February 2010, Vol. 23, No. 2

By Joan Gucciardi

Executive Summary

The recent fiscal challenges facing Wisconsin state and local governments have caused a serious re-evaluation of all aspects of government spending. Yet, little attention has been given to the cost of providing pensions to public employees. In Wisconsin, nearly all public employees participate in the same pension system: the Wisconsin retirement system. In 2007 (the last year for which data is available) contributions to public pensions required $1.3 billion in taxpayer support.

This report is an initial attempt to highlight public employee pensions. We compared pension benefits across all salary ranges. Specifically, this report looks at public pensions in the context of pensions available to employees in the private sector. Of course, public sector employment differs from private sector employment in a number of ways. This study only examines differences in pensions between public and private sector employers. This is not intended to be a comprehensive comparison of compensation and benefits. It does not examine salaries or other benefits such as health insurance for workers or retirees. Only through such a comprehensive evaluation could an assessment be made as to the relative strengths and weaknesses of the public and private sector compensation.

This report highlights significant differences between public and private pensions in Wisconsin. Public employee pensions are marked by stability and provide employees with certainty in their retirement. The few changes that have been made to the WRS in recent years have served to enhance the benefits to employees. In addition, any review of the WRS must highlight the fact that nearly all of the contributions to the system are made by the employer. Overall, employees contribute less than one percent of the cost of their retirement.

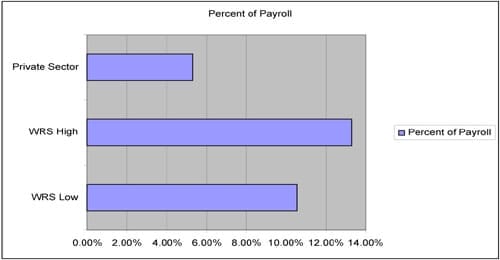

This stands in stark contrast to private sector pensions. As this report shows, private sector pensions have been subject to significant change. First, private employers have moved away from offering defined benefit pensions and have moved toward providing defined contribution pensions. In Wisconsin, 88% of employers offer defined contribution plans compared to just 8% that offer defined benefit plans – the kind that are offered by all government employers. Further, private sector pension contributions are significantly less than public sector pensions when measured as a percent of payroll, and the contributions as a percent of payroll have been declining. The average employer contribution for private sector plans is 5.3% of payroll, compared to the WRS, in which the employer contribution ranges between 10.55% and 13.3% of payroll.

Chart 1

Wisconsin Employer Pension Contribution As Percent of Payroll

Each one percent of payroll represents approximately $110 million. If public employer contributions were similar to private sector contributions, $577 – $880 million less would be required each year.

With respect to retirement benefits, the person retiring from a government job in Wisconsin is likely to see a higher monthly annuity than a retiree from the private sector. The table below compares a 25-year WRS employee to a private sector employee. It shows that a private sector employee earning $70,000 in the year before his/her retirement will receive somewhat comparable retirement income as his/her WRS counterpart earning $48,000 per year.

Table 1

Benefit Comparison

| WRS Employee | Private Sector Employee | |

| Annual Salary | $48,000 | $70,000 |

| Estimated Social Security | $1,536 | $1,781 |

| Estimated Retirement Benefit | $1,712 | $1,301 |

| Total Estimated Benefit | $3,248 | $3,082 |

The Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS) provides a guaranteed pension for employees who work for the state, its municipalities, and school districts, excluding City and County of Milwaukee employees. The maximum benefit for long-service employees ranges between 70% and 85% of final average earnings, depending on employment category.

For employees with at least 25 years of service, such benefits exceed the recommended replacement ratios established in a study by Georgia State University and Aon Consulting. A replacement ratio is a person’s gross income after retirement, divided by his or her gross income before retirement.

Example. An individual earns $60,000 per year before retirement. This individual retires and receives $45,000 in Social Security and other retirement income. This individual’s replacement ratio is 75% ($45,000 / $60,000).

The amount contributed to provide these benefits in 2007 was approximately $1.3 billion. Approximately 99½% of this amount was borne by the employers (the state, its municipalities, and school districts). For 2010, the projected contribution rate (as a percentage of payroll) ranged between 11.2% and 15.5%, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Contribution Rates for 2010 Expressed as a Percentage of Participant Payroll

Group | Percentage of Payroll |

| General Participants | 11.2% |

| Executives and Elected Officials | 11.9% |

| Protective Occupation with Social Security | 14.1% |

| Protective Occupation without Social Security | 15.5% |

Small and medium-sized private sector employers have generally moved away from defined benefit plans in favor of 401(k) plans. In such plans, the employer contribution is likely to be made only in the form of a matching contribution; e.g., 50% of the employee’s salary-deferral amount (i.e., the amount that the employee chooses to reduce his/her salary by) up to a maximum of 3% of payroll.

Company contributions (for private sector employers) made to defined contribution arrangements averaged 4.7% of payroll in 2006. Such contributions were highest in profit sharing plans (9.2% of payroll) and lowest in 401(k) plans (3.0% of payroll).

Benefits provided under the WRS plan are far more generous than private sector defined benefit plans. Private sector defined benefit plans, in turn, are a minority of the plans offered by private sector employers. Although it is not possible to make an apples-to-apples comparison,

in general, benefits of a private sector defined contribution plan are not nearly as generous as that of a defined benefit plan.

A defined benefit plan is a cost-effective method of delivering benefits to long-service employees. Defined contribution plans generally provide for age-neutral contributions, which generally favor younger employees over older, long-service employees. Defined benefit plans provide similar levels of benefits at normal retirement age to employees, regardless of their age at the time of employment, if they have worked the same number of years.

The adequacy of the benefits should be measured against the cost. In the case of the WRS plan, the benefits for long-service employees (25 or more years of service) are more than adequate to meet such employees’ retirement needs.

Background

The Wisconsin Policy Research Institute has requested that Summit Benefit & Actuarial Services, Inc. prepare a study of public and private pension plans in the state of Wisconsin and in the United States. This is not a comprehensive study of public and private benefits but rather addresses only the pension benefit systems of the public and private sectors in Wisconsin.

Defined Benefit and Defined Contribution Plans

Brief History of Defined Benefit and Defined Contribution Plans. Defined benefit plans have been around for over 125 years in the private sector. American Express Company, a railroad freight forwarder, introduced the first pension plan in 1875 in an effort to promote a stable, career-oriented workforce. By 1920, pension plans had become a normal part of the employee benefit package for larger employers. Participation in defined benefit plans increased significantly following World War II, reaching 45% of the workforce by 1970. Some well-publicized failures (notably Studebaker) resulted in the passage of the Employee Retirement Security Act of 1974 (ERISA).

Defined contribution plans have not been around for nearly as long. Before 1978, many companies had profit-sharing plans or other types of deferred compensation plans. Some were called thrift plans, where employees had the opportunity to contribute on a post-tax basis and the companies made matching contributions. Permanent provisions were added to the Internal Revenue Code via Section 401(k), effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 1979. The floodgates were opened as employers responded in 1982 with the adoption of new 401(k) plans and the conversion of existing thrift plans from after-tax contributions to pre-tax contributions.

How Defined Contribution Plans Work. In a defined contribution plan, amounts are paid into an individual account by employers and/or by employees. The contributions are then invested, and the returns on the investment (which may be positive or negative) are credited to the individual’s account. At retirement, the employee’s account is used to provide retirement benefits, sometimes through the purchase of an annuity, which then provides a guaranteed lifetime income. Most often, the defined contribution account is either paid out in a lump sum (and immediately taxable) or directly rolled into an individual retirement arrangement (IRA) to maintain the tax deferral.

Defined contribution plans have become widespread in recent years, and are now the dominant form of plan in the private sector in many countries. The number of defined benefit plans in the U.S. has been steadily declining as more and more employers see pension contributions as a large, volatile expense avoidable by disbanding the defined benefit plan and instead offering a defined contribution plan.

Money contributed can be either from employee salary deferrals or from employer contributions. The portability of defined contribution pensions is legally no different from the portability of defined benefit plans. However, many defined benefit plans do not allow a lump sum option; therefore, in those plans, portability is very limited.

However, because of the cost of administration and ease of determining the plan sponsor’s liability for defined contribution plans (you don’t need to pay an actuary to calculate the lump sum equivalent as you do for defined benefit plans), in practice, defined contribution plans have become generally portable.

How Defined Benefit Plans Work. In a typical defined benefit (DB) plan, employers promise to pay retirement benefits based on an employee’s period of service and final average salary. For example, a typical benefit formula for an employee is 2% times final average salary times years of service. Under this formula, an employee who works 20 years and retires with a final average salary of $40,000 would earn an annual benefit of $16,000 (20 X 2% X $40,000).

Eligibility for the benefit (i.e., vesting) usually requires employees to work for a minimum period of time, typically five years. Upon retirement, the benefit is provided as a series of monthly payments over the retiree’s lifetime (and the surviving spouse’s lifetime if this option is selected by the member, who, in return, receives a reduced benefit). Most public sector DB plans provide cost-of-living adjustments as protection against inflation. In addition, most public sector DB plans provide disability and pre-retirement death benefits.

Public sector DB plan benefits are financed by contributions from the employer (and most often from employees as well) and investment income. Employee contributions are usually established at a fixed rate of pay (e.g., 5%). Employer contributions are calculated so that, over the long run (40 years or more), annual contributions plus expected investment earnings are enough to pay the promised benefits plus administrative expenses.

The calculations are done by actuaries and designed to maintain employer contribution rates at a constant level percent of payroll, by smoothing short-term investment fluctuations and using other actuarial techniques. Plan assets are generally invested in professionally managed, broadly diversified portfolios, with investment fees paid by the plan or employer. Retirement benefits are paid from accumulated contributions and investment earnings.

For employers, a key advantage of DB plans is that investment earnings reduce future employer contributions. In other words, employer and employee contributions generate investment earnings that, in turn, are used to pay benefits that would otherwise have to be paid from future employer contributions.

A potential disadvantage of DB plans is that when investment earnings are less than expected, additional employer contributions are required. Certainly, with the market downturn of 2008 and early 2009, additional employer contributions will be required for most defined benefit plans in 2009 and 2010.

For employees, a key advantage of DB plans is that they provide secure and predictable retirement income over their lifetimes based on pre-retirement earnings. A key disadvantage is that employees who do not remain employed long enough to become vested often lose their DB plan benefits, although employee contributions are usually returned with interest.

How Defined Benefit and Defined Contribution Plans Differ. In a defined contribution plan, investment risk and investment rewards are assumed by each individual and not by the plan sponsor. In addition, DC participants do not necessarily purchase annuities with their savings upon retirement, and bear the risk of outliving their assets.

The “cost” of a defined contribution plan is readily calculated, but the ultimate retirement benefit from a defined contribution plan depends upon the account balance at the time an employee retires.

Despite the fact that the participant in a defined contribution plan typically has control over investment decisions, the plan sponsor retains a significant degree of fiduciary responsibility over investment of plan assets, including the selection of investment options and administrative providers.

Generally speaking, there are economic efficiencies of a DB plan versus a DC plan. The cost, of course, depends primarily on the level of the benefits provided. The major reasons for the economic efficiencies of DB plans:

- DB plans pool the longevity risks of large numbers of individuals. Thus, a DC plan participant will need to accumulate more dollars to pay the same lifetime benefits because he or she will need to assure that he or she never runs out of money.

- DB plans can take advantage of enhanced investment returns that come from a balanced portfolio over a long time period. A DC plan participant will generally move to more conservative investments as he or she ages, thus reducing the return credited to the retirement account.

- A Wyatt study has demonstrated that DB plans earn consistently higher rates of return due to professional management of assets as compared to individual investors for DC plans.

ESOPs and Other Private Sector Enhancers. The most common private sector enhancer is an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. The term “Employee Stock Ownership Plan” was first defined by federal legislation in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. In the Tax Act of 1978, ESOPs are defined as “. . . a technique of Corporate Finance. . ..” Thus, their purpose of benefiting both employees and the company has been clearly defined by Congress. From 1974 to date, it has been estimated that 20,000 companies have installed Employee Stock Ownership Plans. The total number of employees currently covered by ESOPs is about 11,000,000. However, many ESOPs existed prior to 1974, even though such plans were not defined by federal statute.

Although technically only in existence since 1974, the concept of Employee Stock Ownership Plans has been in the law since 1921 in the form of Stock Bonus Plans. Stock Bonus Plans, like Employee Stock Ownership Plans, are tax-exempt trusts that are designed to enable employees to own part or all of the company for which they work, without investing their own personal funds. The distinguishing feature of an ESOP is that, unlike a Stock Bonus Plan, it may engage in “leveraged” purchases of company stock. That is, an ESOP may acquire stock not only on a year-by-year basis, but also may borrow funds in order to purchase a block of stock.

According to a study performed by the National Center for Employee Ownership, the statistics indicate there are approximately 11,500 ESOP plans in 2006, which cover 10 million participants.

Benefit Provisions

The current plan for employees who work for the state, its municipalities, and school districts is a defined benefit plan. The plan has defined contribution elements, as explained below. Under the plan, eligible participants receive a monthly retirement benefit, based on their years of credited service and average compensation. We have highlighted the major provisions in the WRS, with more details in Appendix A.

Normal Retirement Benefit. The normal retirement benefit is the greater of two items:

- The Formula Benefit

- The Money Purchase Benefit

The Formula Benefit. The normal retirement benefit payable at normal retirement age is based on Final Average Earnings (FAE) and Creditable Service (CS) and depends on the employment category as shown in the table below:

Table 3

Benefit Multipliers

| Multiplier for Service Performed After 1999 | Multiplier for Service Performed Before 2000 | Group |

| 2.0% | 2.165% | Executive group, elected officials and protective occupation participants covered by Social Security |

| 2.5% | 2.665% | Protective occupation participants not covered by Social Security |

| 1.6% | 1.765% | All other participants |

The Money Purchase Benefit. A money purchase retirement benefit is calculated by multiplying the employee and employer deposits in the employee’s account by an actuarial money purchase factor based on the age when the annuity begins. The interest rate credited to the account will depend on whether the employee elects a fixed or variable fund. The table below shows sample rates for converting the accumulated employer and employee accounts to a monthly benefit.

Table 4

Money Purchase Conversion Factors at Various Ages

Age | Monthly Benefit Factor |

| 50 | .00530 |

| 55 | .00570 |

| 60 | .00625 |

| 65 | .00705 |

| 70 | .00822 |

Contribution Rates. The financial objective of the Wisconsin Retirement System is to “establish and receive contributions that will remain level from year to year and decade to decade.” The statute requires employee contributions as follows:

Table 5

Required Participant Contributions

Group | Rate (Percentage of Payroll) |

| General | 5.0% |

| Executives and Elected Officials | 5.5% |

| Protective Employees With Social Security | 6.0% |

| Protective Employees Without Social Security | 8.0% |

Employee Contributions. Although the employee contribution rates are set by statute, nearly all employers pick up the employee-required contributions. The statute specifically allows an employer to pay on behalf of an employee all or part of any employee-required contributions.

National Reference

Comparison of Wisconsin Retirement System to Other Wisconsin Defined Benefit Plans. It is difficult to compare the WRS plan to private sector defined benefit plans in Wisconsin because there are so few private sector defined benefit plans.

In fact, MRA-The Management Association stopped preparing their annual Retirement Plans Survey in 2000 due to the small number of MRA members who had defined benefit plans. By way of background, MRA is the largest employers’ association in the Midwest.

The following statistics are from the 1999/2000 Retirement Plans Survey. Four hundred and ninety Wisconsin and northern Illinois companies took part in the survey, and the breakdown by number of employees is shown below:

Table 6

1999/2000 MRA Survey: Size of Companies Participating

| Number of Employees | Percentage of Total Companies Responding to Survey |

| Over 500 | 6% |

| 250 – 500 | 6% |

| 100 – 249 | 19% |

| 50 – 99 | 25% |

| 1 – 49 | 44% |

Of the 490 companies that participated in the survey, 98% have some type of retirement plan. A relatively small portion of the 490 companies had a defined benefit plan – 16%. Of the 490 companies, 81% had some type of defined contribution plan, including profit sharing, 401(k), 403(b), ESOP, or SIMPLE IRA. Of those 16% (78 companies) that had defined benefit plans;

- 96% of the defined benefit plans were funded solely by the company.

- Contributions (as a % of payroll) ranged widely.

Table 7

1999/2000 MRA Survey: Defined Benefit Contributions as a Percentage of Payroll

| Contributions as a Percentage of Payroll | Percentage of Total |

| Less than 2% | 24% |

| 2% – 3.99% | 23% |

| 4% – 5.99% | 18% |

| 6% – 7.99% | 4% |

| 8% – 9.99% | 6% |

| 10% or more | 6% |

| No response | 18% |

(Note: The results may be somewhat skewed due to the impact of OBRA ’87, which provided a “funding holiday” for many defined benefit plans.)

It is interesting to note that the average employer contribution under WRS is at least 10% of payroll, while fewer than 25% of the private sector companies contributed more than 10% of payroll. Relatively few companies paid a subsidized early retirement benefit.

Table 8

Percent of Companies Offering Subsidized Early Retirement Benefits

Type of Subsidized Early Retirement Benefit | Percentage of Companies |

| Supplementary benefit paid until age 62 | 6% |

| Supplementary benefit paid until age 65 | 6% |

| No supplementary benefit | 46% |

| N/A | 43% |

Table 9

Normal Retirement Ages in Surveyed Companies

| Normal Retirement Age | Percentage of Companies |

| Age 62 | 6% |

| Age 65 | 92% |

| Other | 2% |

The normal retirement age in the survey defined benefit plans was generally age 65 as seen in Table 9.

Contrast this with the WRS plan, where employees with 30 years of service can retire with unreduced benefits as early as age 57. An experience study for 2003 through 2005 prepared by Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company for the WRS showed that the rate of retirement was significantly higher for ages younger than 65. The table below shows the percentage of individuals who are eligible to retire that opt to actually retire. For example, at age 58, 24.22% of male individuals who were eligible to retire actually did retire.

Table 10

General Male and Female Age-Based Retirement Experience

Age | Male Experience | Female Experience |

| 57 | 22.09% | 16.64% |

| 58 | 24.22% | 22.82% |

| 59 | 17.80% | 19.90% |

| 60 | 23.00% | 19.03% |

| 61 | 19.81% | 23.30% |

| 62 | 30.29% | 22.32% |

| 63 | 39.23% | 38.06% |

| 64 | 23.62% | 23.21% |

| 65 | 18.43% | 20.40% |

The pension formulas used by private employers are dominated by final average pay formulas, similar to the WRS plan as seen in Table 11:

Table 11

Types of Pension Formulas in Surveyed Companies

Type of Pension Formula | Percentage of Companies |

| Dollars Per Month Per Year of Service | 6% |

| Career Average | 6% |

| Final Average Pay | 65% |

| Other | 24% |

(Note: The “Other” category is likely cash balance plans.)

Some of the plans of Wisconsin employers are offset by Social Security. In other words, there is a formula benefit that is computed and then reduced by the estimated Social Security benefit (e.g. 50% of Final Average Pay reduced by 40% of the Primary Insurance Amount)

Table 12

Percentage of Companies Providing for Social Security Offset

Social Security Offset? | Percentage of Companies |

| Yes | 43% |

| No | 43% |

| Don’t Know/No Response | 14% |

More updated information on Wisconsin private sector plans was provided in several recent surveys provided to the author by MRA:

Table 13

MRA Surveys on Private Sector Retirement Plans

| Year | 2009/2010 | 2007/2008 | 2005/2006 |

| Number of Organizations Responding | 380 | 400 | 574 |

| Types of Plans Offered | |||

| None | 8.40% | 7.80% | 9.80% |

| 401(k), 403(b), or 457 plan | 88.70% | 88.50% | 83.80% |

| Defined Benefit | 8.20% | 8.50% | 10.30% |

| Profit Sharing without 401(k) feature | 12.40% | 8.00% | 12.90% |

| Other | 6.10% | 15.50% | 15.30% |

| Percent Contributed to Profit Sharing Plan | 34.90% | 35.50% | 54.40% |

| Average Employer Contribution as a Percentage of Payroll | 8.70% | 8.40% | Not Available |

| Average Maximum Percentage Matched for Companieswith 401(k) Plans | 5.30% | 5.50% | 6.90% |

Here are some observations on the survey information provided by MRA:

- The vast majority of companies (over 88% in 2009) offered 401(k) plans.

- The maximum match in recent years is slightly less than 5½% of pay; this assumes that the individual contributed at the level that qualified for the maximum match. This does not mean that the company contributed 5½% of pay for all eligible employees. The survey did not collect data on the amount or percentage of pay that companies contributed to the employer matching portion of the 401(k) plan.

- The data for the 2009/2010 survey was collected in 2008 and likely reflects the 2007 results. The author anticipates that the 2011/2012 survey will reflect a significant reduction in employer matching contributions and profit-sharing contributions.

- Only 8.2% of the employers surveyed provide a defined benefit plan. No information was collected to indicate whether such plans are currently accruing benefits or are frozen.

Comparison of National Data to WRS Plan. A survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and published in fall 2009, found the private sector workers have access to retirement benefits at the following rates:

Table 14

Percentage of Private Sector Employees with Access to Retirement Plans

Plan Type | Percent with Access |

| All Retirement Plans | 67% |

| Defined Benefit Plans | 22% |

| Defined Contribution Plans | 62% |

It is important to note that, while 62% of all employees have access to a defined contribution plan, the participation rate is significantly lower (closer to 50%) because many employees choose not to defer any portion of their salary in a 401(k) plan.

While BLS found that 22% of private sector workers are in a defined benefit plan, a much smaller percentage of companies actually offer defined benefit plans. This is due to the fact that it is primarily large companies that continue to offer defined benefit plans:

Table 15

Percentage of Companies Offering Retirement Plans

| Plan Type | Percent Offering |

| All Retirement Plans | 46% |

| Defined Benefit Plans | 10% |

| Defined Contribution Plans | 44% |

The fact that mostly large companies continue to offer defined benefit plans is borne out by a recent survey by Watson Wyatt. The overall rate of DB sponsorship among Fortune 1000 companies in 2009 is 61%. Interestingly enough, 19% of the Fortune 1000 companies (31% of the companies that sponsor DB plans) have frozen their plans to new participants.

A very small percentage of workers, 3%, covered by defined benefit plans are required to contribute to the plan as a condition of participation.

Recent Trends

Wisconsin Retirement System. A number of changes have been made over the years to the Wisconsin Retirement System, as outlined below. The system has been relatively stable over the last 15 years. When changes do occur, such changes generally have enhanced benefits.

In the 1995 legislative session, Wisconsin Act 302 made a number of changes to the WRS to conform to the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code in order to ensure that the WRS continues to operate as a tax-qualified governmental retirement plan. Among the changes:

- An annual ceiling was established governing the maximum amount of contributions that may be made to a participant’s account;

- An annual ceiling was established on the maximum amount of annual benefits that may be paid to an annuitant;

- A required beginning date for annuity benefit payments was established, based on the age of the participant;

- Procedures were established for determining annuity options and the value of annuities payable to former spouses under a divorce decree;

- Revised procedures were set in place for the distribution of abandoned retirement accounts; and

- A 30-day break-in-service standard was established governing the minimum time period that must elapse before a new WRS retiree could reenter WRS-covered service as an active employee without having his or her annuity terminated.

The 1999 Legislature enacted WRS benefit improvements and funding changes in Wisconsin Act 11. The Act provided for significant benefit increases:

WRS formula benefit multipliers were increased for all creditable service earned prior to January 1, 2000;

The maximum initial amount of a formula-based retirement annuity was increased for certain WRS participant classifications;

- Annual interest crediting caps were repealed for certain WRS participants, effective December 30, 1999;

- The Variable Fund was reopened to all WRS participants, first effective January 1, 2001; and

- Death benefits payable to WRS participants who die before reaching minimum retirement age were increased, effective December 30, 1999.

Among the changes in Act 11 was a change to adjust the actuarial assumptions governing the annual funding needs of the WRS. The constitutionality of Act 11’s provisions was challenged. On June 12, 2001, the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the Act 11 benefit improvements and funding changes.

In the 2003 legislative session, Wisconsin Act 22 included provisions that authorized WRS participants to transfer funds from certain tax-sheltered annuity plans to ETF for the purpose of buying forfeited service, other governmental service, and a variety of other types of service.

Private Sector Retirement Plans. In a survey recently conducted by Mercer of the S&P 500 companies, it was found that 376 of the companies sponsor a defined benefit plan, 108 companies sponsor only a defined contribution plan and 360 sponsor both a defined benefit plan and a defined contribution plan.

For the first time in 2008, median spending on defined contribution benefits (which has remained relatively constant as a percentage of revenue) exceeded the median spending on defined benefit accruals. This is likely due to a significant number of defined benefit plans that have frozen their benefit accruals, either voluntarily or involuntarily (due to the forced requirements of the Pension Protection Act for plans that are severely underfunded).

This shift points to the fact that employees are bearing a larger share of both:

- The costs of retirement benefits; and

- The risk of retirement investments.

The decline in the number of defined benefit plans can be seen dramatically in excerpts from this table published by the Department of Labor:

Table 16

Number of Single Employer Plans for Years 1975-2006*

Year | Total | Defined Benefit | Defined Contribution |

| 1975 | 308,651 | 101,214 | 207,437 |

| 1980 | 486,142 | 145,764 | 340,378 |

| 1985 | 629,069 | 167,911 | 461,158 |

| 1990 | 709,404 | 111,251 | 598,153 |

| 1995 | 690,265 | 67,682 | 622,584 |

| 2000 | 732,654 | 47,015 | 685,639 |

| 2005 | 676,151 | 46.090 | 630,061 |

| 2006 | 691,513 | 47,042 | 644,440 |

*Includes plans of controlled groups of corporations and multiple-employer plans.

A survey was conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, The National Compensation Survey of Employee Benefits I the United States, March 2008.

Among the highlights of the survey:

- 51% of all private sector employees participated in a retirement plan in March 2008.

- 43% of private sector workers participated in a defined contribution plan.

- 20% of private sector workers participated in a defined benefit plan.

- The rate of participation varied by occupational group.The only surveyed group that had greater participation in defined benefit plans than defined contribution plans was unionized workers as shown in Table 18:

Table 17

Percent of Private-Industry Workers Who Participate in Retirement Plans

Occupational Group | Defined Benefit Plan | Defined Contribution Plan | Either plan or both plans |

| Management, business, and financial | 34 | 69 | 77 |

| Professional and related | 26 | 56 | 64 |

| Service | 8 | 20 | 25 |

| Sales and related | 13 | 41 | 46 |

| Office and administrative support | 22 | 52 | 60 |

| Construction, extraction, farming, fishing, and forestry | 24 | 35 | 47 |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 26 | 48 | 58 |

| Production | 27 | 45 | 57 |

| Transportation and material moving | 24 | 38 | 51 |

The only surveyed group that had greater participation in defined benefit plans than defined contribution plans was unionized workers:

Table 18

Percent of Private-Industry Workers Who Participate in Retirement Plans

Bargaining Unit Status | Defined Benefit Plan | Defined Contribution Plan | Either Plan or Both Plans |

| Union | 67 | 42 | 80 |

| Non-Union | 15 | 43 | 48 |

Global Comparison Between Wisconsin’s Public and Private Pension Plans

Employer Contributions under the WRS. Employer-required contributions are not fixed by statute. Such contributions are determined each year, based on the actuarially determined total revenue requirements of the WRS, once employee-required contributions and investment earnings have been accounted for.

The following table shows the breakdown of employee, benefit adjustment, and employer contributions for calendar years 1998 – 2007:

Table 19

Contributions to WRS Plan for Calendar Years 1998 – 2007 (In thousands $)

| Calendar Year | Employee-Required Contributions | Benefit Adjustment Contributions * | Employer Contributions | Totals |

| 1998 | 432,221 | 92,601 | 562,063 | 1,086,885 |

| 1999 | 444,639 | 63,818 | 657,808 | 1,166,265 |

| 2000 | 460,586 | 42,264 | 556,721 | 1,059,571 |

| 2001 | 478,326 | 17,686 | 627,046 | 1,123,058 |

| 2002 | 494,772 | 18,266 | 914,575 | 1,427,613 |

| 2003 | 513,786 | 37,713 | 1,728,161 | 2,279,660 |

| 2004 | 529,654 | 57,726 | 637,926 | 1,225,306 |

| 2005 | 544,747 | 78,503 | 599,204 | 1,222,454 |

| 2006 | 563,008 | 90,842 | 583,201 | 1,237,051 |

| 2007 | 583,785 | 104,259 | 614,010 | 1,302,054 |

| Totals | 5,045,524 | 603,678 | 7,480,715 | 13,129,917 |

* Benefit Adjustment Contributions are required by statute and may be paid by the employer or the employee, depending upon the employer’s compensation plan.

Employee Contributions under the WRS. As discussed earlier, the statute requires employee contributions as follows:

Table 20

Employee-Required Contributions by Group

Group | Rate |

| General | 5.0% |

| Executives and Elected Officials | 5.5% |

| Protective Employees With Social Security | 6.0% |

| Protective Employees without Social Security | 8.0% |

Although the employee contribution rates are set by statute, nearly all employers pick up the employee-required contributions. The statute specifically authorizes an employer to pay on behalf of an employee all or part of any employee-required contributions.

According to a paper issued by the Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau in January 2009, “Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System,” between 99.4% and 99.8% of employee-required contributions were picked up by the employer in calendar years 1998 through 2007.

Contributions as a Percentage of Payroll. The following table is taken from the actuarial valuation prepared by Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company for the Wisconsin Retirement System as of December 31, 2008. It reflects the contribution rates for 2009 and 2010, expressed as a percentage of participants’ payroll. This allows a comparison between WRS and private sector plans.

If the rates in Table 21 are adjusted for the average employer pick-up rate of 99.5%, then the breakdown of employer and employee contributions as a percentage of payroll is shown in Table 22.

Table 21

Comparative Summary of Valuation Results Contribution Rates for Indicated Year Expressed as a Percentage of Participant Payroll (click to enlarge:)

Table 22

Adjusted Employer Contributions after Taking Employer Pick-Up into Account

| Category | Employer Contribution as a Percentage of Payroll | Employee Contribution as a Percentage of Payroll | ||

| 2009 | 2010 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| General Participants | 10.55% | 11.14% | .05% | .06% |

| Executives & Elected Officials | 11.84% | 11.44% | .06% | .06% |

| Protective Occupation with Social Security | 13.13% | 14.03% | .07% | .07% |

| Protective Occupation Without Social Security | 14.03% | 15.42% | .07% | .08% |

Contributions under Private Sector Defined Contribution Plans

The Profit Sharing/401k Council of America released its 50th Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans. This survey reported the 2006 plan year experience of 1,000 plans with more than six million participants. Company contributions to defined contribution arrangements averaged 4.7% of payroll in 2006. Such contributions were highest in profit sharing plans (9.2% of payroll) and lowest in 401(k) plans (3.0% of payroll).

Benefits Provided under the WRS Plan

Table 23 provides information regarding the benefits provided to individuals covered by WRS. The table, taken from Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January 2009, illustrates the benefits provided for individuals at various rates of pay and years of service. For purposes of the formula benefit, it is assumed that the individual has eight years of creditable service earned after 1999, and the remainder earned before 2000.

Table 23

Illustrations of Normal Retirement Age 65 Monthly Annuity Amounts

Monthly Final Average Earnings (FAE) | WRS Annuity | Social Security | Monthly Total | Amount% of FAE |

| 35 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $1,209 | $955 | $2,164 | 108% |

| $3,000 | $1,814 | $1,245 | $3,059 | 102% |

| $4,000 | $2,418 | $1,536 | $3,954 | 99% |

| $5,000 | $3,023 | $1,716 | $4,739 | 95% |

| 25 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $856 | $955 | $1,811 | 91% |

| $3,000 | $1,284 | $1,245 | $2,529 | 84% |

| $4,000 | $1,712 | $1,536 | $3,248 | 81% |

| $5,000 | $2,140 | $1,716 | $3,856 | 77% |

| 15 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $503 | $955 | $1,458 | 73% |

| $3,000 | $755 | $1,245 | $2,000 | 67% |

| $4,000 | $1,006 | $1,536 | $2,542 | 64% |

| $5,000 | $1,258 | $1,716 | $2,974 | 59% |

Benefits Provided under Private Sector Defined Contribution Plans

A study prepared by the Employee Benefit Research Institute looked at the average 401(k) account balance at the end of 2007. For participants in their 60s, the median account balance varied based on the salary of the individual:

Table 24

Median 401(k) Account Balance by Salary Range

Salary Range | Median Account Balance |

| $20,000-$40,000 | $58,028 |

| $40,000-$60,000 | $97,413 |

| $60,000-$80,000 | $162,683 |

| $80,000-$100,000 | $236,612 |

| >$100,000 | $344,849 |

If such individuals were to retire at age 65 and annuitize their benefits, the estimated benefits payable from the 401(k) account balances are shown below:

Table 25

Estimated Replacement Ratios from Private Sector 401(k) Plans

Salary Range | Median Account Balance | Estimated Annual Annuity | Percent Replacement |

| $20,000- $40,000 | $58,028 | $5,571 | 18.57% |

| $40,000- $60,000 | $97,413 | $9,352 | 18.70% |

| $60,000- $80,000 | $162,683 | $15,618 | 22.31% |

| $80,000- $100,000 | $236,612 | $22,715 | 25.24% |

| >$100,000 | $344,849 | $33,106 | 27.59% |

The replacement ratios in Table 25 can be compared with the replacement ratios for the WRS plan, which can range between 25% and 80% of pay, depending upon years of service. The above estimates of annual annuity benefits are merely theoretical for a number of reasons:

- Very few 401(k) plan participants will purchase an annuity with their 401(k) funds; they are more likely to roll the funds into an IRA;

- Even if participants do purchase annuities, the rates are not likely to be as favorable to them (retail vs. wholesale rates);

- 401(k) participants, after years of exercising control over their investments, will generally be reluctant to give up control of their investments after retirement;

- The account balances are based on values as of December 31, 2007, and many 401(k) plan participants suffered a significant drop in value between January 1, 2008 and the present time.

Options for Changing Public Pensions

Limitations in Making Changes to Public Pensions. State constitutions and local charters, as well as state law and local ordinances, may include explicit protections for pension benefits, such as guarantees that pensions earned by state and local government employees cannot be eliminated or diminished.

Generally speaking, future pension benefits may be changed, both for new hires and for the future service of current employees, as long as accrued benefits (i.e. benefits attributable to past service) are not reduced.

Changes in Other Public Pension Systems

Alaska

In 2005, Alaska Gov. Frank Murkowski signed legislation switching the state’s defined benefit pension retirement system to 401(k)-type defined-contribution accounts for teachers and state employees hired after July 1, 2006. The DC individual account system would be the only retirement plan for public workers (hired after July 1, 2006), as Alaska’s state and local employees do not participate in Social Security.

Colorado

In 2006, the Colorado Public Employee Retirement Association (PERA) found itself facing proposals to convert its DB pension system to a DC system. Today, PERA is a substitute for Social Security for most public employees, and provides retirement and other benefits to nearly 280,000 active and retired employees of more than 400 government agencies and public entities. Ultimately, the compromise measure that was adopted maintained the DB system for all employees while restoring the funding level, which had previously dropped to about 74%. Interestingly, the accelerated funding of the PERA plan was to come from employees, not employers. Under the compromise, employees of the community college system could choose either a DC or a DB plan. The minimum retirement age for new employees was raised from age 50 to 55.

Florida

The Florida Retirement System (FRS) Investment Plan was established by the Legislature to provide Florida’s public employees with a portable, flexible alternative to the FRS traditional defined benefit plan. Since opening its first employee account in July 2002, the FRS Investment Plan has become one of the largest optional public-sector defined contribution retirement plans in the U.S., with over 118,000 members and $3.7 billion in assets as of December 31, 2008.

Michigan

In 2007, the Senate made changes to the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System (MPSERS). The change was not a switch from a DB system to a DC system, but made some significant changes nonetheless:

- New employees would have to make larger contributions: 6.4% of pay in excess of $15,000 (currently: 4.3% of pay in excess of $15,000);

- Pay 10% of retirement health care costs;

- Receive prorated benefits if they have less than 30 years of service at retirement (currently available for employees with 10 years of service)

The cost savings of these changes will not emerge for at least 10 years, when retirees covered by the revised rules begin to draw benefits.

Nebraska

The state of Nebraska is a high-profile example of a public sector employer that offered a defined contribution plan as the primary retirement plan to a large number of public employees, while it offered a defined benefit plan to other state employees. Nebraska found that the defined contribution plan was not adequate to ensure that all workers would have sufficient retirement income. In 2003, it established a new cash balance defined benefit plan for employees who otherwise would have had to rely on the defined contribution plan. The conclusion reached by the House Committee on Pension and Investments in 2000 was:

“We have had over 35 years to ‘test’ this experiment and find generally that our defined contribution members retire with lower benefits than their defined benefit counterparts.”

West Virginia

West Virginia moved from a traditional pension plan to private accounts- and then recently returned to a traditional plan.

Specific Changes to Be Considered in Wisconsin

1. Reinstate Employee Contributions

As discussed previously, although the statute sets the employee-required contribution level, the practical impact is that the employers currently pick up over 99.5% of the employee’s cost. By requiring employees to actually pay the statutorily set rates, the employer contributions could be reduced considerably.

Based on the 2008 contributions as found in the December 31, 2008 Annual Actuarial Valuation prepared by Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company, the total participant contributions were approximately $619,286,000. The chart below shows the employer cost savings if the employees were to pay the approximate percentage of their employee-required contributions:

Table 26

Estimated Annual Cost Savings If Employees Pay a Portion of Statutorily Set Rates

Employee Percentage Paid by Employees | Estimated Annual Cost Savings |

| 20% | $123,857,000 |

| 40% | $247,714,000 |

| 60% | $371,572,000 |

| 80% | $495,429,000 |

| 100% | $619,286,000 |

As an alternative, the employee percentage paid could be phased in over a number of years to lessen the impact on employee take-home pay. For example, the 2012 teacher rate could be set at 1% of pay, gradually increasing to 5% of pay in 2016.

2. Initiate Defined Contribution Plan as an Option or a Requirement for New Hires

A number of states have tried the approach of closing the defined benefit plan to new hires and offering a DC option to such new hires. Short term, this will likely not result in cost savings for the employers, given that the large bulk of the plan’s cost is attributable to longer-service employees. Ultimately, this may result in cost savings, depending upon the level of contributions in the DC plan.

Alternatively, some states have considered the option of offering existing participants the choice of the DB plan or an alternative DC plan. As discussed above, this may not result in any short-term savings for the employers, as long-service employees will likely choose to stay with the defined benefit plan.

3. Fix the Employer Contribution and Require the Employee’s Share to Be Adjusted

Under the statute governing the WRS, the employee-required contribution rates are fixed, as shown in Table 27.

Table 27

Employee-Required Contribution Rates

Group | Rate |

| General | 5.0% |

| Executives and Elected Officials | 5.5% |

| Protective Employees with Social Security | 6.0% |

| Protective Employees Without Social Security | 8.0% |

In addition, benefit adjustment contributions may also be required by statute. The employers and employees share the investment risk. Because, from a practical standpoint, the employers pick up 99.5% of the employee-required contributions, the employers are really bearing the investment risk. By requiring the employee’s share to be adjusted and fixing the employer contributions, the actual employer contributions would be substantially reduced. The theoretical contributions (had this been in place over the last few years) are shown in Table 28.

Table 28

WRS Contributions for Calendar Years 1998 – 2007

| Calendar Year | Employee Fixed Contribution | Benefit Adjustment Contributions | Employer Contributions | Totals |

| 1998 | 432,221 | 92,601 | 562,063 | 1,086,885 |

| 1999 | 444,639 | 63,818 | 657,808 | 1,166,265 |

| 2000 | 460,586 | 42,264 | 556,721 | 1,059,571 |

| 2001 | 478,326 | 17,686 | 627,046 | 1,123,058 |

| 2002 | 494,772 | 18,266 | 914,575 | 1,427,613 |

| 2003 | 513,786 | 37,713 | 1,728,161 | 2,279,660 |

| 2004 | 529,654 | 57,726 | 637,926 | 1,225,306 |

| 2005 | 544,747 | 78,503 | 599,204 | 1,222,454 |

| 2006 | 563,008 | 90,842 | 583,201 | 1,237,051 |

| 2007 | 583,785 | 104,259 | 614,010 | 1,302,054 |

| Totals | 5,045,524 | 603,678 | 7,480,715 | 13,129,917 |

Other Changes

Before beginning a discussion of changes to the WRS, it is important to consider the adequacy of retirement benefits. Adequacy is commonly measured by using replacement ratios.

Replacement Ratios. Replacement ratios are commonly used to measure the adequacy of retirement benefits. A replacement ratio computed for employees at different levels of compensation can be used to measure the adequacy of current benefits and to compare the benefit package with those of other employers.

A replacement ratio is obtained by dividing total projected retirement income (including Social Security) by current pay at the time of retirement. For example, assume that someone earns $60,000 per year before retirement. If this individual receives $45,000 in Social Security and other retirement income, this individual’s replacement ratio is 75% ($45,000 / $60,000).

Generally, an individual needs less gross income after retiring, primarily due to four factors:

- Income taxes are generally reduced because of extra tax deductions allowed for those over age 65;

- Social Security taxes (FICA deductions from wages) generally end completely at retirement;

- Social Security benefits are partially or fully tax-free;

- Saving for retirement is no longer needed.

Table 29 shows that a 78% replacement ratio would allow an employee earning $60,000 to retire at age 65 in 2008 without reducing his or her standard of living. Because taxes and savings decrease at retirement, this individual is just as well off after retirement with a gross income of only $46,972.

Table 29

Replacement Ratio for Employee Earning $60,000 Who Retires at Age 65

| Annual Income Before Retirement | Annual Income After Retirement | Replacement Ratio | |

| Gross Income | $60,000 | $46,972 | 78% |

| (Taxes) | (10,967) | (49) | |

| (Savings) | (2,225) | 0 | |

| Age and Work Related Expenditures | (35,253) | (34,358) | |

| Amount Left for Other Living Expenses | $12,555 | $12,555 |

Typical adequacy standards vary by income level and decline as income increases. A recent study by Aon Consulting and Georgia State University provided the desired income replacement ratios at retirement. This is assuming a family situation in which there is one wage earner who retires at age 65 with a spouse age 62. Thus, the family unit is eligible for family Social Security benefits, which are 1.375 times the wage earners benefit.

Table 30

2008 Replacement Ratio Findings

Pre-Retirement Income | Social Security | Private and Employer Sources | Total |

| $20,000 | 69% | 25% | 94 |

| $30,000 | 59% | 31% | 90 |

| $40,000 | 54% | 31% | 85 |

| $50,000 | 51% | 30% | 81 |

| $60,000 | 46% | 32% | 78 |

| $70,000 | 42% | 35% | 77 |

| $80,000 | 39% | 38% | 77 |

| $90,000 | 36% | 42% | 78 |

Source: The 2008 Replacement Ratio Study, conducted by Aon Consulting and Georgia State University

There are three significant points about the replacement ratio calculations:

1. Social Security replaces a larger portion of pre-retirement income at lower wage levels.

2. Total replacement ratios that are required to maintain an individual’s pre-retirement standard of living are highest for the very lowest-paid employees, primarily for two reasons:

a. Before retirement, lower-paid employees save the least and pay the least in taxes as a percentage of their income; and

b. Age-and work-related expenditures do not decrease by as much, as a percentage of income, for the lower-paid employees.

3. After reaching an income level of $60,000, the total required replacement ratios remain fairly

constant at 77% – 78% of pre-retirement income. This is due to the fact that post-retirement taxes

increase for higher-paid employees. For the highest-income married couple, as much as 85% of

the Social Security benefit could be taxable.

Replacement Ratios and the WRS Plan. Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009, Chapter 5, WRS Benefits, provides a statement consistent with the above discussion of replacement ratios:

“…For the WRS, the general expectation is that upon retirement a career employee will no longer incur Social Security tax payments or work-related expenses and will usually move into a lower post-retirement income tax bracket. The goal is that these expenditure reductions coupled with the start of Social Security benefits, a WRS retirement annuity and personal savings should typically provide the individual with spendable income approximately equal to his or her pre-retirement disposable earnings.”

The existing defined benefit formula provides a relatively generous benefit for a long-service employee. For example, a 30-year employee can expect to receive a benefit between 48% of FAE and 53% of FAE, beginning as early as age 57.

This is further illustrated in Table 31, taken from the Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009. The following table illustrates and reinforces the relatively generous benefits provided for individuals at various rates of pay and years of service. For purposes of the formula benefit, it is assumed that the individual has eight years of creditable service earned before January 1, 2000, and the remainder earned after 2000. As can be seen by the following table, benefits equal to or more generous than the recommended replacement ratios are provided for employees with 25 or more years of service.

Table 23

Illustrations of Normal Retirement Age 65 Monthly Annuity Amounts

Monthly Final Average Earnings (FAE) | WRS Annuity | Social Security | Monthly Total | Amount% of FAE |

| 35 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $1,209 | $955 | $2,164 | 108% |

| $3,000 | $1,814 | $1,245 | $3,059 | 102% |

| $4,000 | $2,418 | $1,536 | $3,954 | 99% |

| $5,000 | $3,023 | $1,716 | $4,739 | 95% |

| 25 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $856 | $955 | $1,811 | 91% |

| $3,000 | $1,284 | $1,245 | $2,529 | 84% |

| $4,000 | $1,712 | $1,536 | $3,248 | 81% |

| $5,000 | $2,140 | $1,716 | $3,856 | 77% |

| 15 Years of Service | ||||

| $2,000 | $503 | $955 | $1,458 | 73% |

| $3,000 | $755 | $1,245 | $2,000 | 67% |

| $4,000 | $1,006 | $1,536 | $2,542 | 64% |

| $5,000 | $1,258 | $1,716 | $2,974 | 59% |

Redesigning the WRS Plan. A number of options exist to make smaller, incremental changes to the WRS to reduce employer costs:

- Change the definition of final average earnings (FAE): The current formula benefit is based on the three highest years of earnings. This could be modified to use the three consecutive or five consecutive highest-paid years. Alternatively, the last 10 years before normal retirement could be the basis of determining the three- or five-year average.

- Use a career average formula: The same multiplier could be used; e.g. 1.6% for teachers. In essence, the formula benefit would be not be weighted for the highest three years of pay.

- Eliminate the variable portion: The variable portion of the money purchase benefit is very helpful to employees in bull market times. However, in bear markets, this can result in a significant reduction in benefits. By eliminating the variable portion of the benefit, two favorable results will happen:

a. Employees will have the security of knowing that their future benefits will not be reduced

b. Employers will know that favorable investment returns will reduce their costs and,

potentially, the employee’s cost - Reduce the multiplier: As discussed above, the existing multiplier results in a benefit of between 48% and 53% of FAE for teachers. Looking at the replacement ratio tables, a reasonable objective might be 40% of FAE. A reduction in the multiplier to 1.33% of FAE would still meet the threshold for benefit adequacy for a 30-year employee or a reduction to 1.6% of FAE for a 25-year employee.

- Eliminate the money purchase benefit: The money purchase benefit generally provides greater benefits to the long-service employee. As demonstrated above, the current formula benefit exceeds the adequacy level recommended. By eliminating the money purchase benefit, employer contributions will be reduced. The participant contributions could be directed towards a 401(k)-style account or a 403(b) plan.

- Increase the retirement age: Based on increased longevity, it is inevitable that the Social Security Retirement age will be increased. It may make sense to gradually increase the age at which unreduced benefits will be paid. Currently, a 30-year employee may receive unreduced benefits as early as age 57. This could also have the impact of keeping long-service, high-performing employees working longer.

- Eliminate or scale back post-retirement increases: Annuities are currently increased annually if all these conditions are satisfied:

a. The investment income credited to retired life

funds is in excess of the assumed rate (currently 5%),

b. Other plan experiences are within projected ranges,

c. The resulting adjustment would be at least ½%. - The net result of these existing provisions is that retired participants in WRS will gain in bull markets, but stay even in bear markets. Perhaps an increase tied to the cost of living would improve the benefit security of participants, while allowing employers to reduce contributions when returns are favorable. It is clear currently that employers and non-retired participants will have to increase their contributions when returns are unfavorable.

- Integrate the benefits with Social Security: Given that most classifications of employees under the WRS are covered by Social Security, it may make sense to provide a benefit formula that takes Social Security into account. Some examples of potential formulas are shown below:

a. [2% multiplied by FAE minus 1% multiplied by PIA] multiplied by credited service.

b. [1.5% multiplied by FAE + .5% multiplied by (FAE-covered compensation] multiplied by credited service.

Note: PIA is the Primary Insurance Amount, generally the Social Security benefit payable at Social Security retirement age. Covered compensation is the average of the Maximum Taxable Wage Base for all years in the Social Security system.

Appendix A

Benefit Provisions in the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS)

This appendix provides more detail regarding the provisions in the WRS plan.

Normal Retirement Age. The normal retirement age is the age at which the participant becomes eligible for an unreduced age and service benefit and depends on the employment category, age, and years of service:

Table 32

Normal Retirement Age Under the WRS Plan

| General | General | Protective | Protective | Executive and Elected | Executive and Elected | |

| Age | Service | Age | Service | Age | Service | |

| Earlier of: | 65 | Any* | 54 | Any* | 62 | Any* |

| 57 | 30 | 52 | 25 | 57 | 30 |

For example, assume that an employee in the general category starts working at age 30. The employee (assuming continuous work) will have 30 years of service at age 60, and can retire with an unreduced benefit beginning at age 60. Contrast that with an employee in the general category who starts working at age 45. Unreduced benefits will not be available to this employee until age 65.

Table 33

Service Multipliers in the WRS Plan

| Multiplier for Service Performed After 1999 | Multiplier for Service Performed Before 2000 | Group |

| 2.0% | 2.165% | Executive group, elected officials and protective occupation participants covered by Social Security |

| 2.5% | 2.665% | Protective occupation participants not covered by Social Security |

| 1.6% | 1.765% | All other participants |

Normal Retirement Benefit. The normal retirement benefit is the greater of two items:

1. The Formula Benefit

2. The Money Purchase Benefit

The Formula Benefit. The normal retirement benefit payable at normal retirement age is based on final average earnings (FAE) and creditable service (CS) and depends on the employment category as shown in Table 33.

FAE is generally the average of the three highest years of earnings preceding retirement. The years do not have to be consecutive.

As an example, a teacher retires at age 62 with 30 years of service, 10 years performed after 1999 and 20 years before 2000. The teacher’s FAE is $48,000, and the monthly retirement benefit is computed as follows:

[ (1.6% X $48,000 X 10) + (1.765% X $48,000 X 20) ] /12 = $2,052

The maximum formula benefit is shown in the table below:

Table 34

Maximum Formula Benefit by Group

Maximum Formula Benefit | Group |

85% of FAE | Protective occupation participants not covered by Social Security |

65% of FAE | Protective occupation participants covered by Social Security |

| 70% of FAE | All other participants |

The Money Purchase Benefit. A money purchase retirement benefit is calculated by multiplying the employee and employer deposits in the employee’s account by an actuarial money purchase factor based on the age when the annuity begins. The interest rate credited to the account will depend on whether the employee elects a fixed or variable fund. For example, in 2004, the fixed rate was 8.5% and the variable rate was 12%. Recently, the variable rate has been negative. The table below shows sample rates for converting the accumulated employer and employee accounts to a monthly benefit.

Table 35

Money Purchase Factors to Convert Money Purchase Accounts to Annuities

Age | Monthly Benefit Factor |

| 50 | .00530 |

| 55 | .00570 |

| 60 | .00625 |

| 65 | .00705 |

| 70 | .00822 |

For example, assume that the sum of the employee and employer accounts for an employee at age 60 is $300,000. The money purchase benefit for the employee is:

$300,000 X .00625 = $1,875

Such an employee would receive the greater of the formula benefit described above, or the money purchase benefit of $1,875 per month at age 60.

Payment of Benefits. The normal form of benefit is a straight life annuity with no death benefits. Optional forms of benefit (actuarially reduced) are shown below:

- A life annuity with 60 or 180 monthly payments guaranteed;

- A joint and 75% survivor annuity;

- A joint and 100% survivor annuity;

- A joint survivorship annuity reduced 25% upon either the employee’s death or the beneficiary’s death;

- A joint and 100% survivor annuity with 180 monthly payments guaranteed.

Early Retirement. Any employee who has attained age 55 and any protective occupation employee who has attained age 50 may apply for an early retirement benefit. The benefit is reduced .4% for each month that the annuity effective date precedes the normal retirement age. For non-protective employees terminating employment after June 30, 1990, the .4% reduction factor is reduced for months after the attainment of age 57 and before the annuity effective date by .001111% for each month of creditable service.

For example, an employee has 20 years of creditable service and retires at age 60 (five years or 60 months before the normal retirement age of 65). The reduction of .4% per month is reduced by .02222% (20 X .001111%). Assume that the monthly retirement benefit at age 65 is $1,000 per month. The reduced benefit payable at age 60 is:

$1,000 X (.4% – .02222%) X 60 months = $773.33

Thus, the benefit payable at age 60 is $773.33 per month.

Termination of Employment before Benefit Eligibility. An employee has two choices if he or she leaves before becoming eligible for early or normal retirement benefits under the WRS plan:

- Receive a refund of accumulated employee contributions; or

- Leave contributions on deposit and apply for a retirement benefit after the minimum retirement age based on accrued service at the time of termination of employment.

Disability Benefits. In order to be eligible for disability benefits, an employee must have a total and permanent incapacity to engage in gainful employment. The employee must have completed at least six months of creditable service in each of at least five out of the last seven calendar years preceding application for disability. The service requirement is waived if the disability results from service-related causes.

For protective occupations, eligibility also can be met if a member:

- Has 15 years of service;

- Is between ages 50 and 55; and

- Is unable to safely and efficiently perform his/her duties.

The benefit is payable generally to participants who elect long-term disability income coverage. The benefit payable until age 65 is 40% of FAE for participants covered by Social Security and 50% of FAE for non-covered participants who cannot qualify for Social Security disability benefits.

After age 65, the normal retirement benefit is payable and is generally based on the benefit accrued as of the date of disability.

Death Benefits. If a participant dies while in service, the death benefit is calculated as shown in the table below:

Table 36

Death Benefit under the WRS Plan for Various Categories of Employees

For Protective Employees | For Other Employees | Amount of Death Benefit |

| Prior to Age 50 | Prior to Age 55 | Equivalent of twice the accumulated employee contributions required and all additional contributions and employer amounts contributed prior to 1974 for teachers, or 1966 for others |

| After Age 50 | After Age 55 | The amount that would have been paid if the participant had retired and elected the 100% survivor option |

Post-Retirement Adjustments. Annuities are increased annually post-retirement if all these conditions are satisfied:

- The investment income credited to retired life funds is in excess of the assumed rate (currently 5%),

- Other plan experience is within projected ranges, and

- The resulting adjustment is at least 0.5%.

Contribution Rates. The financial objective of the Wisconsin Retirement System is to “establish and receive contributions that will remain level from year to year and decade to decade.” The statute requires participant contributions as follows:

Table 37

Required Participant Contributions

Group | Rate |

| General | 5.0% |

| Executives and Elected Officials | 5.5% |

| Protective Employees with Social Security | 6.0% |

| Protective Employees without Social Security | 8.0% |

Employee Contributions. Although the employee contribution rates are set by statute, nearly all employers pick up the employee-required contributions. The statute specifically allows an employer to pay on behalf of an employee all or part of any employee-required contributions.

Benefit Adjustment Contribution. Under the 1983 Wisconsin Act 141, significant increases in WRS retirement benefits were authorized by the Legislature. In order to help fund these benefit improvements, a new statutory contribution known as the “benefit adjustment contribution” was established. Initially, the benefit adjustment contribution rate was set at 1% of gross earnings and applied only to WRS participants in the general employee classifications and the protective service with Social Security classification (i.e., protective employees other than local firefighters). Benefit adjustment contributions were first imposed on gross earnings in 1986.

Under the statute, the benefit adjustment contribution is to be paid by the employee. Like other employee-required contributions, however, an employer may elect to pay the benefit adjustment contribution on behalf of the employee. All of the benefit adjustment payments are credited to the employer accumulation account.

Non-refundable benefit adjustment contributions are also required by statute and may be paid by the employer or by the employee, depending upon the employer’s compensation plan. The employers contribute the remaining amounts necessary to fund the retirement system on an actuarially sound basis. As differences between actual and assumed experience emerge, adjustments are made to contributions to maintain financial balance as follows:

1. One-half of the increase or decrease is reflected in the employer normal cost rate

2. One-half of the increase or decrease is reflected in the participant-paid portion of the benefit adjustment contribution. If a decrease would reduce a benefit adjustment contribution to less than zero, participant normal contributions are reduced.

Notes

Background

Stephen A. Sass, The Promise of Private Pension: The First Hundred Years (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997)

http://www.menke.com/information/history.php

http://www.nceo.org/main/column.php/id/211

Beth Almeida and William Fornia, Defined Benefit Plans: A Better Bang for the Buck, Journal of Pension Benefits, Vol. 16, Number 2, Winter 2009

http://www.watsonwyatt.com/news/press.asp?ID=21854, Watson Wyatt press release, July 22, 2009

http://etf.wi.gov/members/benefits_retirement.htm

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/wrs_active_lives_2008.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4930.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4107.pdf

Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January 2009

National Reference

Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009

1999/2000 Retirement Plans Survey, MRA, May, 2000 (MRA provided this information to WPRI and stipulated that the names of the individual companies participating in the survey cannot be disclosed.)

2009/2010 HR Policies & Benefits Survey, Volume 2: Wisconsin/Northern Illinois, Western Illinois & Iowa, MRA, March, 2009 (MRA provided this information to WPRI and stipulated that the names of the individual companies participating in the survey cannot be disclosed.)

2007/2008 Wisconsin & Northern Illinois Policies & Benefits Survey, Volume 2, MRA, 2007 (MRA provided this information to WPRI and stipulated that the names of the individual companies participating in the survey cannot be disclosed.)

2005/2006 Wisconsin & Northern Illinois Policies & Benefits Survey, MRA, March, 2005 (MRA provided this information to WPRI and stipulated that the names of the individual companies participating in the survey cannot be disclosed.)

“National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, March 2007”, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, August 2007

“National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, March 2008”, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2009

http://www.watsonwyatt.com/news/press.asp?ID=21854, Watson Wyatt press release, July 22, 2009

“50th Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans”, Profit Sharing/401k Council of America

“Wisconsin Retirement System, Three-Year Experience Study, January 1, 2003 – December 31, 2005”, Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company

Recent Trends

Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009

“Program Perspectives on Retirement Benefits”, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Issue 3, March, 2009

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ebs2.nr0.htm

“Mercer: How Does Your Retirement Program Stack Up?”—2009

Private Pension Plan Bulletin Historical Tables and Graphs, U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration, 2009

Global Comparison between Wisconsin’s Public and Private Pension Plans

http://etf.wi.gov/members/benefits_retirement.htm

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/wrs_active_lives_2008.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4930.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4107.pdf

“401(k) Plan Asset Allocation, Account Balances, and Loan Activity in 2007”, Issue Brief, No. 324, December, 2008, Employee Benefit Research Institute

Options for Changing Public Pensions

Wisconsin Retirement System, Twenty-Eighth Annual Actuarial Valuation, December 31, 2008, Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company

http://www.aon.com/about-aon/intellectual-capital/attachments/human-capital-consulting/RRStudy070308.pdf

Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009

“The New Intersection of the Road to Retirement: Public Pensions, Economics, Perceptions, Politics, and Interest Groups”, Beth Almeida, Kelly Kenneally, and David Madland, September 2008, Pension Research Council Working Paper, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Michigan State and Local Government Retirement Systems, July 2009, Report 356, Citizens Research Council of Michigan

http://www.sbafla.com/fsb/InvestmentFunds/FRSInvestmentPlan/tabid/372/Default.aspx

Appendix A

http://etf.wi.gov/members/benefits_retirement.htm

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/wrs_active_lives_2008.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4930.pdf

http://etf.wi.gov/publications/et4107.pdf

Informational Paper 79, Wisconsin Retirement System, Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, January, 2009

President’s Notes:

As a former public employee, I was included in the Wisconsin Retirement System. I always knew Wisconsin’s pension system was generous. Now I know just how generous that pension system is. The report you are about to read details a yawning gap between that public pension system and the pensions offered by private sector employers in Wisconsin.

We commissioned Joan Gucciardi, a Milwaukee actuary, to apply her expertise to a comparison of public and private pensions in Wisconsin. Ms. Gucciardi clearly details just how different are the public and private sectors when it comes to pensions. Private pension systems have undergone significant changes, largely in response to changing economic circumstances. While the public sector has also been buffeted by economic turmoil, the Wisconsin Retirement System has been almost completely insulated from change. In fact, as Gucciardi’s analysis shows, the only changes in recent memory have made public pension benefits even richer.

The message from this report is clear. First, the next governor can go a long way toward resolving the looming state budget deficit by making one simple change in state law: eliminating the provision that allows public employers (taxpayers) to pay the employee share of the cost of their pension. Having employees pay one-half of the cost of their pensions would be fair, and it would save state and local taxpayers $600 million per year.

The second, and more important, message is that Wisconsin needs to reform its public pension system. It is a system that has simply overstayed its welcome. Not only is it expensive, it is far out of the mainstream when compared to what the vast majority of Wisconsin employers offer their employees. The next governor should make it a priority to bring radical reform to the Wisconsin pension system. The governor must make it a priority to eliminate the insularity that has defined the Wisconsin Retirement System.

One more thing: the governor and the Legislature should remove themselves from the retirement system. Their participation in the system is an inherent conflict of interest and stands to dampen their taste for pension reform.

– George Lightbourn