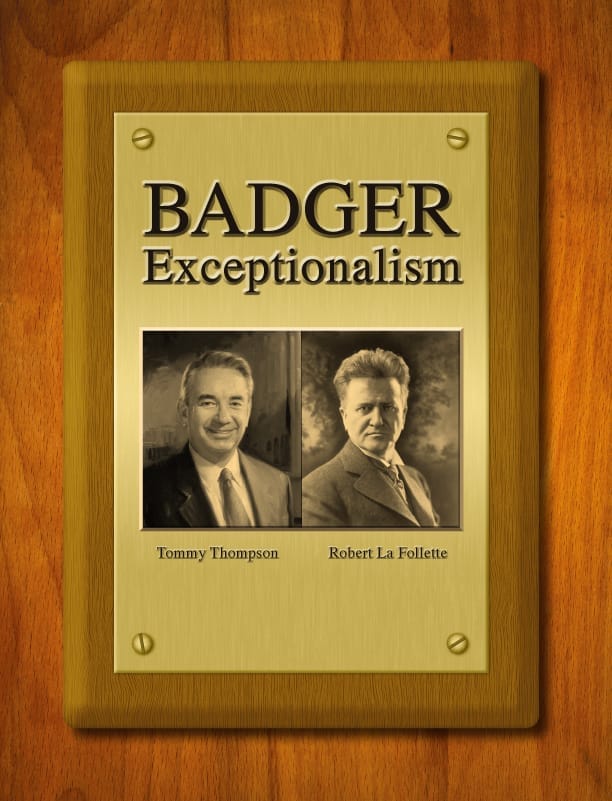

From open primaries to school choice, Wisconsin has led the way for the nation

By Warren Kozak

What is it about big ideas and the state of Wisconsin?

The state doesn’t have the largest population — it ranks 20th out of 50. It’s not the wealthiest — Wisconsin’s median income puts it 21st from the top. And it’s not even that big — again the state in square miles is close to the exact middle at 23 (and well behind its larger neighbors, Minnesota, 12, and Michigan, 11).

Wisconsin is pretty much near the middle of everything. It’s even situated close to the middle of the country.

But for some strange reason for over the past century, Wisconsin, that middle-of-everything state, has also been the incubator of some of the greatest political reform ideas in the United States. Let’s call it Badger exceptionalism. In fact, many of the most original concepts to benefit the common man since the dawn of the industrial revolution began not in Washington, D.C., or California, New York or Massachusetts. They started right here, in places like Madison, Milwaukee and little Primrose.

When people think of Wisconsin’s big ideas, they first think of the Progressive movement that took hold in the beginning of the 20th century. There is one name always associated with the movement — Robert La Follette. The Progressive tradition that La Follette championed continued for the next 70 years with the “sewer socialists” who helped run Milwaukee from the 1900s into the 1950s, right up through Sen. Gaylord Nelson and his environmental activism. Earth Day, one of Nelson’s lasting legacies, is not only still observed, it seems to grow bigger every year.

But over the last 20 years, a sea change has taken place in Wisconsin. Although the state has continued its tradition as ground zero for the big idea, it is the conservatives who have grabbed the intellectual high ground. And if the name La Follette defines the early reformers, Tommy Thompson’s 14 years as governor seems to be the starting point of Wisconsin’s new reformers.

Major new concepts like welfare reform and school choice began in Wisconsin under Thompson in the 1990s and then took hold throughout the country. The ground-breaking ideas have continued with a new wave of younger Republican conservatives — Scott Walker’s fight to break the hold of public sector unions in order to reverse huge unsustainable deficits and the celebrated fiscal policies of a congressman from Janesville, Paul Ryan. It doesn’t end there. The new chairman of the Republican National Committee, Reince Priebus, also comes from Wisconsin.

Actually, collective bargaining offers the greatest example of the massive switch that we’re talking about. Wisconsin was the first state to offer collective bargaining rights to public employees in 1959, and a little over half a century later, in 2011, Wisconsin became the first state to take on the growing strength of public employee unions by doing away with it.

When did Wisconsin’s intellectual switch from its liberal tradition to the conservative side take place? Was there one moment or was it personality driven? Or did it just evolve over time?

To answer those questions, a brief history of the state Republican Party is in order along with a closer look those two individuals — Robert Marion “Fighting Bob” La Follette and Tommy George Thompson — Wisconsin governors who served about a century apart.

At first glance, La Follette and Thompson may appear to be polar opposites on the political spectrum. But a closer look reveals they have more in common than most people would imagine.

La Follette was born in a log cabin (for real) in Primrose in southwestern Dane County five years before the Civil War. In college at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he was deeply influenced by its president, John Bascom, who stressed morality, ethics and social justice. This is part of the “Wisconsin Idea” — the state funds the great university system and in return the university gives back to the state graduates who improve its health and its agriculture and who offer great ideas on public policy that improve the lives of its citizens. Two of its leading proponents, Bascom and Charles Van Hise, are memorialized by signature buildings on the Madison campus.

As an aspiring politician, La Follette championed women’s suffrage and immigrant rights. He was elected to Congress for three terms in the 1880s. But La Follette didn’t really make his name until he lost the race for his fourth term and returned to Madison, where he practiced law.

“It’s important to remember [when comparing the two movements] that La Follette and the early Progressives were also Republicans,” observes Mordecai Lee, a former Democratic member of the state Assembly and state Senate and now a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

“It was the Republican Party that championed the end of slavery and fought for equality, fairness and good government reform,” says Lee.

But by the 1890s, things had changed and a split had developed within the state Republican Party. The opponents of the early GOP Progressives were the “Stalwarts.”

“Those were the Republicans who controlled the party,” explains Lee, “The timber barons, the beer barons, the guys at the country clubs with the cigars.”

La Follette fought the Stalwarts, first with an open primary. Up until then, the moneyed interests chose the candidates. The Progressives demanded a more democratic system of choosing leaders and fought for the open primary that we have today. This made Wisconsin one of the first states to adopt the primary system. As much as New Hampshire prides itself in always having its primary first, the concept of the primary was actually invented in Wisconsin in 1903.

In true populist fashion, La Follette traveled throughout the state speaking against moneyed interests — especially the railroad barons — and for more direct democracy. He also wanted and eventually established state regulatory control over utilities and other monopolies.

La Follette’s campaign paid off. He won the governorship in 1900, giving speeches in 61 counties from the back of a buckboard and launching a political career that lasted the rest of his life.

As governor, he ended the policy of free railroad passes for all state legislators and fought for the first workers compensation system, minimum wage, women’s suffrage and progressive taxation.

But with less than five years in office, La Follette left the governorship in 1906 and headed to the U.S. Senate, where he remained until his death in 1925. La Follette’s policies then went national, international and slightly off the rails. He was seen by many — not just conservative Democrats — as extreme.

Ultimately, La Follette broke with the Republican Party after strong disagreements with another Progressive, Theodore Roosevelt (who called La Follette a skunk and said he ought to be hung). La Follette’s vehement opposition to the U.S. involvement in World War I made him one of the most hated men in America. He formed the Progressive Party and was its candidate for president in 1924. He carried one state — Wisconsin.

Throughout his years in Washington, La Follette fought to end what he called “American imperialism.” He advocated for stronger laws for labor unions, the outlawing of child labor and keeping America out of any future wars.

His popularity in Wisconsin never waned, as evidenced by the fact that he won every election. Subsequently, almost any candidate with the La Follette name was assured some political office.

Given his record, and the political news Wisconsin has been making recently, it would appear that there has been a huge shift in the state’s attitudes. Or does it?

“It is really a continuum of the same thing,” says James Klauser, who served in Thompson’s administration in the 1990s and is board chairman of the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, which publishes this magazine.

“What’s changed are the definitions.”

Klauser suggests that it is wrong to use terms like liberal and conservative.

“Both of these movements — the Progressives in the early 20th century and conservatives in the 1990s — were advocating for the benefit of the individual against the controlling interests.”

By the end of the century, it was the controlling interests, he points out, that had changed. And this is where Tommy Thompson enters our story.

“In one case, welfare had reached a point of excess and it had to correct itself,” says Klauser. “Those who defined themselves as needy were getting greater benefits than those who were not.”

By the 21st century, the public employee unions had reached a point where the benefits of everyone from teachers to bus drivers were higher than many in the private sector. This saddled the state with unsustainable deficits.

“Things weren’t working, and they had to be fixed,” says Klauser. Like La Follette in his early days, Tommy Thompson in the 1990s was an outsider fighting against the status quo.

In the case of school choice, another correction had to be made. School systems in parts of the state weren’t doing their job of educating, and the state Department of Public Instruction was not open to Thompson’s new ideas. When school choice was passed and about to be implemented, a Dane County judge stopped it the day before it was set to go in place. This turned out to be a huge public relations debacle for the Democrats.

“We demonstrated that conservative reformers cared more about kids than liberal Democrats,” explains Scott Jensen, Thompson’s former chief-of-staff and a former Assembly speaker.

Thompson’s impact on politics in the state during the 1990s was huge, and it inspired a new class of younger Republican politicians, much the same way that young people who watched Ronald Reagan a decade before were inspired.

“Tommy Thompson captured the imagination of the country with school choice and welfare reform,” says Jensen.

Jensen remembers starting his days with breakfast at the governor’s mansion at 7:30 every morning and finishing the day with a phone call with the governor near midnight.

“Tommy’s greatest strength — and what drove me nuts — was that he would talk to a huge number of people. He talked to everyone from all sides and all walks of life.” Jensen remembers Thompson inviting welfare mothers into the mansion to listen to their problems and, perhaps more importantly, their hopes and dreams — what they hoped to accomplish in their lives.

“It was what I was taught at the Kennedy School [of Government at Harvard University] about how government — good government — should operate,” says Jensen.

In that way, Thompson believed in government. More specifically, he believed in government that could fix things that were broken and help people make better lives for themselves — again, an updated version of the Wisconsin Idea.

“There was no ta-da moment with welfare or school choice,” Jensen observes as he looks back on his years with Thompson. “We tested both of these out in different counties, and we pored over the data. We’d toss out parts that weren’t working and keep the elements that worked.

“Our ta-da moment came later when it was implemented and it worked.”

“Tommy Thompson fundamentally saw government as something to help people, but government wasn’t doing that,” recalls Linda Seemeyer, who worked for Thompson and later worked for Scott Walker when he served as Milwaukee Country executive. “An example of that was the Family Care Act, which allowed people to care for their relatives themselves and close institutions. This way, they received better care and it cost much less.”

“Tommy Thompson was a Republican in the old tradition,” says Charlie Sykes, the talk show host on WTMJ and editor of this magazine. “He is different from today’s conservatives. He worked with what he had. He did things incrementally. He was patient.”

So if Tommy Thompson was the catalyst for the new progressives and the next generation of young Republican shakers like Scott Walker and Paul Ryan, that still doesn’t answer the question: Why Wisconsin?

“Maybe it’s because it’s so evenly divided,” says Seemeyer. “People are nice and friendly and have to listen to each other.”

“There is something about our culture,” notes Sykes, “and perhaps the role the earlier Progressives served as a precursor, but there is definitely a tradition of hearing out the other side — although you wouldn’t have known that in the recall election.”

When it was pointed out that the country is pretty evenly divided and people are just as nice in Iowa, Seemeyer agreed. “But maybe it was as simple as two men [Thompson and Walker] at the right place at the right time, one inspired by the other and a public willing to listen to both sides and make up their mind.”

Add La Follette to that list.

“So much has to do with events and timing,” says Jeff Mayers, the president of WisPolitics.com, an online political news service based in Madison.

“Some of it is event-driven, and some of it was driven by ambitious politicians — and in this case, ambition is not a bad thing.”

The timing that Mayers refers to has to do with the fact that there was money available in the 1990s to actually accomplish these big ideas.

“After Tommy left to go to Washington, Doyle came in and these were tough times,” Mayers points out. “So he was in a holding pattern trying to protect programs. It was a different time and they were different politicians.

“Thompson was also helped by Democrats like Milwaukee Mayor [John] Norquist, who supported school choice and welfare reform as well,” says Mayers. “This gave it national attention, and it was picked up by President Bill Clinton.”

“The concept of Tommy Thompson being at the right place at the right time is correct,” says Klauser. But he strongly disagrees that Thompson had national ambitions. “He had no thought on national programs. His focus was purely on the state.”

Still, why Wisconsin?

“Well,” says Klauser, “If you are asking how do ideas start … how did [German Chancellor Otto von] Bismarck come up with these early ideas of social security and healthcare? The apprenticeship program began in Germany and was adopted here. We borrowed these ideas from Germany, which were brought over by our German ancestors.

“There is no easy answer to this,” continues Klauser. “It’s a confluence of time and events.”

UWM’s Lee reminds us that a lot of La Follette’s support came from the rising middle class, small farmers and Scandinavians.

Support for the Republican agenda in the 1990s was driven by Thompson. The reforms to welfare and school choice were logical, since they were adopted by both parties. But there was one more factor that pushed it — talk radio.

“Conservative talk radio found a successful economic niche,” Lee says. “The liberals couldn’t — Al Franken [the comedian and former talk show host on liberal Air America] had to run for the Senate to find a job.”

But conservative talk radio had a huge influence, especially in the southeastern quadrant of the state — so much so that it divided the Republican Party in the state, with the GOP in the north being more moderate than the Republicans in the south.

“That was true to some extent,” observes Scott Jensen. “But by the 2010 election, the rest of the Republicans in the state had come to the same conclusions as those in the southeast.

“The original program of the early reformers was individual citizens against the power of big business,” says Jensen. “The conservative reformers still fight for the individual citizen, but now it’s against the power of big government.

“At the heart of what Tommy Thompson was trying to change with welfare reform and school choice was to empower people over government,” he says. “To let people who were shackled by welfare free themselves from government. To educate kids and give them futures, because they weren’t being educated by the system that was in place.”

The citizens of Wisconsin have been the beneficiaries of two of the greatest movements in this 236-year-old democracy. So has the rest of the country. Robert La Follette successfully worked at making lives better as the governor of Wisconsin. Whether it was an updated version of the old Progressives as Jim Klauser suggested or something completely different, Tommy Thompson did the same thing a century later.

And now, a younger generation of Republican transformers is writing whole new chapters of the state’s history books … and the country’s as well.

Wisconsin native Warren Kozak is a frequent contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page and the author of the recently published ebook, Presidential Courage: Three Speeches That Changed America.