The Milwaukee Housing Authority competes with private developers with its luxury apartment project downtown

Editor’s note: “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield, and government to gain ground,” Thomas Jefferson famously wrote in 1788. “As yet,” he added, “our spirits are free.” Some 231 years later, they might not be much longer if government leaders and bureaucrats continue trying to take over traditional private-sector enterprises like housing development, retirement planning and lending. Our package of stories looks at how government is trying to insert itself into these arenas.

An unusual upscale, high-rise apartment building in downtown Milwaukee that will offer a blend of affordable and market-rate units has some real estate developers concerned about the emergence of an unlikely new competitor in the luxury housing market: the Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee.

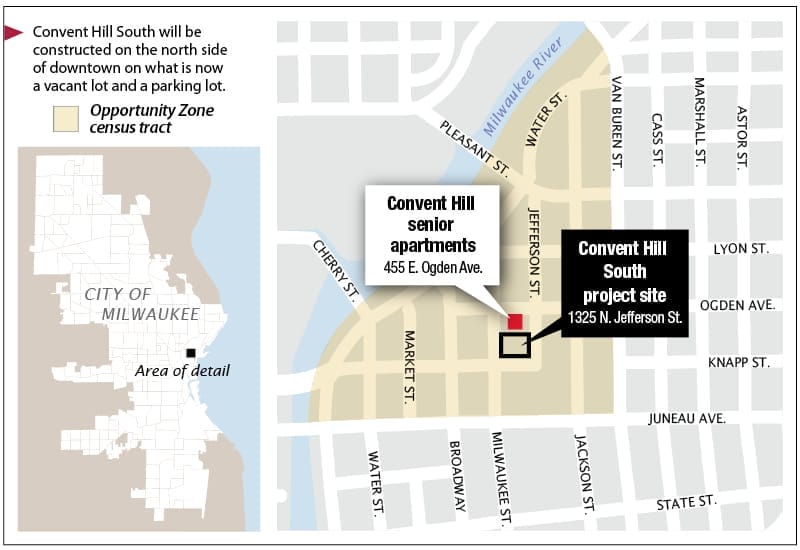

Tentatively known as Convent Hill South, the $150 million, 32-story development — slated for construction on the north side of downtown — is a hot topic among developers for two primary reasons.

First, the developer is the City of Milwaukee via Travaux Inc., a nonprofit development arm of the Housing Authority. Second, the project will employ a concept called mixed-income housing, in which some units will command the going market rate for rent, while the rest will be available to low-income earners at below-market rates.

Neither the percentage of units that will be affordable vs. market-rate or rental rates have been finalized, although it’s likely that the majority will be market-rate apartments. “It all depends on the financing and on what the market is demanding as well,” says Scott Simon, Travaux’s vice president of business development.

The handful of developers who agreed to talk to the Badger Institute about the project emphasized that they support the project’s goal of increasing the availability of affordable downtown housing. They also support the concept of people with diverse income levels living side by side.

“There’s nothing wrong with blended housing,” says Stewart Wangard, owner of Wangard Properties. “It’s something we should encourage so we have inclusion and diversity, including income levels. It’s all a part of creating a strong fabric in a neighborhood.”

Developers have concerns

But at the same time, some developers expressed concerns about the Housing Authority’s new role as a luxury apartment developer, saying it infringes on the free market and strays from the agency’s mission of providing affordable housing.

“Solving disparities in housing in the city of Milwaukee is entirely appropriate and a good thing to do,” says Blair Williams, president of WiRED Properties. “But it’s the market-rate piece of this project that seems to be raising issues … the perspective is that the Housing Authority is becoming a competitor in the free-market development community.”

“It’s certainly a non-traditional role,” says Wangard, referring to the city acting as a developer. “The Housing Authority has an important role — to provide safe and affordable housing for as many people as possible. … But I think the Housing Authority should stay true to its mission and maximize the opportunities it has with the dollars it has to spend,” he continues.

“If its mission revolved around building luxury housing, then I’d say go for it. But there are plenty of other talented people, both in our city and coming in from other areas, that can provide that kind of housing,” Wangard says.

In response, Simon says nothing is stopping developers from building mixed-income projects themselves. The Housing Authority is still focused on its primary mission of providing affordable housing, he contends. “That is the focus of this project. It’s just focused on better affordable housing.”

“If you look at what the Housing Authority has done to create affordable housing, it’s historically skewed toward developments with 100 percent affordable units,” he explains. “But part of what we’re trying to do is create less-isolated communities and give residents the opportunity to bootstrap themselves.

“This concept has been gaining traction nationwide over the last 20 years,” Simon adds. “It’s new to Milwaukee but not to the rest of the nation.”

Moreover, the market-rate units eventually could generate income that can help fund other Housing Authority efforts, he says.

More competition

The Badger Institute contacted nearly 20 developers to ask what they thought about the city entering the market for luxury housing. Most did not respond or opted to only talk off the record, citing concerns that criticizing the city could jeopardize future development proposals. But most of those interviewed agreed that the project is a hot-button topic among Milwaukee developers.

The Housing Authority’s entry into the high-end housing arena could make it more difficult for developers to pursue future downtown projects, Williams says. That’s particularly true as the local market for high-rise luxury apartments downtown appears to be reaching a saturation point after years of strong activity.

“This just gives the development community pause because it upsets the understood roles in an established market,” he explains. “It’s inherently disruptive to the way the real estate market in Milwaukee has come to understand the playing field.”

The city’s interest in building high-end housing, even if blended with affordable units, could come at the expense of private-sector developers who now may find it more difficult to obtain funding for their projects, Williams says.

Simon disputes that notion, noting that all developers — whether in the public or private sector — “play with the same set of rules” and have access to the same kinds of financing.

