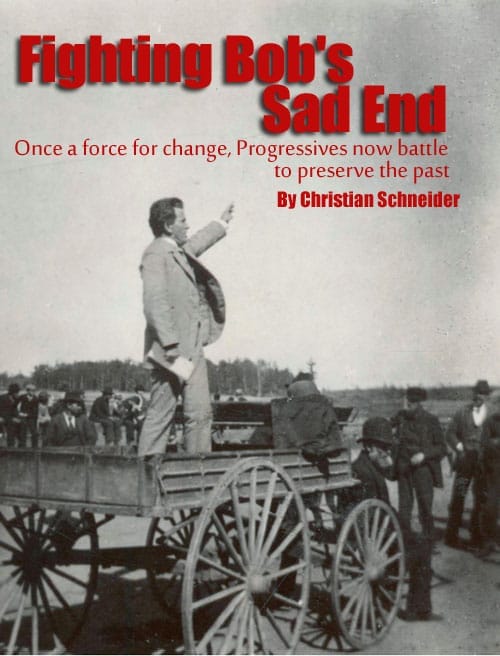

Wisconsin historical Society Photo 3562

In the summer of 1897, Wisconsin gubernatorial candidate Robert M. La Follette hopped on to the back of a farm wagon at the Oshkosh fairgrounds to give a speech. The wagon was positioned on the racetrack, and when La Follette started speaking, the starting bell began drowning him out. Soon, he saw horses running right at him, and he pulled the wagon off the track. When they had passed, La Follette rode the wagon right back on to the track and threatened to keep talking for the rest of the day if he wasn’t allowed to finish his speech.

“The supreme issue, involving all the others, is the encroachment of the powerful few on the rights of the many!” he thundered in conclusion.

Of course, La Follette was talking about both business interests and the political machines, which, in concert, routinely bought and sold legislation in smoky back rooms.

“I believed then, as I believe now, that the only salvation for the Republican Party lies in purging itself wholly from the influence of financial interests,” wrote La Follette in his autobiography. But after 112 years of La Follette’s Progressive vision coming to fruition, it is worth considering: What now constitutes the state’s most powerful “financial interest”?

Government unions are a good place to start. While things like “public sector unions” and “women voting” were still dreams when La Follette was governor from 1901 to 1906, government unions now spend more than any other single group to affect campaigns in Wisconsin. And this spending is rarely intended to forge a new Progressive vision in Wisconsin. It is generally used to protect what the unions already have.

“Progressivism” used to stand for clean, honest government. Today, it merely means, “Keep your hands off my benefits.”

One of La Follette’s many sworn enemies, Republican Gov. Edward Scofield, dismissed his rage against the party “machine” in 1900, predicting that government would one day become the same type of machine La Follette purportedly loathed.

Branding Fighting Bob’s avowed hostility to political machines as farcical, Scofield warned that if elected, La Follette would “build up the most complete and personal machine in the history of the state.”

And in 2012, it was that machine of 284,963 Wisconsin state and local government employees and their spouses who sought to recall Scott Walker from the governorship, thereby attempting to overturn a popular election held little more than a year earlier. (The recall election is also a product of the Progressives, having been added to the state constitution in 1926 by La Follette loyalists.)

In his time as governor, La Follette could not have imagined the breadth and scope to which government would grow in Wisconsin. In 1899, the state spent $4.7 million on everything, from public education to universities, to the court system, to “insane county asylums.” (About 32 percent of all government was funded by railroad license fees.) That amounts to $121.5 million in 2012 dollars, or $58.73 per capita. This year, Wisconsin state government is scheduled to raise and spend around $32.4 billion, or $5,696.52 per capita.

The imposition of the nation’s first income tax in 1911 — and the commensurate revenue it produced — sparked an inexorable 100-year march toward government as the state’s largest employer:

Even in the past 35 years, government has become the primary employer for more and more Wisconsin citizens. Today, 71,552 more Wisconsinites are employed by state and local governments than in 1976, an increase of 33 percent.

All those new government jobs came with a cost; especially once Democratic Gov. Gaylord Nelson signed the nation’s first law allowing public sector collective bargaining in 1959. Within a decade, unionized teachers were participating in illegal strikes to force higher salaries and better benefits. As a result, Wisconsin passed a new landmark mediation-arbitration law that virtually guaranteed that teacher compensation couldn’t be cut.

Geographical-pattern bargaining strategies were perfected by the teachers union, forcing school districts to match the gaudy compensation packages passed in comparable districts around the state. By 2011, state government employee salary and benefit packages averaged $71,000. In the Milwaukee school district, average employee compensation soared to more than $100,000 per employee — for nine months of work.

In recent decades, the growth in the cost of government has exceeded the growth in the state’s economic output. In 1980, state spending accounted for 12.9 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. By 2010, that number had grown to 16.2 percent of Wisconsin’s GDP:

The financial cost to taxpayers is just the beginning. Bob La Follette stood on hundreds of stages, wagons and soapboxes upbraiding railroads for their monopolistic practices. The railroads, he argued, preyed on the public, soaked customers for excessive fees, then turned around and bought legislators with campaign contributions.

But now that party standard-bearers are picked through primary elections (thanks to “Fighting Bob”) and not backroom dealings, the most powerful monopoly that still exists can be found in the state’s public education system. Public school teachers pay millions in dues to elect politicians who vow to kill any legislation that allows parents choices in where to educate their children. “Choice” and “charter” schools are pejorative terms in the hallways of the teachers union headquarters. Mention “virtual” schools and they might throw you out a window.

Again, “progressive” has simply become political-speak for “status quo.”

Often times, the aims of the teachers unions directly conflict with the needs of their own students. When Gov. Scott Walker introduced his collective bargaining reforms in February 2011, Madison-area teachers staged a “sick out,” walking off the job for four days. Teachers in other districts around the state followed suit, ignoring the state law against coordinated work stoppages.

