Vol. 23, No. 1

Executive Summary

Wisconsin state government did not solve its budget problem. As this report shows, Wisconsin’s next governor will enter office facing a $2.2 billion shortfall. Since there are no prospects for additional federal stimulus funding, this shortfall poses a more serious challenge than the one facing the governor and the Legislature last budget. The estimated $2.2 billion shortfall is based on an estimate of normal revenue growth (3.2% per year) and “normal” spending increases for a handful of state programs. Thousands of spending programs would see zero growth.

The severe recession that started in 2008 made the process of passing Wisconsin’s 2009-11 state budget painful and difficult. Most people know that the state addressed its well-publicized potential general fund budget deficit by increasing taxes and fees, slowing spending increases in some areas and reducing spending in others, and taking other steps such as transferring money to the general fund from other funds.

What many people don’t realize is that the biggest single contribution toward solving the state’s budget problems came from a massive infusion of federal stimulus funds. One-time federal funds available to the state through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided $2.2 billion in funding for programs such as Medical Assistance and school aids, which are traditionally funded with state general purpose revenues. This was actually a bigger factor in balancing the 2009-11 state general fund budget than the $1.1 billion in tax and fee increases or any other single measure.

Many people are probably hoping that things will return to normal in the next state budget cycle. But things won’t be easier the next time around, even if the economy steadily recovers from the recession, in part because the large amounts of federal money used to balance the 2009-11 state budget aren’t likely to be available when the next state budget is put together.

The outlook for Wisconsin’s next biennial budget in 2011-13 is sobering. A comparison of plausible revenue and spending projections shows that if state tax revenues grow at a long-term average rate of 3.2% per year, if spending increases at customary rates in just four basic areas where spending has almost always been increased (K-12 school funding, the Medical Assistance program, the University of Wisconsin System and the corrections system), and if spending is frozen for all other programs, the state will face a gap of $2.2 billion between its revenues and its expenditures in the next budget cycle.

It won’t be easy to close this gap. Even if the economy booms and produces robust revenue growth of 5.6% per year, which would match the peak of the last post-recession period, there wouldn’t be enough revenue. Even if all state spending is frozen, including an unprecedented freeze on spending for the basic programs that have received increases even in the toughest budget situations in the past, it wouldn’t completely close the gap. Tax increases on the wealthy would not come anywhere close to closing the gap. Major cuts to the operating budgets of all state agencies would not be enough to close the gap

This realistic estimate is particularly disconcerting since it demonstrates the difficulty of the task that will face the new governor. That person will discover that the problem cannot be solved by revenue growth, even if the economy realizes robust growth. It cannot be solved by freezing state spending. Finally, the problem is far too severe to be solved by increasing taxes on the wealthy or by cutting the bureaucracy. In other words, nothing that resembles business-as-usual will close Wisconsin’s looming budget hole.

Introduction

Recession and Aftermath: The Five-Year View

The severe recession that started in 2008 hit state budgets hard, in Wisconsin and across the nation. For Wisconsin policymakers, the process of passing the 2009-11 state budget was as painful and difficult as any in recent memory. Those involved in the process are probably hoping that things will return to normal in the next budget cycle. But the sobering reality is this: Things won’t be easier the next time around, and it’s not too early to start thinking about the issues that will have to be faced in the 2011-13 budget.

In many ways, Wisconsin and most other states balanced their budgets in the 2009-11 budget cycle as they had in past recessions by raising new revenues (both permanent and one-time revenues) and slowing spending increases. However, there was one unique feature in this budget cycle: the availability of extraordinary revenues from federal stimulus funds to help close the revenue-expenditure gap created by the recession.

The large amounts of federal money being used to balance state budgets now aren’t likely to be available two years from now. For that reason and others, even if there’s a steady economic recovery, the aftermath of the recession will continue to have a major effect on state budgets well into the next budget cycle, running from mid-2011 through mid-2013. The impact of the recession will be felt over at least a five-year period, from mid-2008 through mid-2013, not just for one or two years.

Everybody hopes that there won’t be more bad economic news or further revenue shortfalls in the next few years and that we’ll have a strong recovery. However, budgeting will still be extremely difficult in the next state budget cycle, no matter how robust the recovery is. In previous recessions, it could be expected that once a recovery arrived, state revenues would naturally pick up and budgeting would return to normal. This time it’s different. People need to recognize that and plan accordingly.

2008 Recession Slams State Budgets: In Wisconsin and Across the Nation

The severe recession, which hit with full force in the middle of 2008, wreaked havoc on state budgets across the nation by severely depressing revenues and generating demand for more government services. In Wisconsin, the Department of Administration (DOA) outlined the scope of the state’s budget problems in November 2008, when it reviewed the budget status for fiscal year 2008-09 (FY09) and then compared projected general fund revenues with state agency budget requests and spending commitments for the two-year budget cycle running from mid-2009 through mid-2011, covering fiscal years 2009-10 (FY10) and 2010-11 (FY11).

DOA reported on November 20, 2008 that Wisconsin faced a projected deficit in its previously enacted budget for FY09 and said that the state’s projected general fund ending balance at the end of FY11, assuming all the budget requests made by state agencies were granted, would be a negative $5.4 billion. To put that figure in perspective, agency budget requests for new general fund spending constituted $2.8 billion of the $5.4 billion total projected general fund deficit.1 (The state’s general fund is the largest part of the state budget and is funded with collections from the personal income tax, sales tax, corporate income tax and other taxes, as well as other state revenue sources available for general purposes rather than specified purposes.)

Things got even worse in Wisconsin in 2009 as the recession turned out to be deeper than initially expected. Revised revenue projections from the Legislative Fiscal Bureau (LFB) said that projected general fund revenues for the period covering FY09, FY10 and FY11 would be lower by a total of $1.9 billion compared with earlier projections.2 The overall fiscal problem the governor and Legislature had to deal with in 2009 was the largest on record in absolute terms.

Wisconsin obviously was not alone in dealing with budget deficits. The National Association of State Budget Officers and the National Governors Association, in their June 2009 Fiscal Survey of the States, reported that 42 states had to take steps to reduce budget gaps for FY09.3 The vast majority also had to cope with projected budget deficits for the 2009-11 budget cycle. Many states are not out of the woods yet; over half of the states have already said that they need to revise the budgets they adopted for FY10 as new revenue estimates have been made.4

So far, the revenue estimates on which the budget bill that was finally adopted in Wisconsin was based have been on target. Actual state tax collections for FY09 were almost the same as the Legislative Fiscal Bureau’s May 2009 revenue estimates, a remarkably good showing.5 However, in light of the revenue shortfalls other states are experiencing, Wisconsin’s revenue collections will have to be closely monitored for the next two years.

Dealing With the State Budget Deficit in 2009

(With Help from Federal Stimulus Funds)

In similar recessionary situations in the past, states dealt with projected general fund deficits by increasing taxes and fees, denying many agency requests for increased spending, and reducing existing spending in some areas. Other commonly used steps have been to tap money in rainy-day funds, transfer money to the general fund from other separate funds, support more spending with bonding, and postpone expenditures to future years.

In this budget cycle, one other option fortuitously became available: use of substantial amounts of emergency federal funds for general fund purposes. In early 2009, the president and Congress enacted the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), making $250 billion available to all the states. Most of this money was made available in state fiscal years FY09, FY10 and FY11, and about $130 billion of it nationwide was available for flexible fiscal relief, which could be used to offset projected state general fund budget deficits.

Wisconsin relied heavily on the use of the federal stimulus funds to address its projected budget deficit. A budget adjustment bill (sometimes referred to as the state stimulus package) that passed in February 2009 and another bill that passed in early June used federal stimulus revenues to avoid a deficit in FY09. The regular biennial state budget bill signed into law by the governor June 29 relied heavily on federal stimulus revenues to help balance the budget in FY10 and FY11.

In the end, a very substantial part of Wisconsin’s projected general fund budget gap was addressed with the use of federal funds. The total amount of federal funding available to Wisconsin over a period of three fiscal years under ARRA is over $3.4 billion, of which over $2.2 billion is being used to offset spending that would otherwise be paid for with general purpose revenues (GPR), or an average of approximately $740 million per year.6

| Wisconsin Fiscal Years | Total Stimulus Funds Available | Total for GPR Offset |

| FY 09, FY10, and FY 11 | $3.452 billion | $2.223 billion |

The federal stimulus funds are being used to offset general purpose revenues in several major areas:

| Medical Assistance/SeniorCare | $1,270 million |

| General school aids | $789 million |

| Shared revenue for local governments | $76 million |

| Social service programs | $74 million |

| Corrections-related programs | $13 million |

Wisconsin’s experience is typical. The Rockefeller Institute of Government in Albany, N.Y., has reported that across the country states addressed a substantial part of their budget gaps with the use of federal stimulus funds.7

In addition to federal funds, Wisconsin used a range of other tactics to address the projected state deficit. On the revenue side, actions included raising revenues with increases in selected taxes and fees, as well as transfers of money to the general fund from other funds. In total, the amount generated for the general fund in FY10 and FY11 from increases in general fund taxes and fees was $1.153 billion, and the amount generated from transfers from other funds totaled $240 million.8 (See Chart 1.)

Chart 1

On the spending side, actions included denying many agency requests for new spending (the budget bill initially introduced by the governor denied $1.760 billion of requests for new spending that had contributed to the initial calculation of the projected deficit) and reducing existing spending levels in some areas (in part by reducing spending for state agency operations, through employee furloughs and other measures).9 Other actions included deferring some expenditures to future fiscal years.

As these figures show, the biggest single contribution toward solving Wisconsin’s deficit problem came from one-time federal funds ($2.2 billion), followed by tax and fee increases, with transfers from other funds playing a smaller role.

Outlook for the Next Budget

(Without Help from Federal Stimulus Funds)

Ongoing Revenues Compared With Ongoing Spending Commitments

It’s tempting to think that state budgeting will return to normal after the recession ends and the difficult 2009-11 budget is behind us. In the past, recessions have often had short-term impacts, and states have returned to normal patterns of budgeting after a couple of years of crisis management.

However, this time things look different. It is hard to envision a scenario in which the next budget cycle will be anything like normal. Even under optimistic assumptions, Wisconsin faces difficult problems, which won’t be solved simply through economic growth, small adjustments to reduce the costs of operating state agencies or selective targeted tax increases.

Predicting what’s going to happen in the budget cycle two years down the road is tricky even in normal economic times and becomes exceptionally difficult at a time of unprecedented economic volatility. However, it’s important for citizens and policymakers to understand the broad parameters of the state’s fiscal outlook as they plan for the future.

We can begin to get a rough idea of the shape of the next budget by looking at projections for ongoing revenues and expenditures. Any revenue sources that are ongoing (taxes and fees) will be available to support continuing ongoing spending. Revenue sources that aren’t ongoing, such as the limited-time federal stimulus revenues, won’t be available to support ongoing spending.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau addressed this subject in a memo about Wisconsin’s 2011-13 budget outlook issued July 7, 2009. It reported that under the 2009 budget bill as signed by the governor, the state’s ongoing base level of spending in fiscal year 2011-12 (FY12) would exceed available ongoing base revenues by $899 million, and ongoing expenditures in fiscal year 2012-13 (FY13) would exceed available ongoing revenues by $1.150 billion, for a total cumulative two-year gap of $2.049 billion.10

If federal revenues were available at the same average level as in the previous three fiscal years, the gap would be about $740 million less in each year, or $1.480 billion less in total. When compared with previous budget cycles, the gap identified by the LFB is substantial. Without the federal stimulus funds to help close the gap, addressing it will be much more difficult.

It appears highly unlikely that the federal government will make special stimulus revenues available to states two years from now. The unprecedented $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act package passed in early 2009 was billed as a one-time stimulus package needed to deal with an unexpected and unprecedented national economic crisis. Since it passed, federal deficit projections have soared. The deficit for the 2009 federal fiscal year that ended Sept. 30 was $1.4 trillion, $1 trillion more than the previous year and a post-World War II record 10% of gross domestic product.11 Concerns about the long-term dangers of record federal debt levels have increased. Given the heightened concerns about the federal deficit, the political outlook for another stimulus package is very negative.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau’s projections for FY12 and FY13 were based on several assumptions:

- It was assumed that spending would not increase above the base-year level in most areas, including school aids, Medical Assistance, shared revenues and higher education, because the Legislature has to pass specific legislation to authorize increases in most areas. The only spending increases that were factored in were those to which the state is already legally committed.

- No assumptions were made about tax revenue increases based on economic growth. It was assumed that tax revenues would not increase, except in those areas in which increases are already scheduled to take place under existing law.

- It was assumed that base-level expenditures funded with one-time revenues from federal funds would have to be funded with general purpose revenues, and that one-time revenues from sources such as transfers from other funds would not be available again.

- It was assumed that a positive balance of $275 million would be carried over from FY11 to FY12.

Outlook for the Next Budget: Scenarios Assuming Revenue and Spending Changes

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau analysis assumed that, for the most part, there would not be any increases in revenues or spending in the next budget above ongoing base levels. How would the next budget look if we made some assumptions about likely revenue growth and about the magnitude of the spending increases that would be most likely to be considered by the Legislature?

We can go the next step beyond comparing ongoing base revenues with ongoing base spending and get a good picture of the future state fiscal outlook by comparing plausible projected increases in revenues with customary, basic increases in spending. On the spending side, this “projected growth” approach will just look at the basic spending increases that policymakers are most likely to want to support, not at all the spending requests made by agencies. These are the areas in which increases have almost always been approved because pressures for increases make them difficult to avoid, even in very tight budgets, for both policy and political reasons.

This approach arguably gives the most realistic picture of the gap between expectations and available revenues that the state will face in the next budget. It assumes that there will be average revenue growth, that most agency requests won’t be granted when the budget is tight, and that there will always be strong interest in granting budget increases in several basic areas.

The difference between the likely available revenues and very basic spending increases will give us the starting point for thinking about the magnitude of the likely revenue-expenditure gap and for assessing how difficult it will be to close the gap using various alternative approaches.

On the revenue side, the rate at which tax revenues will increase in the next biennium is obviously very hard to predict, especially during this period of extreme economic uncertainty. Neither the Legislative Fiscal Bureau nor the Department of Revenue has made long-term tax revenue projections beyond the end of FY11. The LFB’s May 11, 2009 revenue projections, on which the Legislature’s final budget action was based, assumed that tax revenues would drop by 7.1% in FY09, followed by another drop of 3.3% in FY10 and then an increase of 4.5% in FY11, all based on the law prior to any tax law changes adopted in the budget bill. The national economic forecast by Global Insight on which these revenue projections were

based assumed that nominal GDP would drop by 1.7% in calendar year 2009, followed by growth of 2.3% in 2010 and 4.7% in 2011, which looks like a forecast of a “U”-shaped recovery pattern.12

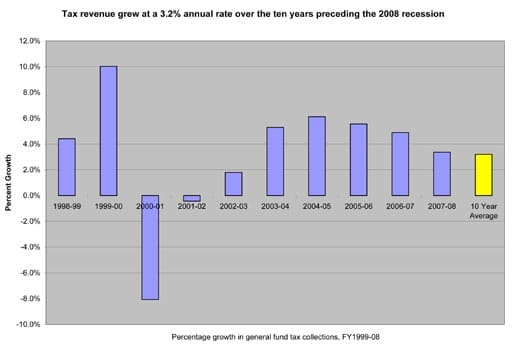

Chart 2

For purposes of this exercise, it will be assumed that there will be normal revenue growth for the 2011-13 budget cycle, with tax revenue growing at a rate of 3.2% per year in FY12 and FY13. This was the average growth rate for general fund tax revenues over the 10-year period from fiscal years 1997-98 (FY98) through 2007-08 (FY08), a period encompassing a variety of economic conditions.13 (See Chart 2, “Tax revenue growth averaged 3.2% over a 10-year period.)

If tax revenues grew at a 3.2% rate, available general fund revenues would be $14.026 billion in FY12 (including the available carryover balance from FY11) and $14.220 billion in FY13.

Then, it will be assumed that the state will only consider spending growth in a handful of basic programs, meaning that spending would increase at usual rates in the areas in which spending has historically been increased in almost every budget, while remaining flat in other areas. Under this scenario, spending is assumed to increase at long-term historical growth rates in four major program areas, all of which are areas where annual spending increases have almost always been adopted because of increasing numbers of people to serve, rising costs and strong public demand for increases.

The “Big Four” programs are school aids (including school-related tax credits), Medical Assistance, the University of Wisconsin System, and corrections programs. Over the past 10 years, annual general fund spending on these programs has grown at annual rates of 3.7% (school aids), 7.9% (Medical Assistance), 2.6% (the UW System), and 6.2% (corrections programs).14

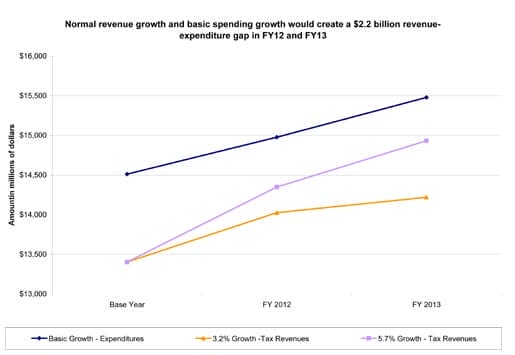

Basic spending growth in just the four major spending areas that have historically grown in almost every budget would result in general fund spending of $14.977 billion in FY12 and $15.480 billion in FY13.

The bottom line is this: If we had a 2011-13 state general fund budget with normal revenue growth and basic spending growth, the cumulative budget gap at the end of FY13 would be $2.211 billion. On a year by year basis, the gap would be $951 million in FY12 and $1.260 billion in FY13. (See Chart 3.)

Chart 3

Obviously, this scenario involves very general estimates and very broad projections, but this is a plausible illustration of the situation the state could face in the next budget cycle. The revenue and spending assumptions that underlie this scenario could be varied, but under any set of plausible assumptions the same basic conclusion would be reached: The budget gap will be daunting.

This projected budget gap of $2.2 billion is less than the $5.4 billion projected gap identified by DOA prior to the 2009-11 budget cycle. However, it should be kept in mind that this scenario only factors in pressures for increases in funding in four basic spending areas, and does not include agency budget requests for spending in all other areas that were included in DOA’s calculations of the 2009-11 projected budget deficit. Hence, while the outlook for 2011-13 may not appear quite as dire as it was entering the 2009-11 budget cycle, it certainly ranks high among the most challenging the state has ever faced.

It should also be noted that this scenario assumes that all of the assumptions on which the FY10 and FY11 budget is based are accurate. This means that in the next two years, tax revenues won’t fall short of projections, spending on entitlement programs won’t exceed projections, all of the planned reductions in state operations spending will yield the projected savings, all of the budgeted transfers of money to the general fund from other funds will take place as planned, and no other unpleasant surprises will occur.

Solving the Budget Gap in the Next Budget

How difficult will it be to address this looming $2.2 billion gap? Simply put, there aren’t any easy solutions. The first thought that many people have is to hope for a robust economic recovery. But even if we have very strong economic growth, it won’t completely close the gap.

We could, for instance, assume that tax revenues would grow at a relatively high rate of 5.7% per year in FY12 and FY13, the average growth rate in fiscal years 2003-04 (FY04) and 2004-05 (FY05), when the state was emerging from the most recent recession before this one.15 That would result in available general fund revenues of $14.349 billion in FY12 (including the available carryover balance from FY11) and $14.933 billion in FY13. Even with this assumption, the budget gap would still be $1.175 billion if we funded basic spending growth.

The next thing people think of is holding spending increases below the basic level of increases or even imposing an unprecedented freeze on all state spending. But even if spending for all state programs was absolutely frozen for two years and we had normal revenue growth, the budget gap would still be $778 million.

What about targeted tax increases, such as tax increases on the wealthy? In the last budget, the income tax increase on high earners generated $287 million over two years, far from enough to close the $2.2 billion gap.16

How about cuts to the state bureaucracy? The fact of the matter is that the majority of state spending is devoted to aids to schools and local governments and to benefit payments for individuals; only 27% of the state’s general fund budget is used for the costs of operating state agencies.17 A 5% cut to all spending for the actual operating costs of state agencies, including the UW System and the Department of Corrections, would reduce spending by about $375 million, not nearly enough to close the gap.

There is one very optimistic scenario that produces a balanced budget by the end of the biennium: If we assume that there will be very robust economic growth and an absolute freeze on all state spending for two years in a row (and no unpleasant surprises), the state would still have a deficit of $163 million in FY12, but would see a relatively slim positive ending balance of $258 million by the end of the biennium. Obviously, this scenario would require a lot of good luck, coupled with some difficult decisions.

In short, there aren’t any easy solutions to our looming budget dilemma. Putting all of this together, several key points emerge:

- First, the budget gap facing the state in the 2011-13 budget cycle won’t be solved with economic growth alone, because the gap will be significant even if it is assumed that there will be very strong economic and revenue growth along with even minimal spending increases.

- Second, the gap can’t be easily solved with a spending freeze and cuts to agency operations budgets alone.

- Third, the gap can’t be solved simply by increasing taxes on high earners or other selected groups.

It is unlikely that a major source of new revenue such as the federal stimulus funds or the tobacco securitization revenues that were used to address the budget gap in the 2001-03 budget cycle will materialize. Moreover, many of the other tactics used to solve the budget gap in the past few years, such as large transfers of money from other funds to the general fund, have probably reached their limits.

That leads to a final key point:

- Solving the state’s budget gap in the next cycle will require a fundamental evaluation of how much the people of Wisconsin can afford to spend for government services, and a thorough review of the state’s system of financing and delivering those services.

Wisconsin is not alone in this problematic budget situation. The Rockefeller Institute has looked at a range of estimates for expected revenue growth for states nationwide and has concluded that, under both high and low projections for revenue growth, states will face significant budget gaps in FY12 and FY13, ranging from 4% to 7% of spending. It also expects that minimal amounts of federal stimulus funding will be available to address these gaps.18

Almost every state will face the same difficult budget situation Wisconsin faces in the 2011-13 budget cycle to a greater or lesser degree. Most states will have to thoroughly reevaluate the structures of their budgets. The states that do the best job of understanding and planning for the difficult decisions that must be made will be best prepared to deal with the stresses of the next budget cycle.

Conclusion: Planning for the Next Budget Won’t be Business as Usual

Balancing Wisconsin’s budget in the next cycle will be extremely challenging, even if there is a robust economic recovery. In the 2009-11 cycle, federal funds closed a significant part of the budget gap the state faced, and other revenue increases and spending changes closed the rest of the gap. In the 2011-13 cycle, the budget gap will be significant, even if the economy is performing very well, and it is not likely that another round of federal stimulus funds will be available.

Some people may assume that the recession-induced crisis in the state’s finances will soon pass and it will be business as usual in the future. That’s not correct. This is an alert that state budgeting will not readily return to normal after the recession ends. The federal stimulus funds provided some breathing room and helped the state get through a very difficult budget cycle. When they’re gone, fundamental budget changes will have to be made in the 2011-13 budget cycle.

The reality is that in the next budget cycle the state will face a situation in which the basic spending trend line will be well above the revenue trend line. That means that state citizens and policymakers need to discuss fundamental changes to the state’s revenue and spending patterns that will put Wisconsin on a sustainable fiscal course for the future.

Endnotes

1Wisconsin Department of Administration, Division of Executive Budget and Finance, “Agency Budget Requests and Revenue Estimates, FY2010, FY2011,” November 20, 2008.

2Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau letters to Joint Committee on Finance Co-Chairs re general fund revenue estimates, January 29 and May 11, 2009.

3National Association of State Budget Officers and National Governors Association, “The Fiscal Survey of States,” June 2009.

4“State Budget Gaps Linger at Year’s End,”

Stateline.org, The Pew Center on the States, December 21, 2009.

5Legislative Fiscal Bureau memo, “Preliminary 2008-09 General Fund Tax Collections,” September 1, 2009.

6Legislative Fiscal Bureau memo, “Federal Stimulus Funds,” July 7, 2009.

7Rockefeller Institute of Government, “What Will Happen to State Budgets When the Money Runs Out?,” February 19, 2009.

8Legislative Fiscal Bureau memos, “State Tax and Fee Modifications Included in 2009 Act 28,” July 8, 2009, and “Use of Certain Funds within the State’s Budget,” July 15, 2009.

9Department of Administration, Division of Executive Budget and Finance, “Budget in Brief,” February 2009.

10Legislative Fiscal Bureau memo, “2009-11 and 2011-13 General Fund Budget Under 2009 Act 28,” July 7, 2009.

11“$1.4 Trillion Deficit Complicates Stimulus Plans,” The New York Times, October 17, 2009.

12Legislative Fiscal Bureau letter to Joint Committee on Finance Co-Chairs re general fund revenue estimates, May 11, 2009.

13Legislative Fiscal Bureau Informational Paper 1, “General Fund Tax Collections,” January 2009.

14Department of Administration Annual Fiscal Report, 1999; Legislative Fiscal Bureau Budget Paper Number 700, “County and Municipal Aid Payments,” May 5, 2009; Legislative Fiscal Bureau, “Comparative Summary of Budget Recommendations,” June 2009.

15Legislative Fiscal Bureau Informational Paper 1, “General Fund Tax Collections,” January 2009.

16Legislative Fiscal Bureau, “Comparative Summary of Budget Recommendations (2009 Act 28),” August 2009.

17Legislative Fiscal Bureau, “Comparative Summary of Budget Recommendations (2009 Act 28),” August 2009.

18Rockefeller Institute of Government, “Fiscal Stimulus and State and Local Governments,” May 12, 2009.