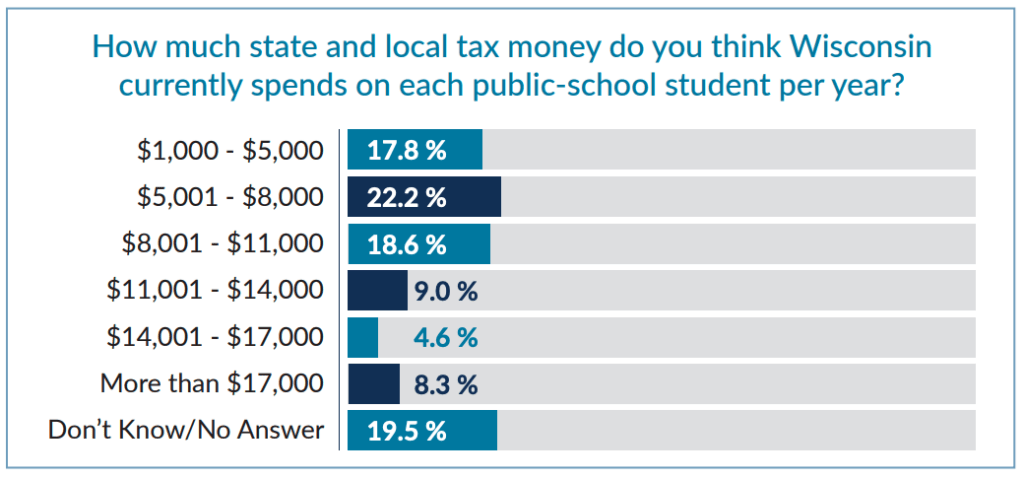

Seeing how often Wisconsinites have been told that public school districts are starving, it isn’t surprising that when asked to guess how much tax money districts spent per student, they whiffed.

And not by a little. The most common guess was about one-third to one-half of what the Department of Public Instruction says is the real figure.

In all, two in three of 700 people polled on behalf of the state’s chamber of commerce in early May guessed low. Less than 5% got it right. A fifth of respondents just shrugged.

This makes a difference when people think about the historic bump in funding for families using Wisconsin’s charter and school choice programs. The increase, which the Legislature passed as part of a deal with Gov. Tony Evers, is large enough to reduce a yawning gap between what is available for different groups of students — though it does not close it.

The correct answer for how much public school districts spend is $15,363 per child: That’s what the DPI calls the “total educational cost per member,” the statewide average of what districts spent on instruction, staff, administration, buses and buildings in 2021-22. In Milwaukee, the state’s largest district, it’s $18,035. In Madison, it’s $17,944. Ritzy suburbs? Mequon-Thiensville spent $16,682.

So when poll respondents guessed it was between $5,000 and $8,000 per child — their most common guess — they weren’t merely a little low. Pollsters then gave the correct figure and asked whether the funding following kids to charters or choice schools should rise, and Wisconsinites, being fair-minded, said yes by a 59%-33% margin.

For the record, when parents send a child to a private school under the choice program, right now, $8,399 of state funding follows to an elementary school, or $9,045 to a high school. The deal Republicans struck with Evers boosts it to about $9,500 for elementary schoolers and $12,000 for high schoolers. Charter schools, now funded at $9,264 per child, get boosted to $11,000 per child, putting them at the very bottom end of the range of what traditional district schools will spend.

In each case, when a mother decides that her son can’t take another year in the local district high school and looks at her options, she’ll still be moving him to where taxpayers will invest much less — going from $16,163, if she’s in Green Bay, down to $12,000. But that’s better than the school of her choice making do now on $9,045 and the kindness of donors. The boost ensures that she and other parents still will have an option.

For many independent schools, especially at the costlier high-school level, the increase is “the difference between keeping their doors open or having to end operations entirely,” as one Milwaukee educator told a newspaper.

So good deal, Republicans. Good job, Governor. After he made the deal, Evers came in for sniping from teachers unions, his customary allies, who weren’t satisfied with hundreds of dollars per pupil in increased funding that also went to district public schools. It smacked of envy, and Evers deserves credit for standing up to it.

And while Republicans long have been friendlier to choice, the bargain isn’t a matter of rewarding friends. In that poll, 74% of Wisconsin voters agreed that “parents, not the state, are responsible for determining the type of education that their children need.” The constituency for school choice’s underlying principle extends way past Republican voters.

The deal gives Wisconsinites what they, in the main, want. The Legislature is following parents.

Since 2014, even as enrollment in traditional district schools has fallen 7% — and fallen every single year — the number of children sent by parents to independent schools via the choice program has risen 76%. The total number of Wisconsin children in any kind of school has fallen by the thousands, year after year, but the number in choice schools has risen by thousands, year after year.

Critics often claim choice schools are “unaccountable.” They’re wrong: Private choice schools must report results publicly to regulators, must follow state laws accommodating children with special needs, must submit annually to fiscal audits by the DPI, a regulator so notoriously nitpicking that, as the Badger Institute’s Jim Bender noted, it rejected families’ applications for choice because the utility bills they used as proof of residency abbreviated their city’s name.

Choice schools are accountable, Bender told lawmakers this week, in the most relevant way: “Nobody would attend if a parent doesn’t choose that school.” That, he told an Assembly hearing, “is the ultimate form of accountability.”

That 76% increase in choice enrollment came before any funding boost. What the state puts into a child’s education is measured in dollars. What parents invest is an irreplaceable treasure — their daughter’s or son’s future, a child’s one shot at learning. If parents are putting that investment in a particular set of schools, it’s good that the Legislature and governor follow their lead.

Patrick McIlheran is the Director of Policy at the Badger Institute. Permission to reprint is granted as long as the author and Badger Institute are properly cited.

Submit a comment

"*" indicates required fields