Other union rules make it nearly impossible to fire troublesome teachers. In 2006, the Cedarburg School District attempted to fire a teacher who had been caught viewing pornography on his work computer; the union sued, and an arbitrator granted the teacher his job, plus back pay with interest. Eventually, the firing was upheld, but only after great expense to the district.

Similarly, the Middleton-Cross Plains School District last year tried to fire a teacher who had been viewing and sharing pornography from his work computer. Again, the union sued, and this time, the teacher was awarded his job and $200,000 in back pay. In its failed attempt to fire him, the district estimates it spent $300,000.

Of course, education’s union-friendly framework is represented legislatively by the Democratic Party. And teacher unions are mightily focused on electing Democrats to positions of power. In the 2008 and 2010 election cycles, the political arm of the Wisconsin Education Association Council poured an estimated $3.6 million into electing Democrats to state office.

The investment paid off, as Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle battled school-choice measures, lifted the statutory cap on teacher salaries, and continued to increase school funding, despite driving the state into ever-increasing structural deficits.

The unions have dropped any pretense of bipartisanship. In 2003, facing a $3.2 billion budget deficit, Gov. Jim Doyle proposed eliminating the requirement that the state fund two-thirds of local school costs, and granted an increase of $26 million in general funds between 2003 and 2005. As expected, the teachers unions gave Doyle a pass, calling the budget situation “worse than grim,” conceding there would be “pain on the way to recovery.”

Republicans, who had gained control of both houses, believed that with such a paltry state-aid increase, school districts would simply pass the cost on to taxpayers. So the GOP shrewdly increased school funding by $88 million over what Doyle had proposed, along with installing a commensurate cap on local property taxes that could be loosened via public referendum.

Predictably, the state’s largest teacher union lost its mind. WEAC President Stan Johnson declared the Republican version of the budget would “return Wisconsin to the Ice Age” — as if children would be forced to ride mastodons to school. When Democrats propose increased spending, it’s because “every kid deserves a great school.” When Republicans increase spending, you’ll have a saber-toothed tiger chasing you to the mall.

Of course, the hyperbole continued to flow from legislators tethered on the union leash. Democratic Sen. Bob Jauch said he had “a hard time understanding the Republican compulsion to take a meat ax to the children of this state.” The Joint Finance Committee co-chair, Sen. Russ Decker, said the proposal was like “putting a gun to the head of public education and to students.”

In his 1994 book, The Art of Legislative Politics, former Assembly Speaker Tom Loftus, himself a Democrat, shrewdly explained that WEAC’s goal is no longer to push to expand its benefits; it is simply to protect the status quo it has built over decades of lobbying. Loftus quotes former WEAC head Morris Andrews, who justified lobbying the Legislature and governor heavily by arguing those are the entities that “can stop bad things from happening.”

Wisconsin Historical Society Photo 28020

In fact, being a Progressive in Wisconsin these days appears to mean you think politics began on the day Scott Walker introduced his collective bargaining bill. You have to condemn the evil, right-wing Koch brothers for funding Walker’s campaign to benefit themselves. You have to say things like, “Scott Walker is a liar because he never said he was going to eliminate collective bargaining during the campaign.”

It isn’t incumbent on you, as a Progressive, to learn that after two unsuccessful gubernatorial runs, Robert La Follette’s third campaign was funded almost entirely by wealthy U.S. Rep. Joseph Babcock, who thought bankrolling La Follette would catapult himself into the U.S. Senate. According to author Robert S. Maxwell, in La Follette and the Rise of Progressives in Wisconsin:

“La Follette also received valuable assistance from the leader of the congressional delegation, Joseph W. Babcock. This politically ambitious ex-lumberman had already served four terms in Congress and was seeking a larger field for his talents. He was quite aware of the disintegration of the Republican organization and sought to organize the machine to advance his own interests. Babcock was sure that his support of a La Follette ticket would be both popular and successful. It is probable that he thought he would be able to control the new governor and use the state organization to elevate himself to the senatorship.

“Events were to prove that he misjudged his candidate completely and vastly overestimated his own abilities, but during the campaign of 1900, Babcock’s financial assistance and organizing skill contributed greatly to its success.”

You aren’t expected to know that La Follette, in his 1900 campaign, completely changed course and positioned himself as a pro-corporate candidate to earn the approval of the public. When one supporter urged La Follette to talk about regulating railroad fees, La Follette bristled because of the backlash it might cause.

“We might, therefore, get a taxation law, but if we proposed also to push railroad regulation at that time and assert the power of the state to fix rates, the railroads would call to their support all the throng of shippers who were then receiving rebates,” La Follette recalled in his autobiography. Later, as governor, he would propose regulating railroad rates. (To Scofield, La Follette’s most bitter enemy, this “harmony” campaign was considered “a ruse and subterfuge of the radicals and Populists to gain power.”)

You are also supposed to forget the black marks of Progressivism: the virulently racist eugenics of La Follette’s handpicked president of the University of Wisconsin, Charles Van Hise, who once said, “He who thinks not of himself primarily, but of his race and of its future, is the new patriot.” You have to forget that Progressives played a part in foisting Prohibition on the nation, an unforeseen effect of which was people either blinding or killing themselves by drinking substitute alcohol made of chemicals such as paint thinner.

All that a liberal Wisconsinite needs to know about “Progressivism” is that it now means, “We like things exactly the way they are.” You must simply delude yourself into thinking government unions aren’t a “special interest.” But the lesson of the past 100 years is clear: Everyone has an interest in government; it’s just the amount of money that determines how “special” it is.

Christian Schneider is a senior fellow at the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute and a columnist for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel.