By now, the political lore is familiar: A major political party, cast aside by Wisconsin voters due to a lengthy recession, comes roaring back, winning a number of major state offices.

The 43-year-old new governor, carrying out a mandate he believes the voters have granted him, boldly begins restructuring the state’s tax system. His reform package contains a major change in the way state and local governments bargain with their employees, leading to charges that the governor is paying back his campaign contributors.

Only the year wasn’t 2011 — it was 1959, and Gov. Gaylord Nelson had just resurrected the Democratic Party of Wisconsin. Certain of his path, Nelson embarked on an ambitious agenda that included introduction of a withholding tax, which brought hundreds of protesters to the Capitol. Nelson also signed the nation’s first public-sector collective bargaining law — the same law that 52 years later Gov. Scott Walker targeted for fundamental revision.

Two different governors, two different parties, and two different positions.

Ironically, their assertive gubernatorial actions may produce the same disruptive outcome. By empowering the unions, Nelson’s legislation led to public-sector strikes and work stoppages. By disempowering the unions, Walker’s actions might lead to public-sector strikes and work stoppages.

In Walker’s case, union members reluctantly agreed to his pension and health-care demands, but have fought desperately to preserve their leverage in negotiating contracts. That raises the basic question of the Madison showdown: Why is Scott Walker so afraid of collective bargaining?

The answer can be found in the rise of the state’s teachers unions.

After the 1959 Municipal Employees Relations law passed, the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association became, in 1964, the state’s first certified teachers’ bargaining agent. Slowly, more teacher groups across the state began to organize in their districts. And in 1969, Ashwaubenon teachers became the first Wisconsin educators to hit the bricks and strike, as 83 teachers walked out for four days.

Part and parcel with these developments, a venerable professional group founded in 1853, the Wisconsin Education Association, transformed itself into a tough-talking trade union in 1972 called the Wisconsin Education Association Council, with the authority to bargain on behalf of teachers all over the state.

WEAC began collecting funds from its members ($3 apiece) to spend on supporting political candidates. According to the union, 88% of its endorsed candidates won in the 1974 elections. The union had arrived on center stage as a major player in Wisconsin politics.

Unionized teachers routinely flexed their muscle. Between 1969 and 1974, there were 50 teacher strikes in Wisconsin, despite a state law declaring public employee strikes illegal.Because there were no penalties outlined in the law, WEAC’s leadership frequently convinced its members to walk out anyway.

A turning point came in March 1974, when a bitter teachers’ strike in the small town of Hortonville prompted a resolute school board to fire and replace 88 striking teachers. All hell broke loose.

The strike, one of the longest in the history of American education, garnered national media attention and was litigated all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the justices affirmed the school board’s right to fire the strikers.

Asked later if it was wise for WEAC to pick a fight in conservative Outagamie County, its former executive director Morris Andrews said: “I would have chosen a better place.”

Determined to use the Hortonville defeat as a rallying cry for solidarity, Andrews began pushing for a stronger, more galvanized teachers union. Under his leadership, WEAC hired collective-bargaining and arbitration experts and implemented “pattern bargaining” strategies. The idea was to extract as much salary and benefit increases as possible from teacher-sympathetic school boards, then use that data to pressure more stubborn boards to cough up better pay and benefits.

Notably, WEAC’s post-Hortonville muscle led to passage of a 1977 mediation-arbitration law that guarantees settlement of deadlocked collective-bargaining disputes.

The new law essentially ended public employee strikes. According to the Wisconsin Employment Relations Commission, the state has had 111 municipal employee strikes since 1970; 90% took place prior to the 1977 med-arb law. Since 1982, there has only been one strike, in 1997 by Madison Metropolitan School District teachers.

The end of strikes, however, didn’t mean teachers were any less aggressive in negotiating. Aided by the new law, teachers redoubled their efforts to improve compensation. And they succeeded, judging by the costs of total pay and benefit packages.

For instance, statewide average teacher salaries increased 6% per year in the 16 years before the Hortonville strike. In the 16 years after the strike, the increase is pegged at 7% annually. Not a big difference, for sure.

But salaries are only a part of the picture. Consider that in the 16 years prior to Hortonville, average state per-pupil spending increased 6.7% per year. Post-strike, it jumped to 9.6% per year in the 16 years following the Hortonville clash.

Through collective bargaining, WEAC obtained concessions from management that appeared to have little fiscal effect, but in the long run greatly benefited its members.

It was in the early 1970s, for example, that local government employees across the state started to see taxpayers picking up the full cost of pension benefits — the very practice Gov. Walker fought against in his budget-repair bill.

In the ’70s, union leaders were figuring out the value of benefits; many of labor’s decision-makers were older and needed health and pension benefits more than the rank and file. They recognized that benefits were often not taxed, meaning that teachers usually got more bang from a buck in benefits than from a buck in pay.

Other provisions benefiting unions followed. In 1973, Wisconsin enacted the “Educational Standards Bill,” establishing that all teachers must be certified by the state Department of Public Instruction, that every school district must provide kindergarten, special education, guidance counselors, and other measures.

Also in 1973, Milwaukee teachers negotiated a benefit that paid their health care premiums when they retired — in 2016, this benefit will be worth $4.9 billion, or more than four times the size of the Milwaukee district’s current budget.

Teachers represented by WEAC often demanded that their health premiums be provided by WEA Trust — their own health insurer — at a cost often greater than insurance on the private market. (Started in 1970, WEA Trust is now the fifth-largest health insurer in Wisconsin.)

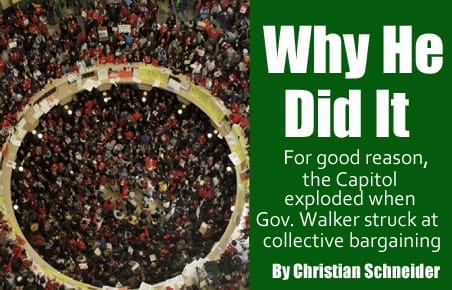

In none of these cases of advancing teachers and their union were the long-term fiscal costs known. While Capitol protesters in February offered to give up some short-term financial considerations, it is this slow, steady, tectonic shift towards enriching and empowering public employees that Walker sought to decisively reverse.

Bottom line: Even in giving up ground on a few major points, the negotiating tide on work rules and other matters still favors government labor.

Today, K-12 education funding dwarfs the next-highest state spending program by a measure of 4-to-1. In 2011, Wisconsin spent $5.3 billion on public school aids, compared to $1.3 billion on Medical Assistance.

Give WEAC credit for having the most aggressive and most sophisticated bargainers. Give it credit for executing a long-term strategy to enrich its members. But the union has been so successful for so long that it has sown the seeds for a humbling comeuppance.

It was this seemingly inexorable march toward higher spending that Walker is trying to halt by disassembling an overly powerful and deeply entrenched union machine.

Upon taking office in 1959, Gov. Nelson called on politicians to “think and act anew.” And that’s exactly what Gov. Walker is doing.

Christian Schneider is a senior fellow at the Wisconsin Policy Research Institute.