When even a city built around commuting by train can’t win back riders, it’s a warning to Milwaukee

Minnesota just last month finally pulled the plug on commuter rail line that “never lived up to its aspirations,” according to the head of the agency running it.

The lesson cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. Wisconsin, just by observing, can learn for free.

The Northstar line, with double-decker passenger trains from suburbs into downtown Minneapolis, cost $18.6 million just to operate this year, all to carry an average of 428 weekday riders by this summer. The agency running the trains said each ride in 2023 required a $116 taxpayer subsidy. That was up from $19.39 a ride in 2019, the pre-pandemic days when the trains carried an anemic 2,700 people a day, well below planners’ predictions.

COVID and riots in 2020 tanked what traffic the trains had: Ridership dropped 95 percent. “With the rioting and the dangers of working downtown the question then becomes ‘How many employers will stay?’” said one local official at the time.

Half a decade later, recovery was scant. After observing that Minnesota trains — distinct and separate from its inside-the-cities light-rail lines — covered less of their costs by fares than any other commuter rail system in America, an official of the metropolitan government told lawmakers, “There is no customer base for Northstar, nor will there ever be. But more importantly it’s taking money away from transit systems that could use that.”

For Wisconsinites, it’s not just antics in the next-door progressive circus. It’s a warning.

That’s because in metro Milwaukee, train enthusiasts and government planners keep inserting commuter rail into their four-color printable-pdf dreams.

In 2024, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation was chasing federal bucks to revive the idea of commuter trains from Kenosha via Racine to Milwaukee. Buying trains and getting existing tracks up to scratch could cost nearly half a billion bucks, never mind operating subsidies. Just penciling out the numbers required a $5 million federal grant.

This so-called KRM line has been touted since the 1990s, offering the dream of a 53-minute train trip that would take 45 minutes by car — but by train, see? It’s still there in the Southeast Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission’s “Vision 2050” along with hallucinations of another line to Oconomowoc, with little branches into Waukesha and Milwaukee’s north side.

Metro Milwaukee has less than half the population of the Twin Cities. Downtown Milwaukee, impressive as it is, lacks the skyscraper density of Minneapolis. One wonders what revolution in Wisconsinites’ preferences for where to live and to work will make commuter trains feasible in Milwaukee where they weren’t in Minneapolis.

Supporters disappointed at Minnesota bailing on the romantic dream of being a train town argued that 15 years wasn’t a long enough experiment, and that when ridership plummeted in 2020, service was cut from 72 trains a week to 20.

Fair enough. Fortunately, Wisconsin has another example to look at. How’s it going, Chicago?

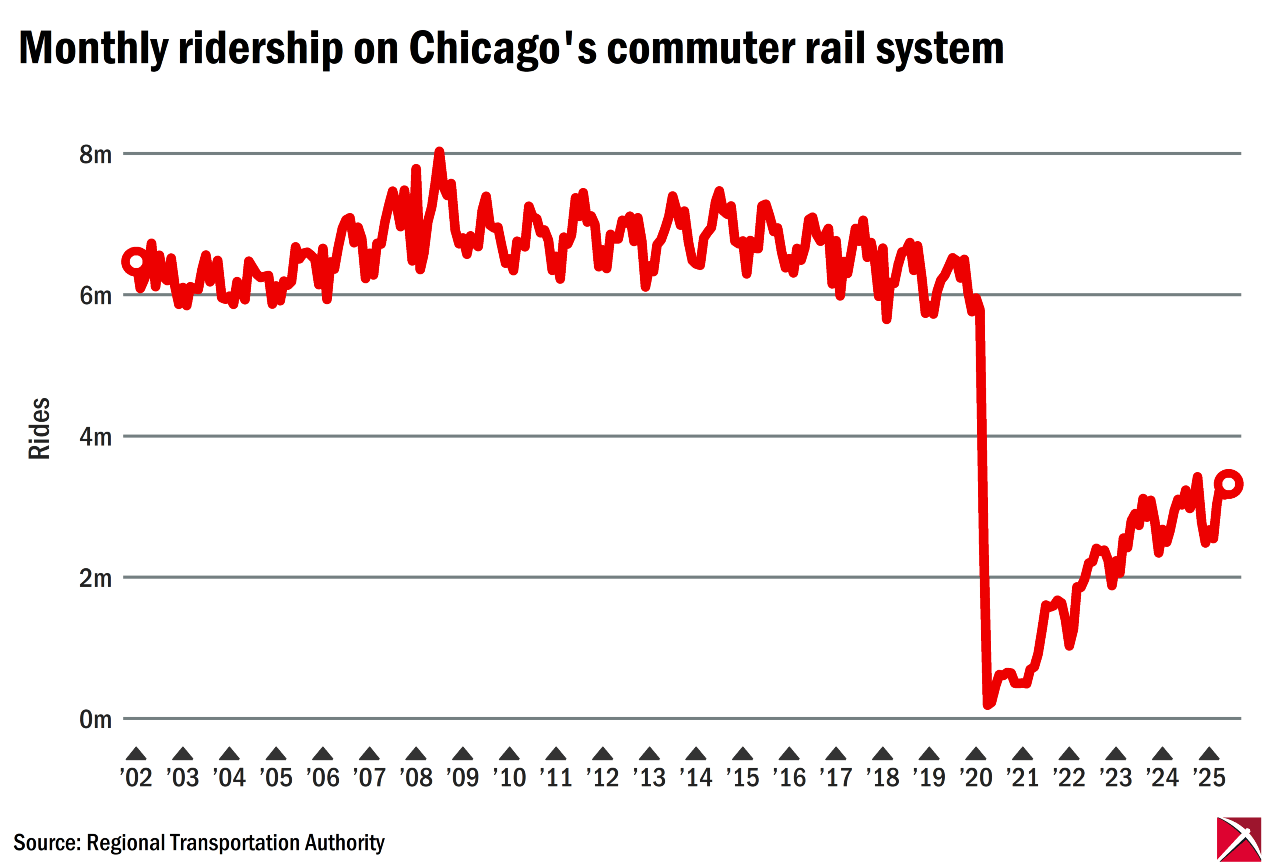

Wretchedly. Five years past the pandemic, ridership on Chicago’s 11-line commuter rail system, Metra, had by last year recovered to about half its 2019 figure, and the increase in monthly ridership was flattening. The Regional Transportation Authority, which also runs buses and Chicago’s separate “L” rapid transit system, was begging taxpayers for $1.5 billion to stave off insolvency.

Chicago’s example is all that Minnesota’s isn’t. It’s a place where commuter trains have been running since the days of steam, with old suburbs built around tracks leading to a downtown where for more than a century lawyers and bankers and wheat-futures traders have commuted by rail.

“Build it and they will come,” say rail advocates. Chicago long ago built it — and since 2020, they’ve stopped coming.

Dylan Sharkey of Illinois Policy, a research organization tracking the system’s fiscal woes, spoke to me of his personal observations as a transit commuter to a downtown office: The density of people and the shops or restaurants that rely on them remains depressed. In his view, hybrid or remote work is first among the reasons.

“Fridays are a ghost town compared to other days of the week,” he said.

It’s not that Chicago’s running fewer commuter trains. Metra is back to pre-pandemic levels of service, Sharkey notes: 665 weekday trains by the end of 2023, nearly matching the 687 weekday runs in January 2019.

Trains they’ve got. Riders, not so much. Rail, it turns out, is really efficient at moving a lot of workers in and out of downtown — a task no longer in so much demand, including in Milwaukee.

Meanwhile, Minnesota’s non-driving commuters aren’t out of luck. Authorities are substituting express buses on the route — one every half-hour, instead of only four a day, at one-sixth the cost to taxpayers. Bad for rail romantics, perhaps, but practical for riders.

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute.

Any use or reproduction of Badger Institute articles or photographs requires prior written permission. To request permission to post articles on a website or print copies for distribution, contact Badger Institute Marketing Director Matt Erdman at matt@badgerinstitute.org.