Nation’s report card reveals impact of school shutdowns

Results of the test dubbed “the nation’s report card” went public this week, showing the degree to which pandemic-era lockdowns affected American children’s learning.

Right after scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, came out, Wisconsin’s chief public school regulator, state Superintendent Jill Underly, issued a press release headlined, “Wisconsin elementary school students buck national trends in ‘National Report Card’ release.”

This is not true: Wisconsin’s scores fell by every measure since the last time children took the test, in 2019, just as scores fell for every other state. Wisconsin’s scores fell more than some states and less than others, and generally they remained a few points above national averages, but they fell — they followed the trend, rather than bucking it.

That national trend was so bad, the New York Times called it “devastating.” No state saw gains in how well 4th– and 8th-graders perform at math or reading. In Wisconsin, 8th-graders in 2022 are most of a year behind where 8th-graders in 2019 were.

There are groups nationally that did buck the trend. The network of 160 schools, many overseas, operated by the Department of Defense for the children of active-duty military personnel saw no statistically significant drops in any subject or age group. State-level results weren’t available for Catholic schools but Catholic schools did comparatively well nationally, seeing smaller declines than national averages in some areas, with steady performance in 4th-grade math and gains in 8th-grade reading.

What also seems to have made a difference was whether many children in a state had access to in-person learning sooner — a measure of the harshness of a state’s pandemic lockdowns. Martin West, a Harvard academic and member of the board that governs the NAEP tests, put it this way Monday: “The best linear relationship between remote instruction and test score changes … is negative (and statistically significant), suggesting that students lost more ground on average where remote instruction was more prevalent — but the relationship’s strength is relatively weak.”

By the end of the 2020-21 school year, according to the American Enterprise Institute’s Return to Learn tracker, about 65% of Wisconsin public schools were back to in-person learning, among neither the best nor worst in the country.

If Wisconsin didn’t “buck the trend,” then what was true about the state’s NAEP results? Some key takeaways:

Wisconsin’s results fell.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction highlighted that Wisconsin 4th-graders’ scores didn’t fall much. Wisconsin was one of 10 states in math and one of 22 in reading in which the drop in 4th-graders’ scores wasn’t statistically “significant.”

But Wisconsin’s scores did fall, by 2 points in math and 3 in reading.

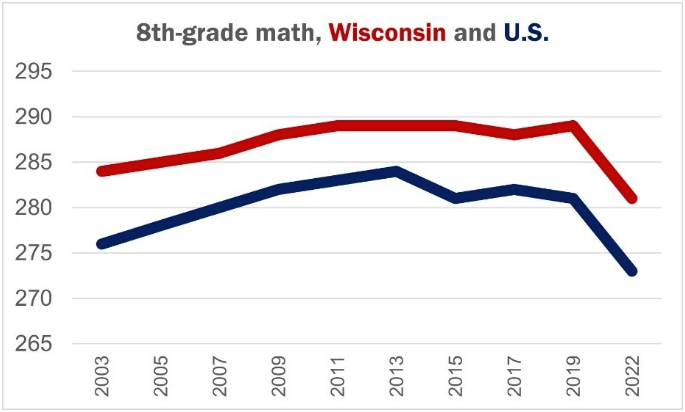

Much worse was 8th-graders’ performance — down 5 points in reading and down 8 points in math. The drops break what had been a slowly rising or steady trend. For 8th-grade math scores, the break in the trend of the past two decades is remarkable:

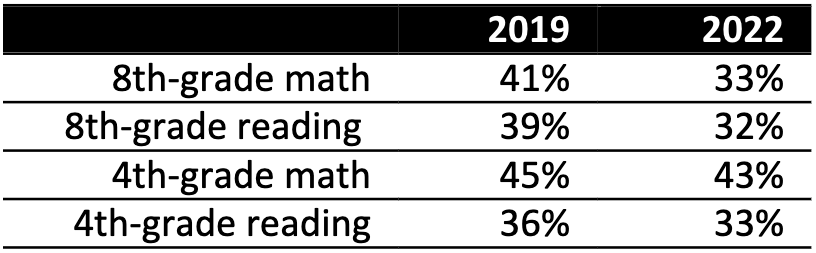

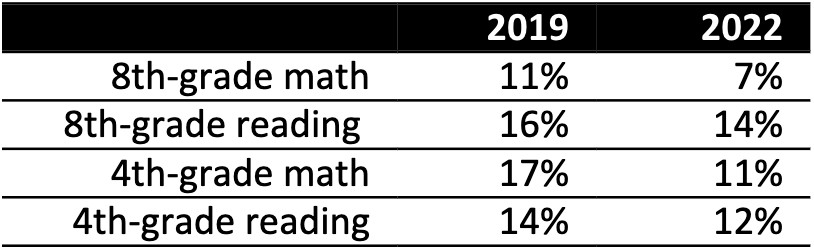

The tests also measure the degree to which students have mastery over age-appropriate material. The percentage of Wisconsin students scoring high enough to be regarded as proficient or better — that is, students who have “demonstrated competency over challenging subject matter”—fell sharply:

In sum, Wisconsin’s scores and proficiency levels fell on both subjects and in both of the two grade levels tested.

Even before the most recent drops, Wisconsin’s numbers were bad. They’ve worsened.

The Department of Public Instruction’s official statement hastily noted that Wisconsin’s “overall scores remained at or above the national average.” However, not only did those scores drop as other states did, but a large share of Wisconsin students cannot read or write well — and they couldn’t before the pandemic.

In the 2019 results — before the pandemic lockdowns — among Wisconsin 4th-graders, for example, only 66% of children tested as “above basic.” According to the NAEP administrators, that means that 34% of Wisconsin 4th-graders could not “determine the relevant meaning of familiar words using context within the same sentence or paragraph when reading literary texts.” Now it’s 37%.

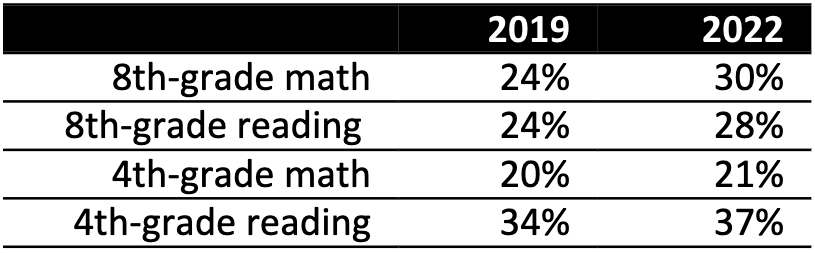

More broadly, children who score below basic do not demonstrate even a “partial mastery of prerequisite knowledge and skills.” The number of Wisconsin students scoring below basic in the last two assessments:

So, while 24% of Wisconsin 8th-graders before the pandemic were unable, for instance, to “solve real-world problems involving integers or fractions” or “find the distance between points,” now 30% cannot.

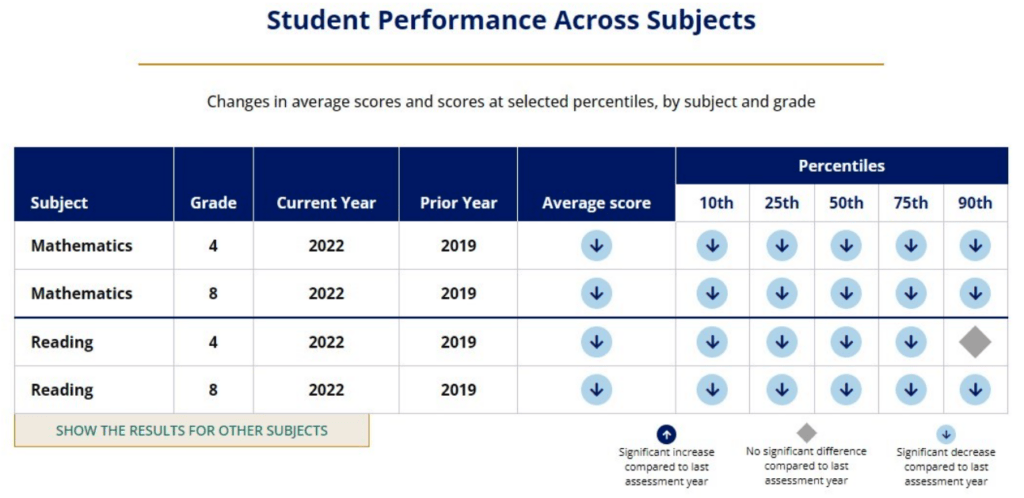

Wisconsin students’ performance fell nearly across the scale of ability.

It wasn’t just the weakest students who performed more poorly than their counterparts pre-pandemic, it was the strongest, too, with one exception. Students, for example, who were better at math than only 10% of other Wisconsin children at their grade level saw their scores drop significantly. So did children who were better at math than 90% of others.

It was, according to the federal Department of Education, only among the highest-performing students in 4th-grade reading that Wisconsin did not see a significant drop:

Milwaukee Public Schools’ performance fell too, and it is much worse than Wisconsin’s overall, as in previous years.

In the percentage of students who scored as proficient:

MPS was fourth- or fifth-worst among 25 large urban districts on both reading and math scores among 4th– and 8th-graders.

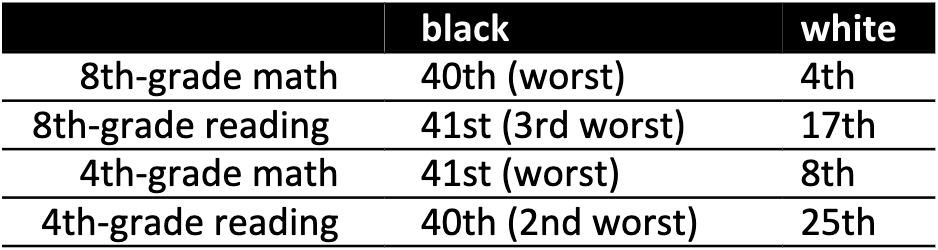

Wisconsin’s statewide gap between black and white students’ performance in both reading and math for both 8th– and 4th-graders remained the second-largest in the country, behind only the District of Columbia.

This is because while scores suggest that Wisconsin is at or above average among states in teaching white children to read and do math, it is among the worst of states in teaching black children. This is how Wisconsin’s scores for these groups of children ranked among states or, for black children, among the states where the federal government released figures:

This is likely related to Milwaukee Public Schools’ endemically poor performance, though analysts differ on the relationship of cause and effect: About 48% of all black students in Wisconsin’s traditional district schools are in the Milwaukee Public Schools. Just over half of Milwaukee Public Schools’ students are black.

It is worth noting that education results are not the only nation’s-worst racial gap for Wisconsin. No state has a greater racial gap than does Wisconsin in the number of children living in single-parent families. Of the 26 states for which the Annie E. Casey Foundation offers figures for black families, the highest percentage of children in single-parent families is in Wisconsin: 79% in 2019. By contrast, 23% of white children in Wisconsin were living in single-parent families, the 21st-lowest figure. Consequently, the gap between black and white children in Wisconsin, at 56 percentage points, was larger than in any other state. As former Wisconsin Secretary for Families and Children Eloise Anderson, a Badger Institute visiting fellow, pointed out recently, evidence abounds that children living in single-parent families face longer odds in school.

Wisconsin’s black-white gap, however, does not seem to be a proxy for income levels. NAEP’s results can be grouped by whether a child is eligible for free or reduced-price lunch or not — a customary measure of poverty or middle-class status. Wisconsin’s gaps in performance between these groups was about average among states.

Will a little more money make it right?

Underly and Gov. Tony Evers have proposed increasing public-school funding by $2 billion in the next biennial budget.

For comparison, Wisconsin school districts spent about $12.6 billion in the 2020-21 school year. That was up about a billion dollars from $11.6 billion four years previously, in the 2017-18 school year, or about 3.5% more after accounting for inflation. But because public-school enrollment has been falling, that’s a 7.6% increase in funding, after inflation, on a per-pupil basis.

What is more, Wisconsin’s school districts were allocated about $2.4 billion in federal pandemic relief as part of three massive “stimulus” bills. As of Aug. 31, about $1.9 billion — or 79% — was as yet unspent by school districts, according to the federal Department of Education.

Given the difficulty that districts — like other governments in Wisconsin — seem to be having in finding things to spend the federal emergency aid on, it is unclear how they would use any additional funding to make a difference in children’s performance. This is especially so in light of the difficulties many schools are having finding enough teaching staff. For example, the Milwaukee Public Schools, which lists more than 200 openings on its job site, is now using teachers not in classrooms but conducting lessons by video to children sitting in classrooms because it cannot find enough teachers.

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited