Mavis Roesch began teaching in the St. Louis Public Schools in 1967. Soon after, she moved to Milwaukee, teaching first at a private high school and then in the Milwaukee Public Schools. For the past 15 years, Roesch has taught at Rufus King High School, recently ranked by U.S. News and World Report as one of the top 200 high schools in the country.

“I care about young people and their future and the future of our city,” Roesch says with passion. “I believe that I make a difference in my students’ lives. I work to inspire them to do things they thought they couldn’t do. I believe that all children can learn — maybe in different ways and on different days, but I want to be there when it happens.”

And then Roesch, who runs King’s International Baccalaureate program, adds something that is already evident in her self-declared mission: “I do not work for a paycheck or benefits.”

Clearly, teachers like Roesch are not what ails MPS. Dedicated professionals like her are the reasons for academic success stories like Rufus King. Yet, paradoxically, she is soon to join the ranks of those who are at the root of MPS’ looming fiscal crack-up: Retirees.

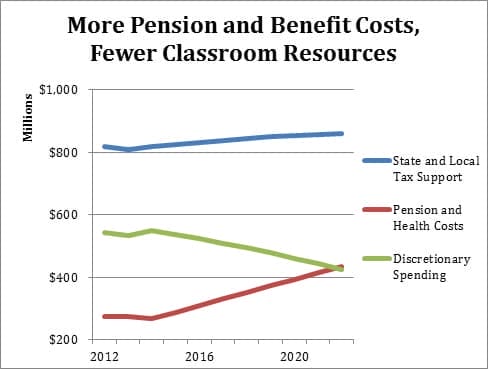

By 2022, the cost of MPS pensions and health benefits will absorb just more than 50 percent of the district’s state aid and property tax, up from one-third in 2012. More to the point, less than half of MPS’ state aid and local tax revenue will be available for teacher salaries, classroom materials, new technology and other educational needs. There is little MPS can do to stem this decline in discretionary spending. As shown on the following chart, it could be a death knell for the district.

The decline is driven primarily by the ballooning cost of retiree health benefits. Estimates put MPS’s unfunded liability at $2.2 billion. (See the WPRI study authored by Don Bezruki for details.)

Almost a quarter of MPS’ 9,300 employees are eligible for retirement and corresponding health benefits, and the district estimates that more than 1,400 employees will retire by 2015. This includes Roesch, who plans to step down in June 2013. She will be 67.

Logic suggests that the retirement of older employees with higher salaries should allow the district to save money by replacing them with younger, cheaper employees. However, this logic is undermined by the district’s need to continue paying for the health benefits of those retirees.

Soon MPS will be spending nearly as much on retiree health benefits as it spends to insure current employees. Any savings from the lower salaries will be offset by obligations to retirees.

In short, MPS is in the throes of a slow but inexorable budgetary meltdown. This prospect was already evident in 2004 when then-Superintendent William Andrekopoulous told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that fiscally the district was like a late-stage cancer patient facing death.

Harsh reality is that without a dramatic rethinking of how public education is delivered, tens of thousands of Milwaukee children will be stuck in a school system putting fewer and fewer of its resources into the classroom.

This is unlikely to improve academic performance in a district distinguished by its failure to educate its predominantly poor and minority enrollment. In 2011, only 10 percent of MPS pupils scored proficient in reading and math on the National Assessment for Educational Progress.

At 61.1 percent, the district’s four-year graduation rate lags significantly behind the state average of 87 percent. And graduating from MPS is no guarantee of future success. About 70 percent of MPS graduates attending the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee need remedial math education. Worse, less than 20 percent actually graduate from UWM after six years.

MPS’ financial problem is quite simple. The amount of revenue committed to retiree health benefits is growing faster than the district’s capacity to raise revenue from state and local taxes. Many difficult financial decisions, such as freezing salaries and increasing employee benefit contributions, have already been made. The forecast made for this WI story factors in the impact of these decisions.

There is plenty of blame to go around. Generations of school boards that saw the perils did nothing. State legislators for years increased education funding for the purposes of property tax relief rather than classroom funding. Governors and state superintendents did not use their bully pulpit to bring attention to the growing problem. But playing the blame game does nothing to deal with the tens of thousands of Milwaukee children stuck in a deteriorating school district.

The roots of MPS’ financial problem date to its 1973-’74 labor contract with the Milwaukee Teachers Education Association. The contract allowed retiring teachers to maintain the same health insurance plan they had as teachers, and it required the district to pay the cost of premiums up to the highest-cost plan offered in the year the teacher retired.

Today MPS employees can retire with lifetime health benefits for themselves and their spouses if they are 55 or older, have at least 15 years of experience and can show that they’ve used no more than 30 percent of their sick leave. (Teachers earn up to 12.5 days of sick pay annually; the maximum balance is 145 days.)

Several factors have combined to make this seemingly innocuous decision on retiree health benefits the cause of the district’s demise.

First, people are living longer, extending the amount of time health benefits must be paid. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, life expectancy has increased since 1970 from 71 to 78 years.

Second, in 1982, the district began offering a sweetener pension that was designed, according to MPS, “to incent retirements at a time when there was a surplus of teachers to avoid teacher layoffs.” This early retirement sweetener increased MPS’ retiree cost burden by decreasing the average age of retirees and extending the length of time retired teachers received health benefits. And that expense was magnified by the comparably higher cost of pre-Medicare health benefits for retirees under 65.

To its credit, the MPS board has said it will eliminate the second pension when the current union contract expires in 2013.

Third, the costs of health care have increased at a rate unfathomable in 1972: two to three times the rate of inflation over the past eight years, according to MPS board documents.

Fourth, and most damaging, MPS chose to use pay-as-you-go budgeting for retiree health care costs rather than setting aside funds annually for the cost of future retirees. As a result, it has no reserve to draw on as employees retire and begin racking up health insurance costs.

The next 10 years pose a nearly impossible challenge for MPS leadership. The combination of soaring health insurance costs and the fiscal impact of shrinking enrollment leaves the district in a death spiral from which it is unlikely to recover.

You can find the assumptions of my projections in the sidebar at the end of this article. I project that, under the most likely scenario for 2012 to 2022, state and local taxes for each MPS student will increase by 27 percent. However, because of declining enrolling, the overall increase in state and local tax money to the district will be only 5 percent. At the same time the cost of retiree health benefits will increase by a stunning 168 percent. MPS does receive program-specific aids, but that stream of state and federal aid cannot be counted on to offset the shrinking pot of general school-aid and property tax revenue.

Put another way, over the next 10 years, taxpayers will send more money to MPS, but significantly less money to MPS classrooms. In 2022, taxpayer support for the district is estimated to be $42.4 million higher than it is today, but the district’s discretionary spending (revenue not committed to health and pension costs) will be $118.5 million lower than it is today.

Fewer students. Higher overall public support but less money making it to the classrooms. Annual layoffs and program cuts. This is the untenable situation MPS faces over the next 10 years.

What can MPS do?

Pretending nothing is wrong is the easiest option. That would mean more and more money would go to benefits and pensions at the expense of classrooms. This would have dire consequences for the classroom and likely for enrollment. Consider that MPS’ own 2013 budget narrative lists as a top priority ensuring that “Every traditional MPS school in FY13 will have an art, music or physical education teacher in their school at least one day per week.”

This modest goal isn’t competitive with other schools. For example, Greendale Superintendent William Hughes tells me that his district offers “art twice a week, music twice a week and physical education three times a week” for grades K-5, and “daily art and music mainly on an elective basis” for grades 6-12.

Milwaukee College Prep, a charter school, has “art, music and physical education teachers at each campus every day,” says president Rob Rauh.

Lutheran Urban Mission Initiative, which operates four schools in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, offers “physical education twice a week for all the students,” and “music and art once per week,” says curriculum chief Charles Moore.

How can MPS attract students when its programming falls below the level available at competing schools? If MPS chooses the path of least resistance, its enrollment declines and yearly budget strains will only intensify.

Critics and reformers have called on MPS to make the difficult decisions necessary to offset the cost of retiree health benefits. The problem, however, is that MPS Superintendent Gregory Thornton and the MPS board have already made difficult decisions to rein in costs.

In November, the board voted to require employee contributions to fund from 7 percent to 14 percent of their health care premiums, depending on salary. The board also voted to introduce four furlough days as well as to institute a salary freeze in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

These changes, which begin when MPS employee union contracts expire in 2013, are projected to reduce the district’s unfunded liability to $1 billion over the next 30 years. However, as my calculations show, these savings may be insufficient and too late.

Of course, to save even more money, MPS could choose to increase employee health care contributions, cut rather than freeze salaries, or institute more furlough days. However, further decreases to employee take-home pay will make the district an unattractive place to work and only intensify the stress felt by teachers.

When I asked Roesch about the challenges facing MPS, she cited the expanded choice program, student behavior, “unconscionable class sizes” and attacks by the Walker administration on MPS and Milwaukee.

“I have never before felt such palpable stress among my colleagues as they contemplate the future of our state and our students,” she told me.

Increasing the burden placed on MPS employees, teachers in particular, is not a realistic solution to MPS’ fiscal challenges.

The “nuclear option” — bankruptcy or dissolution of the district — was floated in 2008 by the MPS board and more recently in 2010 by Milwaukee Alderman Bob Donovan. However, municipal bankruptcy would require significant changes to state statutes, and even then it is unlikely MPS would qualify for protection under federal municipal bankruptcy law.

That’s because MPS’ fiscal problem stems from liability costs, not insolvency, which is defined in the federal statutes as not meeting debt obligations or being “unable to pay its debts as they become due.”

MPS may be fiscally strained, but it’s not insolvent.

Another option is a state bailout where the district’s retiree health care obligations are transferred to the state. While this would certainly improve MPS’ fiscal trajectory, the transfer of a $2 billion-plus obligation to state taxpayers seems unlikely.

What about more public aid? Alternative fiscal scenarios show that even unprecedented public investment in MPS through the state funding formula and losing fewer students to choice schools will not solve the fundamental problem, only delay the inevitable.

Say for example the annual per-pupil revenue limit grows by $500 annually, creating a 38 percent increase in per-pupil investment in MPS over the next 10 years. Still, total health care and pension costs would account for almost half (46 percent) of the state and local tax revenue sent to MPS.

MPS does have an apparent stealth strategy.

Historically MPS advocates have complained that private and independent charter schools are cutting into district enrollments. However, there appears to be an uptick in MPS’ enthusiasm for non-district classrooms, as long as the students in them are counted as MPS pupils.

In 2011-’12, 4,326 MPS students attended non-union charter schools in Milwaukee. One-year prior, only 2,471 MPS students attended non-union charters. MPS employees do not staff non-union charter schools, but the students in them are counted for state aid purposes.

The growth appears to be part of a deliberate strategy to increase the use of non-MPS providers to educate students included in the MPS school aid count. Such arrangements can give non-MPS providers additional funding, while also leaving MPS with more money to set aside for its unfunded liability.

Consider the case of Milwaukee College Preparatory.

The school, whose original campus was chartered by UWM, now enrolls 652 students in two non-union MPS charter school campuses.

MPS offered incentives for the school to come under the MPS umbrella. This included added per-pupil funding above the standard payment of $7,775 in return for meeting specific performance goals and for providing expanded hours of instruction. More to the point, the agreement also generates new revenue for the district because it keeps a chunk of the new state aid for its own purposes.

For this approach to be a long-term fiscal solution, MPS must dramatically increase the number of students served in independent, non-union schools. However, a 1999 memo of understanding between MPS and the Milwaukee Teacher’s Education Association limits the number of MPS students to be served by non-MPS providers to 8 percent of total district enrollment. Pursuing this strategy will require scrapping this agreement.

MPS is dying.

As Mavis Roesch and thousands of other MPS employees move onto retirement, the pace of the district’s fiscal deterioration will increase exponentially. More money and improved leadership are not enough to save MPS. Cutting pensions and heath benefits earned in good faith by MPS employees like Roesch will likely not hold up to a court challenge.

Only a dramatic restructuring of how public education is delivered to Milwaukee students can stem the district’s fiscal decline. Failure to act is an implicit choice to leave Wisconsin’s largest and most troubled school system with not only the state’s most-disadvantaged students, but with fewer dollars to invest in teachers and classrooms.

Sidebars:

Mysteries of the state funding formula revealed

Wisconsin school districts are permitted to raise a set amount of revenue from state aid and local property taxes annually. That amount is called their revenue limit. Here’s how the formula works:

1. The legislature sets in the state budget the annual increase in the per-pupil revenue limit. That number is added to the district’s per-pupil revenue limit from the previous year.

2. The three-year average of a district’s enrollment is determined.

3. The total amount of revenue a district can raise from state equalization aid and the property tax levy is determined by multiplying the per-pupil revenue limit by the three-year rolling average. If a district had a per-pupil revenue limit of $10,000 and a year enrollment average of 500, for example, the district could raise $5 million.

4. The property wealth of a school district is used to determine the share of allowable revenue that comes from state equalization aid and the share that comes from the local levy. The poorer the district, the more state aid it receives. That’s the “equalization” principle at work.

5. A district can also choose to set its tax levy below the maximum allowable amount, or to go to referendum if it wishes to exceed its maximum allowable levy.

— M.F.

MPS 2012, at a glance

Total Staff: 9,306

Teachers: 5,044

MPS Sites Enrollment: 80,098

Total Budget: $1,188,160,523

Property Tax Levy (Operations Fund): $275,843,911

General Equalization Aid: $554,850,459

Federal Categorical Aids: $183,531,554

State Categorical Aids: $29,691,425

Private Grants: $7,060,441

Source: MPS fiscal year 2013 proposed budget

Calculating a financial meltdown

Under the most likely scenario for the years 2012-’22, the state aid and property taxes going to MPS will increase by only 5 percent, while the cost of retiree health benefits will climb by 168 percent. Here are the assumptions behind that scenario:

- Beginning in 2014, annual MPS increases return to their 2000-’11 average growth rate of $285 per pupil. (Per-pupil revenue limits were cut statewide by 5.5 percent in 2012 and set to increase by $50 in 2013.) This would raise MPS’ per-pupil revenue limit from $9,726 to $12,341 over 10 years.

- The average annual decline in MPS’ three-year enrollment average for the past 10 years, 1,437 students, continues until 2022. Over 10 years this would decrease MPS’ three-year enrollment average from 84,011 to 69,641.

- MPS’ five-year health benefit costs and retiree health benefit cost trends hold steady for 10 years. This would increase total annual health benefit costs from $203 million to $360.5 million and total annual retiree health benefit costs from $64.6 million to $173 million over the next 10 years.

- Total MPS annual pensions cost continue their gradual uptick from $70.1 million in 2012 to $73.5 million in 2022.

— M.F.