In need of quiet solitude not long ago, I did the obvious: I got on Milwaukee’s streetcar, The Hop.

It did not disappoint: In all, five people Hopped on, then off, as we trundled 2.1 miles across downtown. It’s a bit under what the latest federal transit data says is average: In 2021, for every mile the trolley ran, four people got on; for every hour a 150-passenger car runs, 23 people board.

That’s why it surprised no one that, when a garbage truck crashed into a streetcar in March, no passengers were hurt, there being no passengers.

It’s why, again in those latest Federal Transit Administration numbers, The Hop cost $15.03 per ride in operating expenses, never mind the cost of rails and wires — not a dime of it paid by passengers. It’s why the Legislature is doing Milwaukee a favor when it says, “enough.”

The low passenger counts along the route that was supposed to be most hungry for trams — train station to Third Ward to office towers — are only half the equation. The numerator is the cost. The FTA’s latest figures say that in 2021 for every hour a Milwaukee streetcar is out impeding traffic, it costs the city $351.

Compare that to the alternative. The Milwaukee County Transit System runs not only throughout downtown but through much of metro Milwaukee. It uses buses, plain old buses, though clean and comfortable. Every hour one is running the streets, it picks up about half as many passengers as the streetcar, but it costs only $103 to operate, or 29% of the price.

Buses just cost less to run: $142 per vehicle-hour in Madison, for instance, or $95 in Appleton. Streetcars cost more: Portland’s larger, established system pays $251 an hour in operating costs. Philadelphia pays $275 an hour, says the FTA, while its buses cost $169 to do the same thing. This suggests The Hop will remain costly even if the city expands it past the best-case starter route, as supporters hope.

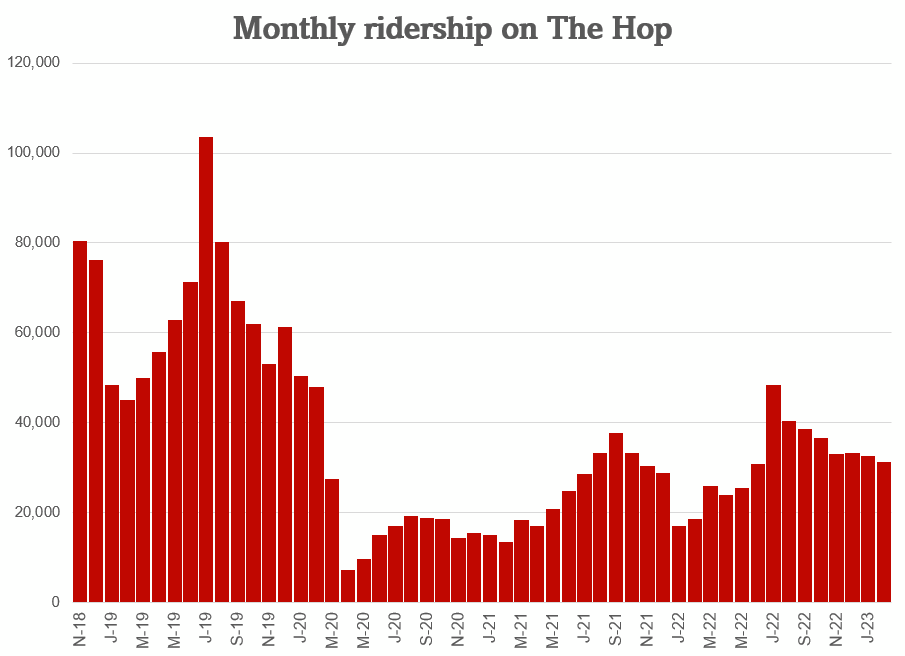

It will remain costly even if ridership bounces back. In 2019, when new, the trolley attracted 760,000 people to take fare-free rides. Ridership crashed in 2020 amid pandemic lockdowns. Despite The Hop still being fare-free — no fareboxes are even installed — it has only half-recovered, with 372,000 passengers last year. Squeeze your eyes shut and wish hard for 500,000 this year: That’s still about $10 a ride.

Again, that’s just operating costs. The existing 2.1-mile set-up cost about $124 million, including about $4.5 million each for the cars. The city in 2019 priced a 0.4-mile extension at $28 million, or about $70 million a mile, not out of line with what Seattle paid over a decade ago, for rails and wires that serve no other means of transport. Buses, by contrast, use existing pavement. And they cost about $900,000 each. That means you can afford to run more of them, more frequently, for better service.

But talk of dollars per ride misses the point of a project that’s less about transportation than transformation. The city’s website says, “The vision for The Hop has always been to serve as a catalyst for economic growth.” Ex-mayor Tom Barrett, talking up expansion, billed it as “a catalyst for economic growth.” The city’s grandiose new plan to rip up and rebuild downtown, touts “the ability of the streetcar system to spur economic development.”

It’s not about moving people around but signaling coolness. If developers see rails, goes the thinking, they’ll want to build.

The idea has been questioned or debunked for years, with development mostly coming from tax incentives. In Milwaukee, Barrett in 2019 tried claiming The Hop spurred millions in development. His story imploded when Badger Institute journalist Ken Wysocky interviewed the developers involved. Most said emollient things about the costly rolling adornment but said it didn’t catalyze their cranes.

Want to help downtown? How about doing a better job at curbing Milwaukee’s horror-show moments in the national headlines. Milwaukee’s crime spike has scarcely abated, and the city can’t fill even the depleted number of authorized police positions.

This is why the Legislature offered ample new funding specially to Milwaukee — not only a share of the state’s sales tax revenue but power for the city to levy the extra sales tax it long has sought. The city said it couldn’t afford both cops and its pension obligations, so the Legislature is offering money — so long as the city doesn’t spend any of it on its luxury-priced decorative trolley that cost $124 million before the first rider boarded and costs another $15 a ride now.

Both city officials and Gov. Tony Evers may complain, but this is what responsibility looks like.

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields