A school that’s making Milwaukee’s future men navigates harsh fiscal environment

Milwaukeean Scott Stewart sounds urgent when he talks of his son Savion’s school.

“These kids need this. They need this kind of positive environment.” Otherwise, he said, “there’s no telling what these kids would be doing right now, especially in the city of Milwaukee.”

The least Wisconsin can do is listen to what Stewart and other fathers and mothers say they need.

That school, Kingdom Prep Lutheran High School, is far different than the Milwaukee Public Schools options near Stewart’s northwest side home, options he once attended. “I didn’t want my kid to get wrapped up in the wrong environment,” he said.

“I was looking out for my kid.”

What he found for Savion was a school of about 220 boys — all boys, deliberately — most of them black, most of them from Milwaukee, though the school is in Wauwatosa.

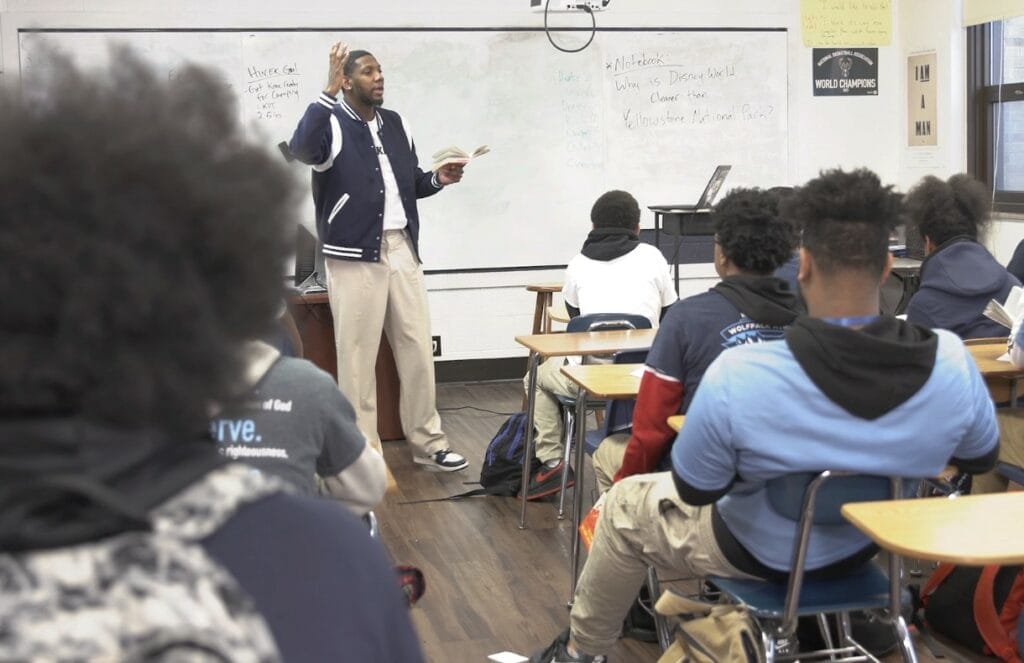

“We push these guys beyond their limits,” said Charles Smith. He teaches literature and, as does everyone in the school, brotherhood. New students earn the right to wear the school uniform through rites of passage, for example. Some are team-building games. Others involve each new boy telling of some difficult circumstance he thought would defeat him. It’s a lesson, said Smith, in how not to be isolated: “It’s OK to be vulnerable,” to trust God and the brothers among whom he put you.

“You should know everybody that you’re around, like everyone here is connected into one big thing,” said Frederick Johnson, a senior.

The biggest thing, in fact: “We’re preparing young men for the Kingdom of God,” said Smith.

“I would love every young man here to know that they are loved, created with a purpose,” said Kevin Festerling, who founded the school five years ago. If “they allow the same God who created this world and created them to name their identity and their purpose, those young men are going to be successful their entire lives.”

This means lessons in seeing what others need and figuring out how to provide it. Common to all students is the Nehemiah Project, a combination of shop class and discipleship that requires boys to identify someone else’s need, figure out a solution, and learn the skills to provide it.

Johnson made carts to hold the schools computers. Others built a garage for a woman across the street. Festerling tells of one student who wanted to design a bicycle motor because he was frustrated by the 90-minute, three-bus daily journey to school. Three months of effort yielded only failure.

“He then pulls me aside and says, ‘I think we should just bring driver’s ed to our school,’” said Festerling. “And then he wings a deal with the local driver’s ed institution. Now we’re on year five.” The young man is graduated and is succeeding in construction. “Without failure, we hardly know what we’re capable of,” said Festerling.

So the young men learn what they’re capable of through career days and internships at area companies, service projects at nearby schools, retreats at a wilderness camp up north. They opt for long drives or bus rides to reach Kingdom Prep because it’s what the boys need.

Beautifully, Wisconsin enables this by its long-standing school choice program that lets the boys’ parents — and for more than three-fourths of the boys, that means a mother having to raise a son on her own — take their state aid to the school they believe their sons need.

If only this were sustainable.

“Every time I meet a student and I’m recruiting,” said Festerling, “I get this heavy feeling of, ‘Oh, that’s another $5,000 debt we just went into.”

The state provides just over $9,000 per student. “Most good high schools that I study, they’re spending $14,000 to $16,000, minimum,” said Festerling. Statewide, district schools spend about $15,200 a student when you include cheaper K-8 grades. By law, Kingdom Prep parents cannot pay tuition atop the state’s money, so Kingdom Prep must rely on extensive fundraising.

It’s a barrier to parents and students who are “voting with their feet and with long bus routes,” said Festerling: “If every student who was enrolled in our school came with the same amount of money they would get at another district school,” he said, then none would have to be turned away for lack of fundraising capacity. “We could open up five more of these tomorrow.”

That not only is what parents say their kids need, it’s what Milwaukee needs. In the Milwaukee Public Schools, half the 8th-graders were incapable of reading last year. One in every four kids fail to graduate from high school. As Stewart put it, children need something better, academically and socially, than “when you wake up, somebody across the street from you got killed last night.”

“It’s becoming more and more important that we raise up generations of young people who know what’s right and wrong, who know what’s truth and what’s false,” said Festerling.

“If we don’t do that, they’re going to go off to these wolves who will eat them alive. And so I’m just so thrilled that school choice is giving guys who have a book called the Bible, that can preach the truth and the gospel, and if parents like that and want that, they’ll subscribe to it and send their kids.”

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields