James Madison would be dismayed by his namesake capital’s role in relinquishing local control to get federal grants

This is an excerpt from the Badger Institute’s recently published book, “Federal Grant$tanding: How federal grants are depriving us of our money, liberty and trust in government — and what we can do about it.”

James Madison had barely been buried in 1836 when territorial leaders named the place that would become the capital of Wisconsin after him. But one need only look at the local street signs to know it was more than just the common custom of naming places posthumously after deceased presidents that prompted the choice.

Were the “Father of the Constitution” to rise from his Virginia grave and today walk the streets of the Wisconsin city that honored him, he would recognize the names of virtually all of the main avenues and roads.

Dozens of them around the Capitol building — including Hamilton and Washington, Langdon and Mifflin, Morris and Pinckney and Wilson and Carroll and King — were named after the men who attended the Constitutional Convention alongside Madison in 1787.

Madison the man would immediately realize that Madison the city, at least around the Capitol, is quite literally an everlasting commemoration of the U.S. Constitution and most of the 39 men who signed it in Philadelphia.

Were he, on the other hand, to walk inside the state Capitol at the center of it all, witness the workings of the budget, see how policy is made and why, ascertain just how deeply the state government has become intertwined with and dependent on the federal government, he might feel less than honored.

The Capitol at the heart of Madison the city, after all, contravenes so much of what Madison the man — and the rest of the framers of the Constitution — believed about the delineation of state and national governments.

National vs. state governments

Had Madison lived to witness the naming of this city so far from the seat of national power, it’s likely he initially would have taken considerable comfort from the fact that settlers out here in the hinterlands chose to commemorate the Constitution at all.

One of the principal concerns of those who opposed ratification, after all, was that it would be a threat to the states, which were supposed to be the repositories of primary political power. Without the states protecting individual liberties and assuring that the power to govern in our republic comes directly from the people, detractors feared, the distant and intrusive national government would extend its tentacles into all facets of life.

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were both nationalists to be sure, at least in the context of the times. They, after all, were the authors of a Constitution forged in reaction to what Jay Cost calls “the miserable experiences of the 1780s — an impotent national Congress combined with selfish and often illiberal states.” America was doomed under the mere Articles of Confederation. Hamilton was explicit in Federalist 6 about the dangers of “independent, unconnected sovereignties” that he thought might devolve into violent conflict.

Fearing unconnected sovereignties, however, should not be confused with fearing a balance between national and state power. Madison in particular was careful to build in extensive safeguards for the states. Writing as Publius in the Federalist Papers, he countered fears of national overreach with unmitigated assurances that the states would have powers later codified in the 10th Amendment.

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people,” famously reads that part of the Bill of Rights.

The Federalist Papers were not diaries; they were public arguments, the equivalent of 18th century op-eds that appeared first in the newspapers of New York. They were not a venue for expressions of doubt or rumination. But the authors — Hamilton, Madison and at times John Jay — seemed utterly convinced that the purview of the states would remain separate and apart.

Hamilton, a firm believer in the “splendor of the national government,” doubted ambitious national politicians would even care enough about mundane matters of state and local interest to attempt to usurp their power.

He did recognize the “wantonness and lust of domination” inherent in many politicians. But even “allowing the utmost latitude to the love of power which any reasonable man can require, I confess I am at a loss to discover what temptation the persons intrusted with the administration of the general government could ever feel to divest the States of (their) authorities,” he wrote in Federalist 17.

The exercise would be “troublesome” and “nugatory” and “contribute nothing to the dignity, to the importance, or to the splendor of the national government,” he believed.

In any case, Hamilton assured readers in Federalist 17 that it would “always be far more easy for the State governments to encroach upon the national authorities” than vice versa.

Madison, much more the adherent of decentralized power, wholeheartedly agreed.

In Federalist 45, he wrote that state governments “will have the advantage” over the federal government “whether we compare them in respect to the immediate dependence of the one on the other; to the weight of personal influence which each side will possess; to the powers respectively vested in them; to the predilection and probable support of the people; to the disposition and faculty of resisting and frustrating the measures of each other.”

“The State governments may be regarded as constituent and essential parts of the federal government; whilst the latter is nowise essential to the operation or organization of the former,” Madison continued.

“Federal Grant$tanding” reaffirms the wisdom of the founding fathers’ federalist vision. Government is more responsive, accountable, efficient and variegated in a way that accommodates all the diversity of America and all our individual foibles, ambitions and proclivities when it is closer to the people.

The book also illustrates, unfortunately, in one concrete and essential way — the federal grants-in-aid system — how that vision has failed to endure and what the very real consequences of that failure are.

Grants-in-aid

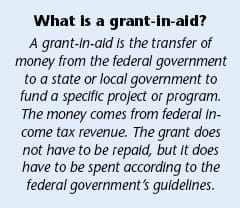

There are many types of direct federal spending and assistance to individuals and programs throughout the United States, including contracts, direct entitlements and a wide variety of grants. “Federal Grant$tanding” focuses exclusively on one type of spending: grants-in-aid — grants that flow directly from federal coffers to state and local governments.

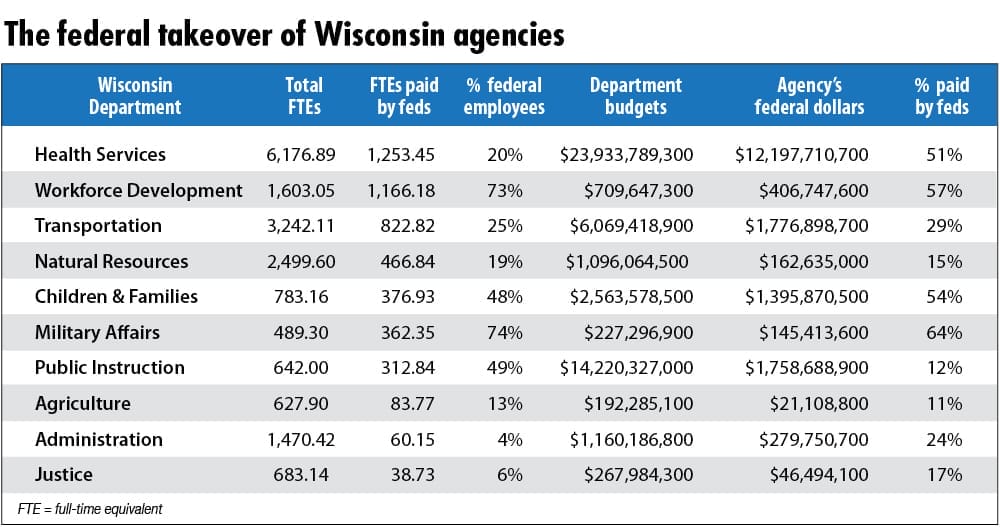

Such grants sent from Washington have risen from just $7 billion in 1960 to an estimated $728 billion in 2018. The system has grown so quickly and so large that most states today get about one-third of their revenues from the federal government.

Overspending is one concern. The Congressional Budget Office now projects that federal debt held by the public will reach 96 percent of gross domestic product (or $29 trillion) by 2028 — the largest percentage since 1946.

There are obviously other categories of spending, though, that are much larger than grants-in-aid. So concern about debt constitutes only one of the reasons we focus on this particular type of federal spending.

We focus on monetary cost, to be sure. But the ever-expanding grants-in-aid system illustrates just how deeply dependent states, including Wisconsin, are on the federal government in other ways as well.

The book demonstrates how the federal government exercises an influence over the lives of Americans that is increasingly personal, and it details how the federal government effectively frustrates the desires and abilities — indeed, the independence and liberties — of so many state residents, no matter their political bent.

And for what reason?

Wisconsinites paid over $53 billion in taxes to the federal government in 2017 alone, according to the Internal Revenue Service Data Book. Some of that money stays in Washington, D.C., or is spent outside the country. And money that does flow back to the states does so in many ways: directly to people receiving federal entitlement payments such as Medicare, Social Security, unemployment compensation or food stamps; salaries and wages of federal employees paid directly by the federal government; federal purchases of services or goods such as military equipment (procurement); and grants.

There are, in turn, many types of grants, including grants to universities and grants to non-governmental organizations. But a big chunk of money takes the form of grants sent right back to state governments and local governments for everything from road building to educating our kids to child care to housing.

There are scores and scores of such grant programs and, as you’ll see, there are two more bureaucracies — one at the state level and another at the local government level — that also have been constructed to make sure the “federal” money arrives and is directed back to the same places that sent it to Washington in the first place.

Many politicians in Washington and elsewhere love these grants. Those in the capital get to claim they are helping constituents (i.e., voters) back home; and politicians back home get to brag about securing federal money to build the latest road or elevator or building.

Our goal is not to look at the issue from the perch that is Washington, D.C. Nor is this merely a theoretical or academic examination of constitutional issues. Quite the opposite. Using Madison the city as our platform, we write from the states’ view and with the knowledge that the frustration and discontent we’ve found in Wisconsin exist in the other states as well.

“Federal Grant$tanding” vividly illustrates from the state perspective just how far the country has strayed from the vision of the founding fathers. James Madison had an essential vision that the states would retain powers numerous, distinct and indefinite. The city named after him, ironically, fundamentally undermines that vision. But it goes much further than that.

It shows in concrete ways that federal dollars and influence are undermining local decisions, accountability and innovation, driving up costs for taxpayers, creating confusing and nonsensical bureaucratic overlap, transferring authority to unelected bureaucrats instead of elected officials who are accountable to the people, and fostering a culture of unrealistic and illogical expectations.

There has been much written over the years about constitutional issues that set parameters for grants to the states. That is a starting point, and a necessary framework. We indulge in some of that. It’s important to remember what the Federalists and Anti-Federalists both thought at the time the Constitution was debated and ratified. But our real goal is not to show why federalism mattered as a concept in 1789; it’s to show why it matters today, why true federalism will improve both our wallets and our lives.

We want to start to change the mindset in this country that federal money is “free.” And we have proposed straightforward solutions that can help restore both state control and the confidence of citizens in their governments. While we hope change can come from Washington, our goal is to foment discussion in and pushback from the states as well.

Right now, citizens’ trust and confidence in government — especially the federal government — is at a historical low point. Most Americans who live far from the nation’s capital no longer believe in our leaders or their ability to govern. Madison and Hamilton would be deeply concerned about the ramifications of that loss of faith for our representative democracy and likely surprised by their own lack of prescience.

We have only to look at their words and love of this country — and compare those words to the comments and attitudes of citizens in 2018 — to realize that.

► Read “Federal Grant$tanding”