Over 100 places in Wisconsin have lost more than 20% of their population since 1990. This is the first of occasional profiles of persevering small towns in the Badger State.

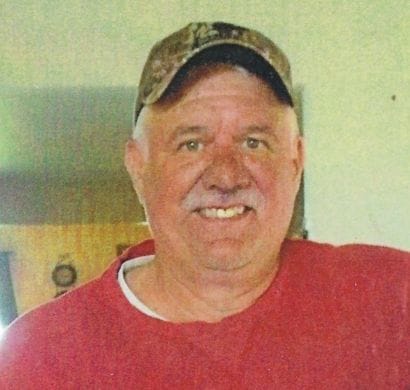

By the time he sold Codgers, one of the twin hubs of Chaseburg, Joe Berra guessed he had handed out 30 to 40 keys to the tavern.

Employees, customers, family, friends — those titles overlapped — could get in any time, day or night. In a village like this, there wasn’t a need to worry about something being stolen or a law being violated. If there were people like that here in Chaseburg, they wouldn’t be around for long, Berra said.

In many ways, Berra, 66, and the slowly dwindling number of residents define themselves by the things they have lost. Flooding of the wild and unpredictable Coon Creek in 2007 and 2018 wiped out the lower half of the village. In the upper half, three of the five bars are gone. So is the bank, the filling station and the implement store. The K-8 elementary school closed more than 15 years ago. The few children left are bused to schools miles away.

But, more important, the people of Chaseburg define themselves by their stubborn sense of community. “There’s not a better place to live,” Berra said. “There is trust in this community. Trust in each other. Like we’re all in this thing together.”

The Badger Institute, at its core, believes in the power of civil society, that space between the individual and government where our friends and families, associations and communities — perhaps, especially, small-town communities — provide the support and succor we all need to navigate life’s challenges. Many of the small towns we’re visiting have had more than their fair share.

There are 1,000 little cities, villages and towns with populations under 1,000 in the state and 420 of those with populations of less than 500, according to the most recent U.S. Census Bureau data gathered in a Badger Institute study.

Overall, Wisconsin’s rural population growth, more than 5% from 2000 through 2022, is weak compared to the urban sections of the state, but second only to North Dakota among Midwestern states, according to a Wisconsin Policy Forum study from June.

The two fastest growing counties by percentage since 2010, Dane and St. Croix, are urban, but the next five — Sawyer, Vilas, Bayfield, Burnett and Door — are rural, according to the study. Those counties have tourism in common.

In most of rural Wisconsin, population is flat or declining. The Badger Institute identified 116, or nearly 6%, of the state’s 1,939 municipal units that have lost more than 20% of their populations since 1990.

The Town of Jacobs in the southern part of Ashland County on Lake Superior at the north central tip of the state, has lost nearly 57% of its population — from 885 to 382 people — from 1990 to 2020, according to our Census Bureau review. Five others have lost between 46% and 32% percent of their populations. The Village of Yuba in Richland County had 53 people left in 2020, down 24 or 31.2% from 1990, according to our review.

Chaseburg has had the fifth steepest drop in population by percentage, just under 34%, from 365 to 241 people since 1990, according to our data.

Every square mile of Wisconsin is part of a city, village, or town and unless a municipality is annexed or two communities merge, they do not disappear, Dan Barroilhet, a research analyst with the state Demographic Services Center in Madison, said.

The tectonic shift from a farm to an industrial economy and the consolidation and organization of the lumber industry from the 19th through the 20th Centuries are the overarching reasons fewer people live in rural Wisconsin.

A demographer looks at numbers and can tell you what happened and leaves the why to other analysts and commentators, Barroilhet said. There are as many explanations for a village’s decline as there are villages, he said.

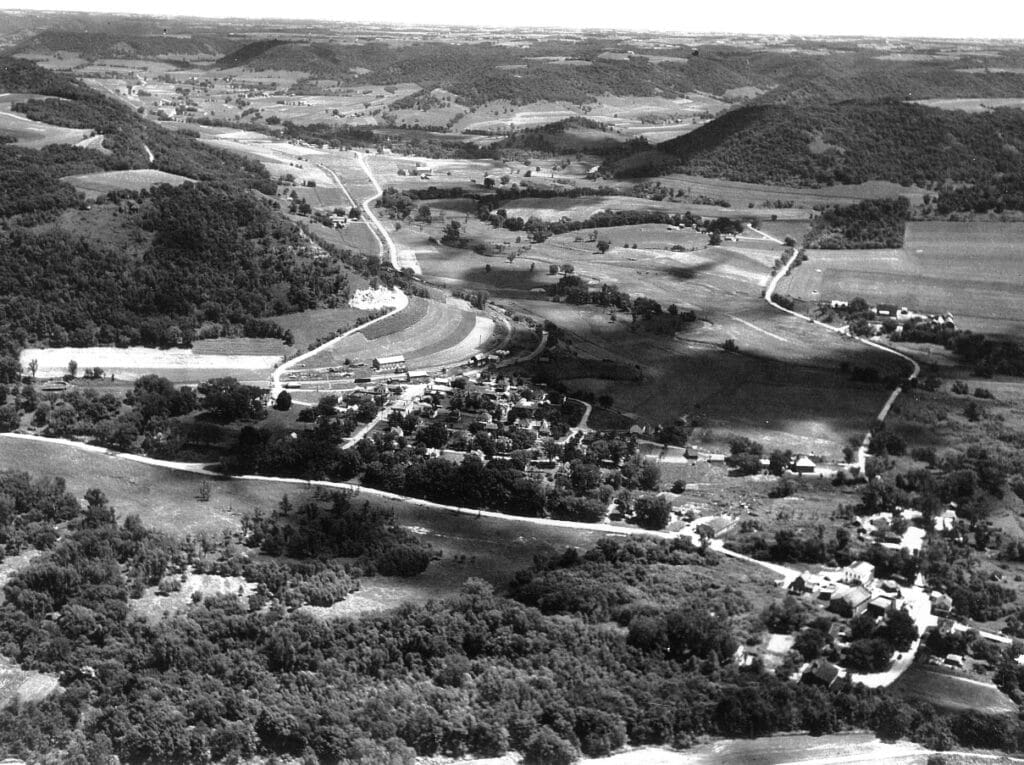

Those explanations are inextricably tied to the reasons why people built their cities, villages and towns in the first place. Chaseburg’s original homesteaders were Norwegian immigrants who found excellent farmland in the valley between the sharp bluffs on either side of Coon Creek.

Farmers built the village in the heart of what is called the Driftless Area, hundreds and hundreds of square miles that went ungraded by the receding glaciers of the Ice Age. What the settlers couldn’t know was Coon Creek was part of the largest concentrated network of freshwater creeks, streams and rivers in the world.

Coon Creek empties into the Mississippi River 7.6 miles to the west. The 125-mile Kickapoo River, the longest tributary of the Wisconsin River, the state’s longest river, cuts through the eastern quarter of Vernon County.

To look at it flowing under the small bridge on South Main Street, just west of the Old Chaseburg Cemetery, you have to wonder how this 15-foot wide, knee-deep creek could have provided the power for two sawmills, a roller mill, and a gristmill before the turn of the century.

It is hard to imagine the people of Chaseburg stubbornly rebuilding time after time after this jagged U-shaped stretch of creek, swollen by this network of freshwater streams during heavy rains, washed homes, businesses and strips of county road to other parts of the valley.

In 2007, damage from the flooding was estimated at $50 million, according to newspaper accounts at the time. In August 2018, at least 10 homes and half a dozen businesses were destroyed, putting an end to the lower half of Chaseburg.

Dagny Dahlke, 85, whose grandfather came from Norway at 20 and settled in Chaseburg in 1878, has collected copies of photos of all of the disasters in a three-ring binder she paged through one December morning at the Tippy Toe, the combination breakfast place and bar that is the other hub of the village.

At the center of the binder is a photo of the Hideaway, the boarding house, tavern, restaurant, (and onetime bordello), and a photo portrait of Ma Koenig, the no-nonsense woman who owned and ran it for 56 years.

No flood could stop Ma Koenig, at least while she was alive. She died more than 40 years before the 2018 flood forced the razing of the Hideaway. “Everyone misses the Hideaway,” Dahlke said, over coffee with her husband of 70 years, Duke Dahlke, 89. “You could spread out. It’s where families could gather, have birthday parties, meetings. In 2018, the water was as high as the bar there.”

From the window of the Tippy Toe, you can see the Chaseburg Co-Op, the agricultural feed business and the biggest building in town. Most of the dairy farms in the area sell their milk to Organic Valley, a national dairy giant based in little LaFarge, about 30 miles east of Chaseburg.

Berra isn’t optimistic that anyone is planning to build or relocate a new business on Main St. The lumber yard he once owned and sold to a bigger company a few years ago can only afford to stay open twice a week, if that, he said.

Still, the Census Bureau data shows unemployment at under .5%, a population with a median age of 38 and a percentage of population over 65 of less than 14%. The median income of $61,667 is considerably less than the state average of $71,133 but higher than most of the communities that have lost the most population by percentage, according to the data reviewed by the Badger Institute.

While the average age of the customers at Codgers is easily over 60, there are many younger families who have homes in Chaseburg, but whose breadwinners work in LaCrosse and Viroqua, the Vernon County seat. They shop, dine and send their children to school outside of Chaseburg because there is nothing for them other than the Tippy Toe or Codgers.

That isn’t to suggest they aren’t part of the community. Town Clerk Linda DeGarmo is the state’s Lead Ambassador for the American Cancer Society. From a village of 241 people, DeGarmo has raised more than $2 million since 2006, most of it through a Soleburner Walk that draws fundraising walkers from Chaseburg and every part of Vernon County.

“You will find many good things happening here,” she said.

Berra’s daughters have moved away, but still live in-state. But he and his wife, Ann, aren’t going anywhere.

“I think Chaseburg is going to stay steady,” he said. “People need to work in the city, but they want to get away from the city. People still want to live here.”

Mark Lisheron is the Managing Editor of the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited. Photos courtesy of Joe Berra.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields