.)

Proponents of four-year terms argued that two years was not enough time for governors to develop and implement effective policies. Further, they argued that four-year terms allowed governors a break from campaigning in order to focus on policy.

Opponents of the four-year term amendment claimed that two-year terms kept governors more in touch with the people they represented. Constant campaigning, they argued, was good; it forced elected officials to be accountable and responsive to the public. Perhaps most ironically, opponents argued that four-year terms would “make it harder to remove inept or corrupt officials.”19

There is no evidence found that in advance of 1967 the recall process was raised in considering moving to four-year terms. A successful recall of a state official had yet to take place; it simply was not conceivable at the time. On Jan. 4, 1967, the Milwaukee Sentinel editorialized in favor of four-year terms, but made no serious arguments for or against; it simply seemed like a common-sense reform.

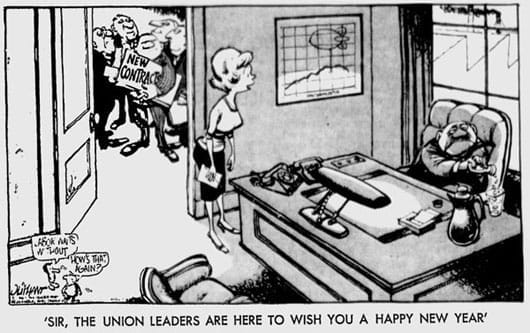

Auspiciously, adjacent to the Sentinel’s 1967 editorial in favor of four-year terms ran a cartoon warning of the union trouble that would one day come:

In 1996, 70 years after the recall amendment was passed, State Sen. George Petak became the first state elected official to be successfully recalled. Petak’s recall occurred after he reneged on a promise to his constituents that he would not vote to include Racine in the taxing jurisdiction for the new Milwaukee Brewers stadium. In 2003, State Sen. Gary George was recalled shortly before being sent to prison on corruption charges.

In 1997, a pro-life group tried to collect enough signatures to recall US Sens. Russ Feingold and Herb Kohl for their support of the partial-birth abortion medical procedure. The group fell about 50,000 signatures short.20

The Recall Today

In 2011, following passage of Gov. Walker’s collective bargaining reforms, organized labor announced recall efforts against six Republican state senators who had supported the new law. (The remaining senators were not eligible for recall, as they had not served the required one year in office.)

“The proposals and the policies that Republicans are pushing right now are not what they campaigned on, and they’re extreme,” the Democratic Party chair, Mike Tate, told The Washington Post. “Something needs to be done about it now. We’re happy to stand with citizens who are filing papers to recall these senators.”21

Over the course of the campaign, those supporting the recalls, including organized labor, spent an estimated $20 million to recall the GOP senators. On the other side, nearly as much was spent by and on behalf of the incumbents. Little of the pro-recall money was spent trying to convince the public of the righteousness of the unions’ collective bargaining position; instead, ads were run accusing the senators of cutting school funding, reducing health services funding, and giving tax breaks to big business.22 Someone wandering into Wisconsin from another state would have no idea what these senators did that warranted their recall from office.

It would seem a stretch to demonstrate that any of them had “dishonored their commissions by betraying the public interest,” (Bob La Follette’s standard for recall), for if they had, it might have been worth mentioning in the campaigns against them.

The recall was successful in unseating two senators. One Republican senator in a traditionally Democratic district lost, and another Republican senator lost after his extramarital affair with a 25-year old Capitol staffer was exposed. In all, four of the six Republicans survived, and Democrats failed to take control of the State Senate by one seat.

Yet 2011 was merely an appetizer to 2012, when the governor, lieutenant governor, and four more Republican state senators will be subject to recall elections. In a March interview, Gov. Scott Walker said he expects organized labor to spend between $70 million and $80 million against him in the recall election, a sign that the recall has exacerbated the presence of money in politics rather than ameliorated it.23 Walker himself is expected to spend tens of millions of dollars defending himself, as will groups opposing his recall.

It seems that the recall is about to become a regular feature of Wisconsin’s political landscape. In so many ways, the circumstances today could never have been envisioned when the Constitution was amended to allow recalls. Technological developments have made identifying and targeting potential recall petition signers as easy as pressing a button. The Democratic Party of Wisconsin announced that it had the names of 200,000 potential signatures in a database before the recall petition circulation process even began in November 2011. (Slightly over 900,000 signatures, well over the 540,000 needed to force a Walker recall, were collected.) Furthermore, much of the money supporting and opposing the recall is coming from out of state.24

During the debate of the recall amendment, progressives argued that the recall was appropriate because it would rarely be used. That argument is now forever moot.

Take, for example the pending recall election against Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, who in his last three elections has received 68 percent, 97 percent (unopposed), and 69 percent of the vote in his district. It is difficult to find an elected official with more popular support among his constituents. Yet in Wisconsin in 2012, every Senate district has more than enough members of the opposite party to force a recall, and technology makes them easy to find and to mobilize. If a recall can be used against an elected official as popular in his district as Scott Fitzgerald, it can be used against anyone; and likely will, making Wisconsin a state of perpetual elections.

This is becoming evident, with the effort by conservative groups to recall two senators who, in March blocked passage of a bill to create an iron ore mine in northern Wisconsin. These recall efforts are based not on “corruption” or malfeasance in office, but simply a disagreement on a policy matter.

It appears that no longer will the recall be used judiciously, and increasingly, recalls will become the tool of special interests—whose influence Bob La Follette spent his entire career trying to reduce. Instead of keeping elected officials beholden to the people, recalls keep them beholden to a single moneyed interest group that can force their recall at any time. This is exactly the opposite of what the amendment intended to do.

As La Follette once said, “the supreme issue involving all others, is the encroachment of the powerful few upon the rights of the many.” The modern use of the recall demonstrates that to be true.

Endnotes

Buenker, John D., Ph.D., “Progressivism Triumphant: The 1911 Wisconsin Legislature,” The 2011-12 Wisconsin Blue Book.

Ibid.

Fowler, Robert Booth, Wisconsin Votes: An Electoral History, University of Wisconsin Press.

Message of Gov. Francis E. McGovern to the Wisconsin Legislature, Regular Session, Thursday, January 12, 1911.

Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau Brief No, 17, “Some Basic Facts About Recall With Particular Reference to Wisconsin,” June 1954.

La Follette, Robert M. Sr., La Follette’s Magazine, October 17, 1914.

Ibid.

Fowler, p. 124.

“Oppose Recall, Plea of Expert: Amendment Passage Would Make State Ridiculous, View,” Milwaukee Journal, October 28, 1926.

“Burr Jones Asks Defeat of Recall,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 29, 1926.

“Burr W. Jones Urges Recall be Defeated,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 26, 1926.

“Lawyers Unite Against Recall,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 26, 1926.

“Prelate Also Opposes Recall of Judges: Clergyman Calls Proposed Amendment ‘Dangerous Move that Threatens Stability of Courts,’ ” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 31, 1926.

“On, Wisconsin: The Recall,” Milwaukee Journal, October 31, 1926.

“Judicial Recall,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 29, 1926.

“La Follette, in Statement, Urges Support of Amendment and Election of Blaine,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 29, 1926.

Straus, Leo, “News of Interest to Madison Labor,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 31, 1926.

“Recall Group Charges Filed: 21 Count Information Given Gore; Claims Payments Illegal,” The Milwaukee Journal, July 10, 1954.

“Four-Year Statehouse Terms and Joint Ticket Adopted,” The Milwaukee Journal, April 6, 1967.

“Abortion Foes Fall Short in Bid to Force Recall Vote on Senators,” The Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1997.

“Breaking: Wisconsin Dems Throw Their Weight Behind Drive to Recall GOP Senators,” The Plum Line, March 2, 2011.

Gilbert, Craig, “The ad wars heat up in the Wisconsin recall campaigns,” JSOnline, July 17, 2011.

Carey, Nick, “Money flows into Wisconsin governor recall fight,” Reuters, February 16, 2012.

Ibid.