A unique approach

Josh Jeffers, president and CEO of J. Jeffers & Co., says he was surprised when he first heard about Convent Hill South, noting that it’s a “pretty outside-the-box approach.”

While Jeffers concedes to having mixed feelings about it, he ultimately is optimistic that it’s a proactive step toward providing high-quality, affordable housing downtown.

Jeffers also disputes the notion that the Housing Authority somehow is competing with private-sector developers of upscale housing projects. Why? Because as a blended-income development, Convent Hill South is a hybrid that private developers typically don’t build anyway.

Developer Kalan Haywood, owner of the Haywood Group, also had a mixed reaction to the project, especially since about half of the projects his company builds are affordable housing developments.

“Looking at it from a developer’s standpoint, yes, there’s another developer in your space,” he says. “On the other hand, competition is good — competition drives the best deals. And any time you can drive a good, quality housing project downtown … and draw in potential residents who otherwise wouldn’t live there, it’s a good thing.”

Haywood says he would’ve preferred to see Travaux ask local developers to partner in the Convent Hill South project. Simon hints that such partnerships might be feasible on future projects.

No subsidies sought

Announced last April and approved by the Milwaukee Common Council without discussion in early July, Convent Hill South (so named because a convent once occupied the land) is a first-of-its-kind project in the city.

It represents a decidedly different take on affordable housing — a rejection of the decades-long, failed approach to affordable housing, which essentially warehoused poor people in isolated developments, promoting racial and economic segregation.

The building will stand on a 1.4-acre parcel at 1325 N. Jefferson St. on what now is a vacant lot and a parking lot, both formerly occupied by another Housing Authority building that was demolished more than a decade ago.

The high-rise will be located on the same block as — and will stand adjacent to — the Housing Authority’s nine-story Convent Hill apartment building for low-income seniors at 455 E. Ogden Ave. The block is bounded by North Milwaukee Street, East Knapp Street, East Ogden Avenue and North Jefferson Street.

Designed by Korb + Associates Architects, the building will include up to 350 apartments. The tower will rise from a five-story base that will feature 43,000 square feet of office space, a 425-space parking ramp (including spaces for Convent Hill residents), a swimming pool and a fitness center. The top of the five-story building will be used as a large patio for residents.

Most of the apartments will be one- or two-bedroom units, ranging in size from 700 to 1,000 square feet. If everything falls into place, construction could start next year and finish in early 2022, Simon says.

Funding not yet finalized

Funding sources for the project remain undetermined, but Simon emphasizes that unlike many developers that seek state or local financial assistance, Travaux’s goal is to eschew sources such as tax incremental financing and low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC).

In the latter, private investors receive a federal income-tax credit in exchange for investing in affordable housing projects. But if developers use federal programs such as LIHTC, they’re subject to procurement and hiring requirements, such as prevailing-wage standards, that drive up project costs, Simon says.

“Our goal is to avoid city, state and federal assistance if at all possible,” he says. “Instead, we’re aiming for market-rate financing.”

Williams questions the feasibility of that goal, especially since the affordable units will not generate as much rent as the market-rate units, leaving a funding gap.

“I’m very Missouri on all this, as in ‘Show me,’” he says. “I’d love to learn how to do it. If they can build this building without (government) subsidies, more power to them. Then they should go out and build all the affordable housing they can.”

Simon points out that the site is located within a so-called Opportunity Zone, created by Congress as part of the 2017 overhaul of the federal tax code. Developers that build in Opportunity Zones receive tax breaks for investing in economically distressed neighborhoods.

“Being in an Opportunity Zone allows us to put additional equity in the project,” Simon explains. “We issue Opportunity Zone (tax) credits, and institutional or high-end investors buy them on the secondary market. Then we use the funds to pay for part of the project.”

Low-rise buildings more economical

Wangard, Williams and other developers question why the Housing Authority wants to build a high-rise rather than a more economical low-rise structure.

“You can build more housing units with the same amount of money if you build low-rise units,” Wangard says. “You pay a substantial premium per unit — 20 to 30 percent higher — when you build a high-rise building.”

“If you look at the efficiency of dollars spent, luxury towers are substantively more expensive than three- to five-story developments,” Williams adds. “The most market-efficient form of housing is a mid-rise, stick-frame apartment building. Affordable housing is a super-important thing, but I question whether creating this form of affordable housing is a super-important thing and whether there’s a more cost-effective way to fill that affordable-housing gap.”

Jeffers echoes their concerns. “It’s great to see some innovative, forward-thinking problem-solving to supply more affordable rental housing,” he notes.

“But on the other hand, I’m surprised to see that the first attempt has more in common with the Couture,” Jeffers says, referring to the $122 million, 44-story luxury apartment building slated for Milwaukee’s lakefront but long-delayed due to financing issues.

While Simon agrees that high-rise developments are more expensive to build, there’s an upside: The building’s valuation will be exponentially higher than a low-rise, which will benefit the city if it’s ever sold. “We’re trying to make the best business decisions possible — operate the Housing Authority as if it were a business,” Simon says.

Whether a mixed-income development can flourish in downtown Milwaukee is an open question. Such developments have a varied record nationwide, with success and failure dependent on factors that can differ from city to city, studies show.

As for whether another player in the market will tip the balance in terms of limiting opportunities for future upscale housing developments, only time will tell.

“No one knows which one project will be too many,” Williams points out. “But we do know that each one pushes us closer to that edge.”

Ken Wysocky of Whitefish Bay is a freelance journalist and editor.

Related stories:

► A Housing Authority subsidiary with a social mission

► Opportunity Zones stray from original intent

► The perils of state-run retirement plans

► No need for state-run student loan refinancing